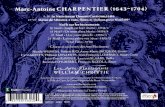

ŒUVRES POUR VIOLON : BARTÓK, MIYOSHI, JOLIVET

Transcript of ŒUVRES POUR VIOLON : BARTÓK, MIYOSHI, JOLIVET

AYA KONO, VIOLON

TAKUYA OTAKI, PIANO

HOMMAGE ÀANDRÉ JOLIVETŒUVRES POUR VIOLON : BARTÓK, MIYOSHI, JOLIVET

ŒUVRES POUR VIOLON : BARTÓK, MIYOSHI, JOLIVET

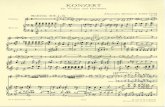

André Jolivet Suite rhapsodique pour violon seul

1. Praeludio — 4’31

2. Aria I — 3’59

3. Intermezzo — 4’06

4. Aria II — 2’07

5. Finale — 3’07

6. Béla Bartók Rhapsodie n° 1 pour violon & piano Lassù (Prima parte) Friss (Seconda parte) — 9’59

7. André Jolivet Incantation sur la corde de sol pour violon seul — 3’17

HOMMAGE À ANDRÉ JOLIVET

8. Akira Miyoshi Miroir pour violon seul — 9’02

André Jolivet Sonate pour violon & piano

9. I. Ramassé — 4’57

10. II. Librement (très lent) — 6’21

11. III. Bousculé — 7’10

AYA KONO – VIOLON

TAKUYA OTAKI – PIANO

durée totale — 58’54

4

Béla Bartók (1881 – 1945), André Jolivet (1905–1974) et Akira Miyoshi (1933–2011) : trois compositeurs du XXe siècle ayant écrit pour violon seul. À ce répertoire, la violoniste d’origine japonaise Aya Kono a choisi d’ajouter deux pièces avec piano qui partagent avec les précédentes des caractéristiques techniques, formelles ou esthétiques, notamment l’écriture rhapsodique ou la référence à un modèle classique. L’interprète s’interroge : « Comment atteindre la liberté après avoir maîtrisé les contraintes techniques ? »

Séduit par l’emploi de la section d’or pour structurer la forme, Jolivet revendique l’influence de Bartók, auquel il dédie sa Première sonate pour piano (1945), partageant avec lui le goût d’une énergie rythmique qui, de populaire, se fait primitiviste. Miyoshi, qui fit ses études à Paris avant de retourner au Japon, reste ancré dans une conception du temps très asiatique, tout en semblant refléter dans Miroir l’œuvre de Bach et celle de Ravel. En cela, sa musique s’approche de celle de Yin-Yang, ultime œuvre de Jolivet pour onze cordes solistes (1973), qui incarne le double intérêt du compositeur pour la pensée orientale et pour l’ascèse. Enfin, en filigrane, se dessine la figure du violoniste Devy Erlih, interprète privilégié de l’œuvre de Jolivet, ancien professeur d’Aya Kono, pour lequel ce répertoire n’avait pas de secret.

LIBERTÉ ET CONTRAINTES

5

Rhapsodie et incantation traduisent deux aspects de la liberté en musique. La rhapsodie, du grec rápto, qui signifie « coudre », offre une structure libre de tout modèle, « cousant » ensemble des fragments épars. Dédiée à Josef Szigeti, la Rhapsodie n° 1 de Bartók (1928) en possède les caractéristiques en même tant que celle du verbunkos, cette danse de recrutement de l’armée austro- hongroise faisant alter-ner lassù (Prima parte) et friss (Seconda parte). Bartók n’a pas révélé précisément ses sources, mais a indiqué au musico-logue Octavian Beu que la Rhapsodie n° 1 utilise des airs roumains et hongrois. À la structure ternaire d’une première partie

fondée sur des rythmes et une échelle tziganes succède une véritable rhapsodie, dont le thème principal a l’allure et les accents d’une danse populaire. Les idées se succèdent dans des caractères et des tempi contrastés (pesante, allegro molto) jusqu’au retour de l’élément initial, qui se transforme en une cadence conclue par un geste brillant.

Chez Jolivet, l’esprit rhapsodique se décline différemment. Le violoniste est bien un rhapsode, chantre d’une musique tantôt vocale, inspirée de traditions orientales, tantôt plus instrumentale et abstraite. Le compositeur en a fourni la

LIBERTÉ…

« Une œuvre pour instrument seul est une ascèse. Pour celui qui l’écrit : qui se doit de pénétrer la nature profonde de l’instrument, et dégager ses possibilités expressives les plus caractéristiques et d’en maîtriser la technique, afin de mettre en évidence l’ensemble de ses qualités. Pour l’interprète : qui doit, par son jeu et sa musicalité, magnifier les vertus de son instrument et, seul avec lui et partant de lui, donner l’impression qu’il recrée la musique de la façon la plus complète, la plus intense – et la plus naturelle 1. »

André Jolivet

6

clé : « En Israël (en 1963), au cours d’un congrès musical, j’ai pu entendre beau-coup de musiques hébraïques, des instru-mentistes et chanteurs du Moyen-Orient, et consulter de nombreux ouvrages sur la technique des instruments à cordes de ces régions. Véritable retour aux sources dont il m’apparut que notre occidental violon pouvait profiter aussi. Les sources d’inspiration de cette suite justifient qu’elle soit monodique. » Ici, le compositeur emprunte à Bartók le principe de la forme en arche. Construite en cinq mouvements, la Suite rhapsodique s’organise autour de l’« Intermezzo » qui en est le centre de symé-trie : de son murmure de doubles croches émerge un chant, noté « en dehors ». De part et d’autre, l’« Aria 2 » répond à l’ « Aria 1 », le « Finale » faisant pendant au « Praeludio ». Indiqué Vivo e marcato assai, ce final rappelle aussi Bartók par son énergie rythmique et l’utilisation d’ac-cords en pizzicato faits de superpositions de quintes. Le « Praeludium », dont le titre peut faire penser aux œuvres pour violon seul de Bach, ressortit au principe de l’incantation, dont on a fait l’emblème de Jolivet. Les Cinq incantations pour flûte seule de 1936, avec leur esthétique primi-tiviste combinée à une certaine moder-nité du langage, y ont contribué, tout comme l’Incantation … Pour que l’image devienne symbole (1937), conçue pour violon ou ondes Martenot : étrange alter-native instrumentale, qui en dit long sur

la sonorité éthérée, immatérielle, voulue par l’auteur, le titre indiquant lui-même un mouvement du concret vers l’abstrait, de l’art photographique de son dédicataire, Boris Lipnitzki, à l’idée. Aya Kono parle ici d’un « son comparable à celui de la voix humaine, d’un rêve d’abolir la matérialité de l’instrument ».

Trente ans plus tard, dans la Suite rhapsodique notamment, la force incanta-toire de la musique de Jolivet demeure : mélodies à la croissance germinale enrou-lées autour de notes pôles, répétition hyp-notique d’un même motif. Dans un mouve-ment très lent, la mélodie de l’ « Aria 1 » est du même type mais traitée cette fois par transposition, tandis que l’« Aria 2 » joue sur le glissando.

Miroir de Miyoshi, pièce que, selon le témoignage du compositeur, Devy Erlih faisait travailler à ses élèves du Conservatoire de Paris, utilise également des notes pôles, notamment le la grave, d’où naît le motif harmonique générateur de la pièce (une quinte juste et un demi ton), et sur lequel la pièce s’achève. Un motif mélodique non mesuré complète ce matériau désormais développé hori-zontalement, dont la fluidité est laissée à l’appréciation de l’interprète. Si des figures semblent se refléter, ce serait « plutôt dans un miroir déformant, voire brisé » (Aya Kono).

7

Cette grande liberté mélodique de la musique de Jolivet n’existe que dans un réseau de contraintes multiples, dans les domaines de la forme, du langage et de la technique instrumentale. Pièce de jeunesse éditée à titre posthume par Devy Erlih – qui avait entretemps épousé la fille de Jolivet, Christine – la Sonate pour piano et violon (1932) précède de quelques années le chef-d’œuvre de Jolivet pour piano, Mana (1935), et de deux ans à peine le Quatuor à cordes (1934), considéré par le compositeur comme son « testament scolaire ». Celui-ci propose une synthèse entre les deux ensei-gnements qui, bien qu’aux antipodes l’un de l’autre, ont marqué Jolivet : celui de Paul Le Flem et celui d’Edgard Varèse. Dès cette époque, Jolivet revendique son non-conformisme : « je n’en demande pas plus à ces premiers travaux. Il s’agit que l’on ait appris par eux ma position esthé-tique. Position que je conserverai coûte que coûte et qui me permettra peut-être dans l’avenir d’exprimer d’une façon non moins indépendante, mais, j’espère, plus parfaite, les nouveaux rapports sonores dont je sais l’existence et dont je pressens l’éclosion dans une expression artistique que je m’ef-force de découvrir et de fixer 2. »

S’inscrivant délibérément dans un genre classique, la Sonate pour piano et

violon illustre cette position. Le premier mouvement, à l’énergie bartokienne, est une forme sonate à deux thèmes contras-tés, dont la réexposition superpose les deux thèmes. Au centre, le mouvement lent s’appuie sur le total chromatique sans pour autant être sériel. Au-delà des retours du thème principal, qui pourraient être assi-milés au refrain d’un rondo, le final s’aven-ture dans un traitement des hauteurs qui préfigure Mana. Cette sonate, strictement contemporaine du Thème et variations de Messiaen pour violon et piano, a été créée par André Huot et Olivier Messiaen à la Société nationale en février 1935.

Au modèle formel s’ajoute les contraintes techniques. Ainsi, dans l’« Intermezzo » de la Suite rhapsodique, Jolivet demande une scordatura, la corde de la devant être accordée un quart de ton plus haut. On note également dans cette œuvre l’emploi de modes de jeu spécifiques, comme ce vibrato trillé dou-blé d’un glissando, très présent dans les mouvements extrêmes. Selon Aya Kono, l’obligation de jouer l’Incantation… Pour que l’image devienne symbole sur la corde de sol, implique quant à elle, « un son très profond, tandis que la limitation quasi spatiale produit une sensation d’étouffe-ment, rappelant Syrinx de Debussy, avec

… ET CONTRAINTES

8

une dimension plus sauvage ». Cette recherche sonore marque si profondément la poétique d’André Jolivet qu’il a choisi d’inscrire en exergue de son Concerto pour violon (1972) cette phrase de la cosmogonie hopi :

« L’essence de l’homme est sonore, le son engendre la lumière et l’esprit s’y manifeste. »

Lucie Kayas

1. André Jolivet, notice pour Cinq Églogues pour alto seul, André Jolivet, Écrits t. 2, p. 532, Sampzon, Delatour, 2006.

2. Archives André Jolivet, cité par Lucie Kayas in André Jolivet, Portraits, Arles, Actes Sud, 1994, p. 80.

9

Béla Bartók (1881 – 1945), André Jolivet (1905–1974) and Akira Miyoshi (1933–2011): three 20th century composers who wrote for solo violin. The Japanese-born violinist Aya Kono has chosen to add to this repertoire two pieces with piano which display similarities of technique, form and aesthetics, particularly in their rhapsodic writing or their references to classical models. The question for the performer is: “How to achieve freedom again after mastering the music’s technical constraints?”

An admirer of the use of the Golden Section in musical form, Jolivet cites the influence of Bartók, to whom he dedicated his First Piano Sonata (1945), and with whom he shared a taste for the sort of rhythmic energy which forges folk music into Primitivism. Miyoshi, who studied in Paris before returning to Japan, remains anchored in a very Oriental conception of time, whilst seeming to reflect in Mirror the works of Bach and Ravel. In this his music is similar to Yin-Yang, Jolivet’s last work for 11 solo strings (1973) and the embodiment of the composer’s interest both in Oriental thinking and in asceticism. And we can discern, like a watermark, the figure of Aya Kono’s teacher, the violinist Devy Erlih, renowned for performances of Jolivet’s music, for whom this repertoire held no secrets.

FREEDOM AND CONSTRAINTS

10

Rhapsody and incantation reflect two aspects of freedom in music. The Rhapsody, from the Greek rápto, which means “to sew”, is a completely free structure with no model, in which scattered fragments are “sewn” together. Dedicated to Josef Szigeti, Bartók’s Rhapsody N° 1 (1928) has characteristics of this style as well as that of the ver-bunkos, the Austro-Hungarian Army’s recruitment dance which alternates lassù (Prima parte) with friss ( Seconda parte). Bartók didn’t reveal his exact sources, but he indicated to the musicologist Octavian Beu that the Rhapsody N° 1 exploits both Romanian and Hungarian folksongs. After

a ternary first section with the rhythms and scale of gipsy music, we hear the veritable rhapsody, the tempo and accents of whose principal melody sound like a folk dance. Different ideas follow in contrasting styles and tempi (pesante, allegro molto) until the return of the main melody, which builds up to a virtuoso final cadence.

In Jolivet’s work, the rhapsodic spirit takes a different form. The violinist is a veritable rhapsode, a bard whose music is sometimes vocal, inspired by Oriental traditions, sometimes instrumental and abstract. The composer himself explained this: “In Israel (in 1963), during a music

FREEDOM...

Writing for a solo instrument is a form of asceticism: both for the composer, who must understand the deepest nature of the instrument, find its most characteristic expressive potential and understand its technique in order to show off all its qualities; and for the performer, alone with the instrument which is her starting point, whose playing and musicality must be harnessed to exploit the potential of her instrument to the full, giving the impression that she is recreating this music as fully, as intensely, and as naturally as possible.and take it further than anyone had before 1. ”

André Jolivet

11

congress, I heard a lot of Hebrew music, Middle Eastern singers and instrumental-ists, and read a good deal about the tech-nique of the region’s stringed instruments. It seemed to me that our Western violin would also profit from a proper return to its roots. These sources of inspiration are why this suite is written in monody.” Here, the composer has borrowed the idea of an arch-shaped form from Bartók. The five movements of the Suite Rhapsodique are organized around the “Intermezzo” which forms its centre of symmetry: from a murmur of semiquavers emerges a tune marked “en dehors”. On either side, the “Aria 2” is a reply to the “Aria 1”, and the “Finale” forms a pair with the “Praeludio”. Marked Vivo e marcato assai, this finale, with its rhythmic energy and use of piz-zicato chords of superimposed fifths, also reminds one of Bartók. The “Praeludium”, whose title evokes Bach’s works for solo violin, belongs to the essential principle of incantation so emblematic of Jolivet. The Five Incantations for solo Flute (1936), their Primitivist aesthetic combined with a certain modernity of language, con-tribute to this, as does the Incantation… To turn the Image into a Symbol (1937), written for violin or ondes Martenot – a strange instrumental choice which says a good deal about the ethereal, intangi-ble sound the composer wanted; even the title indicates a progression from concrete to abstract, from the photographic art of

its dedicatee, Boris Lipnitzki, to pure idea. Aya Kono speaks here of a “sound like the human voice, a dream of abolishing the instrument’s materiality”.

Thirty years later, particularly in his Suite rhapsodique, Jolivet’s music is still rich in incantation: melodies which grow organically from polar notes, with hypnotic repetition of the same motif. The extremely slow tempo of the melody in “Aria 1” is sim-ilar, but employs transposition, whereas the “Aria 2” uses glissando.

Miyoshi’s Mirror, a piece which accord-ing to the composer Devy Erlih made his pupils study at the Paris Conservatoire, also uses polar notes, in particular low A, from which emerges the generic har-monic motif of the piece (a perfect fifth and a semi-tone), and to which the piece returns at the end. An unmeasured melodic motif completes this material which is now developed horizontally, its fluidity left up to the performer’s discretion. Although these motifs seem to reflect one another, they are “broken up, as if in a distorting mirror” (Aya Kono).

12

The great freedom of Jolivet’s music exists only within a complex network of constraints – of form, language and instrumental technique. The Sonata for piano and violin (1932) – an early work published posthumously by Devy Erlih, who had in the meanwhile married Jolivet’s daughter Christine – was followed a few years later by Jolivet’s piano masterpiece Mana (1935), and the composer considered his String Quartet, written two years after the Sonata, in 1934, as his “pedagogical legacy”. It offers us a synthesis of the two utterly contrasted teaching styles which had influenced Jolivet: those of Paul Le Flem and Edgard Varèse. Already back then Jolivet was resolutely non-conformist: “That is all I ask of these early studies. It was through them that I defined my own aesthetic position. A position I maintain come what may, and which may enable me in the future – with no less independence, but I hope with better results – to express the new sound connexions which I know exist and for which I am seeking to discover, develop and define a new form of artistic expression 2 ”.

The Sonata for piano and violin, a resolutely classical form, is an example of this position. The first movement,

its energy reminiscent of Bartók, is in sonata form with two contrasted themes, superposed in the recapitulation. The slow movement at the centre uses the whole chromatic scale without being serial. Beyond the repetitions of the main theme, which liken it to a rondo, the Finale is a voyage of discovery into the use of the high register which prefigures Mana. This sonata, an exact contemporary of Messiaen’s Theme and variations for violin and piano, was premièred by André Huot and Olivier Messiaen at the Société nationale in February 1935.

To the constraints of form are added those of technique. In the Suite rhapsodique’s “Intermezzo”, Jolivet asks for scordatura, with the A-string tuned a quarter-tone higher. He has some specific instructions, too, like the trilled vibrato combined with a glissando of which he makes extensive use in the first and last movements. According to Aya Kono, the instruction to play the Incantation… To turn the Image into a Symbol on the G-string implies “a very deep sound, whilst the almost spatial limitation gives a stifling effect, like Debussy’s Syrinx, but wilder”. This exploration of sound was such an essential element of Jolivet’s poetic expression that he chose the

… AND CONSTRAINTS

13

following sentence from Hopi Cosmogony as the epigraph to the Violin Concerto (1972):

“The essence of man is sound, sound engenders light and the spirit manifests itself.”

Lucie KayasTranslation : Sophie Ilbert Decaudaveine

1. André Jolivet, notes to Cinq Églogues for solo viola, in: André Jolivet, Écrits, tome 2, p. 532, Sampzon, Delatour, 2006.

2. André Jolivet archives, quoted by Lucie Kayas in André Jolivet, Portraits, Arles, Actes Sud, 1994, p. 80.

14

ベラ・バルトーク (1881–1945) アンドレ・ジョリヴェ (1905–1974) 三善晃(1933–2011),この3人の20世紀の作曲家は、いずれもヴァイオリン独奏曲を書いている。日本人ヴァイオリニストの河野彩は、CD制作にあたり、このレパートリーに、形式的、美学的に共通するものがある2曲のピアノデュオ作品を加えた。演奏家として、彼女は自問する。 « 技術的制約を乗り越えたのち、どのようにして自由へと到達できるのだろうか? »

ジョリヴェは、バルトークの影響を自ら認め、1945年に作曲した「ピアノソナタ第 1番」では黄金分割を用い、バルトークに曲を献呈している。形式に限らず、そもそもジョリヴェの原始主義は、バルトークの民衆音楽的なリズムの力強さを思い起こさせる。

パリで学んだ三善晃は、ラヴェルの音楽語法に大変造詣が深い。ヴァイオリン独奏曲「鏡」では、バッハの影響を見い出すこともできるが、しかし時間の概念という点においては大変東洋的である。彼の音楽は、東洋的な思想と禁欲的という点で、ジョリヴェ最晩年の作品「11の弦楽器のためのイン・ヤン」に通じるものもある。そして、河野彩がこれらの曲を選んだ背景には、ジョリヴェの専門家であり、河野自身が教えを受けたこともあるヴァイオリニスト、デヴィ・エルリの存在がある。

自由と制約

15

狂詩曲(rhapsodie)と呪文(incantation)は、音楽における自由な局面を表現している。ラプソディーは「縫う」という意味のギリシャ語、ラプト(rapto)が語源である。よって、断片的な要素を「縫い合わせる」という、形式の自由さを持ち合わせている。 シゲティに献呈された、バルトークの「ラプソディー第1番」は、自由な形式で書かれているが、基本的構造は、ハンガリーの徴兵の踊り「ヴェルブンコシュ(緩急2つの楽想の交代)」からなっている。バルトークは、「ラプソディー第1番は、ルーマニアとハンガリーの農夫の歌を素材としている」と、音楽学者オクタヴィアン・ベウに語っている。ツィガーヌのリズムと音階を用いた、バルトークらしさに溢れる第一楽章は、まさに狂詩曲であり、主要テーマは、民族舞踊の性格が前面に強調されている。テンポの対比を生かしながら、特徴的な楽想が次々と現れ、最後は主要テーマの再現の後、ヴァイオリンの輝かしいカデンツァ風の一節で締めくくられる。

ジョリヴェにおけるラプソディーの精神は違う形をとる。ヴァイオリン奏者は、吟遊詩人のように、東洋の伝統を喚起させる歌唱的な音楽と、もっと抽象的で器楽的な音楽とを奏でる。作曲家はこう述べている。「1963年に国際音楽会議に出席のためイスラエルに赴いた。そこでは、沢山のヘブライ音楽を、中近東の歌手や器楽奏者の演奏で聴き、また、この地方の弦楽器奏法についての文献を読む機会があった。これらは、我々西洋のヴァイオリン奏法にも応用できるのではないかと思われた。この組曲は、単声音楽ということ自体にインスピレーションを得ている。」「狂詩組曲」で、ジョリヴェはバルトークも多用したアーチ型の形式(ABCBA)を用いている。よって、この5つの楽章は、旋律が16分音符の囁きの中から浮かび出てくるよう指示された「間奏曲」を中心に、対照的に構成されている。つまり、1楽章のプレリュードは5楽章のフィナーレに、2楽章のアリアは4楽章の第二アリアに呼応している。 « Vivo e

自由…

« 独奏曲には大変な苦労がつきものだ。作曲家は、まず、楽器の本質を深く理解し、最も特徴的な表現の可能性を探り、その楽器の持つ美点を出来る限り引き出さなければならない。一方演奏家は、その演奏と自らの音楽性で、楽器の長所を最大限に高め、最も完全で力強く、そして最も自然に音楽が生み出されているような印象を与えなければならない 1。 »

アンドレ・ジョリヴェ

16

marcato assai »(生き生きと速いテンポで、充分に音をはっきりと)と指示された終楽章では、エネルギッシュなリズムと、ピチカートで演奏される5度の重なりの和音が、バルトークを思い起こさせる。また、Praeludium(前奏曲)と名付けられた第1楽章は、そのタイトルがバッハを連想させるが、ここでは、ジョリヴェのシンボルとも言える呪術的な音楽が展開される。1936年作曲の「フルート独奏のための5つの呪文」における原始主義的美学と現代的な語法の融合を思い出す。さらに、1937年作曲のヴァイオリン独奏曲「呪文…イメージが象徴となるために」では、この不思議なタイトルそのものが、実体のあるものから抽象への移り変わりを示しているように、実体を欠く、空気のように純粋な音の響きが紡ぎ出される。河野彩は、「ヴァイオリンから奏でられた音が、楽器という実体を超えて、限りなく人間の声のように純化する理想郷のイメージ。」と表現している。これらの曲よりも30年後に書かれた「狂詩組曲」では、ジョリヴェ特有の « 呪術的な力のある音

楽 »の傾向が顕著である。旋律は、核になる音を中心に派生して行き、同じモチーフの繰り返しにより、一種の催眠術のような効果をもたらす。非常にテンポの遅い2楽章と4楽章では、旋律の移調や、グリッサンド奏法などが効果的に使われている。

三善晃の「鏡」にも、核になる音を中心に構成する、同じような手法が見られる。この曲は、デヴィ・エルリが、パリ音楽院で、学生に課題曲として与えた事があるそうだ。ヴァイオリン低音部のLAの音から、曲全体に作用する完全5度と半音からなるハーモニーが生み出され、この同じ低音のLAの音で曲が終わる。拍節感の無いメロディーのモチーフが、水平に展開されていくハーモニーに絡み、常に流動的な音の風景を描く。「鏡」というタイトルから、ラヴェルのピアノ曲を連想するが、三善にとっての「鏡」は、 « 何らかの痛みで歪められ、ひび割れた鏡に、自らの芸術と厳しく対峙する作曲者自身が投影されているようにも感じる » と、河野彩は語る。

ジョリヴェの音楽におけるメロディーの自由さは、形式、語法、器楽奏法など様々な制約の中でのみ見られるものである。1932年に作曲された「ヴァイオリンとピアノのためのソナタ」は、若い頃の作品だが、デヴィ・エルリにより、遺作として出版されている。(ジョリヴェの娘クリスティーヌは、デヴィ・エルリ

と結婚した。)2年後の1934年には「弦楽四重奏」を、そして1935年にはピアノ曲「マナ」を続けて作曲しているが、この「ヴァイオリンとピアノのためのソナタ」は、作曲者自身により、「学習的要素の強い作品」と見なされている。この曲の中で、ジョリヴェは、全く傾向の異なる2人の師の教えを総括している。

…そして、制約。

17

その2人とは、ポール・ル・フレムとエドガー・ヴァレーズである。ジョリヴェは、すでにこの時期に、因習に屈しない精神を明らかにしている。「私は、これらの初期の作品に多くは望まない。だが、彼らと学ぶことによって、何としても守っていかなければならない自分の美学の姿勢をはっきりと意識した。それは、これから私たちが見出すであろう新しい音響秩序を、より完全な方法で表現することを可能にしてくれるだろうし、それを発見し、芸術表現において定着させるよう努めていかなければならないのだ。 2」

「ヴァイオリンとピアノのためのソナタ」は、完全に古典的なスタイルながら、この美学の傾向を明らかにしている。バルトーク風のエネルギーに満ちた第1楽章は、対照的な2つのテーマを持つ古典的なソナタ形式で書かれているが、再現部では、この2つのテーマが同時に組み合わされる。緩徐楽章では、半音階が多用されているが、セリー(音列)を使って書かれているわけではない。最終楽章は、ロンド形式のルフラン(繰り返される主題)のようにも聴こえる主要テーマの何度かの再現が見うけられるが、最低音域、最高音域での様々な試みは、ピアノ曲の傑作

「マナ」を予感させる。このソナタは、メシア

ンの「ヴァイオリンとピアノのための、テーマとヴァリエーション」と全く同時代の作品であり、1935年2月に、国立音楽協会の演奏会で、アンドレ・ユオのヴァイオリン、メシアンのピアノにより初演されている。幾つかの技術上の制約の例を挙げると、「狂詩組曲」では、トリルをしながらグリッサンドというような特殊奏法が使われ、3曲目の「間奏曲」では、A線を¼音高く調弦するよう指示されている。また、「呪文…イメージが象徴となるために」では、全曲を通してG線で弾くことを強いられ、そのために、「深い響きが得られるが、この空間的制限は一種の息苦しさを生む。ドビュッシーの「シランクス」を思い起こすが、それよりは、もっと野生的な感覚である。」と、演奏者、河野彩は告白している。このような響きの探求は、ジョリヴェの詩的精神を深く啓発した。1972年作曲のヴァイオリンコンチェルトの冒頭に、ジョリヴェ自身が引用した、ホピ族の宇宙進化論の一節をここに記しておこう。

« 人類の本質は響きである。音が光を生み、そして、そこに魂(エスプリ)が宿る。 »

ルーシー・カヤス日本語訳 渡辺りか子

1. アンドレ・ジョリヴェ「ヴィオラソロのための5つの田園詩」解説より引用。出典:アンドレ・ジョリヴェ「書簡」vol.2 p.532 サンソン、ドラトゥール出版 2006年

2. 「アンドレ・ジョリヴェの肖像」p.80(アルル、アクト シュッド出版 1994年 )の中で、ルーシー・カヤスにより引用。

18

AYA KONO

(FR) Née à Kyoto, diplômée de l’univer-sité de Toho Gakuen au Japon, Aya Kono se forme auprès d’Aguri Suzuki, Akiko Tatsumi, et Yoshio Unno. Elle participe à plusieurs éditions du festival Argerich à Beppu au Japon, où elle a le privilège de jouer aux côtés de Yuri Bashmet, Gidon Kremer, Mario Brunello et Martha Argerich, en tant que premier violon de l’ Orchestre Toho.

Venue se perfectionner à Paris, elle reçoit l’enseignement de Devy Erlih à l’École normale de musique, et de Patrice Fon-tanarosa à la Schola cantorum, avant d’être admise au Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris. Après un Master de violon dans la classe d’Olivier Charlier et Joanna Matko-wska, elle y poursuit ses études en master de musique de chambre avec François Salque, ainsi qu’en 3e cycle dans la classe d’Hae-Sun Kang, recevant le Diplôme d’ar-tiste interprète – Répertoire contemporain et création. Elle a remporté les premiers prix des concours de Brest, Léopold Bellan et Luigi Zanuccoli.

Chambriste aguerrie, elle participe à de nombreux projets couvrant des réper-toires variés, de la musique baroque à la

musique du XXIe siècle. Sa passion pour la réflexion musicale la conduit à recevoir les conseils de musiciens comme le pianiste et pianofortiste Patrick Cohen ou le composi-teur Masahiro Ishijima.

Elle est invitée à se produire sur des scènes prestigieuses comme le Lucerne Academy Festival, le Printemps des arts de Monte-Carlo, le Konzerthaus de Vienne, Radio France, la Philharmonie de Paris et la Cité de la Musique, où elle a interprété Corale de Luciano Berio avec l’Orchestre des Lauréats du Conservatoire de Paris.

Violoniste à l’Ensemble Regards, elle col-labore avec l’Ensemble Intercontempo-rain, l’Ensemble Court-Circuit, l’Ensemble MusikFabrik, et enseigne au Conservatoire de Chantilly.

19

(EN) Aya Kono was born in Kyoto and graduated from the Toho Gakuen School of Music in Japan. She studied with Aguri Suzuki, Akiko Tatsumi and Yoshio Unno. She took part several times in Argerich’s Meeting Point in Beppu, Japan, where as 1st violin with the Toho Orchestra she had the privilege of playing alongside Yuri Bashmet, Gidon Kremer, Mario Brunello and Martha Argerich.

She moved to Paris to continue her stu-dies, working with Devy Erlih at the École Normale de Musique de Paris, and with Patrice Fontanarosa at the Schola Canto-rum before joining the Paris Conservatoire (Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris). After a Master’s degree in Olivier Charlier and Joanna Matkowska’s violin class, she stayed on to complete a Master’s in chamber music with François Salque, and a doctoral level performance diploma with Hae-Sun Kang in contemporary repertoire and premiere performance. She won first prize in the Brest, Léopold Bellan and Luigi Zanuccoli competitions.

A seasoned chamber musician, she has taken part in many projects across a wide variety of repertoires from Baroque

to contemporary music. Her passion for musical reflection has led her to seek the advice of musicians such as the pia-nist and pianoforte player Patrick Cohen or the composer Masahiro Ishijima. She is invited to perform in such prestigious venues as the Lucerne Academy Fes-tival, the Printemps des Arts in Monte-Carlo, the Vienna Konzerthaus, Radio France, the Philharmonie de Paris and the Cité de la Musique, where she perfor-med Lucian Berio’s Corale with the Paris Conservatoire’s Orchestre des Lauréats.

She is the Ensemble Regards’ violinist, and she also works with the Ensemble Inter-contemporain, the Court-Circuit Ensemble, and the Ensemble MusikFabrik. She teaches at the Chantilly Conservatoire.

20

(JP) 河野彩京都市生まれ桐朋女子高等学校音楽科を経て、桐朋学園大学音楽学部を卒業。辰巳明子、 海野義雄、鈴木亜久里の各氏に師事。別府アルゲリッチ音楽祭に度々参加。桐朋学園オーケストラのコンサートミストレスとしてY.バシュメット、G.クレーメル、M.ブルネロ、M.アルゲリッチらと共演。

2010年渡仏。スコラカントルム音楽院にてP.フォンタナローザ氏に、エコールノルマル音楽院にて故D.エルリー氏に師事。2015年パリ国立高等音楽院修士課程卒業。O.シャルリエ、J.マトコウスカの各氏に師事。同音楽院第三課程現代音楽科、及び室内楽科修士課程を修了。CRRパリ地方音楽院にて室内楽をE.ストロッセール氏に師事。パリ国立高等音楽院桂冠オーケストラとルチアーノ.ベリオ作曲「コラーレ」競演。ブレスト国際コンコール室内楽部門、レオポルド.ベラン国際コンクール室内楽部門、ルイージ.ザヌッコリ国際コンクール室内楽部門にて1位受賞。

これまでにルツェルン現代音楽アカデミー、ウィーンコンツェルトハウスを始め、エジンバラ、モナコ、ベルリン、スペイン、フランス各地の音楽祭に招待されソロ、室内楽、アンサンブルで演奏を行う。フランス内外の演奏家と室内楽で多数共演。

Ensemble Intercontemporain、Ensemble CourtCircuit、Ensemble MusikFabrik などフランス内外の現代アンサンブルに招待され演奏を行なう。Ensemble Regardメンバー。

古典から現代音楽まで様々なプロジェクトに取り組み、多くの作曲家と交流、初演、演奏に携わる。日本でも、テッセラの秋第19回音楽祭「新しい耳」に出演など、意欲的に活動する。シャンティー音楽院にて講師を務める。

21

TAKUYA OTAKI

(FR) Né au Japon, Takuya Otaki a étudié à l’Université de Musique et des Beaux-Arts d’Aichi, dans les classes de Yuzo Kakeya et Vadim Sakharov, et y a obtenu plu-sieurs récompenses : Kuwabara Prize, Best Student Prize et bourse de la Fondation Niwa. Après cette formation classique, il entre en 2013 en Master spécialisé en musique contemporaine à la Stuttgart Musikhochschule, dans la classe de Thomas Hell. Il est admis en 2016 à l’Internationale Ensemble Modern Akademie de Francfort, puis en septembre 2017, en Diplôme d’ar-tiste interprète – Répertoire contemporain et création au Conservatoire national supé-rieur de musique et de danse de Paris.

En février 2016, il remporte le Premier Prix du 12e Concours international de Piano d’Orléans, et se produit la même année en tournée en Italie, au Japon et en France. En 2017, invité de festivals à Lille et Mantoue, il prend part aux tournées de l’International Ensemble Modern Akademie de Francfort en Allemagne, Finlande et Hollande, et enregistre son premier disque, Béla Bartók et la virtuosité, paru chez Fy-Solstice. En 2018, il interprète le troisième concerto de Bartók avec l’Orchestre symphonique d’Or-léans, le premier concerto de Tchaïkovski et le deuxième de Chostakovitch à Niigata, et se produit en récital à Tokyo, Nagaoka

et Nagoya, ainsi qu’en Corée du Sud, où il donne également des masterclasses à l’Université nationale de Séoul.

(EN) Born in Japan, Takuyo Otaki stu-died at the Aichi Prefectural University of the Arts with Yuzo Kakeya and Vadim Sakharov, and won several prizes: the Kuwabara Prize, the Best Student Prize, and a bursary from the Niwa Founda-tion. After a classical training, he joined the Stuttgart Musikhochschule in 2013, studying with Thomas Hell and obtaining a Master’s degree in piano, specialising in contemporary music. He joined the Master’s programme in contemporary music at the International Ensemble Modern Akademie in Frankfurt in 2016, and in September 2017 joined the Paris Conservatoire for the doctoral level per-formance diploma in contemporary reper-toire and premiere performance.

In February 2016 he won first prize at the 12th International Piano Competition of Orléans and performed on tour in Italy, Japan and France. In Spring 2017 he performed in Paris and at the Lille and Mantua Festivals. In 2017 he played for the Frankfurt International Ensemble Modern Akademie on its tours in Germany, Finland and Holland, and made his first

22

recording, Béla Bartók et la virtuosité, with Fy- Solstice. In 2018 he performed Bartók’s 3rd piano concerto with the Orléans Sym-phony Orchestra, Tchaikovsky’s 1st piano concerto and Shostakovich’s 2nd in Niigata, and gave recitals in Tokyo, Nagaoka and Nagoya as well as venues in South Korea, where he also gave masterclasses at Seoul National University.

(JP) 新潟県長岡市出身。長岡高校普通科卒業。愛知県立芸術大学及び大学院を首席で卒業。ドイツ国立シュトゥットガルト音楽演劇大学大学院修了。アンサンブルモデルン·アカデミー(フランクフルト)修了。現在パリ国立高等音楽院第三課程現代音楽科修了。

中部ショパン学生ピアノコンクール金賞、野島稔よこすかピアノコンクール第3位など、いくつかのコンクールで入賞後、2016年フランスで行われたオルレアン国際ピアノコンクールで優勝。及びモーリス·オハナ賞、オリヴィエ·グレフ賞受賞。

これまでにフランス、イタリア、ブルガリア、日本、韓国で多くのリサイタルや音楽祭に出演。アンサンブル奏者としてもドイツを中心にヨーロッパ各地でコンサートを行い、これまでにアンサンブル·モデルン(ドイツ)、アンサンブル·アンテルコンタンポラン(フランス)など、ヨーロッパの著名な現代音楽アンサンブルと共演している。

協奏曲のソリストとしても、オルレアンシンフォニーオーケストラ、パリ音楽院ロレアオーケストラ、新潟セントラルフィルハーモニー管弦楽団などと共演。また講師として日本のみでなく、フランス各地10箇所の音楽院でのマスタークラスや、ソウル大学音楽学部でのワークショップを行い好評を得る。

2017年にフランスでデビューCD“ベラ·バルトークとヴィルトゥオージティ”をリリースし、フランスの各紙で高評価を得る。

これまでに内宮弘子、斎藤竜夫、松川儒、掛谷勇三、ヴァディム·サハロフ、トーマス·ヘル、ウエリ·ヴィゲットの各氏に師事。

2019年夏に日本に完全帰国。

23

REMERCIEMENTS

Je souhaite remercier Christine Jolivet-Erlih, qui soutient et encourage chaleureusement ma vie musicale à Paris, et sans laquelle ce projet d’enregistrement n’aurait pu voir le jour. Je dédie ce disque à Christine, ainsi qu’à son défunt mari Devy Erlih, mon inoubliable professeur.

Photographies : Ferrante FerrantiConception graphique : Mioï LombardCommunication : Alexandre Pansard-Ricordeau

℗ Initiale 2018 © Initiale 2019 – INL 04Enregistrement réalisé en septembre 2018 par le service audiovisuel et édité par le service des éditions du Conservatoire de Paris, avec le soutien de Madame Christine Jolivet-Erlih.Prise de son et mixage : Jean GauthierDirection artistique et montage : Théo Terracol, élève en Formation supérieure aux métiers du son (FSMS).

本プロジェクトの発起人であり、パリに留学して以来の私の音楽人生を見守り続けてくれているクリスティーヌ ジョリヴェに心からの感謝の意を表すとともに、このディスクをクリスティーヌに、そして彼女の夫であり私の恩師であ る、亡きデヴィ エルリー先生に、捧げます。