Hui 2007 Joop Service

-

Upload

moeshfieq-williams -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of Hui 2007 Joop Service

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 1/22

The effects of service climate and the effectiveleadership behaviour of supervisors on frontlineemployee service quality: A multi-level analysis

C. Harry Hui 1 *, Warren C. K. Chiu 2 , Philip L. H. Yu3 , Kevin Cheng4

and Herman H. M. Tse 5

1 Department of Psychology, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong2 Department of Management and Marketing, Polytechnic University of Hong Kong,Hong Kong

3

Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science, University of Hong Kong,Hong Kong

4 Department of Politics and Sociology, Lingnan University, Hong Kong5 UQ Business School, University of Queensland, Australia

A supervisor’s behaviour may not be the only factor that determines the performanceof team members (Kerr & Jermier, 1978). Taking this postulation as a basis, weformulated a model to describe how service climate moderates the effects of theleadership behaviour of supervisors. When the organization and working environmentare not conducive to providing a good service to colleagues and customers, thesupervisor’s leadership behaviour makes an important difference. However, when theservice climate is good, a supervisor’s leadership behaviour makes no substantial

difference. This hypothesis was supported in an examination of the service quality of 511 frontline service providers as sampled from 55 work groups in 6 serviceorganizations. The employee service quality was low when both the service climate andthe supervisor’s leadership behaviour were lacking. However, when the service climatewas unfavourable, effective leadership behaviour played a compensatory role inmaintaining performance standards towards external customers. When the leadershipwas ineffective, a favourable service climate nullied the negative effect on servicequality to internal customers.

In today’s economy, the success of a business largely depends on the quality of serviceprovided to its customers (Berry, 1995; Gutek, 1995; Zeithaml & Bitner, 1996). Sasser and Arbeit (1976) distinguished between the service that is provided to internal andexternal customers, and argued that both are equally important. Quality service to

* Correspondence should be addressed to C. Harry Hui, Department of Psychology, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam,Hong Kong (e-mail: [email protected]).

TheBritishPsychologicalSociety

151

Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology (2007), 80, 151–172q 2007 The British Psychological Society

www.bpsjournals.co.uk

DOI:10.1348/096317905X89391

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 2/22

internal customers results in empowered and happy colleagues who are likely to carry out their own work more effectively (Azzolini & Shillaber, 1993). Quality service toexternal customers brings customer satisfaction and loyalty (Rogelberg, Barnes-Farrell,& Creamer, 1999), which will in turn result in repeat business (Kotler, 1999). Hurley (1998)suggests that employees with whom customers interact directly should act proactively and exercise discretion as to how they deliver service quality to satisfy or even surprisecustomers.It is thereforeimportant to understand what drivesgood service. Accordingtopast research, two antecedents to the work output of employees are service climate

(e.g. Schneider, White, & Paul, 1998) and effective leadership of direct supervisors(e.g. Bettencourt & Brown, 1997; Deluga, 1994; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, & Fetter, 1990).

Although service climate and effective leadership behaviour have been found to have asignicant impact on employee service quality, little work has been undertaken tointegrate these two conceptually related constructs in the same study. In this paper, weexamine the relative contribution of serviceclimate andeffective leadershipbehaviour toemployee service quality, and the interaction effect of these two independent variableson the outcome variable. The interaction effect is important, given the literature on thesubstitutes of leadership model (Kerr & Jermier, 1978). In addition, we note theimportance of conceptualizing service climate and effective leadership behaviour asgroup-levelvariables,andthe need to look at their inuenceonoutcome variablesbeyond

the individual level (e.g. Schneider et al. , 1998; Strutton, Pelton, & Lumpkin, 1993; Williams, Podsakoff, & Huber, 1992; Yammarino & Dubinsky, 1992, 1994). Although service climate and effective leadership behaviour can best be conceptualized as group-level variables (Ehrhart, 2004; Schneider et al. , 1998), to the best of our knowledge, nostudy has so far examined the direct and interaction effects of these two constructs atmultiple levels. This gap in the literature motivates the present study.

This study plans to make the following contributions. First, we formulate amoderating model that predicts the interaction effects between service climate andeffective leadership behaviour on employee service quality. This will contribute to anongoing discussion on the substitutes of leadership model of Kerr and Jermier (1978).Second, in response to the call for a multi-level approach, we test the model at both theindividual and group levels. Third, whereas most studies on these two potentialantecedents to employee service quality have been conducted in North America andEurope, this study considers service climate and effective leadership behaviour in aChinese society. As customer satisfaction and service quality are relatively new to many Chinese workers, data from this population will be useful for the research community indeveloping and rening theories for application beyond cultural boundaries. In thefollowing sections, we briey survey the literature on the relationships between serviceclimate, leadership behaviour and employee service quality, and then move on to adescription and test of the moderating model at the group level.

Impact of supervisor’s effective leadership behaviour on service quality The literature abounds with actions that supervisors can undertake to be effectiveleaders. These actions can be crudely organized into three clusters: task-oriented

actions (sometimes called performance or initiating structure ), people-oriented actions (sometimes called maintenance or consideration ) and ethical actions(sometimes called moral character ). The rst two have been discussed extensively by earlier researchers such as Blake and Mouton (1978), Fleishman (1967) and Misumi

152 C. Harry Hui et al.

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 3/22

(1985). Some examples of performance actions are making timely decisions, motivatingemployees, giving directions, drawing up plans and meeting deadlines. In a servicesetting, effective supervisors inuence and encourage the service behaviour of employees by setting targets for their frontline subordinates. They empower, inspire,reward and serve as role models so that their frontline subordinates understand how todeliver the best service. Maintenance actions include respecting the decisions of subordinates, resolving conicts, listening to the views of subordinates, helpingsubordinates to achieve organizational and sometimes personal goals and being

supportive when subordinates encounter work problems (e.g. Schaubroeck & Fink,1998). Moral character – or ethical leadership – has recently attracted the attention of researchers (e.g. Emler & Cook, 2001; Greenleaf, Frick, & Spears, 1996; Kanungo & Mendonca, 1996; Ling & Fang, 1995; Srivastva, 1988), and can be linked totransformational leadership (Podsakoff et al. , 1990; Turner, Barling, Epitropaki, Butcher,& Milner, 2002). Moral character includes the supervisor’s fairness (Bettencourt & Brown, 1997) and trust-building behaviour (Deluga, 1994). Good supervisors act in animpartial and non-favouring manner and do not abuse their power for personal benets.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that such effective leadership behaviour isassociated with the quality of work of subordinates in service organizations (e.g.Bettencourt & Brown, 1997; Deluga, 1994; Pillai, Schriesheim, & Williams, 1999;Podsakoff et al. , 1990; Schaubroeck & Fink, 1998). Leaders who develop a good

relationship with their subordinates will in turn inuence the level of discretionary behaviour of these subordinates (e.g. Settoon, Bennett, & Liden, 1996). In a eldexperiment, Lam and Schaubroeck (2000) found that using credible and inuentialpeople as service quality leaders could enhance the positive attitudes of bank tellerstowards service quality initiatives, which result in a more favourable customer rating of service. MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Rich (2001) found that transformational leaderscould alter the service behaviour of frontline salespeople. Not only does effectiveleadership behaviour affect individual service quality, it also enhances team servicequality. For example, supervisors’ level of ‘servant leadership’ (Greenleaf et al. , 1996) isassociated with unit-level organizational citizenship behaviour in 249 grocery storedepartments (Ehrhart, 2004). Furthermore, proactive, considerate and charismatic storemanagers have been found to signicantly improve the objective business performanceof the supermarkets that they run (Koene, Vogelaar, & Soeters, 2002). A critical mass of colleagues delivering good service has a modelling effect on others. Thus, thesupervisor’s effort in raising service quality at the team level can be multiplied in itsimpact.

Impact of service climate on service quality Service climate is derived from a consensual understanding, within a company, adepartment or a group, of how to behave in different settings and with differentcustomer populations. Borucki and Burke (1999) dened service climate in terms of employee cognitive appraisals of the organization’s attitude towards employee well-being, and the concern of members of the organization about customer well-being. Thisincludes the extent of the perception that management sets clear performance

standards, provides appropriate training and information, removes obstacles to service,assists in employee job performance and distributes rewards for good service tocustomers. A favourable service climate is associated with excellent interdepartmentalservice (Schneider et al. , 1998). Service climate is also related to the perception that

Service climate and leadership 153

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 4/22

the organization and its members assist customers, and to outcome variables such asindividual and organizational service performance (Borucki & Burke, 1999) andcustomer satisfaction with service quality (Johnson, 1996). Some data suggest that if thefavourable service climate is ‘strong’ (i.e. when employees agree on their perception of the climate), then there is a low variability in customer satisfaction. However, a weak service climate is associated with a high variability in customer satisfaction (Schneider,Salvaggio, & Subirats, 2002).

Relationship between effective leadership behaviour of supervisors and serviceclimateSome writers have conceptualized leadership behaviour as a precursor to organizationalclimate (e.g. Dickson, Smith, Grojean, & Ehrhart, 2001; Koene et al. , 2002; Litwin & Stringer, 1968) or group climate (Kivlighan & Tarrant, 2001). Kozlowski and Doherty (1989) integrated the vertical dyad linkage theory of leadership with climate perception,and showed that subordinates with whom a supervisor relates closely have a morepositive evaluation of the organizational climate than subordinates who have a poor-quality relationship with their supervisors. More recently, Schneider et al. (1998)included in their formulation of service climate the subordinates’ perception of theactions of their immediate supervisors to reward, support and expect good customer

service. Furthermore, management’s recognition and appreciation of quality serviceappears in the ‘climate for service’ scale. It should be noted, however, that although thesupervisor is a member of the organization, his or her identity is separate from that of the organization. Although there is a partial overlap between the perception of asupervisor’s behaviour and the organizational climate, a frontline supervisor does nothave the power to dictate all features contributing to the service climate. Instead, senior management cultivates and nurtures the service climate by designing the company’scompensation structure and setting policies on interdepartmental communication, themanagement of customer information, customer service policies and so forth. For thisreason, this study treats service climate and the leadership behaviour of directsupervisors as conceptually separate entities. Moreover, in our measurement, weattempt to minimize any overlapping that may confound the two constructs.

Interaction between service climate and effective leadership behaviour: A moderating modelThere is a large body of literature on the situational approach to leadership (e.g. Evans,1970; Fiedler, 1967; House, 1971). A quarter of a century ago, Kerr and Jermier (1978)theorized that theeffects of leadership canbe substituted for, neutralized or enhanced by certain contextual variables. Many researchers (e.g. Howell, Bowen, Dorfman, Kerr, & Podsakoff, 1990;Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Fetter, 1993; Podsakoff, Niehoff, MacKenzie, & Williams, 1993; Williams et al. , 1988; Yukl, 1994) have concurred that Kerr and Jermier’ssubstitutesmodelis preferable to othersituational approachesto leadership.It representsthe most comprehensive attempt to identify situational factors and explains why sometypes of leader behaviour are effective in some situations but have no effect – or even a

dysfunctional effect – in other situations (Podsakoff & MacKenzie, 1997).However, not all empirical tests have been supportive of the substitutes model(e.g. Farh, Podsakoff, & Cheng, 1987; Podsakoff & MacKenzie, 1995; Podsakoff,MacKenzie, Ahearne, & Bommer, 1995). The search for contextual variables that may

154 C. Harry Hui et al.

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 5/22

moderate the impact of leadership on criterion variables is likened by some to lookingfor ‘a needle in a haystack’ (Podsakoff et al. , 1995). This unenthusiastic view has beencontested by advocates of the substitutes model. According to Villa, Howell, Dorfman,and Daniel (2003), the failure to detect moderators in leadership research may betraceable to the theoretical nature of many of the empirical tests. Indeed, an extensivereview of the literature shows that variability in the performance of subordinates may beexplained by a number of non-leader variables, such as the professional orientation of employees, task feedback, intrinsic job satisfaction, non-routine tasks, groupcohesiveness and spatial distance among workers. When these factors are present,the competence of the leader becomes relatively unimportant.

In sum, the jury is still out on whether the substitute variables of Kerr and Jermier arein fact predictive of important criterion variables. Nevertheless, bothsides agree that thesubstitutes framework should be used to stimulate further research. For example, Jermier and Kerr (1997) stated that they had never intended to treat the substitutesframework as a closed system, and that a better specication of the conceptual domainof substitutes is long overdue. One contextual variable – shared organizational values – was proposed by Podsakoff and McKenzie (1997), and may have particular promise as amoderator. They argued that shared values or work norms can replace hierarchy or coercion, because members of a value-based organization do not need much supervision.

In this study, we focus on the employees’ shared perception that the organizationplaces much emphasis on customer well-being, and examine how such a serviceclimate, like some organizational shared values, can moderate the impact of leadershipbehaviour in a service setting. Specically, leadership effectiveness may be morestrongly correlated with subordinates’ work performance when the organizationalservice climate is not favourable than when it is favourable. We speculate that, inorganizations that do not have a positive service climate, not all employees willunderstand the need for satisfying customers or acquiring the means to do so, and nor will they perceive the organization as supporting good service. Under such circumstances, an important role of supervisors is to clarify what is expected of their subordinates in terms of customer service, and to provide the necessary coaching andmanagerial support to maintain the service quality of the work unit. This is consistent

with the ndings of Brubakk and Wilkinson (1996) that, during changes in corporateculture, managers play an important role in helping frontline employees to decode andinterpret what must be changed. In short, when the organization or the team does nothave a favourable service climate, the frontline supervisors’ effective leadershipbehaviour will play an important role helping individual service providers to understandservice values and realize the importance of customer satisfaction. When team members work individually and collectively with peers to satisfy customers, the quality of serviceprovided by the entire work team is strengthened.

There are times when leadership may not produce the intended effect. This happensin settings in which the organizational climate clearly supports, encourages, andrewards service (Martin, 2002). When there are sufcient mechanisms to guide andorchestrate employee behaviour, the immediate supervisor’s leadership behaviour is of

relatively minor importance. Furthermore, a competent supervisor who issuesdirectives that are not completely in line with the organizational values embodied inthe service culture and climate can promote confusion and dysfunction. In such asituation, Porter and Bigley (2001) predict that role ambiguity results among

Service climate and leadership 155

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 6/22

subordinates. This, in turn, depresses service quality indirectly, as Hartline and Ferrell(1996) showed in their study of hotel employees.

Hence, leadership can even backre: ‘the popular idea that low levels of motivationcan be remedied by increased transformational leadership behaviour appears to beoverly simplistic where organizations are concerned. Indeed, low levels of employeemotivation may be caused by too much transformational leadership behaviour in theorganization’ (Porter & Bigley, 2001, p. 288). Likewise, when a highly acclaimedleader’s direction does not align with what is prescribed for a well-developed service

climate, the benets of leadership effectiveness and favourable service climate may becancelled out.

We therefore hypothesize that the relationship between effective leadershipbehaviour and employee service quality will be stronger in work groups in anunfavourable service climate, and weaker or even reversed in those that operate in apositive service climate. We adopt a multi-level approach to test this hypothesis.

MethodRespondents and proceduresTo ensure the generalizability of our prospective ndings to a broad spectrum of companies in the service industry and to maximize the variability of the constructs of

interest, we sampled a variety of organizations: a telecommunications company, a retailchain, two hotels, an auto-repair company and a government department. All of theseorganizations pride themselves in their effort to satisfy customers, and some have evenmade this a part of their mission statement. The research participants were all Chinesefrontline service staff who worked in service teams of varying sizes.

A team is dened either by function or by locality. For instance, in a hotel, a team may comprise all of the staff in a restaurant, whereas in a retail organization, it may bedened by sales outlet. A team is generally led by a supervisor, to whom all teammembers report. During our negotiation with the organizations, we requested access toteams that met two conditions: the members of such teams had to have regular contact with customers, and the team members had to have more than 6 months workingexperience in that frontline position. For very large teams, we randomly selected about75% of the individuals from a name list that the company supplied. We did not requestparticipation from everyone in order to avoid unnecessary disruption to the company’sbusiness day-to-day operation.

Fifty-ve service teams (511 employees) participated in the study. They included 14teams from the telecommunications company, 11 from the retail chain, 7 from the twohotels, 13 from the auto-repair company and 10 from the government department. Theteams ranged in size from 5 to 20 members. Slightly over two-thirds had 10 or fewer members. In this sample, 61% of the participants were female, 49.5% were within the 15to 30 age bracket, and 32.8% were within the 31 to 40 age bracket.

Data collection sessions were held in groups of 5 to 20 people in either a trainingroom or a large recreation area near or at their place of work. Each session began with a researcher explaining that the aim of the study was to gain a better understanding of service workers. Although attendance was arranged by the

respective organizations, the researcher told prospective participants that they couldchoose not to take part. Participation rates ranged from 60% to 85% in the sampledteams. If the participation rate went below 50%, the researcher dropped the team tomove on to another.

156 C. Harry Hui et al.

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 7/22

The supervisors of the participants separately rated the service quality of their subordinates. Condentiality was guaranteed for both the frontline employees and their supervisors. The questionnaires that the subordinates completed were collected at theend of the session, and the questionnaires of the supervisors were collectedapproximately one week after distribution.

Although we initially secured the cooperation of 1,035 employees, only teams with veor more members whoprovided complete answers to our survey questionnaire wereincluded in our study. This was necessary because a reasonable group size was required

for a reliable estimation of the group-level variables (Bliese, Halverson, & Schriesheim,2002), which were used in the hierarchical linear modelling (HLM) analysis.

Measures

Supervisor’s effective leadership behaviour This construct was measured by aggregating the reports of subordinates about their supervisors on 15 behavioural items (see Appendix), adapted from severalquestionnaires used to measure leadership behaviour (Hui & Tan, 1999; Ling & Fang,1995; Misumi, 1985). This selection was in keeping with our earlier argument thateffective leadership behaviour comprises three aspects: task-oriented actions (or performance), people-oriented actions (or maintenance) and ethical leadership (or

moral character). Most of the items that pertained to task-oriented and people-orientedactions were adapted from the Misumi (1985) Performance-Maintenance Question- naire. The items on ethical leadership were derived from the studies of Hui and Tan(1999) and Ling and Fang (1995). A 6-point scale anchored by strongly disagree and strongly agree was used. A principal components analysis revealed only one generalfactor, which accounted for more than 59% of the total variance. The Cronbach’s alpha was .95.

Service climateSchneider (Schneider, Ashworth, Higgs, & Carr, 1996; Schneider et al. , 1998)developed four Climate for Service scales, namely, ‘global service climate’, ‘customer orientation’, ‘managerial practices’ and ‘customer feedback’. Of these, we used only the rst two subscales (16 items in total). There are three reasons for this decision.First, we needed to keep the survey questionnaire to a reasonable length to securethe cooperation of both the companies and their employees. Second, these subscalesare highly correlated with each other ( r s ¼ : 50 to .74; Schneider et al. , 1998). With ‘global service climate’ being correlated with ‘customer feedback’ at r ¼ : 63, somesubscales can clearly be omitted. Third, as there is already too much conceptual andtextual overlap between the effective leadership behaviour measure and the‘managerial practices’ subscale, to avoid confounding the effect of the former in our model, it was better to have left the latter out.

Some of the items that were included were: ‘employees’ job knowledge and skills todeliver work and service’, ‘the business does a good job keeping customers informed of changes that affect them’ and ‘top management has a plan to improve the quality of our

work and service’. There were two items from the ‘climate for service’ measure thatseem to refer to leadership (e.g. ‘the recognition and rewards employees receive for thedelivery of superior work and service’ and ‘leadership shown by management insupporting the service quality effort’). However, closer examination revealed that they

Service climate and leadership 157

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 8/22

are more related to the company’s general management practice than the behaviour of direct supervisors and thus would not confound our two research variables. A comparison of two models (one with and the other without the two items as partof the leadership behaviour measure) also conrmed this. For this reason, we decided toretain the two items in our measure.

The subsequent principal component analysis indicated a unidimensional structure.This is not surprising in view of the high correlation ( r ¼ : 74) that was rst reported by Schneider et al. (1998). The 7 items of the ‘global service climate’ subscale were rated

on a 5-point scale that ranged from poor to excellent ). However, since the items of the‘customer orientation’ subscale were anchored by strongly disagree and strongly agree , we used a 6-point format to avoid a ‘neutral’ mid-scale anchor for our Chineserespondents, who are relatively high on a central tendency response set. To give equal weighting to each item when aggregating for an overall service climate score, wetransformed the 5-point ratings into a 6-point scale by subtracting the ratings by 1 anddividing by 4. We then multiplied the ratio by 5 and added 1 to the product term. TheCronbach’s alpha was .90.

Although most of the items used in this study were validated previously, there may still be questions as to whether there are conceptual differences between organizationalservice climate and leadership behaviour. To verify this, we conducted conrmatory factor analyses on the 15 leadership and 16 service climate items, to test whether the

team members’ ratings would load on two distinct factors. Results showed that the one-factor model (CFI ¼ : 89, GFI ¼ : 83, AGFI ¼ : 81, RMSEA ¼ : 07, x 2 ð434 Þ ¼ 1 ; 404 : 361)offered a signicantly poorer t than the two-factor model (CFI ¼ : 90, GFI ¼ : 84, AGFI ¼ : 82, RMSEA ¼ : 06, x 2 ð433 Þ ¼ 1 ; 310 : 48; x

2 difference test statistic ¼ 93 : 88,df ¼ 1, p ,

: 0001). This conrms that, although related to each other, service climateand leadership behaviour are conceptually distinct.

Outcome measuresEmployee quality of customer service was operationalized by the respectivesupervisor’sratings on an Employee Service Quality Scale (Hui, Cheng, & Gan, 2003). The rstsubscale, ‘service to internal customers’, had 9 items that explored facilitative behaviour directed at internal customers. The raters reported the frequency of such actions over the previous 3 months (1 ¼ once or never ; 6 ¼ six or more times ). Sample itemsincluded ‘respond immediately to co-workers’ urgent requests’, ‘inform other teammembers about changes that might affect service quality’ and ‘voluntarily assist workersfrom other departments’. The Cronbach’s alpha was .90. The second subscale, ‘serviceto external customers’, had 7 items, and measured behaviour that was directed atexternal clients. Sample items included ‘willingly listen to customers’requests’, ‘providenon-standard service to customers’ and ‘liaise with different departments to provideservice in one service contact’. The Cronbach’s alpha was .86. For both subscales, a high score indicated high service quality. Although the two subscales are correlated ( Table 1),conrmatory factor analyses conducted using AMOS showed that the one-factor model(CFI ¼ : 73, GFI ¼ : 70, AGFI ¼ : 61, RMSEA ¼ : 14, x 2 ð119 Þ ¼ 1370 : 30) offered asignicantly poorer t than the two-factor model (CFI ¼ : 85, GFI ¼ : 83, AGFI ¼ : 76,

RMSEA ¼ : 11, x2

ð118 Þ ¼ 801 : 83; x2

difference test statistic ¼ 568 : 47, df ¼ 1, p ,: 0001). Service to internal customers and service to external customers are related

but non-identical aspects of an underlying service construct. Hence, we treated thesetwo subscales as separate outcome measures.

158 C. Harry Hui et al.

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 9/22

Hierarchical linear modelling (HLM) as a multi-level analytic techniqueHLM is a popular method for analysing data in a nested structure by constructing aseparate submodel at each of the levels in the data structure (Bryk & Raudenbush, 2002;Bryk, Raudenbush, & Congdon, 1996). It allows us to make simultaneous inferences on

the effects of variations in the independent variables at the individual level and grouplevel on the dependent variables, and the cross-level moderating effect of theindependent variables on the dependent variable at the individual level.

To understand multi-level models, it is useful to begin with a simple (single-level)regression model for employee service quality ( y ):

yi ¼ b0 þ b1 x i þ ei ;

where the subscript i represents the i th employee and x i is the employee rating of thesupervisor’s leadership behaviour centred about the supervisor mean. The modelassumes that the differences between supervisors are constant across the range of employee service quality scores. We can think of the regression line as a supervisor-levelsummary of this relationship, which may vary from supervisor to supervisor. This kindof variation is known as group-level variation. To account for both individual-level andgroup-level variation, we consider the following multi-level model with randomintercepts:

Individual level : yij ¼ b0 j þ b1 x ij þ eij ;

Grouplevel : b0 j ¼ c 0 þ c 1 gx j þ c 2 gc j þ c 3 gx j £ gc j þ u j ;

where the subscript i indicates the employee and the subscript j indicates thesupervisor, and gx j represents the aggregated ratings of the supervisor’s effectiveleadership behaviour, gc j represents service climate and gx j £ gc j represents theinteraction between the two. To see all of the predictors that are implied in the two-levelmodel, we substituted the group-level model into the individual-level model, which resulted in a single equation model:

yij ¼ ðc 0 þ c 1 gx j þ c 2 gc j þ c 3 gx j £ gc j þ u j Þ þ b1 x ij þ eij :

At the individual level, a linear model was built to predict employee service quality based on the individual ratings of the supervisor’s effective leadership behaviour x ij .

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and correlations at individual level and group level a

Individuallevel Group level

Variables Mean SD Mean SD 1 2 3 4

1. Service quality to internal customers 3.00 1.32 2.98 0.89 .90 .68*** 2 .08 .022. Service quality to external customers 3.57 1.32 3.45 1.11 .60*** .86 .09 .05

3. Effective leadership behaviour 4.01 0.92 4.03 0.41 .09* .09* .95 .48***4. Service climate 3.77 0.81 3.79 0.43 .08 .04 .53*** .90

The theoretical range of all ratings is 1–6; the Cronbach’s alphas are presented on the diagonal;elements below the diagonal are correlations between constructs at individual level; elements abovethe diagonal are correlations at group level.*p ,

: 05; **p ,: 01; ***p ,

: 001a N ¼ 511 at the individual level and N ¼ 55 at the group level

Service climate and leadership 159

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 10/22

As x ij is centred about the supervisor mean, each intercept parameter b0 j that wasobtained from the individual level indicated the corresponding supervisor’s mean ratingof the service quality of their subordinates. At the group level, another linear model wasbuilt to relate these intercept parameters and the aggregated ratings of the supervisor’seffective leadership behaviour and service climate. The model had two residuals: theindividual level residual eij , which measured the difference between actual employeeservice quality and expected service quality based on the individual-level model, and thegroup-level residual u j , which measured the difference between a supervisor’s meanrating of the service quality of subordinates and the supervisor’s expected servicequality rating based on the group-level model.

ResultsPreliminary analysesThe employees in the sample were slightly older ( t ¼ 22 : 55, p ,

: 001) and moreexperienced in the industry ( t ¼ 33 : 78, p ,

: 001) than those that were not selected for the study. They had also been employed longer in the organization ( t ¼ 68 : 43, p ,

: 001).Despite this, the two groups did not differ in their rating of their supervisor’s leadershipbehaviour( t ¼ 1 : 10, ns ) and service climate ( t ¼ 0 : 02, ns ), nor did they differ in quality of service for internal ( t ¼ 1 : 64, ns ) and external customers ( t ¼ 2 1 : 04, ns ).

All subsequent analyses were performed on the sample of 511 employees. Table 1shows the means, standard deviations and correlations of the variables at the individualand group levels.

At both levels, the quality of service that was delivered to internal customers isassociated with that delivered to external customers, but not to service climate. Theratings of service climate and effective leadership behaviour are also correlated. Servicequality is signicantly related to effective leadership behaviour at the individual level,but not at the group level. To account for the impact of different types of business andorganizational structures on service quality, we controlled for organization type (i.e.public vs. for-prot) in our analyses. After introducing the multi-level structure to themodel, we found the organization type effect to be signicant for service quality toexternal customers, but not for service quality to internal customers.

Data aggregation: Analysis of within-group consistency and between-groupdifferencesBoth h

2 and intra-class correlation (ICC(1)) as computed through a random interceptsmodel indicated the proportion of total variance between teams (Bliese, 2000; Bryk & Raudenbush, 2002). According to Bliese, ICC(1) values are typically under .20 and areusually smaller than the corresponding h

2 values. In our case, the ICC(1) and h2 are .26

(range ¼ : 06– : 50) and .20, respectively, for service climate, and .14 (range ¼ 2: 02– : 33)

and .22, respectively, for effective leadership behaviour. ICC(2) was used to estimate thereliability of the mean values that we obtained from aggregation. The ICC(2) values for service climate and effective leadership behaviour are .51 and .58, respectively. There is

thus a substantial variance in service climate and effective leadership behaviour betweenteams.Themean r wg values ( James, Demaree, & Wolf, 1993) for the two group-levelvariables

(service climate and effective leadership behaviour) are .62 ( SD ¼ 0 : 24) and .80

160 C. Harry Hui et al.

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 11/22

( SD ¼ 0 : 11), respectively. Both values are higher than the .60 cut off recommended by James (1982), and indicative of adequate agreement among the team members.

Taken together, the r wg and ICC values reveal an overall picture of between-teamdifference and some within-team similarities. The broad range of agreement valuesreects reality that, in certain teams and for various reasons, members do not alwaysconcur in their perceptions. Although somewhat below the recommended benchmark,ICC (1) ¼ .12 (James, 1982) and ICC (2) ¼ .60 (Glick, 1985), the ICC estimates for service climate are above those that are reported by Schneider et al. (1998), with ICC

(1) ¼ .09 and ICC (2) ¼ .47. As Schneider et al. were still able to aggregate for groupdata and obtain meaningful analytic results at that level of agreement, given our presentICC estimates, aggregation is still a reasonable method forestimating the two group-level variables of service climate and effective leadership behaviour.

Hierarchical regression analysis We conducted a two-level hierarchical regression analysis to predict service quality for internal customers and another to predict service quality for external customers. Theproportion of variance in service quality for internal customers between supervisors is36.4%, and the proportion of variance in service quality to external customers betweensupervisors is 60.7%. This means that around 36% to 61% of the variation occurs over the

employees nested within the supervisors. A signicant chi-squared statistic for the error variance that is estimated at the group level indicates that there is systematic variance inthe intercept across supervisors (residual variance for service quality to internalcustomers ¼ 0 : 64, p ,

: 0001; residual variance for service quality to externalcustomers ¼ 1 : 13, p ,

: 0001). Table s 2 and 3 contain the regression coefcients of the hierarchical regression analyses.

Three multi-level regression models were considered, with the effects of organization type, team size and effective leadership behaviour being controlled for atthe individual level. Model 1 depicts the impact of effective leadership behaviour only,and is supported at the individual-level for both dependent variables. Model 2 includesboth predictors at the individual and group levels. However, the addition of this serviceclimate variable did not improve the prediction of either dependent variable at either level. Model 3 differs from Model 2 in that it includes the interaction term at both theindividual and group levels, although only the interaction term at the group-level issignicant for both dependent variables. Testing Models 2 and 3 revealed that thepsychological service climate at the individual-level did not have a signicant effect. Thisis probably because the construct is either non-existent or because there is too much measurement error. If the latter is true, then there is a reason for aggregating the dataand for examining the effects at the group-level only. In fact, the removal of thepsychological service climate at the individual level yielded similar results, which are notshown here due to space limitations.

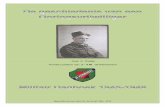

To interpret the interaction effect on service quality in Model 3, we considered twolevels of effective leadership behaviour and two levels of service climate by taking thestandard deviation from its own mean and forming high and low levels of effectiveleadership behaviour and of favourable service climate. Figure 1 shows the estimated

quality of service to internal and external customers for these four combinations. When the service climate is poor, a supervisor who displays effective leadershipbehaviour enhances employee service quality. A simple slope test (Aiken & West, 1991)showed that this effect is especially pronounced for service to external customers

Service climate and leadership 161

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 12/22

T a

b l e 2

. T w o - l e v e l

h i e r a r c h i c a l r e g r e s s i o n a n a l y s i s p r e d i c t i n g s e r v i c e q u a l i t y t o i n t e r n a l c u s t o m e r s a

C o e f c i e n t s

L e v e l

V a r i a b l e

M o d e l 1

M o d e l 2

M o d e l 3

S t a n d a r d i z e d c o e f c i e n t s

o f M o d e l 3

I n d i v i d u a l

P u b l i c v e r s u s f o r - p r o t o r g a n i z a t i o n

b

2 . 2

3 ( . 1 6 )

2 . 2

5 ( . 1 9 )

2 . 2

2 ( . 1 9 )

–

G r o u p s i z e

. 0 1 ( . 0 4 )

. 0 1 ( . 0 4 )

2 . 0

0 ( . 0 4 )

–

E f f e c t i v e l e a d e r s h i p b e h a v i o u r

. 2 0 ( . 0 5 ) * * *

. 1 9 ( . 0 7 ) * *

. 1 9 ( . 0 7 ) * *

. 1 6

P s y c h o l o g i c a l s e r v i c e c l i m a t e

. 0 2 ( . 0 7 )

. 0 2 ( . 0 7 )

. 0 1

E f f e c t i v e l e a d e r s h i p b e h a v i o u r £ P s y c h o l o g i c a l s e r v i c e

c l i m a t e

2 . 0

5 ( . 0 7 )

2 . 0

3

G r o u p

I n t e r c e p t

2 . 8

4 ( . 1 6 ) * * *

2 . 8

3 ( . 1 8 ) * * *

2 . 9

3 ( . 1 8 ) * * *

–

E f f e c t i v e l e a d e r s h i p b e h a v i o u r

2 . 2

1 ( . 3 2 )

2 . 1

8 ( . 3 5 )

2 . 2

1 ( . 2 6 )

2 . 0

9

S e r v i c e c l i m a t e

2 . 0

8 ( . 3 6 )

2 . 0

4 ( . 3 6 )

2 . 0

2

E f f e c t i v e l e a d e r s h i p b e h a v i o u r £ S e r v i c e c l i m a t e

2 . 9

4 ( . 3 8 ) *

2 . 2

3

P u b l i c o r g a n i z a t i o n ( c o d e d 1 ) : a g o v e r n m e n t d e p a r t m e n t .

F o r - p r o t o r g a n i z a t i o n ( c o d e d 2

1 ) : h o t e l s , a t e l e c o

m m u n i c a t i o n s c o m p a n y , a n a u t o - r e p

a i r c o m p a n y a n d a r e t a i l c h a i n

.

* p

,

: 0 5 ; * * p

,

: 0 1 ;

* * * p

, : 0

0 1

a S t a n d a r d e r r o r s a r e i n p a r e n t h e s e s .

b T h i s c o n t r o l v a r i a b l e c a n b e e n t e r e d a t e i t h e r t h e i n d i v i d u a l l e v e l o r t h e g r o u p l e v e l w i t h o u t c h a n g i n g t h e v a l u e o f t h e p a r a m e t e r e s t i m a t e s .

162 C. Harry Hui et al.

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 13/22

T a

b l e 3

. T w o - l e v e l

h i e r a r c h i c a l r e g r e s s i o n a n a l y s i s p r e d i c t i n g s e r v i c e q u a l i t y t o e x t e r n a l c u s t o m e r s a

C o e f c i e n t s

L e v e l

V a r i a b l e

M o d e l 1

M o d e l 2

M o d e l 3

S t a n d a r d i z e d c o e f c i e n t s

o f M o d e l 3

I n d i v i d u a l

P u b l i c v e r s u s f o r - p r o t o r g a n i z a t i o n

b

2 . 3

6 ( . 1 8 ) *

2 . 4

5 ( . 2 0 ) *

2 . 4

2 ( . 2 1 )

–

G r o u p s i z e

. 1 0 ( . 0 3 ) * *

. 0 9 ( . 0 3 ) * *

. 0 8 ( . 0 3 ) *

–

E f f e c t i v e l e a d e r s h i p b e h a v i o u r

. 1 2 ( . 0 4 ) * *

. 1 6 ( . 0 5 ) * *

. 1 5 ( . 0 5 ) * *

. 1 2

P s y c h o l o g i c a l s e r v i c e c l i m a t e

2 . 0

7 ( . 0 6 )

2 . 0

7 ( . 0 6 )

2 . 0

5

E f f e c t i v e l e a d e r s h i p b e h a v i o u r £ P s y c h o l o g i c a l s e r v i c e

c l i m a t e

2 . 0

5 ( . 0 7 )

2 . 0

3

G r o u p

I n t e r c e p t

3 . 3

5 ( . 1 8 ) * * *

3 . 2

9 ( . 2 0 ) * * *

3 . 3

9 ( . 2 1 ) * * *

–

E f f e c t i v e l e a d e r s h i p b e h a v i o u r

. 3 0 ( . 3 4 )

. 4 7 ( . 3 8 )

. 4 2 ( . 3 3 )

. 1 7

S e r v i c e c l i m a t e

2 . 3

9 ( . 4 5 )

2 . 3

4 ( . 4 4 )

2 . 1

5

E f f e c t i v e l e a d e r s h i p b e h a v i o u r £ S e r v i c e c l i m a t e

2 . 9

8 ( . 4 4 ) *

2 . 2

4

P u b l i c o r g a n i z a t i o n ( c o d e d 1 ) : a g o v e r n m e n t d e p a r t m e n t .

F o r - p r o t o r g a n i z a t i o n ( c o d e d 2

1 ) : h o t e l s , a t e l e c o

m m u n i c a t i o n s c o m p a n y , a n a u t o - r e p

a i r c o m p a n y a n d a r e t a i l c h a i n

.

* p

,

: 0 5 ; * * p

,

: 0 1 ;

* * * p

, : 0

0 1

a S t a n d a r d e r r o r s a r e i n p a r e n t h e s e s .

b T h i s c o n t r o l v a r i a b l e c a n b e e n t e r e d a t e i t h e r t h e i n d i v i d u a l l e v e l o r t h e g r o u p l e v e l , w i t h o u t c h a n g i n g t h e v a l u e o f t h e p a r a m e t e r e s t i m a t e s .

Service climate and leadership 163

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 14/22

(slope ¼ : 85, t ¼ 3 : 11, p ,: 001), although the slope is not signicantly different from

zero for service to internal customers. When the service climate is positive, thesupervisor’s effective leadership behaviour does not make a difference in the service of subordinates to external customers, but surprisingly is associated with low servicequality to internal customers (slope ¼ 2

: 60, t ¼ 2 2 : 02, p ,: 05).

DiscussionThis study aimed to examine how the two key variables of effective leadershipbehaviour and service climate are related to the work performance of frontlineemployees. We hypothesized that the relationship between supervisors’ effectiveleadership behaviour and subordinates’ service quality would be more prominent in anunfavourable than in a favourable service climate. The results provide preliminary support to our prediction of an interaction effect. In an unfavourable service climate,compared with teams led by less effective supervisors, teams led by effectivesupervisors delivered better service (especially to external customers). In a favourableservice climate, however, effective leadership behaviour does not seem to enhance theservice that subordinates provide to external customers. It may even be negatively related to the quality of service provided to internal customers. In the followingparagraphs, we interpret the interaction effects, speculate on why combining effectiveleadership behaviour with a favourable service climate does not always lead to better team outcomes, discuss why neither variable has a main effect on team outcomes anddescribe the limitations of this study.

Interaction effect on quality of service to external customersIn the present study, teams led by effective supervisors and having a favourable serviceclimate did not receive the highest ratings on quality of service to external customers.

The rst explanation is that supervisors (also the raters) in such teams had very high performance expectations for their subordinates, and were therefore harsh when ratingtheir subordinates’ service quality. Second, as we pointed out in the Introduction, a co-occurrence of a good leader and a favourable service climate may lead to role conict;

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Ineffective leadershipbehaviour

Effective leadershipbehaviour

S e r v

i c e q u a

l i t y t o i n t e r n a

l c u s

t o m e r s

Unfavourable service climateFavourable service climate

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Ineffective leadershipbehaviour

Effective leadershipbehaviour

S e r v

i c e q u a

l i t y t o e x

t e r n a

l c u s

t o m e r s

Unfavourable service climateFavourable service climate

Figure 1. Subordinates’ service quality as a function of service climate and supervisors’ effectiveleadership behaviour.

164 C. Harry Hui et al.

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 15/22

that is, when the leader points at a direction different from that of the company. Third,perhaps a favourable service climate does not alter the level of service very much.Instead, it merely maintains a certain level of service critical for the organization tosurvive, such that the service quality is consistent even when the team is under thesupervision of someone not very effective in leadership. However, an unfavourableclimate becomes a backdrop for competent leaders to demonstrate their skills andcharisma in full strength, and to motivate their subordinates into productive activities.Furthermore, when organizational service climate is not as favourable, employees may

not know exactly what their performance goals should be. Those who are willing to work extra hard could be prompted by a good leader to display more service behaviour.This effect was evident in some dot-coms that were starting up during the 1990s. Whilethose companies did not have in place a perfect set of practices and policies (which area component of favourable service climate), at the inspiration of their visionary bossesemployees were still willing to work extra hours to serve their customers.

Of course, we would not recommend that management should keep service climateunfavourable in order that frontline employees have high external service quality.Maintaining an unfavourable service climate would put businesses at risk. This isbecause teams that have poor service climate may deliver no service at all, if thesupervisor is a very ineffective leader, as can be visualized by extrapolating the left-handbottom part of Figure 1. Unfavourable service climate is a liability to any organization,

while a favourable climate provides a buffer against poor leadership. In fact, strongmanagement should be introduced and competent managers selected for places whereservice climate is poor.

Interaction effect on quality of service to internal customersThe fact that employees deliver a better service to internal customers when their supervisors are ineffective leaders than when their supervisors are effective in afavourable service climate is not unexplainable. This phenomenon is consistent with thesuggestion of Netemeyer, Boles, Mckee, and McMurrian (1997) that colleagues help oneanother to enhance customer relations when supervisors cannot provide timely assistance and advice. As our data show, such mutual assistance when supervisors areineffective exists only in a service climate that provides members with structures,standards and implicit rules on satisfying customers. A positive organizational climatemay have cultivated a collegial spirit and motivated employees to make up for any shortcomings that are due to supervisors not functioning as they should. In the absenceof such a climate, however, members are unlikely to become good organizationalcitizens.

Ironically, when the service climate is favourable and leadership is effective, thequality of service may also be low. Teams with both ‘desirable’ conditions recorded alower than expected performance. This nding is nevertheless in line with that which others have reported in the literature. For example, in their study of over 100 teams inthe pharmaceutical industry, Gibson and Vermeulen (2003) found that when a team‘already has an impetus to [perform], a performance management push by its : : : .leader may be superuous’ (p. 214). This set of ndings corroborates the postulation

that leaders are not needed under certain conditions (De Vries, Roe, & Taillieu, 2002;Kerr & Jermier, 1978). Although this pattern of interaction conrms the predictions of the substitutes

model, it challenges the deep-seated belief that an effective leader and a favourable

Service climate and leadership 165

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 16/22

climate should be additive in their positive impact on employees’ service to their colleagues and peers. For this somewhat novel nding, we offer further theoretical andanalytical discourse.

First, a highly effective (and therefore possibly persuasive) supervisor and afavourable service climate together may be confusing to the subordinates, if their directions are not consistent with each other. This proposition deserves further investigation in future research.

Second, when the supervisor and the service climate are working in alignment, the

result would probably be an emphasis on serving external customers over the internalones. This is because few organizations explicitly enforce and reward extra-rolebehaviour (Organ, 1988, 1997). Therefore, working beyond their prescribed duties toassist their colleagues is entirely the employees’discretion. These discretionary acts willbe less frequent when two conditions coexist: a positive service climate that directs theattention of employees to their tasks, which for our participants working in thefrontline, largely involves serving external customers, and a supervisor who effectively reinforce this idea. After all, management assesses and rewards frontline employeesprimarily on the basis of how well they serve external customers, but not internalcustomers, even though it is important to do both.

Third, as in the case of rating of service to external customers, this rating could beharsh among effective supervisors and less so among the less effective ones. The

emphasis of service in the organization or team may also elevate the expectations, thusresulting in a lower rating of employees who were in teams where the service climate was favourable and the leader was highly competent. The above explanations should betaken with a grain of salt, because although the interaction effect was signicant, neither slope was signicantly different from zero.

Absence of group-level main effectsIn this study, effective leadership behaviour predicted employee service quality only atthe individual level but not at the group level. Two explanations can be offered for thisapparent inconsistency. First, the correlation at the individual level may merely be aresult of mutual appreciation between the supervisor and the subordinate spilling over into the subordinate ratings of leadership behaviour and the supervisor ratings of service quality. Second, individual ratings of the leadership behaviour of supervisorsreect the supervisor’s actions towards the subordinate concerned, and therefore have astronger impact on the subordinate’s work performance than an abstract measure of leadership behaviour that is displayed towards a range of subordinates and aggregatedfrom ratings provided by these subordinates.

We did not nd any main effect of service climate. A positive service climate does notalways result in the favourable evaluation of the work performance of service providers. Although one may attribute this to the fact that we did not measure service climate with the ‘customer feedback’ subscale, we note that Schneider et al. (2002) found no maineffect for service climate on customer perception either, despite using the full scale. Webelieve that service climate is more ‘remote’ and intangible than leadership behaviour from the subordinates’ perspective, and thus is less potent. Another explanation is that,

although there may be a link between service climate and individual employee serviceperformance in theory, the operation of a myriad other factors and moderators may havemasked the relationship. Unfortunately, many of these moderators are as yet unknown.This study, which sampled a variety of organizations, takes a step towards understanding

166 C. Harry Hui et al.

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 17/22

the boundary conditions that surround the effect of service climate. As we have shown,a positive service climate may well go some way towards preserving service quality when leadership is mediocre, but paradoxically may not help when the supervisor displays behaviour that is regarded as effective.

One further explanation for the lack of effect of service climate pertains tomethodology. In the teams in which good service was accorded a high value,supervisors might have been conditioned to use an unduly high standard when they rated the performance of their subordinates. The net result of this stringency bias would

then be a depression of performance ratings in the teams that operated within afavourable service climate. However, although this is a possible explanation, futureresearch should continue to search for substantive explanations for this phenomenon.

At a conceptual level, these ndings cast doubt on the robustness of a direct causallink between leadership behaviour and organizational service climate on the one handand employee service quality on the other. On the contrary, they provide support for thesubstitutes model that is discussed at the beginning of this article. More research isneeded to replicate the present ndings and to identify other boundary conditions of these determinants.

Limitations, future research and practical implications

Like any study, this one is not without limitations. We have slightly over-sampled older and more experienced employees, and many of the teams that were sampled had fewer than 10 members and some as few as 5. This sampling procedure presented twoproblems. First, the data that were aggregated from a small group might have beencorrupted by one or two outliers, which would have resulted in unreliable ndings.Second, the generalizability of our ndings to larger teams may be restricted.Fortunately, subsequent correlation analyses showed no systematic relationshipbetween team size and any of the major variables except service quality to externalcustomers ( r ¼ : 26, p ,

: 001). Furthermore, as team size was controlled in all of theregression analyses, we can be condent that its effect on our ndings was minimal. Allthings considered, our ndings are probably generalizable to working environments with small and medium-sized service teams that are staffed by ‘seasoned’ customer service personnel.

Another limitation of the present study is that employees’ service quality wasassessed by supervisors only. While the use of supervisory rating is already animprovement over the use of self-rating as in most early organizational citizenshipbehaviour studies, supervisors’ rating stringency could partially account for theobservation that effective leadership did not bring good performance ratings when service climate is excellent. Future research should therefore examine theinteraction effect with other rating sources, such as using customers’ and possibly 360 8

assessment.This study has several practical implications. In today’s economy, the bottom line of

commercial organizations depends on how service is delivered at the frontline. To excelin the service industry, supervisors are taught leadership skills and managementconsultants are brought in to help cultivate a service climate. Sometimes these initiatives

are uncoordinated, with supervisors and management consultants emphasizing their own interest domain. For example, leadership workshops may inspire supervisors to beattentive to the needs of their subordinates and to encourage them to innovate, whereasmanagement consultants may implement standardized ways in which to serve

Service climate and leadership 167

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 18/22

customers better. These two driving forces are not necessarily opposed to oneanother, but organizations should be aware of any potential incompatibility or redundancy.

In sum, the present study is probably one of the few to suggest that a good supervisor and a positive service climate may work against one another. Practitioners are thusadvised to assess how these two performance drivers can best be combined andmanaged in their own organizations. However, readers are reminded that results anddiscussions of this study, while intriguing, are exploratory and need to be replicated in

future research.

AcknowledgementsThis research as partially supported by a research grant (Project B-Q416) from theHong Kong Polytechnic University. All ve authors contributed equally to the research and writing of this paper. We wish to thank Fleur Sequeira and David Wilmshurst for comments on anearlier draft.

References Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions .

London: Sage. Azzolini, M., & Shillaber, J. (1993). International service quality: Winning from the inside out.

Quality Progress , 26 , 75–78.Berry, L. L. (1995). Relationship marketing of service – Growing interest, emerging perspectives.

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , 23 , 236–245.Bettencourt, L. A., & Brown, S. W. (1997). Contact employees: Relationships among

workplace fairness, job satisfaction and prosocial service behaviors. Journal of Retailing ,73 , 39–61.

Blake, R. R., & Mouton, J. S. (1978). The new managerial grid . Houston, TX: Gulf.Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence and reliability: Implications for

data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory,research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions( pp. 351–424). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bliese, P. D., Halverson, R. R., & Schriesheim, C. A. (2002). Benchmarking multilevel methods in

leadership: The articles, the model and the data set. Leadership Quarterly , 13 , 3–14.Borucki, C. C., & Burke, M. J. (1999). An examination of service-related antecedents to retail storeperformance. Journal of Organizational Behavior , 20 , 943–962.

Brubakk, B., & Wilkinson, A. (1996). Agents of change? Bank managers and the management of corporate culture change. International Journal of Service Industry Management , 7 , 21–43.

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and dataanalysis methods (2/e) . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bryk, A. S., Raudenbush, S. W., & Congdon, R. T. (1996). HLM: Hierarchical linear modeling withthe HLM/2L and HLM/3L programs . Chicago: Scientic Software International.

Deluga, R. J. (1994). Supervisor trust building, leader-member exchange and organizationalcitizenship behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , 67 ,315–326.

De Vries, R. E., Roe, R. A., & Taillieu, T. C. B. (2002). Need for leadership as a moderator of therelationships between leadership and individual outcomes. Leadership Quarterly , 13 ,

121–137.Dickson, M. W., Smith, D. B., Grojean, M. W., & Ehrhart, M. (2001). An organizational climate

regarding ethics: The outcome of leader values and the practices that reect them. LeadershipQuarterly , 12 , 197–217.

168 C. Harry Hui et al.

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 19/22

Ehrhart, M. G. (2004). Leadership and procedural justice: Climate as antecedents of unit-levelorganizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology , 57 , 61–94.

Emler, N., & Cook, T. (2001). Moral integrity in leadership: Why it matters and why it may bedifcult to achieve. In R. Hogan & B. W. Roberts (Eds.), Personality psychology in theworkplace ( pp. 277–298). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Evans, M. G. (1970). The effects of supervisory behavior on the path-goal relationship.Organizational Behavior and Human Performance , 5 , 277–298.

Farh, J. L., Podsakoff, P. M., & Cheng, B. S. (1987). Culture-free leadership effectiveness

versus moderators of leadership behavior: An extension and test of Kerr and Jermier’ssubstitutes for leadership model in Taiwan. Journal of International Business Studies , 18 ,43–60.

Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness . New York: McGraw-Hill.Fleishman, E. A. (1967). Performance assessment based on an empirically derived task taxonomy.

Human Factors , 9 , 349–366.Gibson, C., & Vermeulen, F. (2003). A healthy divide: Subgroups as a stimulus for team learning

behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly , 48 , 202–239.Glick, W. H. (1985). Conceptualizing and measuring organizational and psychological climate:

Pitfalls in multilevel research. Academy of Management Review , 10 , 601–616.Greenleaf, R. K., Frick, D. M., & Spears,L. C. (1996). On becoming a servant-leader . SanFrancisco:

Jossey-Bass.Gutek, B. A. (1995). The dynamics of service: Reections on the changing nature of

customer/provider interactions . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Hartline, M. D., & Ferrell, O. C. (1996). The management of customer-contact service employees: An empirical investigation. Journal of Marketing , 60 , 52–70.

House, R. J. (1971). A path goal theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly ,16 , 321–338.

Howell, J. P., Bowen, D. E., Dorfman, P. W., Kerr, S., & Podsakoff, P. M. (1990). Substitutes for leadership: Effective alternatives to ineffective leadership. Organizational Dynamics , 19 ,21–38.

Hui, C. H., Cheng, K., & Gan, Y. (2003). Psychological collectivism as a moderator of the impact of supervisor-subordinate personality similarity on employees’ service quality. Applied Psychology: An International Review , 52 , 175–192.

Hui, C. H., & Tan, G. C. (1999). The moral component of effective leadership: The Chinese case. In W. H. Mobley (Ed.), Advances in global leadership , Vol. 1 ( pp. 249–266). Stamford, CT: JAI.

Hurley, R. F. (1998). Customer service behavior in retail settings: A study of the effect of serviceprovider personality. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , 26 , 115–127. James, L. R. (1982). Aggregation bias in estimate of perceptual agreement. Journal of Applied

Psychology , 47 , 219–229. James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1993). Rwg: An assessment of within-group interrater

agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology , 75 , 306–309. Jermier, J. M., & Kerr, S. (1997). Substitutes for leadership: Their meaning and measurement –

Contextual recollections and current observations. Leadership Quarterly , 8 , 95–101. Johnson, J. W. (1996). Linking employee perceptions of service climate to customer satisfaction.

Personnel Psychology , 49 , 831–851.Kanungo, R. N., & Mendonca, M. (1996). Ethical dimensions of leadership . Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.Kerr, S., & Jermier, J. M. (1978). Substitutes for leadership: Their meaning and measurement.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 22 , 375–403.Kivlighan, D. M., Jr., & Tarrant, J. M. (2001). Does group climate mediate the group leadership-

group member outcome relationship? A test of Yalom’s hypotheses about leadership priorities.Group Dynamics , 5 , 220–234.

Service climate and leadership 169

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 20/22

Koene, B. A. S., Vogelaar, A. L. W., & Soeters, J. L. (2002). Leadership effects on organizationalclimate and nancial performance: Local leadership effect in chain organizations. LeadershipQuarterly , 13 , 193–215.

Kotler, P. (1999). Kotler on marketing: How to create, win, and dominate markets . New York:Free Press.

Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Doherty, M. L. (1989). Integration of climate and leadership: Examination of a neglected issue. Journal of Applied Psychology , 74 , 546–553.

Lam, S. K., & Schaubroeck, J. (2000). A eld experiment testing frontline opinion leaders as

change agents. Journal of Applied Psychology , 85 , 987–995.Ling,W.,& Fang,L. (1995).Theories on leadership andChineseculture: The formulationof theCPMmodel on leadership behavioranda Chinese implicit theory on leadership traits. In H. S. R. Kao,D. Sinha & S.H. Ng(Eds.), Effectiveorganizations and social values ( pp.269–286).New Delhi,India: Sage.

Litwin, G. H., & Stringer, R. A., Jr. (1968). Motivation and organizational climate . Boston, MA:Harvard University, Graduate School of Business Administration.

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Rich, G. A. (2001). Transformational and transactionalleadership and salesperson performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , 29 ,115–134.

Martin, J. (2002). Organizational culture: Mapping the terrain . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Misumi, J. (1985). The behavioral science of leadership . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. M., Mckee, D. O., & McMurrian, R. (1997). An investigation into the

antecedents of organizational citizenship behaviors in a personal selling Context. Journal of Marketing , 3 , 85–98.Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome .

Lexington, MA: Lexington.Organ, D. W. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Human

Performance , 10 , 85–97.Pillai, R., Schriesheim, C. A., & Williams, E. S. (1999). Fairness perceptions and trust as mediators

for transformational and transactional leadership: A two-sample study. Journal of Manage- ment , 25 , 897–933.

Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (1995). An empirical examination of the effects of substitutesfor leadership and leader behaviors at the individual-level and group-level of analysis. Leadership Quarterly , 6 , 289–328.

Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (1997). Kerr and Jermier’s substitutes for leadership model:

Background, empirical assessment, and suggestions for future research. Leadership Quarterly ,8 , 117–132.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Ahearne, M., & Bommer, W. H. (1995). Searching for a needle ina haystack: Trying to identify the illusive moderators of leadership behaviors. Journal of Management , 21 , 422–470.

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., & Fetter, R. (1993). Substitutes for leadership and themanagement of professionals. Leadership Quarterly , 4 , 1–44.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizationalcitizenship behaviors. Leadership Quarterly , 1 , 107–142.

Podsakoff, P. M., Niehoff, B. P., MacKenzie, S. B., & Williams, M. L. (1993). Do substitutes for leadership really substitute for leadership? An empirical examination of Kerr and Jermier’ssituational leadership model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 54 ,

1–44.Porter, L. W., & Bigley, G. A. (2001). Motivation and transformational leadership: Some

organizational context issues. In M. Erez, U. Kleinbeck & H. Thierry (Eds.), Work motivationin the context of a globalizing economy ( pp. 279–291). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

170 C. Harry Hui et al.

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 21/22

Rogelberg, S. G., Barnes-Farrell, J. L., & Creamer, V. (1999). Customer service behavior: Theinteraction of service predisposition and job characteristics. Journal of Business and Psychology , 13 , 421–435.

Sasser, W. E., & Arbeit, S. (1976). Selling jobs in the service sector. Business Horizons , 19 , 61–66.Schaubroeck, J., & Fink, L. S. (1998). Facilitating and inhibiting effects of job control and social

support on stress outcomes and role behavior: A contingency model. Journal of Organizational Behavior , 19 , 167–195.

Schneider, B., Ashworth, S., Higgs, A., & Carr, L. (1996). Design, validity, and use of strategically focused employee attitude surveys. Personnel Psychology , 49 , 695–705.

Schneider, B., Salvaggio, A. M., & Subirats, M. (2002). Climate strength: A new direction for climateresearch. Journal of Applied Psychology , 87 , 220–229.

Schneider, B., White, S. S., & Paul, M. C. (1998). Linking service climate and customer perceptionsof service quality: Tests of a causal model. Journal of Applied Psychology , 83 , 15–163.

Settoon, R. P., Bennett, N., & Liden, R. C. (1996). Social exchange in organizations: Perceivedorganizational support, leader-member exchange, and employee reciprocity. Journal of Applied Psychology , 81 , 219–227.

Srivastva, S. (1988). Executive integrity: The search for high human values in organizational life . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Strutton, D., Pelton, L. E., & Lumpkin, J. R. (1993). The relationship between psychological climateand salesperson-sales manager trust in sales organizations. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management , 13 , 1–14.

Turner, N., Barling, J., Epitropaki, O., Butcher, V., & Milner, C. (2002). Transformational leadership

and moral reasoning. Journal of Applied Psychology , 87 , 304–311. Villa, J. R., Howell, J. P., Dorfman, P. W., & Daniel, D. L. (2003). Problems with detecting

moderators in leadership research using moderated multiple regression. LeadershipQuarterly , 14 , 3–23.

Williams, M. L., Podsakoff, P. M., & Huber, V. (1992). Effects of group-level and individual-level variation in leader behaviours on subordinate attitudes and performance. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , 65 , 115–129.

Williams, M. L., Podsakoff, P. M., Todor, W. D., Huber, V. L., Howell, J. P., & Dorfman, P. W. (1988). A preliminary analysis of the construct validity of Kerr & Jermier’s Substitutes for Leadershipscales. Journal of Occupational Psychology , 61 , 307–333.

Yammarino, F., & Dubinsky, A. J. (1992). Superior-subordinates relationships: A multiple levels of analysis approach. Human Relations , 46 , 575–599.

Yammarino, F., & Dubinsky, A. J. (1994). Transformational leadership theory: Using levels of analysis to determine boundary conditions. Personnel Psychology , 47 , 787–816.

Yukl, G. (1994). Leadership in organizations . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.Zeithaml, V. A., & Bitner, M. J. (1996). Services marketing . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Received 18 October 2003; revised version received 7 November 2005

Appendix. Translation of items used to measure effective leadershipbehaviour (1) Your supervisor rarely ‘stabs people in the back’ or seeks personal vengeance.(2) Your supervisor often introduces unique insights and plans.(3) Even if problems at work arise, your supervisor rarely scolds subordinates

unreasonably.

(4) Your supervisor rarely curries favour with senior management or submitsunquestioningly.(5) Your supervisor can exibly cope with any unpredictable circumstances.(6) Your supervisor rarely gets too irrational and emotional at work.

Service climate and leadership 171

8/11/2019 Hui 2007 Joop Service

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/hui-2007-joop-service 22/22

(7) Your supervisor rarely abuses his/her power and authority.(8) Your supervisor respects the decisions made by subordinates in their area of

authority and responsibility.(9) Your supervisor rarely takes undeserved credit for other people’s work.(10) Your supervisor is mindful of meeting deadlines in his/her work.(11) Your supervisor listens to subordinates’ views and accepts their criticism with a

humble attitude.(12) Your supervisor handles issues decisively.

(13) Your supervisor rarely works through inappropriate relations or uses underhandedmeans to accomplish things for his/her own interest.

(14) Your supervisor provides useful suggestions when a subordinate encountersproblems at work.

(15) Your supervisor encourages his/her subordinates to freely voice their opinions.

172 C. Harry Hui et al.