Paper 2_Correcte

-

Upload

rogerio-c-correa -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of Paper 2_Correcte

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

1/14

HUMBOLDT UNIVERSITT ZU BERLIN

Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultt

The Financial Crisis and the Regulation of Financial Institutions

How Debt Can End A Debt-Originated Depression:

A Paul Krugmans View on the MinskysInstabilityHypothesis, the Danger of Austerity and the Euro Penalty.

Name: Pinto Maciel

Surname: Denis Augusto

Student Nr.: 505471

Professor: Gary Cohen

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

2/14

1

1. ObjectiveIn this paper, I will first firstly explain how high levels of debt in the private sector can

lead to an economic slump according to Minskys Instability Hypothesis. Then, based on

Paul Krugmans lessons, I briefly discuss why the government should step in and

increase its spending in order to stimulate the economy.After that,I will then argue that

the idea of aAusterity is a dangerous one, because it hinders action that could potential

minimize damage of the recessionthe actions that would minimize the recession

damages. Finally,I will demonstrate how a single currency makes recovery harder for

some European countries by limiting government action.

2. IntroductionThe origin of business cycles is one of the most important questions in macroeconomic

theory. The emergence of a boom followed by a bust in an economy has been recognized

as a constant in capitalist systems by almost all economists. However, iIdentifying,

however,the causes that unleash the bust is a great source of disagreement between the

schools of economic thought.

Following the burst of the 2007 housing bubble, the world experienced the deepest

economic crisis since the Great Depression. The so-called Great Recession was

responsible not only for a majorgreat slow-down of the global economic activity and

caused a , but also for the resurgence of the a great debate on economic theory. Even

well-establishedknowneconomists were puzzled bywiththe recession. Not long before

August 2007, many economists seemed fairly had considerable certainty that never

before hadthe economic system had never before been as safe and stable ound as it was

at theattime. Among these was the former president of the Federal Reserve Bank, Alan

Greenspan, the former president of the Federal Reserve Bank and then considered by

many as one of the best FED Presidents ever, was among them. All of this confidence

was mainly due to the FEDs rapid and successful response to previous crises such as the

dot-com bubble ofin the late 90s. Moreover, new financial instruments, whose

development was made possible only by the series of deregulation acts (supported by

Greenspan), played an important role in the build-up of such confidence. These

instruments were supposed to guarantee the soundness and stability of the whole

financial system,by transferring risks to actors who were more able and willing to bear

them. As pointed out by Paul Krugman in his New York Times article How Did

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

3/14

2

Economists Get It So Wrong?1, many outstanding economists were pretty much sure

about the stable situation of the economic theory before the shock caused by the crisis.

Olivier Blanchard of M.I.T., now the chief economist at the International Monetary Fund,declared that the state of macro is good. The battles of yesteryear, he said, were over, and

there had been a broad convergence of vision. And in the real world, economists believedthey had things under control: the central problem of depression -prevention has beensolved, declared Robert Lucas of the University of Chicago in his 2003 presidential address to

the American Economic Association. In 2004, Ben Bernanke, a former Princeton professorwho is now the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, celebrated the Great Moderation ineconomic performance over the previous two decades, which he attributed in part toimproved economic policy making.

In sum, everything seemed to be perfect, but it wasntsummary, the economic stability

was little more than an illusion.

3.

MinskysInstability Hypothesis

By the end of 2007 the American economy began to falterstarted to melt down, and,

along with it, the ideas of a Washington University professor,Hyman Minsky,whose way

of thinking wasnt very popular during his lifetime, experienced a comebackresurged.

Hyman Minsky tried to explain economic downturns in relation to the debt relating it to

the indebtedness level of the economy as a whole. The Minskys Financial Instability

Hypothesis links high leverage rates to the instability of the financial system, which

ultimately can lead to an economic slump. The theory goes as follows:

Debt,along with itsrelated concept credit,was an important human invention becauseit permitted the flow of capital between economic actors and resulted inthe resulting

better allocation of resources over time. However, being highly leveraged or, in other

words, having a big amount of debt relative to own assets leads to a state of

vulnerability. During good times having highbiglevels of debt is actually no big deal.

The problems that gocomingalong with debtindebtednessappear onlyexactlywhen one

facesaneconomic hardship. The pros and cons of incurring in debt is well explained by

Anat Admati and Matin Hellwig in their book The Bankers New Clothes:

Borrowing creates leverage: by borrowing, individuals and businesses can makeinvestments that are larger than they can afford on their own right away. This leveragecreates opportunities for the borrower, but it also magnifies the borrower's risk. Theborrower makes promises to pay lenders specific amounts at given times in the future andgets to keep everything that is left after these promised debt payments. On the upside, if theinvestments turn out well, the leverage magnifies the borrower's profit. On the downside,

1Krugman, Paul R. How Did Economists Get It So Wrong? . The New York Times, Sep. 2, 2009.http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.Oct. 10, 2013.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 -

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

4/14

3

however, if the investments do not return enough, the leverage magnifies the losses. Themore one borrows, the greater this danger. 2

Until this point, weve limited ourselves to a microanalysis firms and individuals

singularly consideredbutnot the economy as whole. Lets now jump to the macro level

of analysis in order to understand the consequences of debtindebtedness. It should be

pretty clear that a family who has financed 90% of its house is much more vulnerable to

an interest rate fluctuation than one that has made a 50% down payment (micro-level).

What may be not so obvious, however, is that a wholly indebted economy turns out to

be more vulnerable to financial crises (macro-level). As Paul Krugman explains, high

levels of debt leave the economy vulnerable to a sort of death spiral in which the very

efforts of debtors to deleverage, to reduce their debt, create an environment that

makes their debt problems even worse.3

Supposethe following situation: inan economy where households and businesses keep

high levels of debtare relatively highly indebted, here an economic downturn wouldill

lead the debtors to minimize the amount of money they owe. They can either sell their

assets or cut spending, using the extra money to pay their debts. The problem emerges,

when the economy as a whole goes under water, causing too many people to take these

actions at the same time. If a great number of people go to the market in order to sell

their assets lets say real estatehouses the major effect of this common action is a

substantive drop in home prices. According tos Paul Krugman says, the efforts of the

homeowners are self-defeating. While theyre trying to get rid of their assets, adeflationary process takes place. The larger offer leads to the inevitable consequence of

plummeting prices. Thats why, even as the nominal debt is being reduced, the real

burden of it increases along with the purchasing power of a dollar. To explain this self-

reinforcing process Irving Fisher coined the expression that, which, though imprecise,

expresses the essential truth: The more the debtors pay, the more they owe.

A further consequence of this scenario is the situation Paul Krugman described as that

in which debtors cant spend, and creditors wont spend. Furthermore, according to

the same author, this state of affairs must can not only be observed in the private sector

(the households of highly indebted counties in the U.S. cut spending drastically, while

those of low-debt counties just kept spending as much as they did before), but also in

the public sector (within the European Union the more troubled countries are forced to

go into very strict austerity programs and countries that have a relatively sound

2Admati, Anat; Hellwig, Martin F. The Bankers' New Clothes: What's Wrong with Bankingand what to Do about it. (Princeton University Press: Princeton, 2013), pg. 17.3Krugman, Paul R. End This Depression Now!. (W.W. Norton: New York, 2012), pg. 44.

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

5/14

4

economy are trying to reduce spending as well). The obvious result o f this f all that is a

decline in aggregate demand, which, inby its turn, leads to lower output and higher

unemployment.

Nevertheless, one may still be puzzled and question: how did the economy get to such a

high level of indebtedness debt? How could lenders not have noticed how risky the

loans made were? And how could debtors get in such troubles taking risks they couldnt

bear?

An economy with low debt levels is usually not subject to major economic shocks.

According to the argument made on previous paragraphsThus, these shocks wouldnt

have a great impact because no great amount of debt should be paid, the run to markets

wouldnt occur and, in consequence, the aforealready mentioned debt spiral wouldnt

take place. The problem is, Hyman Minsky argued, that the overall perception about the

real risks of lending and borrowing may decline over time and the memory ofaboutbad

time momentsfades away, which may have occurred in the past, just vanishes.

Thisathappens exactly because a low-debt economy and the resulting stability of the

financial system gives economic actors the feeling of safety and confidence. When the

economy is doing well, leveraging might almost always be a good deal, even for those

who cant put any money downat the time of borrowing. Back to the example of the

housing market: if someone buys a house with no down payment, he will have a

substantial equity stake as the price rises and time goes by. The equity results

specifically from the difference between the actual price of the house andthe remaining

debt. The lenders, in turnon their turn, take lessowerrisks. If the borrower cant keep

paying the mortgage, the solution is to sell the house and pay the remaining debt.

Therefore, gGiven the rising prices, defaults are, therefore, few and far betweenreally

seldom because the mortgages face value will always be lower than the actual home

price.

The general feeling of safety and the lowering of the lending standards set the stage for

what the economist Paul McCulley called the Minsky Moment. Paul Krugman describesthis moment and its consequences very well:

Once debt levels are high enough, anything can trigger the Minsky momenta run-of-the-mill recession, the popping of a housing bubble, and so on. The immediate cause hardlymatters; the important thing is that lenders rediscover the risks of debt, debtors are forcedto start deleveraging, and Fishers debt-deflation spiral begins.4

4Krugman, Paul R. op. cit., pg. 48

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

6/14

5

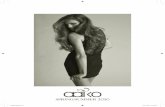

If you look at the data, the Minskys Instability Hypothesis seems highlyreallyplausible.

Not only did high levels of indebtedness precede the Great Depression and the Great

Recession, but one can also see an upswing inuprising of the debt-to-GDP ratio5. The

second symptom the high slope of the graphic line even after 1929 - is not related to a

growth in debt, but to a rapid slumpsinkinginofthe GDP. That phenomenon cannot be

observed after 2007, mostly because the governments response in the past few years

was more energetic in comparison to the past inertia, which didnt let the GDP sink as it

did before.

The Fall and Rise of Household Debt6

What weve seen until now is that a highly indebted economy faces the constant danger

of a meltdown since leverage is closely related to the instability of the financial system.

Now we must ask ourselvesBut its time to ask: whatichis thebestway out of the crisis?

If debt leads to economic instability, the solution for a debt crisis must be to cut

spending and to save money; one could argue that the roots of the instability should be

destroyed, one could argue. The answer, however, is not that obvious. In fact, what helps

the economy make its way out of the debt-originated slump is not to reduce spending

and to diminish debt levels. What a depressed economy really needs is more debt. But,

this time, not private debt. Instead, the remedy the Depression Economics prescribes to

such a situation is the increase in public spending. The wWhy and the how of this will be

my focus in this should be done is what will be explained on the following pages.

5A measure of a country's federal debt in relation to its gross domestic product (GDP). Bycomparing what a country owes to what it produces, the debt-to-GDP ratio indicates thecountry's ability to pay back its debt.6I took the graphic from Paul Krugmans book End This Depression Now! . Source: HistoricalStatistics of the United States and Federal Reserve Board. Notice that the data is not allcompatible over time (one set of data runs from 1916 to 1976 and the other from 1950 up to thepresent). For the argument made here, however, this divergence is not important.

Debtas

ofGDP

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

7/14

6

4. Depression EconomicsHigh unemployment and a negative growth rate:.tThese are the major problems of an

economic recession. But why does all of thisthathappen to an economy that seemed to

be perfectly healthy months before the meltdown began? In fact, resources and

knowledge are still there to be used. Neither a natural disaster hindered the

economyThe economy was not hindered by a natural disaster, nor byis therea shortage

of any raw material. The real cause of high unemployment and the low economic output

is the insufficient aggregate demand. Due to the loss of confidence caused by the crash of

the financial system, consumers are unwilling to spend. As demand decreases,

businesses must slow down productionand lay off firingworkers. In turn, with the rise

of unemployment, confidencein future household incomes decreases, of the households

in the future deepens further leading to an even smaller demand.

That is exactly what Keynes called the paradox of thrift. This paradox states that what

seems reasonable for a household individually may cause great harm to the economy as

a whole. In more specific terms: if everyone tries to save more in a depressed economy,

this increased desire to save will not lead to higher investment, which would enhance

wealth in the future. Instead, the result of this widespread effort of saving money is that

income declines and the economy shrinks. After all, your spending is my income, and

my spending is your income7. In attempting to save more, households and businesses

end up shrinking present and future output in aggregate.

If households and businesses are not able to get out of this self-reinforcing downward

spiral, who should assume the task of breaking the circularity of this demand-shrinking

vicious cycle? The answer is: government. It is the most suited economic actor for this

jobto do this job.

Government can fight a recessionbasicallyin two ways: inflating the monetary system

or increasing public spending. Lets explain briefly examine these two mechanisms.

First: inflating the monetary system (which is pretty much the same as increasing the

money supply or, in even simpler terms, printing money) results ultimately in a lowerinterest rate. On one hand, it reduces the cost of borrowing causing consumption to be

cheaper; on the other hand, theresa rise in inflation which in turn devalues the money

over time and makes saving less interesting. Thus, by acting on the monetary system,

the government induces the households and businesses to increase spending. That

means the government will increase the aggregate demand only indirectly.

7Krugman, Paul R. op. cit., pg. 28

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

8/14

7

The government, however, can also act directly to soften and solve the problem of

insufficient demand. Carrying out public enterprise,Funding public works, such as

bridges and roads, is another possibility to reduce unemployment and increase demand.

In this case, the government itself wouldill buy the required goods and raw materials

and hire the workforce that would otherwise be unemployed. The money injected in the

economy would thenill be spent either by the newly employed workforce or by the

government suppliers, stimulating the whole economy. According to Keynes lessons,

the main point is the money circulation in the economy. The government must ensure

that, even if not in an usual way:this circulation:

If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths indisused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it toprivate enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right

to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), thereneed be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income ofthe community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than itactually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there arepolitical and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing. 8

However, eEvery economic decision carries with it a trade-off, however. Its for no other

reason that economics is often called the dismal science. In the case were dealing with,

Iits not different in our case. Although it seems clear that the increase in public

spending prevents aggregate demand from falling sharply, it comes with a cost. The

money used by the government to finance public spending can either be raised through

taxation or by borrowing. As taxation charges the economy with a heavy deadweight

loss, raising money on financial markets (building up debt) is the most commonly-

mostly the chosen option. Yet, the borrowed money must be repaid in the future and

here we come to the problem of debt, which will be dealt with in the next pages.

5. Public DebtIt may sound quite paradoxical to say that the way out of a debt-originated crisis lies in

creating more debt. Still, this is the right answerAnd yet we see this as the correct

answer. To defend this point, of view let usI will begin start by tackling its critiques,

which may provide us with an overview of the pros and cons this idea implicates.Analyzing and refuting the criticism against expansionary policy is actually the best way

to defend a Keynesian response to the crisis. Its prettyc much clear that a government

is able to stimulate an economy. Moreover, whether an increase in government

spending lowers the unemployment rate is no questiont object of questions. The

epicenter of economic debate is whether the side effects of an expansionary and

8KEYNES, John Maynard. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. (TheMacMillan Press LTD: London, 1973), pg. 129

Comment [DM1]: Adicionar notaexplicando o conceito?

Comment [D2]:

Comment [D3]: Yes, please explain!

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

9/14

8

interventionist policy would outweigh the benefits of reducing unemployment and

increasing growth. Put in simple terms: at which cost can we stimulate our economy?

5.1. Fiscal Policy Against Monetary Policy?The first point that should be tackled is the statement about the supposedly irrational

opposition between fiscal and monetary policy. In a depressed economy the central

bank must lower the interest in order to stimulate consumption thats the monetary

policy. On the other hand, Keynesianism prescribes a government intervention by

borrowing in the market to finance public spending. Yet, as the government goes to the

capital market and borrows, the demand for money will increase, which ultimately

would lead to a higher interest rate. If things were like this, the obvious conclusion is

that government is acting in a paradoxical way. While the central bank tries to lower

interest rates, governmental borrowings in financial markets will increase money

demand and, thus, the interest rates.

Even though this statement seems plausible at first glancesight, it doesnt holdtrue in a

depressed economy. When we find ourselves in an economic slump, there are more

savings available than there are investors willing to use that money. Even with an

interest rate near zero, there will still be extra savings waiting for an opportunity to be

invested. Theres an excess of money supply and the government borrowing would

absorb that. As Paul Krugman clearly explains:

In effect, we have an incipient excess supply of savings even at a zero interest rate. Andthats our problem.

So what does government borrowing do? It gives some of those excess savings a place togo and in the process expands overall demand, and hence GDP. It does NOT crowd outprivate spending, at least not until the excess supply of savings has been sopped up, which isthe same thing as saying not until the economy has escaped from the liquidity trap. 9

Therefore,by borrowing money, the government would directly compete with private

enterprises. On the contrary, it wouldill invest an amount of money that, which

otherwise would be useless.

5.2. Overall DebtEven though in a depressed economy the government borrowing wont increase the

interest rate, the overall debt burden can still be a problem. First of all, investors can put

the solvency of highly indebted countries into question. As a result of this there is a loss

9Krugman, Paul R, Liquidity preference, loanable funds, and Niall Ferguson (wonkish) . TheNew York Times, May 2, 2009. http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/ . July 12, 2013.

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/ -

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

10/14

9

of confidence in public finance, causing interest rates to rise because investors consider

it riskier to put their money in these highly indebted countries. Ultimately, the

incapacity to borrow at reasonable interest rates may lead a country to default. This is of

course a terrible scenario since the government wouldnnt be able to fulfill its role

properly. In the end, those who mostly depend on the state (normally the most in need)

will suffer from the governments incapacity to finance its activities.

This is exactly the trade-off policy makers face. Although public spending is clearly the

best way to drivetakethe economy out of atheslump, the debt level that the government

maycan incur in is not unlimited. Too much debt is dangerous. Yet to cut spending

before the ideal point means to sacrifice the unemployed and to leave the economy in a

recession. Defining at which moment the debt turns out to be excessive is the question

economists must deal with. In fact, they are presently grappling with this questionatswhat theyre doing right now. IAnd, in doing so, some of them have , particularly in

Europe, started to argue plead for more austerity. The argumenti was that due to high

debt levels Europeanlevels of debt, Europeancountries wereteetering on atthe edge of

a debt crisis. Is tightening public spending really the best solution for European

problems? Are the supposedly high levels of public debt the origin of all trouble in

Europe?

6. AusterityIn the beginnings of theAt the start of thecrisis, it was obviousalmostfor everyone that

an expansionary policy should be adopted. But then the debt crisis struck Greece. Anti-

Keynesians pointed out the dangers of a highly- indebted economy and advocated it was

already time to take policy measures that would ensure austerity: cut spending and

raise taxes. The Greek financial crisis the soaring interest rates faced by the Greeks

created the illusion that a great part of the European nations problems resulted because

of high levels of debt.

The Hellenization of Europe i.e. the tendency to treat every European country with

financial problems as Greece ultimately led to austerity policies10. The EuropeanCentral Bank, responsible for supporting troubled economies, made financial aids

conditional on cutting budgetsupon budget cutsand deficits loweringlowering deficits.

Despite saving the bank system fromof a massive bankruptcy, those measures had the

effect of deepening the economic slump eventfurther in an already depressed economy.

10See, for example: The Economist, Spains bail-out: Insuficiente, Jun 16th 2012.http://www.economist.com/node/21556938.

http://www.economist.com/node/21556938http://www.economist.com/node/21556938http://www.economist.com/node/21556938 -

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

11/14

10

Ultimately, the policies, themselveswhich were targeted at increasing investors

confidence by reducing public debt, were responsible for raising the debt-to-GDP ratio,

as can be seen in the graph on the next page. Of course, what led to an impressive

increase in this ratio was the considerable economic slowdown experienced by these

countries. The debt was in fact reduced, but not in the same proportion as the economic

slowdown. Thus, the negative effects in the economy resulting from such measures have

clearly overcome the potential gains of greater confidence.

From the point of view of economic theory, such a result is to should even be expected.

Krugman differentiates cutting spending in a depressed economy and in an economy

near full employment. This basic distinction explains the lack of success related to

austerity policies:

Finally, even if one took warnings about a looming debt crisis seriously, it was far fromclear that immediate fiscal austerityspending cuts and tax hikes when the economy wasalready deeply depressedwould help ward that crisis off. Its one thing to cut spending orraise taxes when the economy is fairly close to full employment, and the central bank israising rates to head off the risk of inflation. In that situation, spending cuts need not depressthe economy, because the central bank can offset their depressing effect by cutting, or at leastnot raising, interest rates. If the economy is deeply depressed, however, and interest rates are

already near zero, spending cuts cant be offset. So they d epress the economy furtherandthis reduces revenues, wiping out at least part of the attempted deficit reduction .11

Not only the relation between debt and growth was affected. Even the major promise of

the austerity program couldnt be heldwas not fulfilled: confidence didnt rise. The

interest rate for the PIIGSs (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain) bonds soared,

despite all budget cuts, as Mark Blyth pointed out:

11Krugman, Paul R. End This Depression Now!. (W.W. Norton: New York, 2012), pg. 194

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

12/14

11

So PIIGS cut their budgets and as their economies shrank, their debt loads got bigger notsmaller, and unsurprisingly, their interest payments shot up. Portuguese net debt to GDPincreased from 62 percent in 2006 to 108 percent in 2012, while the interest that pays forPortugals ten-year bonds went from 4.5 percent in May 2009 to 14.7 percent in January

2012. Irelands net debt-to-GDP ratio of 24.8 percent in 2007 rose to 106.4 percent in 2012,while its ten-year bonds went from 4 percent in 2007 to a peak of 14 percent in 2011. Theposter child of the Eurozone crisis and austerity policy, Greece saw its debt to GDP rise from106 percent in 2007 to 170 percent in 2012 despite successive rounds of austerity cuts andbondholders taking a 75 percent loss on their holdings in 2011. Greeces ten -year bondcurrently pays 13 percent, down from a high of 18.5 percent in November 2012.12

6.1.The Euro Penalty

All the data presented up to now is still not enough to once and for all defeat austerity

advocates. They still have the benefit of the doubt. It could be argued that: if the

austerity measures hadnt been adopted, things would be even worse and investors

could have completely abandoned the idea of lending money to countries in trouble.

After all, money borrowed at high interest rates is better than borrowing no money at

all.

In order to deal with these pro-austerity arguments and finally identify the real problem

in some of the Euro-Zone countries, it may be necessary to take a closer look at other

countries in a similar situations outside the Euro-Zone, which, however, dont have the

Euro as their currency.

Lets compare Great Britain with Spain. The former has a much a way higher debt-to-

GDP ratio than the latter. Yet the British 10-year bond yield has been below 4% over the

past 10 years,while the Spanish has never gone under the same 4%, as can been seen in

graph on the next page. If the debt level is directly related to investors confidence, we

should expect Spains capital cost to be lower. But that isnt the case. Moreover, Japan,

whose public debt has recently exceeded 1 quadrillion ($16.74 trillion)13, but still has

0.72% yield on its 10 year bonds, is also an example proving the relation between debt

and interest levels is not always true.

The most convincing reason for why Spain has faced an imminent threat of a financial

crisis is the fact that theecountry doesnt have its own currency. Firstly, one should

notice that, if Spain could print its own money and control the levels of inflation, it

would be able to reduce the real burden of its public debt by imposing a higher inflation

than the actual Euro-zones. Secondly, controlling its own currency practically

12Mark Blyth .Austerity: the history of a dangerous idea . (Oxford University Press: New York,2013), pg. 4.13Phillps, Matt. With a quadrillion in debt, theres only one way out for Japan . Quartz, Aug12, 2013. http://qz.com/113948/with-a-quadrillion-in-debt-theres-only-one-way-out-for-japan/. Aug 27, 2013.

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

13/14

12

eliminates the risk of a freeze-up of liquidity. To understand this idea, one should keepin mind that public debts must often be rolled over. As the time comes when some the

debts must be paid, governments normally issue more bonds, using the raised money to

pay debtors whose credits are due. However, it can happenIt can happen, however,that

investors, for whateversomereason, refuse to lend the government more money. In this

case, even solvent governments run out of cash and are forced into default.

If a country goes through such a situation, it can avoid default on its debts by printing

money to pay them. The Euro-Zone countries, however, dont have the possibility of

rolling the public debt over by creating money out of thin airprinting money, because

theyare re all under the European Central Banks jurisdiction. OneThissingle fact gives

rise to the possibility of a self-fulfilling crisis: investors may fear a freeze-up of liquidity

and for this reason they wont lend the government any money, turning the feared

scenario into reality.

British and Spanish Debt-to-GDP Ratio and 10-

Year Bond Yield

-

8/14/2019 Paper 2_Correcte

14/14

13

Paul Krugman has created the term called the euro penalty to refer to the higher taxes

countries in theto Euro-Zoneeuro have to deal with. Also a clear example is the

difference of borrowing costs among Finland, Sweden and Denmark. Out of these three,

only Finland has adopted the euro, being the country facing the highest interest rates as

would be expected.

7. Conclusion8. References

8.1.Books

Admati, Anat; Hellwig, Martin F. The Bankers' New Clothes: What's Wrong withBanking and what to Do about it. (Princeton University Press: Princeton, 2013)

Blyth, Mark . Austerity: the history of a dangerous idea. (Oxford University Press:New York, 2013)

Keynes, John Maynard. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money .(The MacMillan Press LTD: London, 1973)

Krugman, Paul R. End This Depression Now!. (W.W. Norton: New York, 2012)

8.2.Articles and Newspaper

Minsky, Hyman P. The Financial Instability Hypothesis. Working Paper N. 74, May1992.

Krugman, Paul R. Liquidity preference, loanable funds, and Niall Ferguson(wonkish). The New York Times, May 2, 2009.http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/. July 12, 2013

Krugman, Paul R. How Did Economists Get It So Wrong? . The New York Times, Sep. 2,2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.Oct. 10, 2013.

Phillps, Matt. With a quadrillion in debt, theres only one way out for Japan. Quartz,Aug 12, 2013. http://qz.com/113948/with-a-quadrillion-in-debt-theres-only-one-way-out-for-japan/. Aug 27, 2013.

8.3.Interviews

FCIC staff audiotape of interview with Paul Krugman, Princeton University, Oct. 6, 2010.

http://fcic.law.stanford.edu/interviews/view/226 .

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0http://fcic.law.stanford.edu/interviews/view/226http://fcic.law.stanford.edu/interviews/view/226http://fcic.law.stanford.edu/interviews/view/226http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/