THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

-

Upload

cecilia-acuin -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

1/77

Elsevier Editorial System(tm) for The Lancet

Manuscript Draft

Manuscript Number: THELANCET-D-10-04958R2

Title: Maternal, neonatal and child health: Now (more than ever) for Southeast Asia

Article Type: Invited Series

Corresponding Author: Dr. Cecilia Santos Acuin,

Corresponding Author's Institution: University of the Philippines National Institutes of Health

First Author: Cecilia S Acuin

Order of Authors: Cecilia S Acuin; Geok Lin Khor; Endang L Achadi; Tippawan Liabsuetrakul; Thein

Thein Htay; Rebecca Firestone; Zulfiqar A Bhutta, PhD

Abstract: While maternal and child mortality are on the decline in Southeast Asia, the region is witness

to major disparities across and within its ten member countries, and greater equity will be key to

achieving the MDGs. We used comparable cross-national data sources to document mortality trends

from 1990 in a standardized approach and to assess major causes of maternal and child deaths. We

present inequalities in intervention coverage by two common measures of wealth quintiles and

rural/urban status. Case studies of mortality reduction in Thailand and Indonesia present the mixed

picture of success within this diverse region and point to some of the factors that may be capitalized on

to accelerate progress in the future. We developed a Lives Saved Tool (LiST) analysis for the region as a

whole and for country subgroups defined by mortality trends to estimated deaths averted by cause and

intervention at varying coverage levels. We found three major patterns of maternal and child mortality

reduction: 1) early, rapid downward trends- Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand; 2) initially high

declines sustained by Vietnam but faltering in Philippines, Indonesia; 3) high initial rates with a

downward trend that require more focus to accelerate - Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos. High achievers inthe region point to early declines before rapid economic growth, suggesting that economic

development provides an important context that must be coupled with broader health system

interventions. Increasing coverage will have a significant impact on maternal deaths by unsafe

abortion, hypertensive diseases and postpartum hemorrhage , neonatal deaths caused by pneumonia/

sepsis and birth asphyxia and child deaths caused by infectious diseases. These actions will require

consideration of health system contexts, and a regional push through ASEAN may provide greater

policy support to achieve MNCH goals.

Funding

The Rockefeller Foundation and China Medical Board provided funds that allowed the authors of this

paper to meet and to access research assistance.

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

2/77

1

Title: Maternal, neonatal and child health: Now (more than ever) for Southeast Asia

Order of Authors: Cecilia S Acuin; Geok Lin Khor; Tippawan Liabsuetrakul; Endang L Achadi; Thein

Thein Htay; Rebecca Firestone; Zulfiqar A Bhutta,

Key messages

Southeast Asia has sustained substantial reductions in maternal, neonatal and child mortalitysince 1990, but this progress has been uneven. Mortality reductions in some countries havebeen the result of trajectories of rapid decline begun well before the MDG period. Others have

succeeded in acerbating progress since 1990s, but some countries continue to struggle.

Causes of death suggest a mortality transition in maternal deaths in the region. Child deaths areprimarily due to the persistence of neonatal causes along with key preventable factors in thepostneonatal period

Disparities in intervention coverage are most acute in the countries with the lowest interventioncoverage overall

Despite the mixed picture, some countries stand out as success stories. Suggested key factorsinclude the ability to link MNCH interventions to broader health system investments and totarget access to rural and disadvantaged populations

Increasing coverage to 60% will have a significant impact on maternal deaths caused by unsafeabortion, hypertensive diseases and postpartum hemorrhage and neonatal deaths caused by

pneumonia/sepsis and birth asphyxia. While MNCH may have no quick solutions in the region,coordinated expansion of proven effective interventions can contributed to greater mortality

reductions

There is a need for stronger regional cooperation through ASEAN to support countries that needto accelerate progress to meet the MDGs

Abstract: While maternal and child mortality are on the decline in Southeast Asia, the region is witness to major

disparities across and within its ten member countries, and greater equity will be key to achieving the MDGs. Weused comparable cross-national data sources to document mortality trends from 1990 in a standardized

approach and to assess major causes of maternal and child deaths. We present inequalities in interventioncoverage by two common measures of wealth quintiles and rural/urban status. Case studies of mortality

reduction in Thailand and Indonesia present the mixed picture of success within this diverse region and point to

some of the factors that may be capitalized on to accelerate progress in the future. We developed a Lives SavedTool (LiST) analysis for the region as a whole and for country subgroups defined by mortality trends to

estimated deaths averted by cause and intervention at varying coverage levels. We found three major patterns of

maternal and child mortality reduction: 1) early, rapid downward trends- Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand;

2) initially high declines sustained by Vietnam but faltering in Philippines, Indonesia; 3) high initial rates with a

downward trend that require more focus to accelerate - Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos. High achievers in the region

point to early declines before rapid economic growth, suggesting that economic development provides an

important context that must be coupled with broader health system interventions. Increasing coverage will have a

significant impact on maternal deaths by unsafe abortion, hypertensive diseases and postpartum hemorrhage ,

neonatal deaths caused by pneumonia/ sepsis and birth asphyxia and child deaths caused by infectious diseases.These actions will require consideration of health system contexts, and a regional push through ASEAN may

provide greater policy support to achieve MNCH goals.

Funding

The Rockefeller Foundation and China Medical Board provided funds that allowed the authors of this

paper to meet and to access research assistance.

nuscript

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

3/77

2

Introduction

Southeast Asia has achieved substantial reductions in child and maternal mortality within a relativelyshort period of time, but these achievements are unevenly distributed among the countries in the region.

Of the ten countries in the political coalition known as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations

(ASEAN), only three have infant and child mortality rates below 10/1000 live births, namely Brunei,Singapore and Malaysia. Infant and under-five mortality in Thailand and Vietnam have declined

dramatically to below 15, but the Philippines and Indonesia have seen a leveling off of rates in the 30s

and 40s. Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos still see mortality levels comparable to their neighbors morethan two decades ago and rank among the highest for Asia (1).

The United Nations estimates that each year approximately 350,000 women die as a result of

pregnancy or childbirth (2), as do nearly 9 million children below 5 years (3). Southeast Asiacontributed approximately 18,000 maternal (2) and 400,000 child (3) deaths to this global burden in

2008. Two of the seven countries with the highest maternal mortality ratios outside of sub-Saharan

Africa are Laos and Cambodia, while Indonesia is among the countries accounting for 65% of all

maternal deaths worldwide. While Southeast Asia, as a region, may achieve the child mortality

reductions set by the United Nations Millenium Development Goal 4 (MDG4), Cambodia andMyanmar have been rated as showing "insufficient progress" (4). Declines in Laos, Indonesia and the

Philippines are also faltering. Similarly, while all countries demonstrate declines in maternal deaths, therates of decline for Indonesia, Myanmar and the Philippines have slowed considerably.

Effective and affordable technology to reduce the majority of maternal, newborn and child deaths is athand (5, 6, 7, 8), so why has progress been so uneven? This paper focuses on a region, collectively the

9th largest economy in the world, whose performance and achievements are often hidden by larger

states like India or China and UN agency regional groupings that do not take into account historical and

geo-political ties within ASEAN (28).

Southeast Asia as a region has received markedly little attention in recent efforts to revitalize and

strengthen the MNCH policy agenda, despite the complexity of national trends, including thesignificant burden of morbidity and mortality in several countries and the existence of documented

successes (31). As Southeast Asia becomes more integrated economically, there is a growing need to

take stock of this major unfinished agenda and identify policy options for sustaining if not accelerating

the pace of mortality reduction.

This paper aims to critically review the regions achievements in maternal and child mortality reduction

and point to key factors that explain success and challenges in reaching these goals amidst competing

global, regional and national health problems. We first report on patterns of mortality reduction within

Southeast Asia as well as major causes of maternal and child deaths in the context of MDGs 4 and 5.We investigated two country cases to illustrate the significant variations in mortality reduction. Finally,

we used an analysis of the deaths to be averted through expanded coverage to identify more effectiveapproaches for pursuing maternal, neonatal and child health in Southeast Asia.

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

4/77

3

Methods

Data sources

For the ten countries considered here, we reviewed estimates from national data sources includingDemographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), as well as

global datasources from UNICEF, WHO, and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME)(webTable 1). We present country-specific estimates on maternal, infant, and under-five mortalityrates from recent UN MDG reports (2, 3), as these estimates enable cross-country comparisons on

trends in mortality using replicable estimation methods that seek to reduce sources of non-sampling

error. These estimates tend to be more conservative in the rate of decline than IHME estimates. Basedon growing awareness of the burden of neonatal mortality, we sought comparable estimates of trends

disaggregating neonatal (death within the first 28 days following birth) and postneonatal (death

between 28 days and one year following birth) mortality. As UN models do not have neonatal time

trends for all countries of the region, we present estimates from IHME (10). We present estimates oncauses of neonatal and child deaths based on standardized methods for estimating the distribution of

causes of child deaths (11). We have compiled estimates of causes of maternal deaths from Countdown

2015 country reports (4) and WHO (12) and we used annual State of the Worlds Children reports (13)

to review standard assessment of nutrition trends (web Appendix Fig 2). Data from DHS (14) andMICS (15, 16) were evaluated to assess existing intervention coverage within the region, with these

data sources providing the ability to disaggregate coverage estimates by wealth quintile and rural/urban

status (17-20) to unpack country average and asses program coverage among disadvantagedpopulations. Regional estimates were calculated using country-level data from the specific source cited,

unless otherwise indicated.

Analysis

Case studies were developed to test the contribution of health sector inputs to mortality reductions.

Thailand and Indonesia were selected as cases, as high and lower achievers, and we focused onmaternal and neonatal mortality as outcomes sensitive to health system development. National data

were used for case studies in order to extend the analysis to the period prior to the MDG baseline year

(38, 42). For the case studies, data was fitted to a quadratic equation (log 10MMR or log10NMR =Intercept + linear effect of year+ quadratic effect of year) as well as a linear equation (log 10 MMR or

log10NMR= Intercept + linear effect of year) to determine whether declines in maternal mortality could

be attributed to program changes or temporal trends.

We calculated potential deaths to be averted through increasing population coverage of the

interventions proven to be effective in reducing maternal, neonatal and child mortality using the Lives

Saved Tool (LiST) (21,49). LiST operates within the Spectrum modelling platform, initially developed

to project demographic change and complemented by modules to model the impact of family planningand HIV/AIDS interventions (50). The model yields estimates of deaths averted by cause and

intervention for user-specified intervention coverage levels, based on inputs of demographic

projections, numbers of maternal and child deaths, data on the distribution of deaths by cause,intervention effectiveness, and data on local health status (6, 22, 23, 24). The tool has been previously

used for analysis of impact of intervention packages on maternal and child survival in South Africa (25)

and sub-Saharan Africa, but this is a first application in Southeast Asia (26). For this analysis, weassessed all of the MNCH interventions included in LiST (51). The interventions and their

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

5/77

4

effectiveness estimates are shown in webtable 2. Values for the effectiveness of interventions weredeveloped through a standardized review process using established criteria to determine which

interventions to include based on levels of evidence (51). The analysis was conducted for all ten

countries and then for three subgroups of countries based on observed patterns of mortality reduction:

subgroup 1 (Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand); subgroup 2 (Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam);subgroup 3 (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar). We assessed potential lives saved at three hypothetical

coverage levels: 60%, 90% and 99%.

Results

Patterns of Mortality Reduction

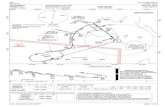

Reduction in maternal, infant and child mortality (Fig1a-Fig 1c, data not shown for Brunei andSingapore) in Southeast Asia reflect the diversity of this region, presenting three divergent patterns (27,

28). The first pattern reflects countries achieving low mortality rates between 1990, the MDG baseline

year, and 2008 in Brunei, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand. In 1990, maternal mortality ratios in these

countries were well below 100/100,000 live births, and infant and under-five mortality rates werealready at or below 20/1000 live births. These most economically advanced countries in the region

have also invested in their health systems over time.

A second, less distinct, pattern, seen in the Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam, starts with relativelyhigh mortality rates and ratios in 1990, fairly large initial reductions (except for Indonesia's maternal

mortality ratio) that somewhat faltered after 2000 in Indonesia and the Philippines. In contrast, Vietnam

witnessed accelerated mortality reductions during this period, with mortality rates and ratios beginning

to come close to those of Thailand.

The third pattern, observed in Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar has very high levels at the beginning of

1990, followed by sustained reductions from 1990 to 2005 with the exception of Cambodia's maternal

mortality ratio. These three countries, which are on the UN list of least developed countries, continue to

experience high maternal, infant and child mortality.

Plotting maternal mortality reductions against Gross National Income (GNI) per capita (Web Appendix

Fig 1a) indicates that while countries with high maternal mortality achieved reductions in mortality astheir GNI per capita increased, some of the most dramatic declines in mortality took place earlier than

the rapid rise in GNI. Thailand's rapid maternal mortality reductions occurred pre-1990. As maternal

mortality declined to levels around 100, smaller reductions take place even as GNI continues to

improve. Similar patterns are observed for infant and under 5 mortality vs GNI per capita plots (WebAppendix Fig 1 b and c).

Neonatal and Postneonatal Mortality Reductions

Disaggregating infant mortality reduction between 1990 and 2010 into neonatal and postneonatal (Fig2) indicates that the largest declines in infant mortality over time were mainly due to substantial

postneonatal mortality reductions, as seen in Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand. The Philippines and

Indonesia had neonatal and postneonatal reductions comparable to Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.Although starting with comparably lower baseline mortality levels in 1990, rates of decline in these two

countries were not sufficiently accelerated during the MDG period. Reductions in infant mortality in

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

6/77

5

Brunei and Singapore stem from larger proportions of decline in neonatal deaths, a pattern similar toother high income countries (29).

The slower rates of decline for neonatal mortality for 8 of 10 ASEAN countries is a cause for concern.

Interventions for reducing neonatal mortality are more closely linked to maternal interventions in termsof policy and program implementation and may not be as noticeably tracked towards their impact on

under-5 mortality. The Philippines, which is considered to be "on track" in achieving child mortality

reductions (4), has the lowest reduction in neonatal mortality in the region, lower than Cambodia or

Myanmar, which have been identified as showing "insufficient progress" towards achieving MDG 4.

Causes of Mortality

The distribution of maternal mortality causes (Fig 3a) reflects the significant variations in health statusand health system development seen within the region. Haemorrhage is a leading cause of death, likely

indicative of delays in attaining emergency obstetric care. Hypertensive disorders contribute to about

one in every six maternal deaths in Southeast Asia and suggest a different causal pathway more

comparable to developed country settings. The proportion of other indirect causes may indicate thestill significant burden of infectious disease within the region and the impact of malaria and HIV on

maternal health (30). Unsafe abortion is a factor in almost one-tenth of maternal deaths. These patternsreflect a causal transition in maternal mortality as the overall risk of maternal death declines, and theywill influence the extent to which interventions, both as single modalities or included in a package, can

be predicted to avert deaths. (12).

Differential rates of child mortality reduction can be attributed in part to variations in causes of death

(Fig 3b). Neonatal conditions contributed approximately 40% of child mortality, accounting for the

single largest proportion of preventable deaths, even as a number of the ASEAN countries are

successfully reducing their postneonatal and child mortality burdens. Infectious diseases includingpneumonia, diarrhea and others, still account for almost half of child deaths, reflecting considerable

scope for continued reductions in child mortality (11).

Within Country Disparities in Intervention Coverage

Inequalities are substantial across countries of the region, but also within, as shown by the currentscope of intervention coverage by income and rural/urban sub-groups (Fig 4), considering antenatal

care coverage, use of skilled birth attendance (SBA), DPT and measles vaccination along with use of

oral rehydration therapy, all key to the development of a continuum of care (4, 7).

Laos remains substantially lower than other countries on overall program coverage and far from a 60%

coverage level even for the most well-off groups. Antenatal care coverage is most widespread, being

close to or above 90%, in countries other than Laos and Cambodia, for the most well-off and urbanareas, suggesting that there is scope to effectively scale up prenatal interventions that can avert

maternal deaths. Vaccination coverage varies widely, although several countries in the region are

GAVI-eligible and have received substantial financial and policy support likely to lead to increases invaccination coverage over time.

Laos and Cambodia present the greatest disparities in program coverage. Vaccination levels for the

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

7/77

6

wealthiest quintile are comparable to those of the other SEA countries, but they are well below 50%amongst the poorest households. The countries represented in Fig 4 demonstrate relatively low

coverage of skilled birth attendance (except Thailand) with inequality particularly acute in Laos,

Cambodia and the Philippines. Skilled birth attendance may be viewed as one indicator of broader

health system development, and the generally low coverage coupled with a high degree of inequalityilluminates the need for more comprehensive and coordinated health system strengthening in the region

overall (31). These patterns also point to the necessity of targeting the most vulnerable populations andmaintaining attention to equity while scaling up program coverage (32).

Case studies: Thailand and Indonesia

We look in more depth at two countries with diverging experiences of mortality reduction to understand

potential determinants. Thailand's maternal mortality reduction began in the 1960s (Fig 5) at a time

when skilled birth attendants, primarily midwives, were systematically trained and deployed to

community hospitals (35-37). At the time of Alma Ata, Thailand's maternal mortality ratio was alreadybelow 200 and continued to drop even further in the 1980s as the Thai economy took off and a health

care insurance program for low-income populations was introduced along with specific safe

motherhood interventions. Another round of health system reforms and MNCH interventions were

introduced in the early 2000s, including universal health coverage.

Coordinated health policy support through successive national plans provided a context and

investments to stimulate structural, financial and social capacities to deliver services, particularly in the

district health system (38-40). Mandatory rural service for medical graduates has provided a stablehuman resource base within community hospitals (35).

Using a log linear model, no single program could explain the decline in maternal mortality between

1960 and 1995, suggesting that the accelerated decline may be due to multiple developments. However,model fit after the 1997 economic crisis was not as good compared to earlier time periods. There was

an increase in maternal mortality from 1997 to 2000 followed by a steady decline. This was in parallel

with economic recovery and the introduction of universal coverage for health insurance and the MCHbroad & healthy Thailand and Saiyairak programs (38-40). For this relatively short period, it is difficult

to evaluate the effect of any intervention programs.

The systematic deployment of community-based health personnel took place in Indonesia (41) about adecade later than in Thailand in the 1970s. Major, targeted safe motherhood initiatives were introduced

in the late 1980s, but by that time Indonesia's maternal mortality ratio was about nine times higher than

that of Thailand (Fig 6) (14, 42). A village midwife program was put in place between 1989 - 1996, butthe comparatively rapid training and deployment of 54,000 village midwives may have compromised

quality of care (41).

Access to care in Indonesia varies by geography, rural/urban, poverty and education. Unlike inThailand where the provision of skilled birth attendants was followed by increasing facility and referrallevel capacities, in Indonesia not all health centers can provide basic obstetric care. About 40% of

district hospitals do not have an obstetrician (41), indicating limited provision of the 24-hour

continuum of care necessary for dealing with emergency situations. A fragmented and devolved healthsystem has challenged the capacity to sustain a comprehensive and concerted focus on maternal and

child health.

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

8/77

7

Reductions in neonatal mortality (Fig 7) for the two countries mirror reductions in maternal mortality.Interventions to reduce neonatal mortality require more from health systems than either a maternal or

child program alone (29). In Thailand, neonatal interventions have been linked with maternal programs

(35, 39, 40), but this has not been documented in Indonesia.

Maternal and neonatal mortality reductions in Thailand and Indonesia occurred in the context of rapid

economic growth in both settings along with widespread increases in education levels and in gender

equity (43). Although these factors may have influenced levels of success, other determinants ofmortality have been at play. Policy implementation in Thailand has been multi-sectoral, involving Thai

royalty and different ministries, including finance. Investments in primary health care in the 1970s

have reaped dividends in the long term (31). However, geographic and demographic context likelyalso play a role. At the time of its rapid maternal mortality reduction in the 1970s, Thailand had a

smaller, more circumscribed population compared to the larger and more dispersed Indonesian

population and this difference may have critically determined physical access, a bottom line

requirement for program coverage.

Lives Saved Tool (LiST) Analysis

We investigated the potential impacts of expanding program coverage through a LiST analysis of theASEAN region as a whole, and for subgroups based on the mortality reduction patterns described

earlier.

ASEAN regional averages are closer to those of subgroups 2 and 3, where the bulk of the population

and the higher mortality rates are (Fig 8a). While differences in maternal deaths averted across the

groups are substantial, common trends across the region highlight critical gaps. Expanding coverage ofinterventions for hypertensive disease of pregnancy and safe management of abortions, for example,

will reduce maternal deaths substantially throughout the region, while addressing postpartum

hemorrhage causes will markedly reduce deaths for sub-groups 2 and 3 but not 1.

Counterpart calculations were made for neonatal and child mortality (Fig 8 b and c). Interventions for

birth asphyxia are more likely to avert deaths in subgroups 2 and 3. The high proportion of neonatal

and child deaths averted through interventions for infectious diseases in all subgroups is indicative that

infectious disease remains a challenge for the region as a whole (11).

To focus on universal coverage, now receiving greater attention in other health policy circles (60), we

present the deaths averted at 99% program coverage. At the regional level, universal basic obstetriccare coverage will save about 1in 5 mothers (Table 1), but with universal comprehensive obstetric care

coverage more than half of maternal deaths would be averted. Almost all of these lives saved would be

in sub-groups 2 and 3 where current levels of coverage for these services are low (Fig 4). On the other

hand, basic post-abortion case management will save a higher proportion of mothers in sub-group 1 butmore deaths will actually be averted in sub-groups 2 and 3. The less lives saved in sub-group 1 with

comprehensive as compared to basic abortion care may be due to the already high access to

comprehensive obstetric care that could be utilized for abortion management in this group.

Universal basic obstetric care will avert about 1 in 5 neonatal deaths in subgroup 3 while

comprehensive obstetric care will save almost twice as many lives as basic care will for the region as a

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

9/77

8

whole but particularly for subgroups 2 and 3. Yet even at 99% coverage the maximum proportion ofneonates that could be saved with either of these interventions does not go beyond a quarter of deaths,

indicating the need for other interventions such as those addressing prematurity through antenatal

steroids and providing Kangaroo care.

Interventions directed towards infectious diseases such as diarrhea and pneumonia will, likewise, affect

postneonatal and child deaths mostly in subgroups 2 and 3. A small but noticeable effect on death insubgroup 1 may also be seen when coverage increases to 99%. Preventive measures such as improvingaccess to safe water can contribute substantially to mortality reduction, averting more deaths than

Pneumococcal vaccination will in all the sub-groups.

Discussion

Despite significant improvements in maternal, neonatal and child health since 1990, most notably in

Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam, high mortality, poor coverage and high inequity continue to challengeother countries in the region, such as Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. Improvements in the first three

countries appear to be due to socioeconomic progress in part as well as to a consistent policy focus on

maternal and child health programs and coordinated health systems components (33,44,45), notably a

stable and strategically deployed health workforce coupled with supportive finance mechanisms inThailand and Malaysia. The importance of favorable health systems is highlighted by the Thai case

study which shows that 1) mortality reductions have taken place at modest levels of economic growth,

and 2) no single factor or intervention could account for these reductions. Indonesia shows how similarinterventions applied to a setting with differing system capacities and geopolitical features can result in

differing outcomes.

Thus, while the LiST analysis can estimate the potential impact of interventions given maximum levels

of coverage, the case studies caution us that improving health outcomes is not just about increasing the

amount of money spent in health. Rather, targeted and sustained interventions to reduce the barriers

that prevent the most vulnerable population groups from accessing the interventions they critically needmust be ensured in the long haul. For example, the LiST analysis indicates that providing basic and

comprehensive emergency obstetric care has the potential to avert half of all maternal deaths and about

1 in 6 neonatal deaths in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. However, this may be possible only if carecoverage is rapidly expanded among lower income and rural populations, possibly through sustained

donor investments, given low levels of domestic health spending. In the case of the Philippines and

Indonesia, the two most populous countries in the region, regaining momentum in mortality reduction

in the face of considerable geographic and cultural access challenges may mean correcting inequitableaccess to services through health financing (60).

Despite the varying agendas that countries of the region may need to adopt to complete the unfinished

MNCH agenda, our findings indicate critical areas of common ground. Many key interventions toreduce child deaths have been rolled out at the community level throughout Southeast Asia, but

necessary health service investments that will enable the countries of the region to gain traction on

maternal and neonatal deaths have yet to be fully considered. Access to safe abortion services andmanagement of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy will prevent maternal deaths of these causes

from Singapore to Cambodia. Similarly, all countries in the region see space for expanding coverage of

critical neonatal interventions to prevent pre-term births and neonatal deaths from infection.

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

10/77

9

Our study has several limitations. We have used estimates of mortality reduction from UN agenciesthat may not match national estimates, which use different methodologies; however these estimates are

preferred for cross-country analysis. These estimates for Southeast Asia are still primarily derived

from household surveys and subject to potential error from underreporting and misclassification of

deaths. Only five of the ten countries considered have vital registration systems and not all of thesesystems have valid registration of causes of death (2). The need for better data is acute in Laos and

Myanmar, particularly on maternal mortality, but Malaysias pioneering work in maternal death auditsprovides a potential model for the region (52).

The selection of data sources was largely affected by the availability of comparable, reliable data across

all the ASEAN countries. For example, while we used the more inclusive GNI/capita for WebAppendix Fig. 1, this measurement was not consistently available for the case studies, hence the use of

GDP for the latter.

We were not able to disaggregate LiST estimates into relevant national sub-groups by wealth orrural/urban status. This is important, since the poorest populations are likely to have higher mortality

rates as well as lower levels of intervention coverage, and this could influence estimates (53). Data

limitations restricted our ability to develop this analysis, even as a test case. We have also not analyzed

the costs involved in extending coverage, which we hope to develop in a future study.

A Challenge to ASEAN

Since its formation in 1967, ASEAN has positioned itself as an important hub for economic and socio-

cultural cooperation. Infectious diseases have thus far commanded much of ASEAN's attention in

health matters. Recently, regional focus has begun to shift to other health issues. The ASEAN StrategicFramework on Health Development 2010-2015 (54), which focuses on access to health care services

besides communicable diseases and pandemic preparedness, has also gained regional support.

Given the economic vigour of ASEAN, regional cooperation in health promises to be the key for lessdeveloped members to break free from systems inertia and address the low-lying fruits of maternal and

child health and nutrition. The pivotal role played by ASEAN in stimulating and channeling

international financial aid to tsunami-devastated Indonesia in 2004 and cyclone-stricken Myanmar in2008 testifies to the power of this promise.

But how should this aid be used? ASEAN experience, as distilled in this paper, suggests that effective

interventions to curb maternal and child mortality must be deployed to actively seek out thedisadvantaged populations who are most ravaged by unsafe abortion, hypertensive diseases, postpartum

hemorrhage, pneumonia, sepsis and birth asphyxia. Far from expecting coverage of these programs to

passively diffuse to the very poor, governments must innovatively combine health interventions with

non-health programs such micro-finance schemes and conditional cash transfer mechanisms that haveproven successful in other settings (55, 56).

Achievement of the MDGs at the global level will not happen without individual country efforts. As thedonor community focuses its attention on the burdens of Africa and South Asia, ASEAN countries must

support each other.

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

11/77

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

12/77

11

Economic Differences in Health, Nutrition, and Population in the Philippines (Washington, D.C.:

The World Bank, 2007).

20. Gwatkin D, Rutstein S, Johnson K, E, Suliman E, A, Wagstaff A, and Amouzou A. Socio-

Economic Differences in Health, Nutrition, and Population in Vietnam (Washington, D.C.: The

World Bank, 2007).

21. Plosky WD, Stover J, and Winfrey B. The Lives Saved Tool , A Computer Program for

Making Child and Maternal Survival Projections. December 2009.

22. Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS. The Bellagio Child Survival StudyGroup. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 2003; 362: 65-71.

23. Bhutta ZA, Ahmad T, Black RE, et al for the Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study

Group. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet 2008;

371: 417-440.

24. Boschi-Pinto C, Young M, Black RE. The child health epidemiology reference group

reviews of the effectiveness of interventions to reduce maternal, neonatal and child mortality. Int. J.

Epidemiol. (2010) 39(suppl 1): i3-i6.

25. Chopra M, Daviaud E, Pattinson B, Fonn S, Lawn JE. Saving the lives of South Africa's

mothers, babies, and children: can the health system deliver? Lancet 2009; 374: 835-84626. Friberg IK, Kinney MV, Lawn JE, Kerber KJ, Odubanjo MO, et al. (2010) Sub-Saharan

Africa's Mothers, Newborns, and Children: How Many Lives Could Be Saved with Targeted Health

Interventions? PLoS Med 7(6): e1000295. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.100029527. World Bank. World Bank database. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/

Resources/GNIPC.pdf (Accessed 19 Sept 2010 )28. Virasakdi C, KH Phua, MT Yap, NS Pocock, J Hashim, R Chhem, SA Wilopo and AD

Lopez, Health in Southeast Asia: Diversity and Transitions, Lancet (overview paper, accepted for publication)

29. Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J, and Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million

neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005 Mar 5-11;365(9462):891-900.

30. Coker RJ, Hunter B, Rudge J, Liverani M, Hanvoravongchai P. The emergence of and

response to infectious diseases in South East Asia. Lancet 2011

31. Rohde J, Cousens S, Chopra M, Tangcharoensathien V, Black R, Bhutta ZA, Lawn JE. 30

years after Alma-Ata: has primary health care worked in countries? Lancet 2008:372:950-61.

32. Countdown 2008 Equity Analysis Group, Boerma JT, Bryce J, Kinfu Y, Axelson H, Victora

CG. Mind the gap: equity and trends in coverage of maternal, newborn and child health services in54 Countdown countries. Lancet. 2008 Apr 12;371(9620):1259-67.33. Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P. Equity in maternal and child health

in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ. 2010 Jun;88(6):420-7. Epub 2009 Dec 8.

34. Vapattanawong P, Hogan MC, Hanvoravongchai P, Gakidou E, Vos T, Lopez AD, Lim SS.

Reductions in child mortality levels and inequalities in Thailand: analysis of two censuses. Lancet.

2007 Mar 10;369(9564):850-535. Wibulpolprasert S. Community financing: Thailand experience. Health Policy Plan 1991;

6: 354-360.

36. Van Lerberghe W, De Brouwere V. Of blind alleys and things that have worked: historyslessons on reducing maternal mortality. Studies Health Serve Organ Policy 2001; 17: 733.

37. Bureau of Policy and Strategy, Ministry of Public health. Health Policy in Thailand.

Nonthaburi: Ministry of Public Health, 2009.38. Wibulpolprasert S, editor. Thailand Health Profile 2005-2007. Bangkok: The War Veterans

Organization of Thailand Printing Press; 2007.

39. Pramualratana P, Wibulpolprasert S. Health insurance systems in Thailand. Nonthaburi:

Health System Research Institute, 2002.

40. WHO SEARO. Improving Maternal, Newborn and Child Health in the South-East Asia

Region. Data source: Basic Indicators: Health Situation in South-East Asia, World Health

Organization, South-East Asia Region, 2004.

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

13/77

12

41. Azwar A. Evolution Of Safe-Motherhood Policies In Indonesia. Presented in: IMMPACT

Country Co-ordinating Group & Technical Partners Meeting, Aberdeen, January 2004.

42. Ministry of Health, Indonesia. National Health Surveys 1980 - 2008.

43. Gakidou E, Cowling K, Lozano R, Murray CJL. Increased educational attainment and its

effects on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: a systematic analysis, Lancet

2010; 376: 95974.44. UN Country Team Malaysia. Malaysia, Successes and challenges, Kuala Lumpur: UNDP,

2005.45. Health Policy and Strategy Institute. Measuring Health Systems Performance in Vietnam:

Results from Eight Provincial Health Systems Assessments.

http://www.healthsystems2020.org/content/resource/detail/2515/(accessed September 25, 2010)

46. UNESCAP. Development of Health Systems in the Context of Enhancing Economic Growth

towards Achieving the Millennium Development Goals in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok: ESCAP;

2007.

47. Jordan S, Lim L, Seubsman SA, Bain C, Sleigh A; the Thai Cohort Study Team. Secular

changes and predictors of adult height for 86 105 male and female members of the Thai Cohort

Study born between 1940 and 1990. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010 Aug 30. [Epub ahead ofprint]

48. ASEAN Charter of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

http://www.aseansec.org/21069.pdf(accessed September 22, 2010).49. Institute for International Programs. LiST: The Lives Saved ToolAn evidence-based tool for estimatingintervention impact. http://www.jhsph.edu/dept/ih/IIP/list/index.html (accessed October 30, 2010 )50. Stover J, McKinnon R, Winfrey B. Spectrum: A model platform for linking impact of maternal and child

survival intervention with AIDS, family planning and demographic projections. Int. J. Epidemiol. (2010)

39(suppl 1): i7-i10.

51. Walker N, Fischer-Walker C, Bryce J, Bahl R, Cousens S and writing for the CHERG Review Groups on

Intervention Effects. Standards for CHERG reviews of intervention effects on child survival. Int. J. Epidemiol.

(2010) 39(suppl 1): i21-i31 doi:10.1093/ije/dyq036.

52. Abu Bakar S, Mathews A, Jegasothy R, Ali R, Kandiah N. Strategy for reducing maternal mortality Bulletin

of the WHO 1999; 77: 190-193.

53. Victora CG. Commentary: LiST: using epidemiology to guide child survival policymaking and programming.

Int. J. Epidemiol. (2010) 39(suppl 1): i1-i2 doi:10.1093/ije/dyq044.54. Association of Southeast Asian Nations.http://www.aseansec.org/24938.htm (accessed October 30,2010).

55. Health Microinsurance: A Comparative Study of Three Examples in Bangladesh, by Mosieh Ahmed, SyedKhairul Islam, Md. Abul Quashem and Nabil Ahmed, CGAP working Group on Microinsurance, Case Study No.

13: September 2005.

56. Fiszbein A, Schady N. et al. Conditional Cash Transfers: Reducing Present and Future Poverty.(Washington,

D.C.: The World Bank, 2009).

57. Estimation Methods Used by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation.

http://www.childmortality.org/stock/documents/Methods%20for%20Estimating%20Child%20Mortality_2010.pd

f (accessed October 30, 2010).

58. Wilmoth J, Zureick S, Mizoguchi N, Inoue M, Oestergaard M. Levels and Trends of Maternal Mortality in

the World: The Development of New Estimates by the United Nations.http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/MMR_technical_report.pdf (accessedOctober 30, 2010).

59. Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Blossner M, Black RE. Undernutrition as an underlying cause of child deaths

associated with diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria and measles. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004. 80:193-8.60. Tangcharoensathien V, Patcharanarumol W, Ir P, Aljunid SM, Ghufron Mukti A, Akkhavong K, Banzon E,

Huong DB, Thabrany H, Mills A, Health Financing Reforms in South East Asia: challenges in achieving

universal coverage. Lancet 2010

http://www.aseansec.org/24938.htmhttp://www.aseansec.org/24938.htmhttp://www.aseansec.org/24938.htmhttp://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/MMR_technical_report.pdfhttp://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/MMR_technical_report.pdfhttp://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/MMR_technical_report.pdfhttp://www.aseansec.org/24938.htm -

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

14/77

13

Table 1. Percentage of deaths averted with 99% coverage of selected interventions for ASEAN regionand sub-groups as defined by mortality reduction patterns

Maternal deaths averted (%)

Interventions Sub-group 1 Sub-group 2 Sub-group 3 ASEAN region

Basic emergency obstetric care (clinic) * 19.4 21.5 19.0

Comprehensive emergency obstetric care 1.6 55.1 55.6 52.9

Post abortion case management, basic level 9.2 6.1 6.1 5.8

Post abortion case management,comprehensive level

4.4 10.3 10.3 6.5

Neonatal deaths averted (%)

Basic emergency obstetric care (clinic) * 11.7 17.2 12.8

Comprehensive emergency obstetric care 0.1 22.8 31.1 24.1

Antenatal corticosteroids for preterm labor 7.3 20.1 17.2 18.5

Kangaroo mother care 20.3 20.6 16.8 19.4

Child (including postneonatal) deaths averted (%)

Use of water connection in the home 3.1 13.4 11.3 12.3

Pneumococcal vaccine 2.9 9.8 7.6 8.7

Pneumonia case management (oralantibiotics)

5.7 19.0 15.9 17.4

Zinc for diarrhea treatment 1.2 5.0 3.9 4.4

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

15/77

14

Fig 1a Trends in maternal mortality in Southeast Asia, 1990-2008(data from WHO Maternal Mortality September 2010)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

16/77

15

Fig. 1b Trends in infant mortality in Southeast Asia, 1990-2008

(Data from Unicef Child Mortality September 2010)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

17/77

16

Fig. 1c Trends in under-five mortality in Southeast Asia, 1990-2008

(Data from Unicef Child Mortality September 2010)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

18/77

17

Fig 2 Neonatal and Postneonatal Mortality Rate Reductions between 1990 and 2008

(Data from IHME, Rajaratnam et al, 2007)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

19/77

18

Fig 3a. Causes of maternal deaths in Southeast Asia (Data from UN MDG Southeast Asia, 2010,

includes 10 ASEAN countries +Timor Leste)

Fig 3b Causes of child deaths in Southeast Asia

(Data from Black et al, 2010)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

20/77

19

Fig 4. Inequities in MNCH intervention coverage in selected SEA countries

Data from Gwatkin et al, 2007; National Statistics Office, www.childinfo.org)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

21/77

20

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

22/77

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

23/77

22

Fig. 5. Trends in maternal mortality and MNCH programs in Thailand, by GDP 1960 - 2008

(Data from Thailand Ministry of Health)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

24/77

23

Fig. 6. Trends in maternal mortality and safe motherhood programs in Indonesia, by GDP 1960 - 2008

(Data from Indonesian Ministry of Health)

Fig. 7. Neonatal Mortality reductions in Thailand (red) and Indonesia (blue) by GDP 1960-2008

(Data from Thailand and Indonesian Ministries of Health)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

25/77

24

Fig 8a. Maternal deaths averted at 60, 90 and 99% coverage of interventions for the ASEAN region(red, orange and purple bars) and regional sub-groups as defined by mortality reduction patterns (blue,

green and yellow bars)

Fig 8b. Neonatal deaths averted at 60, 90 and 99% coverage of interventions for the ASEAN region(red, orange and purple bars) and regional sub-groups as defined by mortality reduction patterns (blue,

green and yellow bars)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

26/77

25

Fig 8 c. Child deaths averted at 60, 90 and 99% coverage of interventions for the ASEAN region (red,orange and purple bars) and regional sub-groups as defined by mortality reduction patterns (blue, green

and yellow bars)

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

27/77

26

Web Table 1 Data sources

DataSource

CountryCoverage Indicators

Estimationmethods Limitations

DHS

Cambodia,Indonesia,Philippines,Vietnam

Time trends for neonatal, infant,under-five mortality, maternalmortality; intervention coverage(vaccination, IMCI, skilled birthattendance, delivery care)

Direct sisterhoodmethod for

maternal mortalityestimates; directmethod forestimation of childmortality rates;estimates ofinterventioncoverage areweightedproportions

Only 4/10countriescovered, time

periods percountry variable;direct sisterhoodmethod mayunderestimatematernal deaths;birth transferencemayunderestimateinfant mortality

MICS

Laos,Myanmar,Thailand,Vietnam

Estimation of infant, under-fivemortality rates; interventioncoverage (vaccination, IMCI, skilledbirth attendance, delivery care)

Indirect estimationof infant and under-five mortality rates;estimates ofinterventioncoverage areweightedproportions

Earlier rounds ofMICS subject toOnly 3/10countries covered

Inter-agencyGroup forChildMortalityEstimation(UNICEF and

WHO)

All 10

countries

Standardized estimation of timetrends in infant, under-fivemortality rates, 1990-2009 for 196

countries

Linear splineregression forcountries withouthigh HIV/AIDSprevalence, Loessregression forcountries with highHIV/AIDSprevalence; weightsapplied for country

data sources

Do not addresspotentialmortality shocksother thanHIV/AIDSepidemic; Loessforecasts ofmortality declinemay beconservative;vital registrationavailable for 5/10Southeast Asia

countries

IHME:Rajaratnamet al.

All 10countries

Standardized estimation of timetrends in neonatal, infant, under-five mortality rates for 187countries from 1970-2009countries

Gaussian processregression ofunder-five mortalityaccounting for non-sampling error;infant and neonatalmortality modeledfrom under-fivemortality usingmultilevelregression

Yields lowerestimates ofmortality thanother methods;similar modelingapproach forcountries withand without highHIV prevalence;vital registrationavailable for 5/10Southeast Asiancountries

MaternalMortalityEstimationInter-AgencyGroup(WHO)

All 10countries

Standardized estimation of timetrends in maternal mortality ration1990-2008 for 172 countries

Direct estimation

from civilregistrationsources; multilevelregression modelfor other types ofdata sources

Underreporting/misclassification of

maternal deathsin householdsurvey sources;did not includesubnational datasources

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

28/77

27

IHME: Hoganet al.

All 10countries

Standardized estimation of timetrends in maternal mortality ratiofor 181 countries, 1980-2008

Two-step spatio-temporal regression

Underreporting/misclassification ofmaternal deathsin householdsurvey sources;idid not extractincidentalpregnancy-

related deaths;mpact of HIVepidemicmodeled directly;vital registrationavailable for 5/10Southeast Asiancountries;Myanmar andVietnam nonational dataavailable

CHERG:All 10countries

Cause of death estimation forneonatal, infant, under-fives

Direct estimationwith ICD-10 codesfor complete vitalregistration data;

for countrieswithout completevital registration,separate multicausemultinomialregression modelsfor countries withlow and high childmortality usingverbal autopsysources; separationestimation ofneonatal tetanus,malaria, measles,pertussis, HIV/AIDS

Highest mortalitycountries ofSoutheast Asia donot have vitalregistration,estimates aremodeled

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

29/77

28

Web Table 2 Effect sizes LiST

References: Institute for International Programs. LiST: The Lives Saved ToolAn evidence-based tool for estimatingintervention impact. http://www.jhsph.edu/dept/ih/IIP/list/index.html; Plosky WD, Stover J, and Winfrey B. The Lives Saved Tool

, A Computer Program for Making Child and Maternal Survival Projections. December 2009.

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

30/77

29

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

31/77

30

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

32/77

31

Web Fig. 1 Mortality Reductions with GNI per capitaMortality data from UN MDG Reports September 2010; GNI per capita from World Bank

Fig 1a Scatterplot of maternal mortality against GNI per capita in 1990 and 2008

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

33/77

32

Fig 1b Scatterplot of infant mortality against GNI per capita in 1990 and 2008

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

34/77

33

Fig 1c Scatterplot of under-five mortality against GNI per capita in 1990 and 2008

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

35/77

Reviewer #2:

OVERALL

This paper has improved considerably since the last review in July. The big picture is

clearer and the authors have made considerable efforts to respond including to specificissues such as which countries are included. The shift from MCH to MNCH is

appropriate especially in this region given the epidemiology. The trend analysis formaternal is improved and they have added a MMR/GNI plot although this is hard to

interpret easily.. The LiST analysis adds novel data inputs, although is not clear which

interventions are included and seems primarily maternal focused plus some neonatal andapparently no child. The program priorities are clearly stated for maternal (unsafe

abortion, PPH and HDP) but are not at all clear for child and neonatal. Generally the

paper remains much clearer for the maternal but is still weak for neonatal and child. It

still requires more work to be a Lancet level paper with clear inputs, discussion of thelimitations and yet clearer outputs especially for the child/neonatal parts.

1. Data used and sources cited

Table 1 makes the data sources much clearer, although the column on estimation methods

is so non-specific it does not add much and several cells are empty. This column could bedeleted or else needs more detail to be of standard for Lancet.

More information on estimation methods and on limitations has been added to Table 1which has now been moved to the Web Appendix

There is still some confusion in the text regarding sources especially of estimates forcause of child and neonatal deaths. These estimates are referred to as CHERG (note is

Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group nor research group), Lancet paper by Black

and colleagues, Countdown, and WHO. They are all the same. CHERG does theestimates with WHO, they were published by Black et al and then Countdown uses these

estimates as do all of UN system.

We have included the published source, reference 11, rather than the original source for

easier tracking on the part of the ordinary Lancet reader

Some remaining issues with the data

a. Under five or infant mortality or neonatal? Given the MDG 4 target and the epithe appropriate measure are under five mortality and neonatal mortality. Infant mortality

just parallels under five and the neonatal diffrs, links more to maternal and requires

differing policy/program solutions and so is the outcome being tracked with under five byCountdown and most data for action movements. Fig 1 has under five and infant. Fig 3

has neonatal and postneonatal mortality. Postneonatal is only to one year of age and

ply to Reviewers Comments

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

36/77

MDG 4 is for under five mortality. Is this really postneonatal just up to infant or is it

under five? There are several times throughout the paper where the outcome of interest isnot clear especially in the child health sections.

We have clarified our definitions for neonatal, postneonatal and child mortality in the text

of the methods section on p 2 and made distinctions when writing about these differentoutcomes in the relevant sections on pages 3-4.

b. Neonatal percentage of under five deaths: The table states that the data source

for child and neonatal deaths is Black et al Lancet (CHERG/WHO) but gives the neonatal

as "more than a quarter of child mortality" (page 4) and 26/7% in fig 4b. The SEAcountries included in this paper are from WHO regions WPRO and SEARO but these

regions have neonatal as 54% or 52% of under five deaths. Where does the data in fig 4c

come from? Seems implausible to me although I have not added up the specific countries.

I wonder if the authors have taken the neonatal % of infant instead of under five? Orsome other explaination? This neonatal % of under five would be lower than Africa

which has malaria and HIV in the postnatal and child proportion which pushed down theneonatal %. Does not seem at all likely that SEA has a lower neonatal % of under fivedeaths than Africa. Important to check this data carefully.

The ASEAN countries are split between WPRO and SEARO, and one reason for singlingout this region is to assess its performance outside the influence of larger states like India

(which dominates SEARO) and China (which does likewise in WPRO). We have re-

checked our data for Fig 4b (now renamed Fig 3b) and re-made the figure, which isdiscussed in the third full paragraph on p 4.

c. Causes of death in the neonatal period: Neonatal is a time period not a cause

and so should not be left as a slice in the pie - the UN estimates give the specific causesin the neonatal period and if this paper is to move the agenda forward then these causes

should be listed and some actual interventions mentioned somewhere in the paper.

Fig 4b is renamed Fig 3b and now includes the neonatal causes of mortality

2. LiST analysis

This analysis adds novel data inputs. However the input and methods for LiST are not at

all clear.

The LiST methods discussion has been revised to add more detail beginning in the lastparagraph on p 2.

a. Interventions: it is not clear which interventions are included apart from BmoC

and CEmOC (table 3). The BEmOC seems to save more maternal lives than the CEmoC

which is surprising. Might this have been transposed? The LiST analysis seems primarilymaternal focused with none of the specific neonatal high impact interventions after

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

37/77

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

38/77

Additional analysis has been made and presented for the case studies. We discuss

analytical methods and data used in more detail in the methods section on p 2 and haveextended the rationale and discussion on p5.

Then the text box is also on MMR reduction but is Malaysia - for a paper on MNCH it

seems that having 2 case studies on MMR reduction is not very balanced. What aboutchild, and/or TFR and/or adolescents? Also note some of the text in the text box is

missing.

We have not addressed this comment as we believe it was referring to a previous draft of

the manuscript.

The Indonesia fig (8) is a nice eg but is not very analytical and may be hard to follow for

those not familiar with Indonesia. Both examples are wholly maternal which does not fitwith the title of MNCH and the global shift to a linked MNCH agenda.

This portion has been re-written on p 5 and a graph and discussion on neonatal mortalityreduction in Indonesia and Thailand added, fig 7.

Messages from the data to inform policy and programme action

There is some synthesis of the data trends - eg high inequity, increasing % of U5M that is

neonatal, high prevalence of underweight children, yet rapid progress in almost all SEAcountries (fig 1) etc. Hiwever there is still very limited focus on what this means for

programmes - if high inequity is a major issue what can policy makers do? Targeting?

Other strategies? Seems little point in describing them and not acting. The Brazil successfor reducing disparities in mortality, under five stunting etc as per the Victora et alanalysis in WHO Bulletin may give useful insights. Major trends in the region such as

urbanization and models of care to reach the urban poor are not covered. Also as this

series is in Lancet not a national or regional journal then other countries will be interestedin lessons learned that may apply to other regions, and this remains weak.

Some suggestions have been for policy and program action, although the aim is really forstronger solidarity within the ASEAN region for MNCH rather than to point out specific

actions.

In summary, this paper is much stronger than it was but still does reach the standardsexpected for a Lancet paper. The data inputs especially for child and neonatal have some

technical questions outstanding. The LiST analysis is a useful addition but requires moredescription, discussion of limitations and application. There is limited critical analysis of

differences between countries so reads more like a UN piece than a Lancet paper. Why

have some countries progressed? If some are tailing off why is this? The implications andactions are not very clear for policy/accountability. The gaps are more notable for

child/neonatal nutrition than for maternal.

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

39/77

Reviewer #3:

The revised version of the manuscript is improved over the past document. However,there are still many important issues that need to be addressed. The issue of the selection

of the countries as a viable or actual organization or institution still needs to be clarified

or explained better.Other commeents will be in the dicussions below.

1. There is an improved attempt to defend the choice of the ASEAN countries as the

focus for the study. The rationale to use this geographic grouping as countries needs to be

clear and improved upon, as the issue of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and even China

are important as well. It is just that most regional analyses usually look at Asia as abigger area and involve not only these countries in the paper, but also India, Pakistan,

Bangladesh, and China. Why ASEAN? Why choose this aggrupation of countries?

Would there be something special in this that would facilitate or enhance progresstowards meeting the MDGs? Although the reply to the request to clarify the selection of

this region or group of countries was mentioned, the reply was not convincing and clear

enough.

We included additional justifications for ASEAN on p 1, but also refer the reviewer to

the Overview paper for this series on why this group of countries has been selected

Virasakdi C, KH Phua, MT Yap, NS Pocock, J Hashim, R Chhem, SA Wilopo and AD Lopez, Health in

Southeast Asia: Diversity and Transitions, Lancet (overview paper, accepted for publication)

2. In the first paragraph of the Introduction, may I suggest changing "plateauing" to

"leveling off"?. Plateau gives an indication of an flattened surface that is elevated, when

the intent of the authors seem to suggest a levelling off at a declining surface.

We changed the word "plateauing", as recommended on p 1

3. Some of the citations, such as the reference for the WHO mortality estimates havebeen published since and may need to be updated.

We used the most recent reports from WHO and UNICEF, September 2010 as our keyreferences, reference numbers 2 and 3.

4. The statement of the objectives in the last part of the introduction is not very clear.

There also is not enough discussion on the significance of this paper, other than thoseissues that are already known to these countries. As suggested by the past reviews, there

is still a lack of novelty in the paper, as the information presented would have been

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

40/77

known already to the supposed target audience. What is new to this paper, and what is the

important message that needs to be mentioned with regards to the findings?

We have highlighted the following key messages: major disparities, significant success

stories, general progress on child health, more to be done on maternal and neonatal

health, we provide recommendations on major interventions of which to expand coverageand recommend integrated, coordinated approaches within the health system to increase

coverage. We have strengthened the rationale for the paper on p 1 of the introduction.We note in the methods section on p 2 that this type of LiST analysis undertaken in the

paper has not been done for this region previously.

5. Since a lot of acronyms are mentioned, it may be helpful to spell out some of these in

the first instance they appear in the paper, or in a glossary somewhere.

We have spelled out any acronyms when first mentioned in the paper.

6. While the authors attempted to use many sources of information, there areinconsistencies between the methodologies, sampling, analysis and results of these

various sources that the issue of comparability and using them for trends analysis may be

brought up. There may be a need to expand the limitations column in the table of the datasources to give a deeper analytical view on these methodological variations that affects

the data. It can be stated that the variations may be present, yet may triangulate each otherto a certain pattern or trend.

The Table on data sources has been expanded and moved to the Web Appendix as table

1. Limitations of the data sources are discussed beginning on p 8.

7. I am not sure if a reorganization of the paper to focus first on the rates and trends of aparticular statistic, then its causes and factors, effects of interventions, and possiblerecommendations may be a better way. There still seems to be a lack of flow from one

topic to the next. Regrouping the data together thematically may improve this flow.

We considered the reviewers suggestion but were concerned that it would require

extensive reworking of text. We have attempted to improve the links between the

different parts of the results and discussion and hope this addresses the reviewer'sconcern

8. The case studies of Thailand and Indonesia focused only on maternal mortality

reduction when the whole paper intends to address also newborn and child mortality.

A graph, fig 7and discussion on neonatal reduction for Thailand and Indonesia has beenadded on p 6, first paragraph. We have also clarified the rationale for these case studies

on p 5 at the beginning of the case study section in that we are not focusing specifically

on maternal mortality reductions per se, but seeking to understand what factors account

for Thailands more rapid pace of mortality reduction. The statistical model underlyingfigs 5 and 6 has been added in the methods section on p2 to clarify this.

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

41/77

9. On page 6, on the issue of Lives Saved (which is not a good heading for a section by

the way), aside from the numbers in the table, there seems to be no further explanation orevidence on the effect of providing comprehensive care in certain subgroups. This

analysis seems superficial or shallow, and may need to be further explained if the target

audience of the paper are policy makers and programme planners.

This portion has been re-written and the heading revised on p6. The discussion of the

LiST for this paper is not intended to point out specific interventions to implement, butrather to illustrate the effect of contextual differences between and among the sub-groups

on deaths averted, keeping coverage constant. This approach was taken so that

policymakers may appreciate the interaction between coverage and the health system andsub-group context in setting expectations about the extent to which mortality can be

reduced.

10. ASEAN is a political aggrupation of countries nearby each other within ageographically defined region. But aside from this, how much is Health in their agenda?

Is there some coordinating mechanism to support any health measures? Have there beenany past health issue that has been raised in ASEAN and has been addressed properly? Isthere a way to include some description of the "health track record" of ASEAN?

This concern has been addressed at the end of the paper on p 8.

11. Table 1 would probably need some reference citation or superscript citation. As

mentioned previously, the limitations column should be expanded to give a more criticaldescription of the use of the data.

Table 1 has been moved to the Web Appendix and expanded as suggested

12. Why is Table 2 being presented? The table shows that there are differences betweensources of information. This was not properly discussed in this paper, nor is a reference

to this dicussion possibly in other sources is not found. The title denotes a comparison,

yet there is no actual comparing in the paper.

Table 2 has been deleted as not contributing substantially to the key messages of the

paper.

13. Table 3 shows the subgroups in terms of levels of obstetric care. Are these subgroups

referring to what? Are these the countries mentioned previously? Also the total in the last

column under ASEAN does not add up from the previous columns. Where did thisnumber come from? Is there a reference for this table, as it looks adapted from another

source. If it is an originally produced table, the methodology in getting that information

would b needed.

Table 3 is now Table 1 and has been revised. This is an originally produced table and themethods section has been re-written to reflect this

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

42/77

14. Figure 1a, 1b and 1c seem to be copied and pasted. They are not very clear.

Fig 1 a, b and c have been revised; Brunei and Singapore (which are high income

countries) were removed for better clarity

15. Figure 2 states at the bottom that the plots for IMR and U5MR are similar to MMR: Ifsuch is the case for the pattern in putting figures, it would not be proper not to put the

other figures, as people may want to use this paper as a reference for information, if itgets published.

Fig 2 has been renmaed Fig 1a, b and c for the Web Appendix and includes the IMR and

U5MR plots against GNI per capita

16. Figure 3 is vague. What is the value of providing the ifnromation on rate reduction of

neonatal and post neonatal mortality, without a proper discussion. And why is such a

table presented when the rate of maternal mortality reduction may also be important,

being oneof the main objectives of this paper.

Fig 3 has been renamed Fig 2 and its related discussion improved on p3. We use fig 3 to

show that reductions in neonatal mortality have not been consistent across countries ofthe region, nor have they kept pace with postneonatal mortality reductions. This then

links to the LiST analysis on the need to expand coverage of targeted neonatal mortality

interventions. The rate of maternal reduction has been extensively written about inrelation to Fig 1a and the case studies. We made a graph on the rate of maternal reduction

in response to this comment, but we find that it does not provide anything additional to

the paper so we have decided not to present it.

17. Figure 5. The information of underweight children seems to be out of place, as mostof the paper is discussing mortality.

This Fig and the corresponding discussion on underweight has been deleted

18. Figure 6. The bar diagrams continue to be small, and the information provided is

vague and not useful. It may be helpful if the authors insist on including these figures to

explain each trend or finding separately, and to describe the changes within in eachcountry and across countries more clearly.

Fig 6 has been renamed Fig 4 and enlarged. Additional explanations re: this figure have

been made in section beginning on p 4

19. Figure 7 and 8 would need references.

Fig 7 and 8 have been renamed Fig 5 and 6; references have been included in the text andthe figures

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

43/77

20. Figure 9 and 10 would need references, and some clarification if the subgroups

mentioned here are the same as in other parts of the paper.

Fig 9 and 10 have been renamed Fig 8 a, b and c (a graph on interventions to reduce

child mortality has been added to address another reviewer's comment) and these figures

come from primary data so references are not needed; clarification regarding the sub-groups has been added to the text on p6

21. In the last page of the main body of text, there is a statement on "ASEAN neighbors

may support each other in the spirit of South to South cooperation, ......". What do the

authors exactly mean by this recommendation, which reads like a motherhood statment,without clarifying specific programmatic implications.

This statement has been deleted and this paragraph re-written

Reviewer #4:

A very interesting investigation, though at the moment the figures really let the

manuscript down.

1. Due to the different patterns of the countries some countries are almost

impossible to see on the Figures because they were already low on 1990 and therefore are

hidden from view.

Figures 1 a, b and c have been revised, removing Brunei and Singapore (which are

considered high income countries) for clarity

2. The x-axis on Figure 1b is not ideal. Time should be evenly spaced.

This has been addressed in the revised graphs

3. The percentages expressed and the details in table 1 are not clear. The total does

not seem to be the sum of the constituent parts.

The table with the LiST interventions being referred to has been revised

4. The graph in Figure 2 is poorly showing the data as most of the points are tooclose to the point of origin, and the two different time points are not easily

distinguishable.

Fig 2 has been renamed Fig 1 in the Web Appendix and has been revised for better

clarity; Brunei and Singapore have been removed from this Figure as well

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

44/77

5. What are the additional lines on Figure 8, they obscure the text.

The revised Fig 8 is now Fig 6 and these extraneous lines have been deleted

6. The authors have not really discussed the differences between the surveys; these

are fundamental differences, though the patterns over time are more similar. This leads toa wider point that the limitations of the data sources are not really fully detailed. The

discussion does not go into the limitations in the required depth at all.

Additional explanations including details of data sources have been added in the methodssection to address this, including extension of what is now webtable 1. A section on

limitations of the study has been added in the discussion beginning on p8.

7. On a related point the impact of the health changes is not really discussed in

enough detail to understand whether the changes mentioned will really have the impact as

the data with the estimate of the impact is not provided and the limitations not discussed

at all.

We are not sure whether the reviewer is referring to the case studies with this comment or

to the LiST results - improvements have been in the discussion of both these sectionswhich we hope addresses this concern. Limitations of data sources and analysis have

been added to the discussion section on p 8.

8. A LiST analysis does not easily have a confidence interval in the normal sense

of the word, but it is usual to discuss scenarios for providing some form of a range on the

estimates provided. This is a separate issue to the coverage ranges which have the sameerror.

LiST is based on point estimates and currently does not have the ability to provideuncertainty bounds in a meaningful way. One could do individual countries and then domedian effect sizes and range / 95% CI but would not be appropriate given that we arenow presenting pooled results and regional bands. The number of countries in eachgroup is also small. So the simpler approach is to restrict the model to estimates atvarying levels of coverage and see where the gains are.

-

8/6/2019 THELANCET-D-10-04958 (1)

45/77

1

Title: Maternal, neonatal and child health: Now (more than ever) for Southeast Asia

Order of Authors: Cecilia S Acuin; Geok Lin Khor; Tippawan Liabsuetrakul; Endang L Achadi; Thein

Thein Htay; Rebecca Firestone; Zulfiqar A Bhutta,

Key messages