Van Biezen EJPR2005

-

Upload

dianasofiars -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of Van Biezen EJPR2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 1/28

147European Journal of Political Research 44: 147–174, 2005

On the theory and practice of party formation and

adaptation in new democracies

INGRID VAN BIEZEN

University of Birmingham, UK

Abstract. In addressing issues of party development in contemporary democracies, many

of the recent discussions confuse notions of party formation with those of party adaptation.

The contention of this article is that the conceptual confusion of these two distinct processesundermines our understanding of party development, which is of particular importance in

the context of the more recently established democracies. Moreover, in order to contribute

to theory building on political parties more generally, it is necessary to differentiate between

the two. This article offers some theoretical contours for the study of party formation and

development, and empirically evaluates the patterns of organizational development in some

of the newer democracies in Southern and East-Central Europe. The analysis shows that

the external context of party formation has encouraged these parties to adopt an organiza-

tional style largely resembling their contemporary counterparts in the older democracies.

However, despite the resemblance between party organizations in the older liberal democ-

racies and the newly established ones, the paths of party development are best understood

as processes sui generis. The historical uniqueness of parties emerging as strong movements

of society, as opposed to agents of the state, is a path that is unlikely to be repeated in con-

temporary polities which democratize in a different institutional context.

In contemporary democracies, political parties have come to be seen as a sinequa non for the organization of the democratic polity. They are key institu-

tions for the expression of political pluralism and constitute the key channels

for political participation and competition. The relevance of parties formodern democracy is reflected in the recent proliferation of literature on polit-

ical parties, concentrating either on the established liberal democracies in

Western Europe or on more recently established democracies that have

emerged out of the ‘third wave’ (e.g., Biezen 2003; Dalton & Wattenberg 2000;

Diamandouros & Gunther 2001; Diamond & Gunther 2001; Gunther et al.

2002; Kosteleck 2002; Luther & Müller-Rommel 2002; Szczerbiak 2001;Webb

et al. 2002).

As a result of lack of conceptual clarity or absence of consistent analytical

frameworks, research on political parties has thus far led to contradictory or

at least inconclusive conclusions on a number of counts. One of the important

questions on which the jury is still out is the extent of variation that exists

between parties, and whether patterns of party development, within and

y¢

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden,

MA 02148, USA

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 2/28

148

between countries and regions, are to be seen in terms of convergence or diver-

gence. As a result, current research does not permit any conclusive answers to

a number of questions. Is there is a ‘generational’ or a ‘life-cycle’ effect of party

development? Does a party’s genetic structure continue to be reflectedthroughout subsequent processes of structural adaptation that lead to differ-

ent and co-existing types of party? Will some sort of a ‘period’ effect lead party

organizations to converge?

One extreme of the continuum is occupied by those who stress diversity,

while at the opposite extreme it is argued that the evidence indicates increas-

ing uniformity. While Coppedge (2001: 178) would argue that ‘each party is

unique’, for example, and Kitschelt (2001: 299) that diversity is much more

impressive than commonality, Bartolini and Mair (2001: 338), in the same

volume, contend that the increasingly standardized conditions in which parties

compete ‘call forth a new style of party, almost regardless of where these

parties are to be found or at what stage in the democratization process they

compete’.

While the degree of similarity or difference lies to some degree in the eye

of the beholder, the continuing scholarly disagreement indicates that, regard-

less of the direction in which the evidence points, there is a need for the further

development of differentiated theoretical frameworks. In this article, it is

argued that one factor that accounts for the weaknesses of theory building onpolitical parties is the conceptual confusion of the perspectives on party for-

mation with those of party adaptation, development and change. What ulti-

mately lies beneath the controversy over diversity or convergence is a lack of

understanding of the type of context that matters at a party’s initial forma-

tion, how internal party dynamics and the external environment account for

subsequent party development, and how period-effects impact on the genetic

structures of parties. Extrication of the body of theory on political parties into

distinct analytical frameworks of party formation and party change is imper-ative for any assessment of which institutions matter and how.

This article addresses these issues by focusing on political parties in the

recently established democracies in Southern and East-Central Europe. It

offers some theoretical contours for the study of party formation and party

development, for which it provides three possible scenarios. It then goes on to

evaluate empirically the patterns of party organization in these newer democ-

racies and assesses whether they should be seen in terms of difference or sim-

ilarity with each other and their counterparts in the older liberal democracies.

Finally, it is argued that, despite the many similarities that may exist between

parties in the contemporary West European democracies, party formation

and party development in the newer democracies should be understood as

processes sui generis.

ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 3/28

149

Party formation versus party adaptation

Theory building in the area of political parties thus far has been severely con-

strained by what could be called a ‘transformation bias’. Most existing partymodels are elaborated in the West European context and reflect models of

party change rather than models of party organization per se. The ‘catch-all

party’ (Kirchheimer 1966) and the ‘electoral-professional party’ (Panebianco

1988), for example, are both models signalling a process of transformation with

the classic mass party as explicit point of reference, while the more recent

‘cartel party’ (Katz & Mair 1995) likewise builds on previously existing types

of party organization. As Katz and Mair (1995: 6) assert, ‘the development of

the parties in western democracies has been reflective of a dialectical process

in which each party type generates a reaction which stimulates further devel-

opment, thus leading to yet another type of party, and to another set of reac-

tions and so on’. Logically, therefore, existing party models reflect this process

of party change, in which each model takes a previously existing one as point

of departure. While of some heuristic value, these models are difficult to apply

to the newer democracies.

Although the contemporary literature on political parties has made signif-

icant progress with regard to elaboration of models of party adaptation and

change, it has failed to confront the challenge of developing theories of party formation that can also be applied to cases other than the Western European

parties of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. LaPalombara and

Weiner’s (1966: 12) assertion made almost forty years ago, namely that

‘[g]reater theorizing is needed [. . .], because Duverger’s attempts to trace the

early development of parties to the emergence of parliaments and electoral

systems [can] hardly be applied to most of the developing areas’, also has a

clear relevance for parties that have been established recently in democratiz-

ing Southern and Eastern Europe. In order to contribute to theory buildingon political parties, however, it is imperative to avoid the transformation bias

that is inevitably associated with existing West European models of party.

What is needed is a theoretical framework that differentiates between

processes of party formation, on the one hand, and patterns of party devel-

opment, on the other.

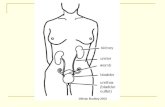

In theory, there are, broadly speaking, at least three possible scenarios of

party formation and party development. These can be distinguished on the

basis of the relevance of the external environment at the moment of party cre-ation,on the one hand,and the extent to which external factors, or rather inter-

nal dynamics, condition further party development, on the other. In the first

hypothetical scenario, the external environment of a party would be largely

exogenous to both party formation and development. In this case, parties

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 4/28

150

would share similar characteristics at birth by virtue of their ‘newness’,

and follow a similar process of development as a consequence of a largely

endogenous process of maturation and organizational institutionalization (cf.

Harmel & Svåsand 1993). This scenario is schematically represented in Figure1, in which the various basic shapes represent different models of party (in an

admittedly somewhat oversimplified manner). It follows from this scenario

that a synchronic analysis of parties at any point in time (t n) would reveal sim-

ilarities between parties at parallel stages in their life-cycle and diversity

among parties that find themselves in different phases. If parties are seen as

developing towards a certain end-stage of institutionalization, a convergence

of parties towards that final stage is to be expected. An example of such a per-

spective is offered by Michels, for example, according to whom all parties

would eventually succumb to the iron law of oligarchy, almost regardless of

their particular origins (see also Harmel 2002: 121). When comparing parties

in the newer democracies with their counterparts in the older ones, this sce-

nario would suggest that parties have developed along similar lines in both. If

this were the case, parties in the newer democracies, regardless of the period

in which they were created or the context in which they first emerged, would

also follow a trajectory from, say, cadre and mass parties to catch-all and cartel

parties.

ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

party B

party C

party A

t1 t2 t3 t4Time

Figure 1. Life-cycle scenario.

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 5/28

151

A second scenario would signal a ‘generation’ rather than a ‘life-cycle’

effect. Here, the conditions in which a party first emerges would largely deter-

mine its internal structure as well as the nature and strength of its external

linkages. In addition, the original format, or a party’s genetic structure(Panebianco 1988), would in essence continue to prevail despite subsequent

processes of internal development and external adaptation. This scenario is

shown in Figure 2. If this were to be the case, substantial differences between

parties created in different contexts and different eras of democratization are

likely to prevail, and similarity is likely to be found within contexts and

periods. Parties in the older democracies in Western Europe that emerged

during the ‘first wave’ of democratization in the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries would thus share many comparable features with one

another, but bear little resemblance to those that emerged out of the ‘third

wave’ in Southern Europe in the 1970s, in Latin America in the 1980s or

in Eastern Europe in the 1990s. According to this scenario, commonalities

within, and variation between, each of these waves is likely to constitute the

norm.

As in the first scenario, any synchronic analysis at time t n, including parties

of a different generation is likely to reveal diversity. Unlike the life-cycle sce-

nario, however, an analysis over time would reveal that this would not indi-

cate parties in the newer democracies are lagging behind on their counterparts

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

t1 t2 t3 t4

party B

party C

party A

Time

Figure 2. Generation effect.

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 6/28

152

in the earlier established democracies because of their more recent arrival on

the stage. Rather, it would suggest that context-specific types of parties

co-exist, and that parallel patterns of development emerge across regions and

periods. The development of parties in Western Europe from mass to catch-all and cartel parties would then be an historically unique experience that is

unlikely to be repeated in different environments and different periods of

democratization. Parties in the newer democracies would follow a different,

equally distinctive, trajectory brought about by the unprecedented nature of

more recent democratization processes.

A third scenario indicates a ‘period-effect’ on party formation and devel-

opment. In this scenario, as in the second, the external environment would

have a significant impact on the emerging types of party. However, in contrast

to the ‘generational’ model, changes in the party’s external conditions would

continue to exert a critical influence, to the point of having overall homoge-

nizing effect, compelling parties to adapt to similar types (see Figure 3). The

influence of the immediate environment would thus outweigh the relevance

of genetic origins or internal party dynamics. Even if newly created parties

would not immediately start out as near duplicates of already existing ones,

exogenous pressures would be such that they would ultimately push parties

towards convergence.

If this scenario were to be the most accurate, a large degree of similaritybetween parties in similar environments would emerge in any given period,

ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

party B

party C

party A

t1 t2 t3 t4Time

Figure 3. Period effect.

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 7/28

153

almost regardless of the stage of the democratization process in which parties

can be found or the period in which they first started to compete. In contem-

porary democratic polities, parties in newer democracies would show signifi-

cant similarities to those in the older liberal democracies. From this scenario,it follows that parties in the newer democracies would miss out earlier stages

of party development, such as the mass party – and other stages for that

matter – (cf. Kopeck 1995) and would make what Smith (1993: 8) has called

an ‘evolutionary leap’ towards more contemporary models in Western Europe.

The available empirical evidence suggests that the first scenario is proba-

bly an implausible one. Moreover, although the argument itself may serve an

important heuristic purpose, there are good reasons to dismiss this scenario

on theoretical grounds as well, as it is arguably unlikely that the conditions in

which a party first starts to operate would have little or no impact on its inter-

nal structure. This is especially true for models that approach parties in terms

of their linkages with their external environment and attempt to locate them

in relation to their position vis-à-vis society and the state. It is rather more

likely that party formation and the nature of the emerging linkages between

parties, citizens and the state are conditioned by exogenous factors such as the

institutional context, historical legacies or the nature of the previous regime

(e.g., Kitschelt 2001). What may also shed light on the variety of parties is the

sequence of development, and particularly the timing of party formation vis-à-vis the establishment of responsible government and the introduction of uni-

versal suffrage (Daalder 2001; see also Biezen 1998). Party formation may also

be driven by social, cultural and economic imperatives, such as the cleavage

structure of society, or contingent factors, such as access to the mass media and

availability of state subsidies.

Hence, while parties may be considered independent institutional forces

that act upon political, social and economic development or change, they

should also be regarded as in some way dependent and responding to theirenvironment. However, the literature has thus far been unsuccessful in

accommodating parties as responsive to their structural environment with

their capacity to operate as autonomous actors, as it has also failed to reflect

on their dual nature as both institutions and agents. The contention in this

article is that that context and conduct are necessarily interrelated and, more

specifically, the behaviour of party leaderships and party strategies cannot be

seen to be independent from the structural context in which the party is

embedded. Theories of party formation should thus rather seek a more neo-

institutionalist approach that emphasizes the fact that existing structures make

a difference for the choices that will be made, and concentrate primarily on

environmental factors external to the party as key determinants for party for-

mation. In the perspective adopted here, therefore, the basic assumption is that

y¢

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 8/28

154

the strategies of parties are shaped by both the institutional context and the

historical setting in which they operate (cf. Aldrich 1995). The environment in

which the party begins to operate is primarily responsible for the type of party

that emerges. Moreover, the changing environment is often, as Katz and Mair(1995: 18) suggest, the ultimate source of party change. In other words, while

strategies of party formation and change might be contingent and subject to

choice, contingency is also subject to structural constraints (see Karl 1990).

Thus no study of party formation can afford to ignore the wider context in

which parties first emerge. The following sections will analyze in more detail

how the context of party formation has shaped the opportunities and con-

straints for strategies of political mobilization and organization in some of the

‘third wave’ democracies in Southern and East-Central Europe.1

The context of party formation

In recent processes of democratization, many parties began their organiza-

tional lives with almost no real presence on the ground. In addition, the par-

ticular path towards democracy allowed for relatively little time to expand the

extra-parliamentary party organization prior to the first democratic elections.

More generally, and in contrast with many of the externally created parties(in particular socialist ones) in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century

Western Europe, a strong membership organization was not perceived to be

an ‘organizational necessity’ (Epstein 1980). Indeed, a membership organiza-

tion was seen to provide few benefits to the party not already available from

alternative human or financial resources.

Another important point to recognize here is that many of the parties

developing in these new democracies had an institutional, rather than societal,

origin and generally did not follow the traditional West European path of party formation by which parties were created to represent the interests of a

particular segment of society that can be defined in structural terms (see Lipset

& Rokkan 1967). Instead, party formation was often based on politicized atti-

tudinal divisions regarding the desirability, degree and direction of regime

change rather than politicized social stratification. As Schöpflin (1993: 259)

observed for the Eastern European context:

At a deeper level, the post-communist contest was not so much about

policies as about polities. The key issues centered on the nature of the

constitutional order and the rules of the political game, rather than the

allocation of resources that makes up the standard fare of politics in

established democracies.

ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 9/28

155

Since they were often not created as the agents of a defined segment of society,

the social basis of party politics had to be created after the transition to democ-

racy. Hence the answer of Minister Syryjczyk of the Mazowiecki Government

in Poland to the question of whom he represented: “I represent subjects thatdo not yet exist” (quoted in Staniszkis 1991: 184). Because parties lacked a

‘natural constituency’ and an ‘electorate of belonging’, they would not provide

the political articulation of pre-defined segments of the electorate. The lack of

partisan identities or stable party preferences in the unaligned electorates,

moreover, compelled the recently created parties to make a strategic choice

for expansive electoral mobilization rather than partisan mobilization. While

mass parties in the old democracies generally started out as organizations of

society demanding participation, parties in the new democracies were faced

with the challenge of enticing citizens who already have rights of participation

to exercise those rights.

The relatively time-consuming and labour-intensive strategy of partisan

mobilization by which parties create a structural and permanent anchoring of

the party within society through an active recruitment of members and the

expansion of the organization on the ground is usually only chosen when no

other feasible options are available (Kalyvas 1996). Parties in new democra-

cies were rather inclined to turn to the electorate at large, which, assisted by

the availability of modern mass media, was generally perceived as the mosteffective strategy for creating alignments with the electorate and enhancing

the chances for party survival. Indeed, electoral, rather than partisan, mobi-

lization was also the strategy that began to be preferred increasingly in the

West. As it was famously articulated by Kirchheimer (1966: 184), parties

during the postwar years were ‘[a]bandoning attempts at the intellectual and

moral encadrement of the masses [and] turning more fully to the electoral

scene, trying to exchange effectiveness in depth for a wider audience and more

immediate electoral success’. As will be discussed at greater length below, thecontext of party formation in recent cases of democratization provided few

incentives for the prioritizing of organizationally penetrative, as opposed to

electoralist, strategies.

Parties and society

Although most parties in the newer democracies formally adopted the model

of the party as a membership organization, thus seemingly taking their cue

from their older West European counterparts in which party structures are

based on formal membership registration and a network of local branches, the

notion of an active and committed rank-and-file typical of the classic West

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 10/28

156

European mass party is virtually non-existent. Membership organizations tend

to be small and have relatively little participatory substance. This is most

evident from the low membership figures (see below), but can also be seen

from the comparatively high levels of professionalization, for example. In theolder democracies, the diminished importance of voluntary labour is demon-

strated by the substantial increase in the number of paid employees at the

party central office during the postwar period. In the late 1980s, parties in

Western democracies recorded, on average, 6.3 paid employees for every

10,000 party members (Krouwel 1999: 91). The equivalent figure for Czech and

Hungarian parties, by contrast, amounted to 16.7 paid employees per 10,000

party members at the party central office in the late 1990s. This much higher

level of professionalization indicates that internal party activity members are

clearly of even less relevance and paid professionals of more importance than

in the older democracies.

In addition, the obligations of the membership to the party tend to be only

minimal and generally do not exceed the payment of the membership fees or

undemanding requirements such as the acceptance of the party programme

or statutes. It is only in parties with a longer organizational history, such as the

former ruling communist parties and their satellites in Eastern Europe or the

previously clandestine communist and socialist parties in Southern Europe,

that an active level of participation and some degree of commitment to theparty is sometimes required from their members. Virtually without exception,

however, these older parties are now gradually abandoning their organiza-

tional and ideological inheritance.This process can be understood as the adap-

tation of party organizations to an environment in which a substantial level of

engagement of the membership in internal party activities is no longer desir-

able, in which an active party membership is seen to be less important, and in

which the traditional role of the party member is increasingly fulfilled by party

officials and paid professionals.What further underscores the marginal relevance of the party membership

in the context of the new democracies is the relative indifference of party elites

towards their memberships. This is reflected by a relatively acquiescent atti-

tude towards low membership levels, the absence of membership recruitment

campaigns and also, rather strikingly, in the widespread practice of fielding

independent candidates for public office under the party label. This is a preva-

lent phenomenon in post-communist politics in particular, which is partly

induced by the negative connotation associated with the institution of the

political party. For Russia, for example, Moser (1999: 148) observes that can-

didates would sometimes ‘intentionally hid[e] their ties to a party in fear that

their party affiliation would alienate potential supporters’. By expanding their

reach outside the channels of the party organization in performing their

ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 11/28

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 12/28

158 ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

Table 1. Party membership change, 1980–2000

1980–1981 1990–1992 1998–2000 % change

Portugal

PCP 187,018 163,506 131,504 -29.7

PS 105,537 69,351 100,000 -5.2

PSD 38,128 137,931 75,000 +96.7

CDS/PP 6,732 26,801 40,000 +494.2

Total 337,415 397,589 346,504 +2.7

M/E 4.87 4.95 3.99 -18.1

Spain

PCE 160,000 44,775 26,253-

83.6IU 57,303 70,000 +22.2

PSOE 97,356 262,854 410,000 +321.1

AP/PP 56,319 284,323 601,731 +968.4

UCD 136,106 - - -

Total 449,781 649,255 1,107,984 +146.3

M/E 1.68 2.19 3.35 +99.4

Hungary

MSZP 59,000 39,000-

33.9SZDSZ 24,000 16,000 -33.3

MDF 33,800 23,000 -32.0

KDNP 3,500 10,000 +185.7

FKGP 40,000 60,000 +50.0

FIDESZ-MPP 5,000 15,600 +212.0

Total 165,300 163,600 -1.0

M/E 2.11 2.03 -3.8

Czech RepublicKS M 354,549 136,516 -61.5

SSD 13,000 13,000 0.0

KDU- SL 100,000 62,000 -38.0

ODS 22,000 22,000 0.0

Total 489,549 236,516 -52.3

M/E 6.33 2.91 -54.0

Note: M/E = party membership as a percentage of the electorate.

Sources: Biezen (2003); Mair & Biezen (2001).

C ˇ C ˇ

C ˇ

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 13/28

159

2000, membership levels almost doubled, although this rather exceptional

increase should be qualified by underlining that it started from a relatively low

base in 1980. Nevertheless, increasing membership in the Spanish case pro-

vides a rather atypical example, in particular because it is a new party (thePartido Popular – PP) that has experienced the most dramatic increase and

now records the highest level of party membership of all Spanish parties. This

suggests that,despite the relevance of the external environment at the moment

of creation, internal party dynamics can in principle make a difference for sub-

sequent development. In the case of the PP, for example, membership recruit-

ment was adopted deliberately in the mid-1980s as a strategy for electoral

expansion.

That the organizational linkages between parties and society are generally

weakly developed can also be seen from the low extensiveness of party orga-

nizations. Newly created parties in post-communist polities in particular have

established such a small number of local branches that, on average, the reach

of party organizations does not exceed a quarter of the country.2 One of

the crucial consequences of the weak presence of party organizations on the

ground is the low profile of parties in local politics,and especially in the smaller

municipalities, which in post-communist democracies tends to be dominated

by independent candidates. A recent study of local government and elections,

for example, revealed that, in at least three of the East-Central Europeancountries (Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic), the vast majority of the

candidates contesting and elected in municipal elections were without party

affiliation (Horváth 2000). This low territorial implantation of party organiza-

tions leaves parties by and large remote from large sectors of society, and, con-

sequently, renders partisan linkages more generally of little relevance as a

channel to structure the relationship between parties and society.

Finally, and in addition to the weakness of the partisan linkage per se, it is

important to emphasize that the nature of the relationship between partiesand society tends to be shaped through direct rather than indirect linkages.

Very few, if any, of the parties report any formal linkages with trade unions or

with organized interest associations. Although close relationships between

parties and trade unions and other interest organizations may exist in politi-

cal practice, they tend to consist of a direct linkage rather than an indirect one

in which the union is partially incorporated within the organizational struc-

ture and acts as a transmission belt of the party. Relationships furthermore

tend to be of a pragmatic rather than ideological nature, in which neither the

union nor the party restricts contacts exclusively to one another. Only a small

minority of parties, such as the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) or the

Hungarian Christian Democrats (KDNP), maintain a strong organic linkage

with like-minded associations and movements (Biezen 1998; Enyedi 1996).

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 14/28

160

They provide an exception to a general organizational pattern, however, in

which an exclusive commitment to a particular fraternal interest association

is normally absent.

The autonomous relation between parties and organized interests cannotbe attributed exclusively to the weak development of civil society; it is also

the result of a predisposition against a particular (indirect) model of party

organization. This is a product of the context of a contemporary democratiz-

ing regime in which parties are generally not born out of politicized social

interests and in which the external environment and the sequence of organi-

zational development leaves them few incentives to develop a close and for-

malized linkage to organized interest movements (cf. Waller et al. 1994). The

environment can be seen to exert similar pressures on many of the older

parties, to the point that their historical linkages with organized interests

have now begun to unravel. Where strong linkages existed historically, they

have become much looser with time. The organizational and programmatic

commitment between parties and unions has been abandoned quite decisively

in the case of the former ruling communist parties and their allied trade

unions, while in the Southern European context both the Spanish Communist

Party (PCE) and the Socialist Party (PSOE) have gradually disentangled

themselves from their traditionally affiliated unions (Biezen 1998; Gillespie

1990).All of the arguments cited above – the weak position of party members

vis-à-vis paid professionals, the indifference towards a large and active mem-

bership, the low levels of party affiliation, the limited reach of party organi-

zations, and the weakness of the linkages between parties and organized

interests – suggest that parties in new democracies lack the capacity and

resources to build up mass organizations. In this sense, the tendency towards

a declining importance of the partisan linkage observed for the established

Western European democracies, where ‘parties are weakening as elite-masslinkages’ (Andeweg 1996: 158), is also visible (and even more forcefully so) in

the context of these newer democracies. It appears to be an electoral rather

than partisan linkage that almost exclusively shapes the relationship between

parties and society, while the role of parties in providing the linkage between

society and the state is becoming increasingly irrelevant (cf. Katz 1990).

Another factor is also at play here that is crucial to the development of

organizational styles and derives from the wider context within which party

linkages can be facilitated: the possibility for public funding of party activity.

As will be shown below, the widespread availability of state funding can be

seen to offer parties additional opportunities to bypass the creation of struc-

tural partisan linkages with society.

ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 15/28

161

Encouraging étatisation through public funding

For modern parties in the established Western democracies, the introduction

of state subventions to parties has encouraged important changes in the wayin which parties organize. Most importantly, the increasing availability of state

subventions has served to strengthen the orientation of parties towards the

state while it has, at the same time, contributed to their shifting away from

society (Katz & Mair 1995). Even more so than in the established European

democracies, public funding plays a pivotal role in the financing of parties in

many of the newer democracies, if only because direct state support was often

introduced at an early stage of the democratization process and, for many

newly emerging parties, in the initial phase of party formation. Although the

introduction of state support often occurred without much debate on the role

public money should play in the financing of democratic politics (e.g., Castillo

1989: 179), state funding has reinforced the organizational styles already

encouraged by the context in which parties first developed and decisively

strengthened party-state relations from the outset (see Lewis 1998).

In the mid-1970s, the Southern European countries were the first of the

‘third wave’ democracies to introduce public funding of parties on a relatively

large scale, an example which has since been followed by many of the post-

communist democracies established in the early 1990s. In a comparative studyof the practice of political finance in 17 Eastern Europe countries, Ikstens

et al. (2002) find that three-quarters of the post-communist polities provide

direct public subsidies to political parties and candidates, while all of them

offer indirect state subsidies. Given that state support was introduced when

most parties were still in an initial stage of party formation and therefore

usually lacked alternative organizational resources, public funding was always

likely to play a critical role. Indeed, the state appears to be the predominant

player in party financing in many of the post-communist countries in Europeas well as in their Southern European counterparts. To the major Portuguese

and Spanish parties, for example, the state contributes on average some 75

to 85 per cent of their total income (Biezen 2000a). In most of the post-

communist democracies in Eastern Europe, the role of the state in party

financing tends to be of equal significance (Lewis 1998; Szczerbiak 2001).

Table 2 shows the relative importance of the state for the financing of

parties and election campaigns in some of the newer democracies in Southern

and East-Central Europe. The figures here are expressed as a percentage of the total party income and present the averages per party over a number of

years.3 They also distinguish between three broader categories of monetary

income: the state (including subsidies for election campaigns and routine

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 16/28

162 ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

T a b l e 2 . F i n a n c i n g p a r t i e s i n n e w d e m o c r a

c i e s

C o u n t r y

P a r t y a n d p e r c e n t a g e

M e a n

P o r t u g a l ( 1 9

9 5 – 2 0 0 2 ) a

P C P

P S

P S D

C D S - P P

S t a t e s u b v

e n t i o n s

1 8 . 5

3 0 . 5

3 4 . 0

2 9 . 4

2 8 . 1

P r i v a t e f u n d r a i s i n g

1 3 . 9

4 7 . 9

6 2 . 5

2 8 . 5

3 8 . 2

O t h e r

6 7 . 6

2 1 . 6

3 . 7

4 2 . 1

3 3 . 8

S p a i n ( 1 9 8 8 – 1 9 9 7 ) b

P C E / I U

P S O E

A P / P P

S t a t e s u b v

e n t i o n s

7 0 . 8

7 7 . 0

8 1 . 5

7 6 . 4

P r i v a t e f u n d r a i s i n g

1 3 . 4

1 5 . 3

1 5 . 0

1 4 . 6

O t h e r

1 5 . 9

7 . 6

3 . 5

9 . 0

H u n g a r y ( 1 9

9 0 – 1 9 9 6 )

M S Z

P

S Z D S Z

M D F

K D N P

F K G P

F I D E S Z

S t a t e s u b v

e n t i o n s

3 9 . 2

7 8 . 2

2 8 . 8

7 8 . 4

8 7 . 7

2 2 . 5

5 5 . 8

P r i v a t e f u n d r a i s i n g

7 . 7

1 2 . 8

5 . 8

8 . 3

7 . 0

0 . 6

7 . 0

O t h e r

5 3 . 2

9 . 0

6 5 . 6

1 3 . 4

5 . 3

7 6 . 8

3 7 . 2

C z e c h R e p u

b l i c ( 1 9 9 5 – 1 9 9 6 )

O D S

O D A

K D U - S L

S S D

K S

M

S t a t e s u b v

e n t i o n s

5 9 . 5

4 7 . 9

4 1 . 4

5 8 . 3

3 1 . 3

4 7 . 7

P r i v a t e f u n d r a i s i n g

3 0 . 2

4 2 . 7

2 1 . 5

3 . 1

3 4 . 2

2 6 . 3

O t h e r

1 0 . 4

9 . 5

3 7 . 1

3 9 . 6

3 4 . 6

2 6 . 2

N o t e s : s o u r c e

s o f i n c o m e ( p e r c e n t a g e o f t o t a l i n c o m e ) ; a e l e c t i o n c a m p a

i g n s o n l y ; b e x c l u d i n g e l e c t i o n c a m p a i g n s .

S o u r c e s : s e e B i e z e n 2 0 0 3 .

C ˇ

C ˇ

C ˇ

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 17/28

163

operational activities), private or voluntary fundraising (including member-

ship fees, individual and corporate donations), and other sources (which may

include bank loans, revenues from real estate or unspecified income). Even

though the sometimes large category of ‘other’ sources of income makesa more detailed analysis virtually impossible,4 the evidence presented here

clearly demonstrates the unequivocal importance of state support to political

parties. State subventions amount to almost 30 per cent of total party income

in the case of Portugal, about half of annual party income in post-communist

Hungary and the Czech Republic, and over three-quarters in the case of Spain

(for a breakdown and more detailed analysis, see Biezen 2003: Chapter 8).

Moreover, with the exception of Portugal, the state has assumed the role of

most important financial contributor to party activity.5 In general, the picture

that emerges for all these new democracies is that, although the relevance

of private and voluntary fundraising has not entirely been relegated to the

margins, these types of contributions are clearly of less significance than public

subsidies. For many parties, the financial dependence on public subventions is

such that the state is often (at least formally) the single most important finan-

cial contributor to party activity, while some parties are virtually entirely

dependent on public money.

Given the generally low levels of party affiliation, membership subscrip-

tions have always constituted a practically irrelevant source of revenue. Onlyfor a few parties does the membership organization continue to be of impor-

tance in financial terms. All of these are parties with a longstanding organiza-

tional history, however, that have preserved the legacy of relatively large

membership organizations. These include the Portuguese Communist Party

(PCP) and the former ruling Communist Party in what is now the Czech

Republic (KS M). The general tendency, however, is one that indicates the

relative unimportance of the membership organization for party financing,

with the financial contribution of membership subscriptions reaching levelsapproximating zero in extreme cases such as that of the (former) Young

Democrats (FIDESZ) in Hungary.

The findings in Table 2 indicate that state subventions in these four new

democracies, on average, constitute 52 per cent of the total party income. In

financial terms, parties in new democracies thus appear even more firmly

entrenched in the state than parties in the long-established democracies,

where the average share of public funds to the total income of Western Euro-

pean parties in the late 1980s amounted to only some 35 per cent (Krouwel

1999: 82). Given that the figures presented in Table 2 exclude the financing of

routine organizational activity in Portugal, as well as the financing of election

campaigns in Spain, the evidence presented here is in fact likely to underesti-

mate the overall importance of state funding. In terms of their strong linkage

C ˇ

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 18/28

164

with the state, therefore, these Southern and East-Central European parties

clearly reflect the tendency observed by Katz and Mair (1995) for Western

Europe, by which state subventions become a principal resource for parties

in a modern democracy and by which parties increasingly become part of the state apparatus rather than the being the representative agents of civil

society. Even though the advent of public subsidies may imply that other

sources of income have become entirely irrelevant (cf. Pierre et al. 2000), the

relevance of state subventions is extraordinary and may indeed, as Katz (2002:

115) has argued ‘represent a fundamental change in the character of the party,

furthering its transformation from a private association into a semi-public

entity’.

While the introduction of public funding in Western Europe contributed

significantly to parties’ shifting orientation from society towards the state, in

the newer democracies the linkage with the state came immediately in the

wake of democratization, resulting in no such shift occurring and leaving

parties entrenched in the state from the very outset. The parties’ early finan-

cial dependence on the state also appears to have removed a key incentive to

establish a more structural financial linkage with civil society. Notwithstand-

ing its continuing importance for some of the older parties, the membership

organization has generally lost virtually all relevance in financial terms. In the

four recently established democracies analyzed here, the share of membershipfees to the total party income, on average, amounts to between 5 and 10 per

cent. This figure again stands out in sharp contrast to parties in the older West

European democracies, where, despite a distinct decline from the beginning

of the 1950s onwards, almost 30 per cent of income still originated from mem-

bership fees by the late 1980s (Krouwel 1999: 76). Hence, parties in both East-

Central and Southern Europe present unequivocal evidence of the pace by

which tendencies observed for the long-established democracies tend to be

reinforced in the context of a new democracy.The extensive availability of and dependence on public funds has not only

created strong party–state linkages, but also further centralized the locus of

power within the party (cf. Nassmacher 1989; Panebianco 1988). More specif-

ically, increasing dependence on the state as the predominant financier

coupled with the allocation of state subventions to the party central office has

resulted in a corresponding concentration of power within the party. Hence,

in terms of internal organizational dynamics, the extreme financial depen-

dence on the state has further encouraged the oligarchization of parties.

Parties in new democracies, therefore, are primarily elitist organizations,

although ones in which the locus of power is to be found within the extra-

parliamentary executive rather than in the party in public office (see below).

ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 19/28

165

The balance of power

Parties developing in early democratizing Western Europe gradually passed

through the consecutive stages of legitimation, incorporation, representationand executive power (Rokkan 1970). While traversing these four stages

marked a long-term process of organizational development, party formation

in newer democracies occurred rapidly and in the aftermath of democratiza-

tion and politicization (Mair 1997). Furthermore, newly emerging parties were

created from within the party in public office, or would acquire parliamentary

representation (and often also government responsibility) almost immediately

after their formation. In contrast to many of their West European counter-

parts, therefore, few of the newly created parties in ‘third wave’ democracies

can be seen as ‘externally created’. In many cases, they appeared confined to

a parliamentary (and sometimes governmental) existence, as well as lacking

an established organizational structure extending much beyond these offices.

Because parties in the newer democracies were usually created by a small

group of prominent elites at the national level, party structures would largely

develop from the top-down. This is in sharp contrast to most of the externally

created parties in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Western

Europe, in particular socialist and religious ones, where mass mobilization

preceded the creation of national party organizations (e.g., Bartolini 2000;Kalyvas 1996) and were thus largely built from the bottom up.

The impact of their internal creation and top-down development is

reflected in the high levels of centralization and in the fact that many party

organizations are concentrated around their party leaderships. Indeed, many

parties stand out for having concentrated power at the highest echelons of the

party in the hands of a small elite, to the point that they reveal strong oli-

garchic tendencies (Machos 1999). The ultimate authority on financial deci-

sions, for example, usually rests with the national executives, signalling a highdegree of centralization which, given the centralized allocation of state sub-

ventions, is further enhanced by the importance of public funding. Candidate

selection procedures tend to be highly centralized as well. Even in parties

where the selection process is formally carried out according to a bottom-up

procedure, the national executive often enjoys – in practice and by party

statute – the ultimate authority to veto candidates or to decide on their rank

order on the party lists. Moreover, the influence of the national executive on

the selection of candidates also frequently extends to the selection of publicofficeholders on the local and regional levels. Even in parties where the role

of the membership might be seen as more meaningful because it is given a

direct voice in the selection of the party leader, as in the case of the Spanish

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 20/28

166

Socialist Party (PSOE), the party leadership retains such a strong role in the

selection of candidates that the extent to which the primaries have actually

increased the influence of the membership is questionable (Hopkin 2001).

The predominant position of the party leaderships is further encouragedby two factors that derive from the wider context in which these parties

operate – namely the small and weakly institutionalized membership organi-

zations and the pervasiveness of television. More specifically, the combined

impact of both these factors has contributed significantly to a highly person-

alized style of politics (Pasquino 2001). While a high degree of personaliza-

tion is virtually inevitable in a context where the identity of many of the newly

created parties has yet to crystallize beyond the personal appeal of the party

leader (cf. Sartori 1968), the persistent weakness of the party organizations

has enabled party leaders to continue to monopolize the public image of their

parties beyond the early stages of the transition.

The predominance of the party leaderships is reflected in highly personal-

ized networks around the party presidents and in the fact that personalist

features tend to dominate internal party conflicts. Indeed, a high level of intra-

party instability encouraged by the particular political style of the party leader

is typical for new parties in a new democracy.6 This stands in sharp contrast to

the established liberal democracies, where the number of splits and mergers

has generally been relatively limited (Mair 1990), and further underlines theweaker party loyalties and lower levels of party institutionalization in newer

democracies. The personalization of party politics is further suggested by pres-

identialized party structures that are often codified in the party statutes by the

formal institutionalization of the party presidency as a ‘unipersonal’ and priv-

ileged party office with decision-making authority in key areas.

In many parties, selection of the members of the party executive, control

over the party apparatus, employment of party personnel, financial manage-

ment of the party or selection of candidates for public office largely hinge uponthe authority of the party leader, to the point that their party organizations

can be classified as ‘presidential-authoritarian’ or as ‘president-oriented oli-

garchies’ (Machos 1999). More generally, the prevailing model of party orga-

nization in the new democracies is hierarchical and top-down, with little room

for a membership organization of any importance, with a predominant party

leadership and a tendency towards personalization. A illustrative example in

this respect is provided by the radical transformation of the former youth

movement FIDESZ (now FIDESZ-MPP) in Hungary from a collegial to a

personal leadership with extensive prerogatives, and from a grassroots move-

ment to an ‘extremely oligarchic’ and highly professionalized party structure

designed for winning office (Balász & Enyedi 1996). This represents a shift

towards what symbolizes the predominant leadership style and type of party

ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 21/28

167

organization. It also clearly underlines that pressures to increase the electoral

orientation are difficult to withstand and a participatory orientation is rela-

tively easily sacrificed when confronted by the need for organizational effi-

ciency and electoral expansion.A final observation on the internal balance of power concerns the position

of the party in public office, and its relationship with the party executive in

particular. Given a sequence of party development by which the party in

public office emerges first, and given that it is this face of the party that initi-

ates and controls subsequent organizational development, we would anticipate

that, rather than acting as the agent of the extra-parliamentary party or the

party on the ground, the party in public office maintains its early privileged

position and continues to occupy a predominant position within the overall

party organization. Indeed, the tendency for members of national executives

and public officeholders to accumulate political mandates produces an overall

picture of party executives being strongly invaded by public officeholders.

However, party statutes, as well as political practice, signal a remarkably pow-

erful position for the party executive to the point that the party in public office

should actually be seen as subordinate to the extra-parliamentary executive.

Rather than having acquired an autonomous status vis-à-vis the extra-parlia-

mentary party, let alone that of the predominant body, the party in public office

should in fact be seen as the least privileged face of party organization. Thisis indicated by the distribution of financial and human resources (e.g., the dis-

tribution of state subventions to the advantage of the extra-parliamentary

party) as well as its much higher level of professionalization in comparison to

the parliamentary party. Parties in new democracies thus counter the trend

recently observed for many Western European countries where the party in

public office has generally been the main beneficiary of the changing rela-

tionship between the different faces of the party organization (Katz & Mair

1993; Heidar & Koole 2000). Models of party formation and organizationaladaptation established for the older democracies are thus apparently of

limited value as the internal creation of parties appears to have little relevance

for the overall power balance between the extra-parliamentary party and the

party in public office. Nor has their birth in an environment of generous public

funding and widely available mass media tipped the scales in favour of the

party in public office.

What should be at the core of any explanation of the tendency to

strengthen the position of the party executive at the expense of the party in

public office for parties in the recently established democracies is the desire

to increase party cohesion and so reduce the potentially destabilizing conse-

quences of emerging intra-party conflicts that are an inevitable by-product of

the context of weakly developed party loyalties and a generalized lack of party

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 22/28

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 23/28

169

linkages, the reduced relevance of party members, the predominance of pro-

fessionals and party leaderships, the importance of public funding and the

parties’ assimilation with the state (Beyme 1996; Katz & Mair 1995). We do

not witness unique types of party in these newer democracies, however,at leastnot to the extent that they should be perceived as fundamentally different

from existing models in the established democracies. Any existing variation

between parties in old and new democracies can best be interpreted as dif-

ferences in degree rather than in kind.

What this suggests in terms of the scenarios of party formation and devel-

opment outlined above is that the institutional context and the period in which

parties in the new democracies emerged have encouraged them to converge

towards their counterparts in the West. However, it should also be apparent

that the patterns of party formation and the paths of party development in old

and new democracies are fundamentally different and are best understood as

processes sui generis. In other words, despite the many similarities between

parties in old and new democracies that exist today, they have arrived at this

stage by setting off from two entirely different points of departure. At the risk

of oversimplification, the process for mass parties in the old democracies might

be summarized as ‘a movement from society towards the state’. In many of

the European polities that constitute part of the ‘third wave’, in contrast,

parties can be seen to originate as parties of the state. Where they have sub-sequently expanded their organizations beyond the confines of state institu-

tions, they have often reached out only minimally towards society.

Underlining the distinction between these two patterns should contribute

to a better understanding of processes of party formation and organizational

development more generally. It also helps to avoid the transformation bias as

well as the teleological connotations that are almost inevitably inherent in

attempts to interpret party development in new democracies in terms of ‘evo-

lutionary leaps’ towards the models existing in the older liberal democracies.Although parties in old and new democracies may be seen to converge, and

together can be seen to represent a mode of party organization that is clearly

different from early post-democratizing Western Europe, it might be the

parties in the West European polities that are developing towards the stan-

dard currently set by the new democracies, rather than the other way around

(cf. Padgett 1996). In this sense, therefore, our perspective not only reveals

what is different about party formation and organizational development in

new democracies, but also highlights what has been distinctive about the tra-

jectories in Western Europe itself. It underlines the uniqueness of the emer-

gence of parties as strong movements of society, as opposed to agents of the

state, a path that is unlikely to be repeated in a different period and a differ-

ent institutional context of party formation.

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 24/28

170

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was presented at the annual meeting of the

American Political Science Association in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 2003.Attendance at the conference was supported by a travel grant from the British

Academy, which is gratefully acknowledged. I would like to thank the panel

participants, the two anonymous referees as well as Giovanni Capoccia,

Jeremy Jennings, Petr Kopeck and Peter Mair for their valuable comments.

The usual disclaimer applies.

Notes

1. This research is part of a larger comparative analysis on party formation and organiza-

tional development in the new democracies of Southern and East-Central Europe (see

Biezen 2003), from which, unless otherwise indicated, the empirical evidence presented

here is drawn.

2. This figure excludes parties with some degree of organizational continuity, such as the

Czech KS M and KDU- SL, which have preserved a notable legacy in the form of a

relatively sizeable organization on the ground.

3. Including only parties for which time-series data are available.4. In some cases, the sale of party property (particularly real estate) may account for part

of their ‘other’ sources of income. In the early 1990s, for example, the Hungarian Demo-

cratic Forum (MDF) and FIDESZ were involved in the illicit sales of their party head-

quarters, which had been donated state property to newly emerging parties at the time

of the transition.

5. For the Portuguese case, it should be noted that the figures presented here refer to elec-

tion campaigns only and that the dependence on public money for the financing of the

routine operational activities of political parties is, with the exception of the Communist

Party, equivalent to that of their Spanish counterparts (see Biezen 2000a). Furthermore,

even for the financing of elections, the role of the state in Portugal appears to be of increasing importance. A comparison of the 1995 and 2002 elections clearly shows an

increase in importance of state subventions (from 10 to 46.1%), while private contribu-

tions declined from 50.1 to 26.4%.

6. Unlike relatively familiar Southern European cases such as the disintegration of the

Spanish UCD only a few years after its creation (see Hopkin 1999), examples of party

ruptures in East-Central Europe in which the person of the party leader played an impor-

tant, if not crucial role, are relatively ill-documented. However, examples are neither

less infrequent nor insignificant, and include the collapse and ultimate disappearance

from the parliamentary scene of the Hungarian Christian Democrats (KDNP), the virtual

breakdown of the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF), the schism within the CzechCivic Democratic Party (ODS) that resulted in the establishment of the Freedom

Union (US), or the disputes that continue to plague the Hungarian Smallholder’s Party

(FKGP).

C ˇ C ˇ

y¢

ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 25/28

171

References

Aldrich, J.H. (1995). Why parties? The origin and transformation of political parties in America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Andeweg, R.B. (1996). Elite-mass linkages in Europe: Legitimacy crisis or party crisis? InJ. Hayward (ed.), Elitism, populism and European politics. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp.

143–163.

Balász, M. & Enyedi, Z. (1996). Hungarian case studies: The Alliance of Free Democrats

and the Alliance of Young Democrats. In P.G. Lewis (ed.), Party structure and organi-zation in East-Central Europe. Aldershot: Edward Elgar, pp. 43–65.

Bartolini, S. (2000). The political mobilization of the European left, 1860–1980: The classcleavage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bartolini, S. & Mair, P. (2001). Challenges to contemporary political parties. In L. Diamond

& R. Gunther (eds), Political parties and democracy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins

University, pp. 327–343.

Beyme, K. von (1996). Party leadership and change in party systems: Towards a postmod-

ern party state. Government and Opposition 31(2): 135–159.

Biezen, I. van (1998). Building party organisations and the relevance of past models: The

communist and socialist parties in Spain and Portugal. West European Politics 21(2):

32–62.

Biezen, I. van (2000a). Party financing in new democracies: Spain and Portugal. Party Poli-tics 6(3): 329–342.

Biezen, I. van (2000b). On the internal balance of party power: Party organizations in new

democracies. Party Politics 6(4): 395–417.Biezen, I. van (2003). Political parties in new democracies: Party organization in Southernand East-Central Europe. London/New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bowler, S., Farrell, D.M. & Katz, R.S. (1999). Party cohesion, party discipline and parlia-

ments. In S. Bowler, D.M. Farrell & R.S. Katz (eds), Party discipline and parliamentary government . Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, pp. 3–22.

Castillo, P. del (1989). Financing of Spanish political parties. In H.E. Alexander (ed.), Com- parative political finance in the 1980s. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.

172–199.

Coppedge, M. (2001). Political Darwinism in Latin America’s lost decade. In L. Diamond

& R. Gunther (eds), Political parties and democracy. Baltimore, MD: Johns HopkinsUniversity, pp. 173–205.

Daalder,H. (2001). The rise of parties in Western democracies. In L. Diamond & R. Gunther

(eds), Political parties and democracy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University, pp.

40–51.

Dalton, R.J. & Wattenberg, M.P. (eds) (2000). Parties without partisans: Political change inadvanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deschouwer, K. (1994). The decline of consociationalism and the reluctant modernization

of Belgian mass parties. In R.S. Katz & P. Mair (eds), How parties organize: Change andadaptation in party organizations in Western democracies. London: Sage, pp. 80–108.

Diamandouros, P.N. & Gunther, R. (eds) (2001). Parties, politics and democracy in the newSouthern Europe. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Diamond, L. & Gunther, R. (eds) (2001). Political parties and democracy. Baltimore, MD:

Johns Hopkins University Press.

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 26/28

172

Enyedi, Z. (1996). Organizing a subcultural party in Eastern Europe: The case of the

Hungarian Christian Democrats. Party Politics 2(3): 377–396.

Epstein, L. (1980). Political parties in Western democracies. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction

Books.

Gallagher, M. (1988). Conclusion. In M. Gallagher & M. Marsh (eds), Candidate selectionin comparative perspective: The secret garden of politics. London: Sage, pp. 236–283.

Gillespie, R. (1990). The break-up of the ‘socialist family’: Party-union relations in Spain,

1982–1989. West European Politics 13(1): 47–62.

Gunther, R., Montero, J.R. & Linz, J.J. (eds) (2002). Political parties: Old concepts and newchallenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harmel, R. (2002). Explaining organizational change: Competing explanations? In K.R.

Luther & F. Müller-Rommel (eds), Political challenges in the new Europe: Political andanalytical challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 119–142.

Harmel, R. & Svåsand, L. (1993). Party leadership and party institutionalisation: Three

phases of development. West European Politics 16(2): 67–88.Heidar, K. & Koole, R. (eds) (2000). Parliamentary party groups in European democracies.

London: Routledge.

Hopkin, J. (1999). Party formation and democratic transition in Spain: The creation and col-lapse of the Union of the Democratic Centre. London: Macmillan.

Hopkin, J. (2001). Bringing the members back in? Democratising candidate selection in

Britain and Spain. Party Politics 7 (3): 343–361.

Horváth, T.H. (ed.) (2000). Decentralization: Experiments and reforms. Budapest: Open

Society Institute.

Ikstens, J. et al. (2002). Political finance in Central Eastern Europe:An interim report. Öster-reichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 1: 21–39.

Kalyvas, S. (1996). The rise of Christian Democracy in Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univer-

sity Press.

Karl, T. (1990). Dilemmas of democratization in Latin America. Comparative Politics 23(1):

1–21.

Katz, R.S. (1990). Party as linkage: A vestigial function? European Journal of Political Research 18(2): 143–161.

Katz, R.S. (2002). The internal life of parties. In K.R. Luther & F. Müller-Rommel (eds),

Political challenges in the new Europe: Political and analytical challenges. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, pp. 87–118.Katz, R.S. & Mair, P. (1993). The evolution of party organizations in Europe: Three faces of

party organization. American Review of Politics 14: 593–617.

Katz, R.S. & Mair, P. (1995). Changing models of party organization and party democracy:

The emergence of the cartel party. Party Politics 1(1): 5–28.

Katz, R.S. et al. (1992). The membership of political parties in European democracies,

1960–1990. European Journal of Political Research 22: 329–345.

Kirchheimer, O. (1966). The transformation of West European party systems. In J. LaPalom-

bara & M. Weiner (eds), Political parties and political development . Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, pp. 177–200.

Kitschelt, H. (2001). Divergent paths of postcommunist democracies. In L. Diamond & R.Gunther (eds), Political parties and democracy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Univer-

sity, pp. 299–323.

Kopeck , P. (1995). Developing party organizations in East-Central Europe: What type of

party is likely to emerge? Party Politics 1(4): 515–534.

y¢

ingrid van biezen

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 27/28

173

Kosteleck , T. (2002). Political parties after communism: Developments in East-Central Europe. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Krouwel, A. (1999). The Catch-all Party in Western Europe: A Study in Arrested Develop-

ment. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam.

LaPalombara, J. & Weiner, M. (1966). The origin and development of political parties. In J.LaPalombara & M. Weiner (eds), Political parties and political development . Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 3–42.

Lewis, P.G. (1998). Party funding in post-communist East-Central Europe. In P. Burnell &

A. Ware (eds), Funding democratization. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp.

137–157.

Lipset, S.M. & Rokkan, S. (1967). Cleavage structures, party systems and voter alignments:

An introduction. In S.M. Lipset & S. Rokkan (eds), Party systems and voter alignments:Cross-national perspectives. New York: Free Press, pp. 1–63.

Luther, K.R. & Müller-Rommel,F. (eds) (2002), Political challenges in the new Europe: Polit-

ical and analytical challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Machos, C. (1999). A Magyar Pártok Szervezeti Struktúrájának Vázlatai [Main

features of the organizational structures of Hungarian parties] (Budapest Papers

on Democratic Transition 63). Budapest: Hungarian Centre for Democracy

Studies.

Magyar, B. (1992). The liberal paradox and the Alliance of Free Democrats. Liberal Voice:Newsletter of the Alliance of Free Democrats 1(1): 7–9.

Mair, P. (1990). The electoral payoffs of fission and fusion. British Journal of Political Science20: 131–142.

Mair, P. (1997). Party system change: Approaches and interpretations. Oxford: Clarendon

Press.

Mair, P. & Biezen, I. van (2001). Party membership in twenty European democracies,

1980–2000. Party Politics 7(1): 5–21.

Moser, R.G. (1999). Independents and party formation: Elite partisanship as an intervening

variable in Russian politics. Comparative Politics 31(2): 147–165.

Nassmacher, K.-H. (1989). Structure and impact of public subsidies to political parties in

Europe: The examples of Austria, Italy, Sweden and West Germany. In H.E. Alexander

(ed.), Comparative political finance in the 1980s. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, pp. 236–267.

Padgett, S. (1996). Parties in post-communist society:The German case. In P.G. Lewis (ed.),Party structure and organization in East-Central Europe. Aldershot: Edward Elgar, pp.

163–186.

Panebianco, A. (1988). Political parties: Organization and power . Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Pasquino, G. (2001). The new campaign politics in Southern Europe. In P.N. Diamandouros

& R. Gunther (eds) (2001). Parties, politics and democracy in the new Southern Europe.

Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 183–223.

Pierre, J., Svåsand, L. & Widfeldt, A. (2000). State subsidies to political parties: Confronting

rhetoric with reality. West European Politics 23(3): 1–24.

Rokkan, S. (1970). Citizens, elections, parties: Approaches to the comparative study of the processes of development . Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Sartori, G. (1968). The sociology of parties: A critical review. In O. Stammer (ed.), Party systems, party organisations and the politics of new masses. Berlin: Institut für Politische

Wissenschaft an der Freien Universität, pp. 1–25.

y¢

on the theory and practice of party formation and adaptation

© European Consortium for Political Research 2005

8/7/2019 Van Biezen EJPR2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/van-biezen-ejpr2005 28/28

174

Sartori, G. (1994). Comparative constitutional engineering: An inquiry into structures, incen-tives and outcomes. London: Macmillan.

Scarrow, S.E. (1996). Parties and their members: Organizing for victory in Britain andGermany. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schöpflin, G. (1993). Politics in Eastern Europe, 1945–1992. Oxford: Blackwell.Smith, G. (1993). Transitions to liberal democracy. In S. Whitefield (ed.), The new institu-

tional architecture of Eastern Europe. London: Macmillan, pp. 1–13.

Staniszkis, J. (1991). The dynamics of the breakthrough in Eastern Europe: The Polish expe-rience. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Szczerbiak, A. (2001). Poles together? The emergence and development of political parties in post-communist Poland. Budapest: Central European University.