Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

-

Upload

susana-ocegueda-perez -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

1/12

De la Riva S, Muoz-Navas M, Sola JJ. Gastric carcinogenesis.Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2003; 96: 265-276.

1. INTRODUCTION

Currently, gastric adenocarcinoma is still a serioushealthcare concern, and the second most frequent malig-nancy worldwide (1). Although overall incidence hasseemingly decreased, both its frequency and mortalityrate show relevant geographic variability. In Easterncountries, Eastern Europe, and South America the inci-dence of this disease reaches epidemic proportions, and isthe first cause of death from malignant growths (2). Incontrast, the incidence of this disease is low in other geo-graphic regions (North America, Western Europe, Aus-tralia, New Zealand and Israel). Such differences havebeen partly attributed to both environmental and nutri-tional factors in terms of food preservation and prepara-tion, and to infectious factors related to the incidence of

H. pylori infection in the population. The potential in-fluence of these factors is such that the increasingly de-creased incidence and mortality rate of this disease seenfrom the 1930s to the last 10 years has been attributed todietary and food preservation changes (3-5).

However, this change in environmental factors doesnot fully account for known geographic variations or thevarious progressions and prognoses this condition mayentail.

It is nowadays accepted that gastric carcinogenesis is a

progressive process in which multiple environmental andepidemiologic, as well as genetic factors play a role, andwhose interactions seem to influence not only the devel-opment but also the progression of the disease (6).

2. CARCINOGENIC FACTORS

2.1. Environmental factors

During the past few years, and given that gastric can-cer is still one of the most common malignancies world-

wide, many studies focused on the identification of envi-ronmental risk factors responsible for its wide geographicvariability.

Nutritional factors

Populations with a high consumption of salt, smokedfood, hot spicy dishes, or fried fat have a high incidenceof gastric adenocarcinoma, which suggests a potentialrole in carcinogenesis (5,7-10).

Nitrite-rich food or water, high carbohydrate ingestion,and scarce access to and consumption of fruits, fresh ve-

getables, milk, vitamins A, C and E, and selenium seemto augment the risk of gastric cancer (3,5).Factors classically considered carcinogenic such as to-

bacco, alcohol or green tea are the subject of still incon-sistent results in the literature (6,11).

A progressive increase of gastric cardial adenocarcino-mas in industrialized countries versus predominantly dis-tal varieties and virtually no proximal cases in devel-oping countries may be currently highlighted (9,10).Such differences are attributed to a higher incidence ofgastroesophageal reflux disease in developed countries inassociation with diet and increased obesity rates, and to achronic use of proton pump inhibitors; this results in sali-

Gastric carcinogenesis

S. de la Riva, M. Muoz-Navas and J. J. Sola1

Services of Digestive Diseases and1Pathology. Clnica Universitaria de Navarra. Pamplona. Navarra, Spain

1130-0108/2004/96/4/265-276REVISTA ESPAOLA DE ENFERMEDADES DIGESTIVASCopyright 2004 ARN EDICIONES, S. L.

REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid)Vol. 96. N. 4, pp. 265-276, 2004

Recibido: 03-10-03.Aceptado: 07-10-03.

Correspondencia: Susana de la Riva Onanda. Servicio de Aparato Digesti-vo. Clnica Universitaria de Navarra. Avda. Po XII, 36. 31008 Navarra.Telf.: 948 25 54 00. Fax: 948 29 65 00.

POINT OF VIEW

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

2/12

va nitrates becoming nitrites, which favor the condition(12).

H. pylori infection

In the early 1980s the presence of a bacterium thatwas initially called Campylobacter piloridis (13) andsubsequently C. pylori was unveiled in gastric mucosabiopsy samples from patients with gastritis. It is currentlydesignated Helicobacter pylori. These are spiral-shapedbacteria belonging in the gram-negative germs group thatuse a wide variety of strategies to survive in acid media.

Chronic H. pylori infection leads to chronic gastritisthrough the activation of a complex network of inflam-matory mediators including IL-8, pro-inflammatory cyto-kines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF) and immunosuppressive pepti-des (IL-10) (14).

This chronic inflammation in turn leads to cell cyclechanges, which favor epithelial cell replication and thusincrease both the apoptotic rate and the release of oxid-izing substances. All this in combination with a depletedantioxidant defense predisposes against gastric carcino-genesis by increasing the chances of DNA mutations(14).

Such cumulative mutations may lead to the develop-ment of premalignant lesions and start the process frommetaplasia through dysplasia to gastric adenocarcinoma(4,15).

Chronic H. pylori infection is currently considered aGroup I carcinogen by the World Health Organization

(WHO) (16), and seems to play a relevant role in the de-velopment of distal gastric adenocarcinoma.A number of clinical and epidemiological studies have

reported this association, and it is estimated that at least1% ofH. pylori infections may lead to the developmentof gastric cancer following the aforementioned sequence(17), with risk increasing by 2.7 to 12 times over that of

the general population (18). Overall, 8% of gastric tu-mors are etiologically related toH. pylori infection (19).

Similarly to the incidence of this disease, the popula-tion-based rate ofH. pylori infection exhibits a lot of geo-graphic variability. Overall, areas with a high risk of gas-

tric adenocarcinoma show high H. pylori infection rates(20,21).Similarly, a higher incidence of gastric cancer has been

reported in low socio-economic status populations. Thisobservation seems to be partly related to nutritional fac-tors such as restricted access to and consumption of freshfruits and vegetables, and/or higher, earlier-ageH. pyloriinfection rates (22).

In an attempt to explain the higher association ofconcomitantH. pylori infection with intestinal-type ver-sus diffuse-type adenocarcinoma, two distinct evolutionpaths have been proposed in relation to gastric cancer his-tology, with a number of progressive histologic changes

occurring in intestinal-type adenocarcinoma but not in dif-fuse-type adenocarcinoma (23) (Fig. 1).

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection

Discovered by Epstein in 1964, this is an icosahedralherpesvirus containing a double linear DNA strand. Itwas first put in relation to gastric cancer in 1990, fol-lowing the detection of its genetic material in patientswith gastric cancer by PCR and in situ hibridation (24).This association has been revealed by numerous studiesfrom various geographic regions (25,26).

In contrast withH. pylori, this viral infection has beendetected in both the diffuse and intestinal type of gastriccancer (27).

Its carcinogenic mechanism is still unknown. Two car-cinogenesis pathways have been suggested according tothe presence or absence of concomitant infection by thisvirus (28).

266 S. DE LA RIVA ET AL. REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid)

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2004; 96(4): 265-276

TUBULAR

CHRONIC GASTRITIS

H. PYLORI INFECTION

Atrophy Type III IM Dysplasia Early Ca. Advanced Ca.

Atypical hyperplastic glands Early Ca. Advanced Ca.

DIFFUSE

IM: intestinal metaplasia: Ca: carcinoma

Fig. 1.- Relationship of carcinogenesis to H. pyloriinfection (23).Relacin de carcinognesis con la infeccin porH. pylori (23).

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

3/12

2.2. Genetic factors

Regarding the influence of genetic factors on the devel-opment of gastric adenocarcinoma, this cancer has beendetected in families for two or three generations, and

members in a family with a history of gastric adenocarci-noma have a two- or even three-fold increased risk whencompared to the general population, which implies a po-tential for familial aggregation (29).

However, studies including members of only one fa-mily are limited and results are influenced by environ-mental factors, since members belonging to a same fa-mily usually share the same dietary and environmentalconditions (29).

An observation that indirectly points to a potential roleof genetic factors in gastric carcinogenesis is this condi-tions higher association with blood group A versus theremaining blood groups. This association involves predo-

minantly males and the diffuse rather than intestinal his-tologic type (5,9,29).

2.3. Precursor conditions

A number of histologic changes in the healthy gastricmucosa significantly increase the risk of gastric adeno-carcinoma.

Notable among these are:

Chronic atrophic gastritis

A premalignant lesion present in 90% of gastric ade-nocarcinomas. It usually takes a lot of time until gastriccancer develops. In most studies with a patient follow-upabove 10 years, the risk of gastric cancer was of 1 in 150patients per year, and it went further up to 10% after 15years of follow-up (30,31).

Its carcinogenic mechanism seems to rely on decrea-sed hydrochloric acid and pepsin secretion, and increasedgastric pH, which encourages a proliferation of dietarynitrate-reducing germs. Nitrosamide and nitrosamine for-mation, together with a number of dietary factors such as

excessive salt ingestion or inadequate consumption offresh vegetables and fruits, may induce DNA mutationsin epithelial cells, thus favoring the development and pro-gression of tissue changes such as intestinal metaplasiaand dysplasia, which are considered premalignant lesions(4,32).

Pernicious anemia

A condition that exhibits gastric atrophy and increasesthe risk of gastric cancer (33), even though only 5-10% ofsuch patients will eventually develop it (31).

Partial gastrectomy

Patients with benign conditions undergoing this surgeryhave an increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma as of 10years following the procedure (34). Risk increases by 50

and 70%, respectively, at 15 and 25 years after surgery (31).

Mntriers disease (hypertrophic gastric disease)

The risk of developing gastric cancer from this tissuechange is high, and is estimated as 10-15% in some series;however, as this condition is extremely rare in its own right,such transformation percentage is therefore negligible (35).

Adenomatous polyps

Polyps are a common finding at the gastric mucosa.They may be classified into two types:Non-neoplastic polyps with no potential for degene-

ration (hyperplastic, hamartomatous, inflammatory andheterotopic polyps).

Neoplastic polyps: adenomas. They amount for 15-20% of polyps found at the gastric mucosa. They are po-tentially neoplastic with an incidence of malignizationaround 5-15% of tubular adenomas and 15-75% of vil-lous adenomas. Their tendency towards becoming malig-nant is directly related to polyp size and the presence ofdysplasia and its grade (36).

Peptic ulcer

Chances that benign peptic ulcer may transform into amalignancy are still under discussion and opinions vary.Even though most authors refuse this possibility, the rolethat H. pylori infection seems to play in the process ofgastric carcinogenesis should be considered (37).

Barretts esophagus

The increased incidence of gastric cardial adenocarci-

noma in developed countries seems to be closely relatedto their increased incidence of gastro-esophageal refluxdisease and Barretts esophagus (38,39). Wider-scopestudies are still needed to determine other factors playinga role in its development, thus allowing to establish whe-ther proximal gastric cancer has a different pathogenesisversus distal gastric cancer.

2.4. Molecular factors

Although evidence that genetic changes play a signi-ficant role in the multistep process of gastric carcinoge-

Vol. 96. N. 4, 2004 GASTRIC CARCINOGENESIS 267

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2004; 96(4): 265-276

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

4/12

nesis and its progression is available, the huge numberof factors analyzed and the various results so far obtainedallow no definitive conclusions to be presently drawn(9, 40-42). What seems clear is that the conversion ofnormal gastric cells into tumor cells is a slow, gradual

process in which multiple molecular changes accumu-late, and this has been put on a level with the process ofcolorectal carcinogenesis. This accumulation of geneticchanges includes mutations and/or oncogene amplification-overexpression (c-Ki-ras, c-erb-B2, K-sam, hst/int-2, c-met,and c-myc), tumor suppressor gene inactivation (p53, APC,DCC, and RB1), and microsatellite alterations (loss of hete-rozygosity or microsatellite instability) in one or more chro-mosomal regions such as 1p, 5q, 7q, 12q, 13q, 17p, 18q,and even chromosome Y (40,43,44) (Table I).

Results from molecular studies on gastric cancer haverevealed the potential presence of two different carcinoge-nesis pathways depending on the adenocarcinomas histo-logic type diffuse or intestinal (45-49). Intestinal-typegastric cancer seems to be related to tissue changes such asintestinal metaplasia within the gastric mucosa, which so-

mewhat resemble the molecular progression of colorectalcancer (47). It follows a process that begins as chronic gas-tritis and then progresses through atrophic gastritis and in-testinal metaplasia to dysplasia (4). On the other hand, thenatural history of diffuse gastric cancer lacks such multis-tep evolution (46,50-52).

3. CURRENT CARCINOGENESIS MODEL

Laurens histological classification (1965) of gastriccancer into diffuse and intestinal types is most commonlyused by a majority of authors (53).

These two types of gastric cancer are probably a re-flection not only of morphological differences allowingtheir classification, but of their varying clinical, epide-miological and pathogenic characteristics.

Therefore, two distinct carcinogenesis pathways have

been suggested in relation to these histologic types ofgastric cancer, with differing influences of environmentalfactors and a varying presence and predominance of mo-lecular changes.

As previously stated, the intestinal type seems to developfrom a succession of tissue changes in a way that resemblesthe carcinogenetic pathway of colorectal cancer. Regardingenvironmental factors, OConnor et al (54), Watanabe et al(24), and Correa (4) suggested a spiral gastric carcinogenesismodel where an accumulation of environmental risk factorsentailed a shorter development period, while a reduction ofsaid factors resulted in prolonged development time (Fig. 2).

In addition, similarly to the above-mentioned authors,

Yasui et al. (42) collected all molecular factors analyzed andimplied in gastric carcinogenesis from the literature in an at-tempt to put it on a level with the colorectal carcinogeneticprocess. In view of differences reported between both histo-logic types of gastric adenocarcinoma, they suggested thattwo distinct development paths might exist, with differentmolecular changes being present or predominant (Fig. 3).

What does seem clear is that intestinal-type gastricadenocarcinoma carcinogenesis includes tissue changesthat may progress towards malignity and are consideredpreneoplastic in nature. Such lesions are intestinal meta-plasia and epithelial dysplasia.

In contrast, diffuse gastric adenocarcinoma does not

seem to evolve along this multistep process and appa-rently begins in a healthy gastric mucosa that is free ofprior tissue changes (34).

4. PREMALIGNANT LESIONS

Premalignant lesions are defined as those tissuechanges that may evolve to malignity and are involved ingastric carcinogenesis.

Intestinal metaplasia. Defined as the presence of diffe-rentiated epithelium similar to that of the small bowel. Itis classified according to both morphologic and histoche-

mical characteristics into:Complete intestinal metaplasia (type I).Incomplete intestinal metaplasia, either small intes-

tinal (type II) or colonic (type III).In type-I and type-II intestinal metaplasia goblet cells

produce syalomucins, whereas in type-III metaplasiathese same cells produce sulfomucins (55,56). Althoughthere seems to be an association between the presence ofintestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer. This premalig-nant lesion is of poor predictive value. Type-I intestinalmetaplasia is related to a low incidence of gastric cancer,whereas type-III metaplasia has a 2.7- to 5.8-fold greaterrisk of gastric cancer development (57,58).

268 S. DE LA RIVA ET AL. REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid)

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2004; 96(4): 265-276

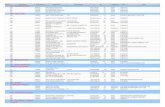

Table I. Major genes and chromosomes undergoing altera-tion during gastric carcinogenesis

Genes Chromosomal locus Genetic changes

OncogenesK-ras 12p12.1 Mutationc-erb-B2 17q21-q22 Amplificationhst-1 11q13.3 Amplificationint-2 11q13 Amplificationmet 7q31 AmplificationMyc 8q24 Amplification

Tumor suppressor genesp53 17p13.1 LOH*, MutationAPC 5q21 LOH*, MutationDCC 18q21 LOH*RB1 13q14.2 Mutation

E-cadherin 16q22.1 Mutation

Loss of heterozygosity 1p,5q,7q,12q, LOH*13q,17p,18q, Y

LOH: loss of heterozygosity.

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

5/12

Epithelial dysplasia. Characterized by the presence of

a number of histologic changes such as cell atypias withpleomorphism, increased non-differentiated cell num-bers, and abnormal crypt and gland layout.

Gastric epithelial dysplasia usually occurs in the settingof atrophic chronic gastritis, and is commonly associatedwith intestinal metaplasia. Dysplastic areas are commonlyfound around gastric adenocarcinomas, and are thereforeseemingly related both clinically and pa-thologically togastric cancer. While mild to moderate dysplasia tends toregress or remain stable in most cases, moderate and prima-rily severe dysplasia is commonly associated with gastricadenocarcinoma development (59) (Fig. 4).

Overall, in 10% of patients epithelial dysplasia may

progress towards gastric cancer in a term of 5 to 15 years,

but such dysplasia will regress or remain stable in mostpatients (60).

5. CONCLUSION

Gastric carcinogenesis is a slow and complex processin which multiple environmental and molecular factorsseem to play a role. Geographic differences in the inci-dence, outcome and prognosis of gastric adenocarcinomaseem to be partly related to the varying specific environ-mental (nutritional and infectious) factors to which popu-lations are exposed. In view of their more than likely in-

Vol. 96. N. 4, 2004 GASTRIC CARCINOGENESIS 269

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2004; 96(4): 265-276

Normal gastric mucosa

Chronic gastritis

Atrophic gastritis

Intestinal metaplasia

Dysplasia

Neoplasm

H. pylori infection

High salt ingestion

Preventive factors Risk factors

-carotenes

Fruits and

vegetables

H igh pH Bacter ia l g rowth

N=O mutagens

Food

Tobacco

Vitamin C

Spiral model

Fig. 2.- Carcinogenesis model for intestinal-type gastric cancer.Modelo de carcinognesis de cncer gstrico de tipo intestinal.

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

6/12

volvement, these factors have been thoroughly analyzedand have yielded conclusive results regarding the accessto and consumption of selected foods, as well as theirpreservation and preparation.H. pylori infection amongstthe population is another factor involved in the develop-ment of gastric cancer, and is nowadays considered aGroup I carcinogen by WHO.

Regarding molecular factors, their relevance is increa-

singly greater for gastric carcinogenesis, and they alsoplay a significant role in the development of this condi-tion. An accumulation of molecular changes seems to in-fluence gastric adenocarcinoma initiation and progres-sion, but its carcinogenic sequence has not beenestablished yet. What seems clear is that such sequencevaries according to the histologic type of gastric adeno-carcinoma. For this reason, the current categorization ofgastric adenocarcinomas by Lauren is considered to re-flect not only histologic but also epidemiologic, clinical,and prognostic differences, implying a possibility thattwo distinct, still unestablished carcinogenesis pathsexist.

REFERENCES

1. Roukos DH. Relevant prognostic factors in gastric Cancer. Ann Surg2000; 232: 719-20.

2. DeVita VT Jr. The war on cancer has a birthday, and a present. J ClinOncol 1997; 15: 867-9.

3. Forman D. Are nitrates a significant risk factor in human cancer?Cancer Surv 1989; 8: 443-58.

4. Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifacto-rial process-First American Cancer Society award lecture on cancer

epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res 1992; 52: 6735-40.5. Kramer BS, Johnson KA. Other gastrointestinal cancers: stomach, li-

ver. In: Greenwald P, Kramer BS, Weed DL, eds. Cancer preventionand control. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1995. p. 673-94.

6. Kabat G, Ng S, Wynder E. Tobacco, alcohol intake and diet in rela-tion to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. CancerCauses Control 1993; 4: 123.

7. Howson CP, Hiyama T, Wynder EL. The decline in gastric cancer:epidemiology of an unplanned triumph. Epidemiol Rev 1986; 8: 1-27.

8. Coleman M, Babb P, Damiecki P, Honjo S, Jons J, Knerer G. Cancersurvival trends in England and Wales, 1971-1995: deprivation andNHS Region. Studies in Medical and Population Subjets n 61. Natio-nal statistics, London, 1999.

9. Stadtlnder CT, Waterbor JW. Molecular epidemiology, pathogenesisand prevention of gastric Cancer. Carcinogenesis 1999; 20: 2195-208.

270 S. DE LA RIVA ET AL. REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid)

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2004; 96(4): 265-276

pS2 preservation

1p36 (p73) LOH

NORMAL

MUCOSA

POORLY

DIFFERENTIATED

EARLY

CARCINOMA

ADVANCED

CARCINOMA

INVASION/

METASTASIS

Genetic instability

Telomeric reduction

Telomerase activation

TERT expression

Aberrant CD44 transcripts

Cyclin E overexpression

CDC25B overexpression

P53

mutation/LOH Cadherin loss/mutationK-sam amplification

c - metamplification

E

Cr7q LOHCyclin amplification

P27 expression

Nm23 expression

GF overexpression

Aberrant CD44transcripts

D1S191 instability

DNA hypermethylation

APC mutation

P53 mutation

K-ras mutation c - erbB2 amplification

NORMAL

MUCOSA

pS2 reduction

INTESTINAL

METAPLASIA

ADENOMADIFFERENTIATED

EARLY

CARCINOMA

ADVANCED

CARCINOMA

INVASION/METASTASIS

P53 mutation /LOH

P27 expression

Modified by Yasui et al (42)

Fig. 3.- Molecular changes in gastric carcinogenesis.Alteraciones moleculares en la carcinognesis gstrica.

No

dysplasia

Mild

dysplasia

Moderate

dysplasia

Severe

dysplasiaGastric

cancer

5 years5 years

10%5 years

10%60% 60%

10%

3-24 months50-90%

Fig. 4.- Natural history of gastric dysplasia.Historia natural de la displasia gstrica.

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

7/12

10. Hemminki K, Jiang Y. Familial and second esophageal cancers: a na-tion-wide epidemiologic study from Sweden. Int J Cancer 2002; 98:106-9.

11. Kelley JR, Duggan JM. Gastric cancer epidemiology and risk factors.J Clin Epidemiol 2003; 56: 1-9.

12. Mowat C, Carswell A, Wirz A, McColl KE. Omeprazole and dietarynitrate independently affect levels of vitamin C and nitrite in gastric

juice. Gastroenterology. 1999; 116: 813-22.13. Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of

patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet 1984; 16: 1311-4.14. Bodger K, Crabtree JE. Helicobacter pylori and gastric inflammation.

Br Med Bull 1998; 54: 139-50.15. Forman D. Helicobacter pylori infection and Cancer. Br Med Bull

1998; 54: 71-8.16. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. Schistosomes, liver flukes

and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation ofCarcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon 1994; 61: 1-241.

17. Farthing MJ. Helicobacter pylori infection: an overview. Br Med Bull1998; 54: 1-6.

18. Cover TL, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori: a bacterial cause of gastri-tis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric Cancer. Am Soc Microbiol News1995; 61: 21-6.

19. Asghar RJ, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori and risk for gastric ade-

nocarcinoma. Semin Gastrointest Dis 2001; 12: 203-8.20. Reed PI, Hill MJ, Johnston BJ. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylo-ri. Lancet 1993; 16: 987-8.

21. Kikuchi S. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer.Gastric Cancer 2002; 5: 6-15.

22. Fontana V, Decensi A, Orengo MA, Parodi S, Torrisi R, Puntoni R.Socioeconomic status and survival of gastric cancer patients. Eur JCancer 1998; 34: 537-42.

23. Solcia E, Fiocca R, Luinetti O, Villani L, Padovan L, Calistri D, et al.Intestinal and diffuse gastric cancers arise in a different backgroundof Helicobacter pylori gastritis through different gene involvement.Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20 (Supl. 1): S8-22.

24. Watanabe S, Tsugane S, Yamaguchi N. Etiology. In: Sugimura T, Sa-sako M, eds. Gastric Cancer Oxford University Press, 1997. p. 33-51.

25. Tokunaga M, Land CE, Uemura Y, Tokudome T, Tanaka S, Sato E.Epstein-Barr virus in gastric carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1993; 143:1250-4.

26. Fukayama M, Hayashi Y, Iwasaki Y, Chong J, Ooba T, Takizawa T,et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma and Epstein-Barr virus infection of the stomach. Lab Invest 1994; 71: 73-81.

27. Shibata D, Weiss LM. Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric adeno-carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1992; 140: 769-74.

28. Ojima H, Fukuda T, Nakajima T, Nagamachi Y. Infrequent overex-pression of p53 protein in Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carci-nomas (abstract). Jpn J Cancer Res 1997; 88: 262-6.

29. Nomura A, Yamakawa H, Ishidate T, Kamiyama S, Masuda H, Stem-mermann GN, et al. Intestinal metaplasia in Japan: association withdiet. J Natl Cancer Inst 1982; 68: 401-5.

30. Kato I, Tominaga S, Ito Y, Kobayashi S, Yoshii Y, Matsuura A, et al.Atrophic gastritis and stomach cancer risk: cross-sectional analyses.Jpn J Cancer Res 1992; 83: 1041-6.

31. Gordon L. Tumors of the Stomach. En: Sleisenger, Fordtrans, eds.Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. Philadelphia: Saunders. 2002. p.

733-49.32. Correa P, Chen VW. Gastric cancer. Cancer Surv 1994; 19-20: 55-76.33. Hsing AW, Hansson LE, McLaughlin JK, et al. Pernicious anemia

and subsequent cancer: a population based cohort study. Cancer1993; 71: 745-50.

34. Werner M, Becker KF, Keller G, Hofler H. Gastric adenocarcinoma:pathomorphology and molecular pathology. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol2001; 127: 207-16.

35. Hsu CT, Ito M, Kawase Y, Sekine I, Ohmagari T, Hashimoto S. Earlygastric cancer arising from localized Menetrier's disease (abstract).Gastroenterol Jpn 1991; 26: 213-7.

36. Stolte M. Clinical consequences of the endoscopic diagnosis of gas-tric polyps. Endoscopy 1995 ; 27: 32-7.

37. Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Change Y, VogelmanJH, Orentreich N, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk ofgastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1991; 325: 1127-31.

38. Blot VJ, Devesa SS, Kneller RW. Rising incidence of adenocarcino-ma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA 1991: 265; 1287-9.

39. Clark GW, Smyrk TC, Buriles P. Is Barretts metaplasia the source ofadenocarcinomas of the cardia? Arch Surg 1994; 129: 609-14.

40. Tahara E. Molecular biology of gastric Cancer. World J Surg 1995;19: 484-90.

41. Fuchs CS, Mayer RJ. Gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:32-41.

42. Yasui W, Oue N, Kuniyasu H, Ito R, Tahara E, Yokozaki H. Molecu-lar diagnosis of gastric cancer: present and future. Gastric Cancer2001; 4: 113-21.

43. Ochia, A, Hirohashi S. Multiple genetic alterations in gastric CancerIn: Sugimura T, Sasako M, eds. Gastric Cancer Oxford UniversityPress. 1997. p. 87-99.

44. Wright PA, Williams GT. Molecular biology and gastric carcinoma.Gut 1993; 34: 145-7.

45. Tahara E. Molecular mechanism of stomach carcinogenesis. J CancerRes Clin Oncol 1993; 119: 265-72.

46. Correa P, Shiao Y H. Phenotypic and genotypic events in gastric car-cinogenesis. Cancer Res 1994; 54 (Supl. 7): 1941s-3s.47. Tahara E, Semba S, Tahara H. Molecular biological observations in

gastric Cancer. Semin Oncol 1996; 23: 307-35.48. Solcia E, Fiocca R, Luinetti O, Villani L, Padovan L, Calistri D, et al.

Intestinal and diffuse gastric cancers arise in a different backgroundof Helicobacter pylori gastritis through different gene involvement.Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20: S8-22.

49. Cho J-H, Noguchi M, Ochiai A, Hirohashi. Loss of heterozygosity ofmultiple tumor suppressor genes in human gastric cancers by polyme-rase chain reaction. Laboratory Investigation 1996; 74: 835-41.

50. Uchino S, Tsuda H, Noguchi M, Yokota J, Terada M, Saito T, et al.Frequent loss of heterozygosity at the DCC locus in gastric Cancer.Cancer Res 1992; 52: 3099-102.

51. Correa P. Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. Am J SurgPathol 1995; 19 (Supl. 1): S37-43.

52. Baffa R, Veronese ML, Santoro R, Mandes B, Palazzo JP, Rugge M,

et al. Loss of FHIT expression in gastric carcinoma. Cancer Res 1998;58: 4708-14.

53. Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma; dif-fuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. Acta Pathol MicrobiolScand 1965; 64: 31-49.

54. OConnor F, Buckley M, OMorain C. Helicobacter pylori: the can-cer link. J R Soc Med 1996; 88: 674-8.

55. Filipe MI. Natural history of precursor lesions to gastric carcinoma:growth factors and oncogenes in the metaplasia-dysplasia-carcinomasequence. Eur J Cancer Prev 1994; 3 (Supl. 2): 19-23.

56. Stemmermann G, Heffelfinger SC, Noffsinger A, Hui YZ, MillerMA, Fenoglio-Preiser CM. The molecular biology of esophageal andgastric cancer and their precursors: oncogenes, tumor suppressorgenes, and growth factors. Human Pathol 1994; 25: 968-81.

57. Rokkas T, Filipe MI, Sladen GE. Detection of an increased incidenceof early gastric cancer in patients with intestinal metaplasia type III

who are closely followed up. Gut 1991; 32: 1110-3.58. Werner M, Becker KF, Keller G, Hofler H. Gastric adenocarcinoma:pathomorphology and molecular pathology. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol2001; 127: 207-16.

59. Rugge M, Leandro G, Farinati F, Di Mario F, Sonego F, Cassaro M,et al. Gastric epithelial dysplasia. How clinicopathologic backgroundrelates to management. Cancer 1995; 76: 76-82.

60. Rugge M, Farinati F, Baffa R, Sonego F, Di Mario F, Leandro G, etal. Gastric epithelial dysplasia in the natural history of gastric cancer:a multicenter prospective follow-up study. Interdisciplinary Group onGastric Epithelial Dysplasia. Gastroenterology 1994; 107: 1288-96.

Vol. 96. N. 4, 2004 GASTRIC CARCINOGENESIS 271

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2004; 96(4): 265-276

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

8/12

272 S. DE LA RIVA ET AL. REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid)

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2004; 96(4): 265-276

1. INTRODUCCIN

El adenocarcinoma gstrico contina siendo en la ac-tualidad un importante problema sanitario a nivel mun-dial, ocupando el segundo lugar en frecuencia de los tu-mores malignos (1). Aunque de forma global suincidencia parece haber disminuido, tanto su frecuenciacomo su tasa de mortalidad muestran una importante va-riacin geogrfica. En los pases orientales, este de Euro-pa y sur de Amrica la incidencia de esta enfermedad al-canza rangos epidmicos y constituye la primera causa demuerte por tumores malignos (2). Por el contrario enotras regiones geogrficas la incidencia de esta enferme-dad es baja (Amrica del Norte, Oeste de Europa, Austra-lia, Nueva Zelanda e Israel). Estas diferencias han sido enparte atribuidas a factores ambientales como alimenti-cios, referidos a la conservacin y preparacin de los ali-mentos, e infecciosos, en relacin con la incidencia de in-feccin por H. pylori en la poblacin. Tal es la posibleinfluencia de estos factores, que la progresiva disminu-cin en la tasa de incidencia y de mortalidad de esta en-fermedad observada desde la dcada de los 30 hasta losltimos 10 aos, se ha atribuido a los cambios dietticosy de conservacin de los alimentos (3-5).

No obstante este cambio en los factores ambientales noexplica por completo las variacines geogrficas conocidasni la diferente evolucin y pronstico de la enfermedad.

Actualmente, se acepta que la carcinognesis gstricaes un proceso progresivo en el que intervienen mltiplesfactores tanto ambientales y epidemiolgicos como gen-ticos, y cuya interaccin parece influir no slo en el desa-rrollo sino tambin en la progresin de la enfermedad (6).

2. FACTORES CARCINOGNICOS

2.1. Factores ambientales

En los ltimos aos y puesto que el cncer gstricocontina siendo uno de los tumores malignos ms fre-

cuentes en la poblacin mundial muchos estudios hancentrado su atencin en identificar factores de riesgo am-bientales que justifiquen su amplia variacin geogrfica.

Factores alimenticios

Las poblaciones con un alto consumo de sal, alimentosahumados, picantes o grasas fritas presentan una elevadatasa de incidencia de adenocarcinoma gstrico indicandosu posible papel en la carcinognesis (5,7-10).

Alimentos o agua rica en nitritos, la alta ingesta de car-bohidratos y el poco acceso y consumo de fruta, verdurafresca, leche, vitaminas A, C y E y selenio parecen incre-mentar el riesgo de desarrollar cncer gstrico (3,5).

Los factores clsicamente considerados carcinogni-cos como el tabaco, el alcohol o la toma de te verde, pre-sentan todava en la literatura resultados poco consisten-tes (6,11).

Cabe destacar en la actualidad, el incremento progresi-vo en los pases industrializados del adenocarcinoma gs-trico de localizacin cardial frente al predominio de losdistales y prcticamente la ausencia de los proximales enlos pases en vas de desarrollo (9,10). Estas diferenciasse atribuyen a una mayor incidencia de la enfermedad porreflujo gastro-esofgico en los pases desarrollados en re-lacin con la dieta y el aumento de la tasa de obesidad.

Tambin el consumo de forma crnica de antisecretorestipo inhibidores de la bomba de protones favorece latransformacin de los nitratos de la saliva a nitritos, agen-tes que favorecen la enfermedad (12).

Infeccin por H. pylori

A comienzos de los aos 80 se descubri en las biop-sias de la mucosa gstrica de pacientes con gastritis y ul-cus pptico la presencia de una bacteria que inicialmentefue denominada Campylobacter piloridis (13) y poste-riormente C. pylori. En la actualidad se denomina Heli-

Carcinognesis gstrica

S. de la Riva, M. Muoz-Navas y J. J. Sola1

Servicios de Aparato Digestivo y 1Anatoma Patolgica. Clnica Universitaria de Navarra. Pamplona

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

9/12

cobacter pylori. Se trata de una bacteria con forma de es-piral que pertenece al grupo de los grmenes gram-nega-tivos y que utiliza una gran variedad de estrategias paralograr sobrevivir en el medio cido.

La infeccin crnica porH. pylori conduce al desarro-

llo de una gastritis crnica, mediada por la activacin deuna red compleja de mediadores inflamatorios incluidosIL-8, citoquinas proinflamatorias (IL-1, IL-6, FNT) ypptidos inmunosupresores (IL-10) (14).

A su vez esta inflamacin crnica conduce a alteracio-nes en el ciclo celular favoreciendo la replicacin de lasclulas epiteliales, incrementando la tasa de apoptosis yaumentando la liberacin de sustancias oxidantes. Todoesto en combinacin con la deplecin de las defensas an-tioxidantes predispone a la carcinognesis gstrica poraumentar la probabilidad de mutaciones de ADN (14).

La acumulacin de estas mutaciones puede conducir aldesarrollo de lesiones premalignas e iniciar el proceso de

metaplasia, displasia y adenocarcinoma gstrico (4, 15).Actualmente la infeccin crnica por la bacteriaH. py-lori es considerada como carcingeno del grupo I por laOrganizacin Mundial de la Salud (OMS) (16) y parece

jugar un importante papel en el desarrollo del adenocarci-noma gstrico distal.

Varios estudios clnicos y epidemiolgicos han obser-vado esta asociacin estimndose que el menos el 1% delas infecciones porH. pylori pueden conducir al desarro-llo del cncer gstrico segn la secuencia anteriormenteexpuesta (17), aumentando el riesgo de 2,7 a 12 veces elde la poblacin general (18). De forma global el 8% delos tumores gstricos estn relacionados causalmente por

la infeccin porH. pylori (19).Al igual que la incidencia de la enfermedad, la tasa po-blacional de infeccin porH. pylori presenta una gran va-riacin geogrfica. En general reas con alto riesgo deadenocarcinoma gstrico muestran altas tasas de infec-cin porH. pylori (20,21).

Del mismo modo se ha recogido una incidencia decncer gstrico mayor en poblaciones con nivel socioeco-nmico bajo. Esta observacin parece estar relacionadaen parte con factores alimenticios como menor acceso yconsumo de frutas y verduras frescas y/o una mayor tasade infeccin por H. pylori adquirida a edades ms tem-pranas (22).

En un intento de explicar la mayor asociacin de la in-feccin concomitante porH. pylori con el adenocarcino-ma de tipo intestinal frente al tipo difuso, se ha propuestola existencia de dos vas de actuacin diferentes segn eltipo histolgico de cncer gstrico, con progresivos cam-bios histolgicos en el adenocarcinoma de tipo intestinalque no tienen lugar en el de tipo difuso (23) (Fig. 1).

Infeccin por virus del Epstein Barr (EBV)

Descubierto por Epstein en 1964, es un herpes-virusicosadrico que contiene una doble cadena lineal de

ADN. Fue relacionado por primera vez con el cncer gs-trico en 1990 tras observar mediante PCR e hibridacinin situ la presencia de su material gentico en pacientescon cncer gstrico (24). Su asociacin ha sido encontra-da en numerosos estudios de diferentes regiones geogr-

ficas (25,26).A diferencia delH. pylori, su infeccin ha sido obser-vada por igual en el cncer gstrico de tipo difuso que enel intestinal (27).

Todava se desconoce cul es su mecanismo carcino-gnico. Incluso se ha propuesto la existencia de dos vasde carcinognesis distintas en funcin de la presencia oausencia de la infeccin concomitante por este virus (28).

2.2. Factores genticos

En relacin con la influencia de los factores genticos

en el desarrollo del adenocarcinoma gstrico, se ha obser-vado que el cncer gstrico puede estar presente en fami-lias durante dos o tres generaciones y que adems losmiembros de una familia con antecedentes de adenocar-cinoma gstrico tienen un riesgo incrementado en dos oincluso tres veces el de la poblacin general, implicandouna posible agregacin familiar (29).

Sin embargo los estudios que incluyen a miembros deuna misma familia son limitados y sus resultados se veninfluidos por los factores ambientales, puesto que gene-ralmente los miembros de una misma familia estn bajolas mismas condiciones dietticas y ambientales (29).

Una observacin que implica de manera indirecta el

posible papel de factores genticos en la carcinognesisgstrica, es la mayor asociacin de esta enfermedad conel grupo sanguneo A en comparacin con los otros gru-pos sanguneos. Esta asociacin es ms marcada en varo-nes y en el tipo histolgico difuso frente al intestinal (5,9,29).

2.3. Condiciones precursoras

Determinados cambios histolgicos de la mucosa gs-trica sana aumentan significativamente el riesgo de desa-rrollar un adenocarcinoma gstrico.

Entre ellos cabe destacar:

Gastritis crnica atrfica

Lesin precancerosa que se encuentra presente en el90% de los adenocarcinomas gstricos. En general re-quiere un largo periodo de evolucin hasta el desarrollodel cncer gstrico. En la mayora de los estudios en losque el seguimiento de los pacientes fue superior a los 10aos, el riesgo de desarrollar cncer gstrico fue de 1 porcada 150 pacientes por ao, incrementndose este riesgoal 10% despus de los 15 aos de seguimiento (30,31).

Vol. 96. N. 4, 2004 CARCINOGNESIS GSTRICA 273

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2004; 96(4): 265-276

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

10/12

Su mecanismo carcinognico parece partir de la disminu-cin de la secrecin de cido clorhdrico y pepsina, aumen-tando el pH gstrico, lo que favorece la proliferacin de gr-menes reductores de los nitratos de la dieta. La formacin denitrosamidas y nitrosaminas junto con algunos factores die-

tticos como son la ingesta excesiva de sal o la ingesta inade-cuada de vegetales y fruta fresca pueden inducir mutacionesdel ADN en las clulas epiteliales favoreciendo la apariciny progresin de cambios tisulares como metaplasia intestinaly displasia, considerados lesiones premalignas (4,32).

Anemia perniciosa

Condicin que cursa con atrofia gstrica y que aumen-ta el riesgo de desarrollar cncer gstrico (33) aunqueslo el 5-10% de estos pacientes lo desarrollan (31).

Gastrectoma parcial

Los pacientes con patologa benigna sometidos a estaciruga tienen un riesgo incrementado de desarrollar ade-nocarcinoma gstrico a partir de los 10 aos de la interven-cin (34). Entre los 15 y 25 aos tras el procedimiento elriesgo se incrementa un 50 y 70% respectivamente (31).

Enfermedad de Mntrier (gastropata hipertrfica)

El riesgo de desarrollar cncer gstrico a partir de este

cambio tisular es alto, situndose entre el 10-15% en al-gunas series, pero puesto que ya de por s se trata de unacondicin extremadamente rara, este porcentaje de trans-formacin resulta insignificante (35).

Plipos adenomatosos

Los plipos se encuentran con relativa frecuencia en lamucosa gstrica. Se clasifican en dos tipos:

No neoplsicos: no presentan capacidad degenerati-va (hiperplsicos, hamartomatosos, inflamatorios o hete-rotpicos).

Neoplsicos: adenomas. Constituyen el 15-20% delos plipos encontrados en la mucosa gstrica. Poseenpotencial neoplsico con una incidencia de malignizacinque oscila entre el 5-15% de los adenoma tubulares y el15-75% de los adenomas vellosos. La tendencia a la ma-lignizacin est directamente relacionada con el tamaodel plipo y con la presencia o grado de displasia (36).

lcera pptica

La posibilidad de transformacin de una lcera pp-tica benigna en maligna est todava en discusin con

opiniones discordantes al respecto. Aunque la mayorade los autores niegan esta posibilidad, se debe tener encuenta el papel que parece desarrollar la infeccin por

H. pylori en el proceso de la carcinognesis gstrica(37).

Esfago de Barrett

El aumento de la incidencia del adenocarcinomagstrico cardial en los pases indutrializados parece es-trechamente relacionado con el aumento de la inciden-cia de la enfermedad por reflujo gastro-esofgico y delesfago de Barrett (38,39). Todava son necesarios es-tudios ms amplios para determinar otros factores queintervengan en su desarrollo y de esta manera poderestablecer si realmente el cncer gstrico proximal esuna entidad con diferente etiopatogenia y evolucin

que el distal.

2.4. Factores moleculares

Aunque hay suficiente evidencia de que las altera-ciones genticas juegan un papel importante en el pro-ceso multipaso de la carcinognesis gstrica y en suprogresin, el amplio nmero de factores analizados ylos diferentes resultados obtenidos no permiten por elmomento establecer conclusiones definitivas (9,40-42). Lo que s parece claro es que la conversin de c-lulas normales gstricas en tumorales es un proceso

lento y progresivo con acumulacin de mltiples alte-raciones moleculares, que se ha querido equiparar alproceso de carcinognesis del cncer colorrectal. Estaacumulacin de cambios genticos incluye mutacionesy/o amplificacin-sobre-expresin de oncogenes (c-Ki-ras, c-erb-B2, K-sam, hst/int-2, c-met y c-myc),inactivacin de genes supresores de tumor (p53, APC,DCC y RB1), y alteracin de microsatlites (prdidade heterozigosidad o inestabilidad de microsatlites)en una o ms regiones cromosmicas como 1p, 5q, 7q,12q, 13q, 17p, 18q e incluso en el cromosoma Y(40,43,44) (Tabla I).

Los resultados de los diferentes estudios de anlisis

molecular en el cncer gstrico han puesto de manifiestola posible existencia de dos vas de carcinognesis distin-tas en funcin del tipo histolgico de adenocarcinoma di-fuso o intestinal (45-49). El cncer gstrico de tipo intes-tinal parece tener relacin con la existencia de cambiostisulares en la mucosa gstrica tipo metaplasia intestinaly presenta semejanzas con la evolucin molecular delcancer colorrectal (47). Se desarrolla a travs de un pro-ceso que se inicia con la gastritis crnica y se continacon la gastritis atrfica, la metaplasia intestinal y la dis-plasia (4). Por otro lado parece que la historia natural delcncer gstrico de tipo difuso prescinde de esta evolucinmultipaso (46,50-52).

274 S. DE LA RIVA ET AL. REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid)

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2004; 96(4): 265-276

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

11/12

3. MODELO ACTUAL DE CARCINOGNESIS

La clasificacin histolgica de Lauren (1965) del cn-cer gstrico en difuso e intestinal es la ms frecuentemen-te utilizada por la mayora de los autores (53).

Estos dos tipos histolgicos de cncer gstrico proba-

blemente reflejan no slo las diferencias morfolgicasque permiten su clasificacin, sino tambin distintas ca-ractersticas clnicas, epidemiolgicas y patognicas.

Por todo ello se ha propuesto la existencia de dos vasde carcinognesis diferentes segn el tipo histolgico decncer gstrico con distinta influencia de los factores am-bientales y variacin en la presencia y predominio de lasalteraciones moleculares.

El tipo intestinal, como ya se ha comentado anterior-mente, parece desarrollarse a partir de sucesivos cambiostisulares de forma similar a la va de carcinognesis delcncer colorrectal. OConnor y cols. (54), Watanabe ycols. (24) y Correa (4) propusieron, en relacin con los

factores ambientales, un modelo de carcinognesis gstri-ca en espiral, de manera que un acmulo del nmero delos factores de riesgo ambientales supona un tiempo dedesarrollo ms corto, y su disminucin un alargamientodel tiempo de evolucin (Fig. 2).

Adems y del mismo modo que los autores anterio-mente citados, Yasui y cols. (42) recogieron de la litera-tura todos los factores moleculares analizados e implica-dos en la carcinognesis gstrica, en un intento deequiparar la carcinognesis gstrica al proceso carcino-gnico colorrectal. Debido a las diferencias observadasentre los dos tipos histolgicos de adenocarcinoma gs-trico, plantearon la posibilidad de la existencia de dos

vas de desarrollo distintas con la presencia y predomi-nio de diferentes alteraciones moleculares (Fig. 3).

Lo que s parece claro es que en la carcinognesis deladenocarcinoma gstrico de tipo intestinal acontecenuna serie de cambios tisulares que pueden progresar ha-

cia la malignidad y que se consideran preneoplsicos.Estas lesiones son la metaplasia intestinal y la displasiaepitelial.

Por el contrario el tipo difuso de adenocarcinoma gs-trico no parece seguir este proceso multipaso de desarro-llo y aparentemente se inicia desde una mucosa gstricasana sin cambios tisulares previos (34).

4. LESIONES PREMALIGNAS

Se definen como aquellos cambios tisulares que pue-den progresar a la malignidad y que se encuentran impli-

cados en la carcinognesis gstrica.Metaplasia intestinal. Definida como presencia de epi-telio diferenciado similar al del intestino delgado. Se cla-sifica segn caractersticas morfolgicas e histoqumicasen:

Metaplasia intestinal completa (tipo I).Metaplasia intestinal incompleta de intestino delga-

do (tipo II) o colnica (tipo III).As, en la metaplasia intestinal tipo I y tipo II las c-

lulas caliciformes producen sialomucinas, en tanto queen la de tipo III estas clulas producen sulfomucinas(55, 56). Aunque parece existir una asociacin entre lapresencia de metaplasia intestinal y el desarrollo de

cncer gstrico, esta lesin premaligna tiene poca im-portancia predictiva. La metaplasia intestinal tipo I serelaciona con baja incidencia de presentacin de cncergstrico en tanto que la metaplasia tipo III tiene un ries-go de 2,7 a 5,8 mayor de desarrollar un cncer gstrico(57,58).

Displasia epitelial. Caracterizada por la presencia deuna serie de alteraciones histolgicas como son la ati-pia celular con pleomorfismo, aumento de clulas indi-ferenciadas y disposicin anmala de criptas y glndu-las.

La displasia epitelial gstrica generalmente ocurre en elcontexto de una gastritis crnica atrfica y suele acompa-

arse de metaplasia intestinal. Con frecuencia se encuen-tran reas de displasia alrededor de los adenocarcinomasgstricos y por lo tanto parece clnica y patolgicamenterelacionada con el cncer gstrico. Mientras que en la ma-yora de los casos, la displasia leve o moderada tiende aregresar o a permanecer estable, la displasia moderada yfundamentalmente la grave estn frecuentemente asocia-das con el desarrollo de adenocarcinoma gstrico (59)(Fig. 4).

De forma global, en un 10% de los pacientes la displa-sia epitelial puede progresar a cncer gstrico en el cursode 5 a 15 aos, pero en la mayora de los pacientes estadisplasia regresa o permanece estable (60).

Vol. 96. N. 4, 2004 CARCINOGNESIS GSTRICA 275

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2004; 96(4): 265-276

Tabla I. Principales alteraciones genticas en la carcinogne-sis y progresin del cncer gstrico

Genes Locus Alteracionescromosoma geneticas

Oncogenes

K-ras 12p12,1 Mutacinc-erb-B2 17q21-q22 Amplificatinhst-1 11q13,3 Amplificatin

int-2 11q13 Amplificatin

met 7q31 Amplificatin

Myc 8q24 Amplificatin

Genes supresores de tumor

p53 17p13,1 LOH*, Mutacin

APC 5q21 LOH*, Mutacin

DCC 18q21 LOH*

RB1 13q14,2 Mutacin

E-cadherin 16q22,1 Mutacin

Prdidad de heterocigosidad 1p,5q,7q,12q, LOH*

13q,17p,18q, Y

LOH: Prdida de heterozigosidad.

-

7/28/2019 Carcinogenesis CA Gastrico

12/12

5. CONCLUSIN

La carcinognesis gstrica en un proceso complejo ylento en el que parecen intervenir mltiples factorestanto ambientales como moleculares. Las diferencias

geogrficas existentes en cuanto a la incidencia, evolu-cin y pronstico del adenocarcinoma gstrico parecenen parte relacionadas con los diferentes y particularesfactores ambientales a los que est expuesta la pobla-cin (alimenticios e infecciosos). Debido a su ms queprobable implicacin, estos factores han sido los msfrecuentemente analizados con resultados concluyentesen relacin al acceso y consumo de determinados ali-mentos, su conservacin y su preparacin. La infeccinporH. pylori en la poblacin es otro de los factores im-plicados en el desarrollo del cncer gstrico siendo

considerado en la actualidad como carcingeno delgrupo I por la OMS.

En cuanto a los factores moleculares, estn cobrandocada vez mayor importancia en la carcinognesis gstrica,

jugando un importante papel en el desarrollo de esta en-

fermedad. La acumulacin de alteraciones molecularesparece influir en el inicio y progresin del adenocarcino-ma gstrico aunque todava no est del todo bien estable-cida su secuencia carcinognica. Lo que parece claro esque esta secuencia vara segn el tipo histolgico del ade-nocarcinoma gstrico. Por este motivo, actualmente seconsidera que la clasificacin del adenocarcinoma gstri-co segn Lauren, no slo refleja diferencias histolgicas,sino tambin epidemiolgicas, clnicas y pronsticas im-plicando la posibilidad de la existencia de dos vas de car-cinognesis diferentes que estn todava por establecer.

276 S. DE LA RIVA ET AL. REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid)