Brouwer Paper

-

Upload

juan-daniel-cid-hidalgo -

Category

Documents

-

view

245 -

download

6

Transcript of Brouwer Paper

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

1/20

Nick NortonJuly 2009

Characteristics Defining the Three Compositional Periods in

the Solo Guitar Music of Leo Brouwer

Introduction

Leo Brouwer (b. 1939, Havana) is widely considered to be the most

significant living composer of art music for the guitar.1

He is also the composer of

numerous film scores, operas, large-scale orchestral works, and chamber pieces, and

has worked in popular music and jazz. Numerous interpreters of his work have

divided his compositional output into three phases, and have titled and dated these

phases Nationalistic (1955 62), Avant Garde (1962 67, with some arguing

until 1980), and New Simplicity (1980 on).2

This paper will catalogue the characteristics of the musical language of each

phase, focusing solely on the solo guitar music to create a control group and limit

variation in the music that could be attributed to instrumentation or technology. I will

analyze music of each periods form, pitch usage (or Brouwers choice and

manipulation of harmonic and melodic material), and rhythm. In each section I will

first explain the common characteristics, and then a few examples of each will be

given. I will examine each period individually to illuminate the differences between

them, and the remaining characteristic similarities between the different phases can

then be considered as the underlying compositional tendencies that uniquely define

Brouwers music. These characteristics ultimately will serve to highlight the unique

status of Brouwers music as a fusion of elements usually thought oppose one another

dialectically, such as tradition and innovation, or community and independence.3

1

Clive Kronenberg, Guitar Composer Leo Brouwer: The Concept of a Universal

Language, Tempo 62, no. 245 (2008): 30.2

Victoria Eli Rodrguez, "Brouwer, Leo." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/04092.3Edward D. Latham, Binary Oppositions in Arnold WhittallsExploring Twentieth-Century

Music: Tradition and Innovation and Their Implications for Analysis,Music Theory Online

10 no. 3 (2004): table 1b.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

2/20

First Period Nationalistic, 1955 - 61

Form

Brouwers earliest works for solo guitar show a direct engagement with traditional

form. Fuga No. 1, from 1957, for example, makes no attempt to expand upon the

common understanding of fugue, perhaps except for allowing an extended episode (b.

38 44) before the coda (b. 35). Pieza Sin Titulo No. 1, also from 1957, uses a stark

ternary structure with a very short ending coda (b. 30 33). This ABA form,

immediately apprehensible to the listener, is also used in the next two numbered

Piezas Sin Titulos (1956/62), and in nine out of the ten pieces in his first two sets of

Estudios Sencillos (1960). While the music of this early period shows nothing

remarkable in the music itself with regards to form, this neo-classical preoccupation

has an explanation central to many other aspects of Brouwers composition of this

early phase.

From an early age Brouwer was a member of the Grupo de Renovacin

Musical, which was founded in Havana by the composer Jose Ardevol in 1942.

Ardevols purpose was to create a Cuban school of composers that could reach the

same degree of universality as found in other countries, and to achieve a universal

form of expression for Cuban composers without losing the innate qualities of Cuban

culture.4

Thus, the philosophy of the Grupo emphasized the cultivation of classical

forms and their employment in new works, and the mastering of musical techniques

found in more developed countries.5

As such, one could say that Brouwer intended the use of traditional form in his

early works as a mere vehicle, or a sort of transparent medium, for the expression of

his nationalist musical persona, which emerges in his harmonic and melodic material

4Paul Reed Century, The principles of pitch organization in Leo Brouwers atonal music for

guitar (PhD diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 1991), 7, cited in Kronenberg, 33.5

Kronenberg, 34.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

3/20

and Afro-Cuban rhythms. In this early usage of form Brouwers role as an

intermediary figure between community (the community of the European tradition)

and independence (that of Cuban music as existing outside of that tradition) comes

into focus.6

Pitch Material

Brouwers solo guitar music from the first period makes use of modal thematic

material inspired by traditional African ritual music, but sets this material in a

contemporary harmonic structure. Though usually tonal, Brouwers early harmony

often hinges on his use of highlighted minor-second dyads, tritones, and chromatic

coloring.7

Chords or sonorities based on diatonic clusters are common. His early

music sometimes makes simultaneous use of multiple tonal or modal centers, or rapid

changes of mode (or simultaneous use of multiple modes) based on the same pitch

center. (Estudio Sencillos #1, #6, Pieza Sin Titulo #1, #3). Numerous pieces are

governed by quite basic triadic harmony (Pieza Sin Titulo #1 3), though this often

occurs with added notes (Preludio), and is broken by surprising modulations (usually

through a common tone), while juxtaposed against changing modal melodies. These

features bring Brouwers harmonic language into the common practice of extended

tonality of the twentieth century, not dissimilar to that practiced by composers such as

Bartok or Stravinsky.

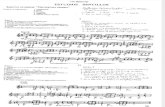

The first piece in hisEstudios Sencillos, a series of pieces aimed at students of

the guitar incrementally increasing in difficulty, provides a clear example of his

modal manipulation of African inspired melodies, as well as his attraction to pedal

points (ex. 1). The short and rapid melody in the bass begins by leaping up a minor

6Arnold Whittall,Exploring Twentieth Century Music: Tradition and Innovation

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 48 49.7

Kronenberg, 36.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

4/20

seventh from the guitars lowest E before peaking at the F# a third above that

(outlining a ninth) and winding back down through a C natural to B, firmly

establishing the mode of E Aeolian, especially when set with the inverted G and B

pedal on the open treble strings. The figure is immediately repeated (b. 3 4);

however this time the C natural rises to a C#, expressing E Dorian for a bar, before a

the melody begins to make rhythmic leaps between F natural and C, allowing the

modality to settle into E Phrygian (bolstered by the continuing G and B pedal) for a

few bars:

Example 1

In his early guitar pieces, Brouwer commonly uses pedal points in this way. In the

first two sets ofEstudios Sencillos, composed from 1959 61, he uses pedal points

beneath a changing harmony in eight of the ten pieces. In Fuga No. 1, Brouwer

quickly establishes the opening D as a pedal tone, and governs a large scale

background harmonic progression from D (I, bar 1) to A7 (V, b. 13) and back (b. 21).

When the A dominant seven harmony arrives in second inversion in bar 13, Brouwer

repeats the major second dyad between G and A in semiquavers, creating yet another

inverted pedal while the E in the bass begins a restatement of the theme in E Aeolian.

Here the inverted pedal simultaneously expresses the dominant key area and this

mode for the melody. At other times it is used as a tool for contrast, such as in bar 15,

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

5/20

when the repeated semiquavers rise through a series of chromatic transformations

while the E Aeolian melody remains constant.

As mentioned, Brouwers early guitar music often features chromatic

modulations to surprising new tonal keys. One clear example of this is the fifth piece

in Estudios Sencillos. The piece opens with a bare C major arpeggio, which then

descends through a series of tonal chords with a few chromatic passing tones, over a

pedal tone C. Early on (b. 5), he begins to raise the sixth scale degree to A sharp,

although this spelling appears to have more to do with clarity for performance than a

harmonic purpose, as it tends to sound as a lowered seventh (from the B natural

immediately preceding it), creating a C Mixolydian modality. Brouwer gradually

isolates the A sharp, however, as the other notes disappear (b. 9). It suddenly becomes

the fifth degree of a clear E flat major triad, followed by a modal triad built on its

dominant B flat (a D flat hinting at E flat Mixolydian), and decorated by a few

chromatic neighboring tones (b. 10). Brouwer uses similar technique to return to C

major to close the piece, as an apparently decorative B natural (part of a highlighted

minor-second dyad with B flat, spelled as an A sharp) becomes isolated and then is

filled in from below to become part of the dominant chord in C (b. 17 18).

Here again one can observe Brouwers position in the middle of an apparent

dialectic between tradition and innovation. On one side, his music pays tribute to

tradition, holding itself together through largely tonal means including the inherited

common practice usage of dominant chord tendencies to establish key. In a sense,

however, this inherited usage subverts itself, leading in its usual convincing way to

unexpected, highly unconventional (yet still tonally governed) key centers, achieving

complete chromaticism by tonal means within local movements (ex. 2).

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

6/20

Example 2

Rhythm

Brouwers early guitar music is full of Cuban dance rhythms, nested at various depths

between the foreground and background of the texture and often placed in

juxtaposition against a steady metric pulse. Two rhythmic groupings in particular are

especially prominent (ex. 3): the tresillo, or a syncopated three-note group, and the

cinquillo, a similarly syncopated group of five notes.8

Tresillo and common variations:

Cinquillo and common variations:

Example 3

One method that Brouwer uses to achieve the aforementioned aims of the Grupo de

Renovacin Musical is generous use of these rhythms in pieces based on inherited

traditional structures- especially when juxtaposed against a steady pulse, as one might

find in a Baroque dance suite. This also serves as another example of his synthesis of

8

Fernando Ortiz,La Africania de la Musica Folklorica de Cuba (Habana: Editora

Universitaria, 1965), cited in Kronenberg, 34.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

7/20

the Apollonian (community [European], tradition, stability) and Dionysian

(respectively: individuality [Cuban], innovation, instability) sides of the twentieth

century musical dialectic.9

Preludio, from 1956, is written in 6/8 time, but by the second bar a duplet has

already appeared, implying that when the 6/8 pulse is divided it can be heard as a

tresillo figure. Clive Kronenberg, a frequent commentator on Brouwers guitar music,

points out that at times in the piece 2/4 is implied, while 3/4 also features

periodically.10 The tresillo figure appears most prominently in bars 31 through 32,

and again in the accented four-note chords at bars 53 and 54, marking the beginning

of the brief coda, which also momentarily features this rhythm (ex. 4).

Bars 29 32:

Bars 51 54:

Coda:

Example 4

9

Latham, table 1a.10

Kronenberg, 38.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

8/20

Pieza Sin Titulo No. 1 (1956) uses a similar juxtaposition of syncopated rhythmic

groups against a steady pulse, but instead features the cinquillo rhythmic group

(although the tresillo can be found as well). In this case, however, he cleverly

conceals these rhythmic groups beneath the surface, or tactical, pulse of the piece.

Pieza Sin Titulo No. 1 maintains a 7/4 meter, which is periodically expressed through

its 3/4 and 4/4 subdivisions.11 A variation of the cinquillo appears in the opening

melodic pitches, but is offset by an extended duration of its final note before a

repetition, which cleanly hides the rhythm in the 7/4 meter.

Brouwer is often attracted to odd meters in his early guitar music. This can be

observed plainly in Estudios SencillosNos. 1 and 4, Tres Piezas Sin Titulos (which

include the aforementioned piece),Danza Del Altiplano, andElogio de La Danza, in

which the second movement rapidly alternates between 2/8, 3/8, and 4/8.

Second Period Avant Garde, 1961 (arguable) 1980

Toward the end of his early period (1959 1960) Brouwer traveled to New York to

spend a year studying composition at The Julliard School under Vincent Persichetti.

While there he came into contact with the work of Darius Milhaud, Lukas Foss, and

Paul Hindemith. The next year Brouwer attended the Warsaw Autumn Festival in

Poland and was present at the premiere of Pendereckis Threnody for the Victims of

Hiroshima. He also began to cultivate a relationship with Hans Werner Henze. These

experiences cemented his awareness of, interest in, and admiration for the avant-garde

techniques the most advanced contemporary composers of the day practiced.

Brouwers adoption of these techniques such as aleatoricism, the use of

extended instrumental technique, and the adoption of a nearly atonal harmonic

language, could be viewed as leap toward the innovation side of the twentieth-century

11

Kronenberg, 37.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

9/20

musical dichotomy, but this would be an oversimplification. One must keep in mind

the tenet of the Grupo de Renovacin Musicalthat seemingly guided his early musical

thought, that Cuban composers had to master the techniques being used in more

developed countries. In light of this, one can interpret Brouwers turn to the avant-

garde as an attempt to bring his music into alignment with the new tradition forming

in Europe and the United States. One might even cite this concept of a tradition of

innovation in reconsidering the divisions of the commonly accepted dialectical

understanding of composition in the twentieth-century.

While Brouwer quickly adopted European avant-garde techniques to his

compositions in other mediums (his Sonograma I for prepared piano was the first

aleatoric work from a Cuban composer and received a premiere at the Union of Cuban

Writers and Artists in 1961), it took significantly longer for these techniques to make

their way into his guitar music. The common understanding is that Brouwers avant-

garde period abruptly began in 1961, but the solo guitar piece Elogio de la Danza,

from 1964, exhibits- with the slight addition of a few extended techniques- all of the

characteristics of pieces from his early period and therefore refutes this notion.12 The

first guitar piece that fits squarely into his avant-garde style, Canticum, did not appear

until 1968, hinting that Brouwers transition into his second phase was more gradual

than is regularly assumed.

Form

The use of aleatoric or indeterminate form appears in the guitar music of Brouwers

avant-garde phase. In many cases the structures of pieces are left to the discretion of

the performer, in a sort of musical choose your own adventure. Tarantos, from

1974, is made up of seven numbered statements [enunciados], six lettered

12

Kim Nguyen Tran, The Emergence of Leo Brouwers Compositional Periods: The Guitar,

Experimental Leanings, New Simplicity (senior honors thesis, Dartmouth College, 2007), 30.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

10/20

redoubles [falsetas], and an ending [para final]. The performance instructions state

that the numbered statements are to go before and after each lettered redouble, and

separate the last redouble from the ending. Within this framework, the statements and

redoubles can be performed in any order, so long as none are repeated. Brouwer gives

the following example of structure in the performance instructions:

V B I A VI C III D VII E IV F II FINAL

Within each section all of the musical material is pre-composed, so leaving only the

structure of the piece open.

Those pieces from Brouwers second phase that do not have an open or

indeterminate form usually take on a linear, episodic structure, with little or no

repetition direct repetition. La Espiral Eterna (1972), which may be the archetypal

piece from this period, for instance, is presented in the form of four large episodes.

Each uses similar pitch material (and motives occasionally reappear, such as the rapid,

spiraling three-note cluster pattern in the opening and second sections). The sections

are completely different, however, in terms of texture, rhythm, tempo, and style, and

are heard one after another without transition. This is typical of the episode-form

pieces from the second period, and is also observed in Parabola (1973) and

Canticum, though in Canticum, the earliest of these works, material is more often

repeated.

Pitch Material

The chromatic colorations of extended tonal harmony that characterized Brouwers

early guitar music become the focus of the music of this middle period, as functional

harmony effectively disappears. Brouwers taste for seconds and sevenths is thrust to

the forefront, and clusters, or sonorities made out of semitones, become central

devices in his harmonic language. He transforms chromatically designed melodies

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

11/20

into vertical harmonies (again, primarily made out of major seventh intervals), and

begins to use unpitched, percussive sounds generously. These sounds are an important

addition to his musical language of this period, as their use emphasizes how

Brouwers composition has moved away from functional tonality, and toward a

concern for the qualities of sound in and of itself.13

This likewise signals a move away

from the traditional- German even- hierarchical, integrated structure of music, toward

a compositional mode of thinking based on atmosphere, variety, and (in the case ofLa

Espiral Eterna, at least) fracture. Perhaps the conventional view that during this

period Brouwer moved more strongly from tradition toward innovation has merit after

all.

The usage of sevenths and seconds inLa Espiral Eterna, as well as Canticum

(from 1972 and 1968 respectively) demonstrates how Brouwer deals with pitch in this

period. After the opening ofCanticum, a brief, unmeasured melody closes with a

downward leap of a major seventh, before the first sustained sonority of the piece, an

open cluster of A, B flat, and B natural, approached from above via G sharp. This

sonority turns into a structural feature, as the first movement closes with a leap up a

minor ninth from F to F sharp, up another to G, then down nearly three octaves to the

guitars lowest A flat. Viewing this transposition and augmentation of the first open

cluster as a structural element is justified by the end of the piece, in which the A-B

flat-B cluster appears in its original form, is repeated, and is finally supplanted by a D

descending to a low E flat (achieved by a scordatura tuning of the sixth string E).

La Espiral Eterna stretches Brouwers use of clusters even further, as they

become the element linking its four episodes and ultimately lend a sense of coherence

13

As a simple guide, the extended techniques and percussion sounds that Brouwer added to

his language during this period include scratching the wound strings with the fingernails,

tambora (striking the strings with the hand),golpe (striking the sound board), simultaneousright-hand and left-hand hammered on pizzicato, left-hand surface pizzicato, in which the

left hand lightly damps the strings and moves toward an approximate pitch, and Bartok or

snap pizzicato playing.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

12/20

to the piece. The piece could be heard as four methods of expressing the same

growing and shrinking cluster of seconds. The opening episode (shown in ex. 7) is

based on a slowly changing but rapidly plucked cluster, beginning on D, D sharp, and

E. Brouwer adds pitches one at a time, incrementally, to the bottom of the cluster as

he gradually removes them from the top. By halfway through the section, we find that

the cluster has moved down to A sharp, B, C, and D flat, before it finally bottoms out

on a grouping of F sharp, G, A sharp, and B. From this point, Brouwer removes

pitches one at a time until we are left with a lone B natural. A very similar motion of

pitch governs the second section, however this time the cluster rises, and is heard in

irregular, pizzicato groupings. Again, as the movement progresses, Brouwer removes

notes one by one until the listener is left with two pitches (E and F) on the treble

strings, which then rise via a surface pizzicato to an indeterminate but very high pitch,

beyond the neck and even the sound-hole of the guitar (ex. 5)

Example 5

This leads to a completely unpitched episode, in which the sound of clusters is

reflected in the rapid, irregular rhythmic hammering of the string against the

fingerboard (ex. 6).

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

13/20

Example 6

In this case the use of these extended sounds demonstrates that Brouwer now uses

sound itself, rather than functional tonality, to govern his musical language. When the

pitched cluster finally reappears- thus beginning the final episode- we find that its

pitch content has been expanded via inversion. The F sharp, G, and G sharp group

(again a lift in pitch from the ending of the second episode) is now expressed in a

spread of major sevenths. Yet again, Brouwer expands these as the group grows to

stretch from E, rising through D, C, and C sharp, to a high G. As opposed to the

delicate sound world of the opening episode, the process of pitch removal is this time

felt as an explosion of sound. Brouwer removes pitches until the guitar finally ends up

on a Bartok pizzicato minor second between F# and E, marked sfffzas well as let it

vibrate until the sound ends. The pizzicato clusters of the second episode briefly

return (interrupted by the Bartok pizz. again), before the ethereal opening texture, this

time focused on a low cluster of C, C sharp, and D, closes the piece by fading away. 14

Because Brouwer uses nearly the same pitch ideas in all four episodes of this

piece, he makes the structural divisions instead with regards to the sound itself,

defined by the use of varying regular and extended techniques. This again blurs

Brouwers position in the diametric conception of twentieth century music history.

14

For a more in-depth analysis of the piece see Eduardo Fernandez, Cosmology in Sounds,

1988, http://www.seiscuerdas.com/fernandez/?Articles.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

14/20

While the similar, unified usage of pitch material in all four episodes seems to place

him on the side of tradition, the variety and contrast achieved through other means-

mainly in the realm of technique- points toward his status as that of an innovator.15

Rhythm

A key feature of Brouwers rhythmic practice in his middle period is his use of

approximate rhythms. These appear in the form of proportional and spatial notation

for durations, groupings of stemless noteheads marked with terms such as fast,

irregular, and expanding and contracting beams denoting drastic accerlerando and

ritardando. He also sometimes expresses durations in seconds. Meterless music is

often his norm in this period, although some of the Cuban dance rhythms used in his

early period do surface from time to time.

The opening ofCanticum, Brouwer utilizes time (in seconds), rather than

beats, to specify the durations of events. He gives a chord a harsh rasgueado

(strummed) attack, with a duration marked below it as six seconds. This is followed

by four seconds of silence, before another six-second attack, this time followed by a

three second pause. Eventually this pattern gives way to a large section marked tempo

libero, without any bar lines of regular meter. The Cuban dance rhythms of the earlier

period do make a veiled appearance however, as the cinquillo becomes embedded in

the otherwise seemingly pulseless texture of the first movement.

16

Brouwers use of a pulseless rhythm becomes even more pronounced in La

Espiral Eterna. In the opening episode the previously discussed cluster appears as a

group of stemless notes, marked as fast as possible, repeated for a duration indicated

by a zig-zagging line leading to the next grouping of pitches. A similar line follows

each successive cluster. The proportional lengths of these lines indicate the amount of

15

Latham, table 1B.16

Leo Brouwer, Canticum, (Mainz: Gitarren-Archiv Schott, 1972), 3.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

15/20

time for which each cluster is repeated (ex. 7), with the total duration marked simply

as two minutes at the end of the section.

Example 7

Brouwer divides the figures in the second episode by a series of fermatas and breath

marks of an unspecified length, while the third episode is simply marked irregular,

and consists of a series of accelerating and decelerating percussive groupings (ex. 6).

The climax of the piece in the fourth episode is similarly unmeasured, and also

features the unspecific breath marks and fermatas. But this episode opens with the

only specified tempo and clear rhythmic notation in the piece, which bears an

uncanny resemble to the aforementioned Cuban dance rhythms Brouwer employs

throughout his oeuvre (ex. 8, see ex. 3).

Example 8

Brouwers usage of these rhythms is another example of the nationalist tendencies

inherited from the Grupo that influenced his early musical thought. It also shows that

the switch from his early phase to his middle one was less drastic than previously

thought.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

16/20

Third Period New Simplicity, 1980 on

With the composition ofEl Decameron Negro in 1981, Brouwer announced that he

had entered a new phase of his composition, described in the liner notes of the second

volume in theBrouwer: Guitar Music series of recordings issued by Naxos Records

as his national Hyper-Romantic style.17

This new phase is a return to the tendencies

of his early phase, though certain elements developed during the avant-garde period,

such as the use of extended technique, freedom of form, and unmeasured rhythms

continue to appear. His music from this period begins to draw on the influences of

popular music and New York minimalism, and also occasionally takes on clear

programmatic schemes. The titles of the three movements ofEl Decameron Negro

provide an example of this: The Harp of the Warrior, The Flight of the Lovers

through the Valley of Echoes, and Ballad of the Love-sick Maiden. Ultimately, this

music of this late period is a blending of and expansion upon the musical ideas of

Brouwers first two phases.

Form

Brouwer chooses his forms in this phase sporadically, moving freely from a linear

series of episodes reminiscent of his middle period in some pieces (El Decameron

Negro, 1981,Paisaje Cuban con Campanas, 1987) to strict passacaglia form in others

(An Idea, 1999). But his music makes a general return to the traditional structures of

the early period. After a short introduction, Viaje a la Semilla (2000) takes on the

verse-chorus-verse-chorus, structure found in the majority of popular music

(although this is accomplished through texture, not pitch usage), while strict

traditional forms again appear in Variations on a Theme of Django Reinhardt(1984)

and Sonata (1990).

17

Steven Thachuk inLeo Brouwer, Guitar Music Vol. 2, Elena Papandreou, Naxos compact

disc 8.554553.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

17/20

Pitch Material

The majority of analytical studies published on Brouwers oeuvre tend to glaze over

his pitch usage in the late period. There is good reason for this, as the harmonic

language of this phase seemingly regresses to the tonal one of his first period, with

chromaticism again used solely for color or effect, rather than as a central feature.

Brouwer himself offers a sound explanation for this harmonic regression, and in doing

so illuminates his own conception of dichotomy in twentieth-century music:

I became saturated with the language of the so called old avant-

gardethe atomized, crisp, and tensional language of this kindsuffered, and still suffers today, a defect related to the essence of

compositional balance, a concept that is present in history: Movement,

tension, with its consequent rest, relaxation. This law of opposingforces day-night, man-woman, ying-yang, time to love-time to hate

exists within all circumstances of mankind.The avant-garde lackedthe relaxation of all tensions. There is no living entity that doesnt rest.

This is one of the things I discovered.In this way, I made a kind ofregression that moves toward the simplification of the compositional

materials. This is what I consider my last period [which]

encompasses the essential elements from popular music, from classical

music, and from the avant-garde itself. They help me to give contrast

to big tensions.18

Viaje a la Semilla demonstrates Brouwers fusion of these elements. As stated, the

piece is largely tonal, governed by a drawn out V-I progression in E, opening with a

third-inversion B dominant seventh chord. A series of rapid, chromatically-decorated

arpeggios (b. 5) leads to a subdominant A major 9 in bar 11, spaced in consonant

sounding fifths with a sixth on the bottom. A dominant pedal B is rapidly plucked-

alluding to the sound world of Steve Reich- through the majority of the piece (the

verse sections, b. 22 33 and 68 96, for instance). Characteristics from the avant-

garde period appear in his use of extended techniques, as tonal material is attacked

18

Leo Brouwer, interviewed by Rodolfo Betancourt,A Close Encounter with Leo Brouwer,

1997, http://www.musicweb-international.com/brouwer/rodolfo.htm

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

18/20

with a series of Bartok pizzicatos (b. 2), and chords are built completely out of

harmonics (b. 14 16).

Rhythm

One can also see this fusion of elements in the rhythmic aspects of the music of this

period. Cuban dance rhythms are as prevalent as they were in earlier phases (El

Decameron Negro, Mvt. 2, figure G), while the unmeasured, approximate rhythms of

the avant-garde period continue to make appearances (An Idea, b. 18 20). Brouwer

develops a penchant for extremely repetitive rhythmic material- such as the repeated

B in Viaje a la Semilla- though he considers this a combination of the influence of

minimalist music andthe African roots of Cuban music.19

Conclusion

While commentators (and even Brouwer himself) have generally divided the

composers output into three distinct compositional categories, it seems more

pertinent to instead consider the trajectory of his work as following a single, linear

continuum, as innovative elements were continually added to his nationalist language,

first as an effort to bring his music to an international standard (as the tenets of the

Grupo demanded), then simply as a means for increased expression. It could be

argued that these extended techniques signify an increased knowledge of his medium

(the guitar) throughout the course of his career. The consistently complex yet

completely playable fingerings of his early music (Estudios Sencillos are a veritable

treatise in technique) however, show that his intimate knowledge of the guitar as a

medium was present all along. Except for a laying bare of chromaticism and

experiments with form in the middle period, his extended tonal language and use of

chromaticism as a coloristic element, combined with the various usage of Cuban

19

Brouwer, Betancourt interview.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

19/20

dance rhythms and traditional forms, are characteristics that are all present through his

entire oeuvre. This blend of elements, from the purely traditional to the completely

avant-garde, places Brouwer in a unique central position in the twentieth century

music dichotomy: not because he avoids venturing too far in either direction, but

because he ventures in both. Perhaps we must take scale into account when

considering this composers work. While in the global history of post-tonal music his

output can be considered quite traditional, in Cuba, it represents the forefront of

innovation.

-

8/22/2019 Brouwer Paper

20/20

Bibliography

Brouwer, Leo.Elogio de la Danza. Mainz: Gitarren-Archiv Schott, 1972.

---. Canticum. Mainz: Gitarren-Archiv Schott, 1972.

---.La Espiral Eterna. Mainz: Gitarren-Archiv Schott, 1972.---.El Decameron Negro. Paris: Edition Musicales Transatlantiques, 1982.

---. Interviewed by Rodolfo Betancourt,A Close Encounter with Leo Brouwer, 1997,http://www.musicweb-international.com/brouwer/rodolfo.htm (accessed 25

August 2009).---. Viaje a la Semilla. London: Chester Music, 2000.

---.An Idea (Passacaglia for Eli). London: Chester Music, 2002.

---. Guitar Music Vol. 2. Elena Papandreou. Naxos compact disc 8.554553.

---. Guitar Works. Paris: Editions Max Eschig, 2006.

Century, Paul Reed. Leo Brouwer: A Portrait of the Artist in Socialist Cuba. Latin

American Music Review, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Autumn Winter, 1987).

---. The principles of pitch organization in Leo Brouwers atonal music for guitar.

PhD diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 1991.

Fernandez, Eduardo. Cosmology in Sounds (On Leo Brouwers La Espiral Eterna).

1988. http://www.seiscuerdas.com/fernandez/?Articles (accessed 3 September2009).

Kronenberg, Clive, Guitar Composer Leo Brouwer: The Concept of a Universal

Language. Tempo 62, no. 245 (2008): 30 46.

Latham, Edward D. Binary Oppositions in Arnold WhittallsExploring Twentieth-

Century Music: Tradition and Innovation and Their Implications for

Analysis,Music Theory Online 10 no. 3 (2004).

http://mto.societymusictheory.org/issues/mto.04.10.3/mto.04.10.3.latham_fra

mes.html (accessed 27 August 2009).

Ortiz, Fernando.La Africania de la Musica Folklorica de Cuba. Habana: Editora

Universitaria, 1965.

Rodrguez, Victoria Eli. "Brouwer, Leo." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/04092(accessed 13 June 2009).

Schneider, John. The Contemporary Guitar. The New Instrumentation, edited by

Bertram Turetzky and Barney Childs. Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1985.

Suzuki, Dean Paul. The Solo Guitar Works of Leo Brouwer. Masters Thesis,

University of Southern California, 1981.

Tran, Kim Nguyen. The Emergence of Leo Brouwers Compositional Periods: The

Guitar, Experimental Leanings, and New Simplicity. Senior Honors Thesis,

Dartmouth College, 2007.

Whittall, Arnold.Exploring Twentieth Century Music: Tradition and Innovation.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.