Synopsis, CFB No. 15

Transcript of Synopsis, CFB No. 15

Brussels StudiesLa revue scientifique pour les recherches sur Bruxelles/ Het wetenschappelijk tijdschrift voor onderzoek overBrussel / The Journal of Research on Brussels Notes de synthèse | 2009

Social inequalitiesSynopsis, CFB No. 15Sociale ongelijkhedenInégalités sociales

Christian Kesteloot and Maarten LoopmansTranslator: Mike Bramley

Electronic versionURL: http://journals.openedition.org/brussels/1009DOI: 10.4000/brussels.1009ISSN: 2031-0293

PublisherUniversité Saint-Louis Bruxelles

Electronic referenceChristian Kesteloot and Maarten Loopmans, « Social inequalities », Brussels Studies [Online], Synopses,Online since 03 March 2009, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/brussels/1009 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/brussels.1009

Licence CC BY

Synopsis nr. 15

Social inequalities

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans

Translation: Mike Bramley

•Christian Kesteloot is a Professor in the Institute for Social and Economic Geog-

raphy at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and part-time lecturer at the Université

libre de Bruxelles.

Contact: Contact : [email protected] - ++0032 (0)1/632.24.32

• Maarten Loopmans has a PhD in Geography and lectures on the STeR*-

Stedenbouw en Ruimtelijke Planning course at Erasmus University College Brussels.

Contact: Contact : [email protected]

the e-journal for academic research on Brussels

www.brusselsstudies.be

Contact Brussels Studies : M. Hubert (dir.) – [email protected] – ++ 32 (0)485/41.67.64 – ++ 32 (0)2/211.78.53

www.citizensforumofbrussels.be

Brussels Studies is published thanks to the support of the ISRIB (Institute for theencouragement of Scientific Research and Innovation of Brussels - Brussels-Capital Region)

Conference-debate:

9 March, 19.45

Centre culturel

Jacques Frank

Chée. de Waterloo,

94

1060 Brussels

I. Observations

1. Economic and cultural globalisation

The Brussels Capital Region has experienced a significant period of economic

growth over the past few decades. The service sector has been particularly respon-

sible for this economic performance, largely comprising the European, federal and

regional administrations. However, overseas investments in the service sector have

also been an important factor. In broad terms, Brussels has 2000 foreign compa-

nies, which account for 234,000 jobs and 40% of the Brussels GDP. Over the past

few years, people in the Halle-Vilvoorde and Nijvel arrondissements have benefitted

more from the Brussels-effect than those actually in Brussels. The economic growth

in Brussels between 1995 and 2005 measured 2.2% (higher than in both Flanders

and Wallonia); in Vilvoorde it was 2.9% and in Nijvel it even reached 4%.

This economic success can also be seen in a population growth that stems from

immigration, making Brussels the most global city in Belgium, in terms of its popula-

tion. Around 30% of the population have a different nationality than the Belgian na-

tionality (and a further 20% of Brussels residents have swapped their original nation-

ality for the Belgian nationality). Just as in the majority of cities in Flanders, Brussels

immigration is a relatively recent phenomenon and the foreign population has grown

strongly since the 1960s. The foreigners in Brussels are mainly the result of various

waves of post-war immigration. It is estimated that there are currently around 170

nationalities within the Brussels area.

Each expansion of the EU sees highly-skilled people from the new countries arriving

to join the ranks of EU officials and bringing a whole community in their wake. The

larger Europe becomes, the greater the attraction of the city is for important eco-

nomic actors, whether leaders and executives of multinational companies, or spe-

cialised services for companies that operate in the world economy and are based in

Brussels in order to manage their European activities.

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

1

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

The other side of the social spectrum used to be dominated by the migrant workers

of the 1960s and 1970s, who in turn replaced low-skilled Belgian workers. Many of

these migrants have not had the chance to help their children climb the social lad-

der, as the crisis of the second half of the 1970s and the 1980s prevented them

from doing so. However, since the 1990s they have been joined by a new wave of

migrants who this time come from all over the world and who stay here illegally,

temporarily or permanently and who often seek an income through informal activi-

ties. They often end up in activity sectors where common strategies for keeping

prices low, such as mechanisation or delocalisation to low-wage countries are not

possible and where the solution is found in the search for informal and low-paid

labour (e.g. in the construction, catering, cleaning and transport sectors, etc). These

sectors also experienced a boom through the growth of the Brussels economy (for

instance, in the construction and maintenance of offices, the growth of the catering

sector through the increase in tourism and wealthy knowledge workers, etc).

2. Polarisation or open society?

a. Socio-economic change: polarisation between high and low income groups?

Despite the large welfare production and international attractiveness of Brussels, the

city has also experienced serious socio-economic problems. The unemployment

level, which has hovered around the 20% mark over the past few years, is extremely

high. The average family income decreased from 160% of the national average in

1963 to only 85% in 2005. Such changes conceal distinct internal contrasts. While

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

2

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

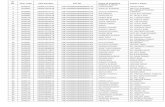

decile 1

decile 2

decile 3

decile 4

decile 5

decile 6

decile 7

decile 8

decile 9

decile 10

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

198519861987198819891990199119921993199419951996199719981999200020012002200320042005

The growing income gap in the Brussels Capital Region 1985 – 2005

ind

ex

one in four residents of Brussels lives under the poverty line, Brussels is also home

to a growing, well-paid transnational elite estimated to account for between 10%

and 15% of the population. The gap between these different income groups is

growing and the absolute purchasing power of the poorest is decreasing. This is

shown in the graph below, which indicates the division of the taxable incomes in

constant prices per decile.

There is a growing disparity between the highest and the lowest incomes since the

end of the 1980s. The gap remained stable during the better economic spell be-

tween 1988 and 1991, but continued to grow again from 1992 onwards (due to

changes in the tax law, there are gaps in the series so new index years have had to

be taken). The purchasing power of the lowest 10% decreased at the end of the

1980s and has continued to do so since 1992. Tax fraud and the informal economy

are perhaps the most important factors in creating the disparity between the figures

and the actual situation; however the historical trends that the graph shows are

nevertheless alarming.

b. Socio-spatial inequalities on different scale levels

The internal socio-spatial polarisation in the Brussels city region is greater than

elsewhere in Belgium: the Brussels city region has the municipality with the lowest

average taxable income per tax return (Sint-Joost-ten-Node) and the municipality

that was the richest for sev-

eral years and still now ranks

amongst the richest (Lasne).

In 1993, the average taxable

income per taxpayer for Sint-

Joost was only 48,4% that of

Lasne. In 2005, it dropped to

42.6%. The difference be-

tween these two municipali-

ties, one in the city centre, the

other in the periphery, is not

just coincidental. Urban

growth has mainly taken

place in the suburban belt

over the past 50 years and

has been socially selective.

The new houses in the pe-

riphery (largely outside the

Brussels Capital Region) were

erected for the middle and

higher classes, enabling them

to leave the city centre. The

lower income groups were left

behind in the city centre. To a

large extent, the various im-

migration waves also followed

this pattern: rich immigrants

settled in the periphery, mainly

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

3

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

EVOLUTION OF TOTAL TAXABLE INCOME 1976 - 20051976 = 100 Constant prices of 2004

in the east; poorer migrants ended up in the westerly working-class districts, the

‘poor crescent’ of Brussels.

The spatial distribution of the total taxable income per municipality in the city region

shows the result of this process. Due to the selective character of suburbanisation,

the population decrease and the economic crisis, the global incomes of the total

population in the central municipalities of the Brussels Capital Region have almost

seen no increase over the past 30 years, whilst the municipalities in the periphery of

the city region (mainly in the south-east) have been able to triple this wealth (the

policy consequences of this will be examined further on).

This pattern has recently been disturbed by gentrification. New types of households,

often young double-earners or young transnational knowledge workers, choose to

settle in centrally-located neighbourhoods with attractive housing and an attractive

public area. In certain neighbourhoods, this has led to a new social mix, whilst in

others this has increased the elitist character of the neighbourhood. In all cases,

gentrification and the population growth of the Region compound the price in-

creases on the housing market and in the local retail outlets, making it increasingly

difficult for the lowest income groups to find decent housing, which results in slum-

lords and homelessness.

The existing segregation also mirrors the spatially differentiated access to the em-

ployment market. The Brussels economy is strongly dependent on the contribution

of mainly highly-skilled external workers from Flanders (230,000 in 2006) and Wallo-

nia (126,000). The Brussels residents often do not possess the required qualifica-

tions and command of languages for the jobs that Brussels and the surrounding

area create as a capital city and European centre (98% of unemployed people in

Brussels are monolingual – mostly French-speaking – and for that reason alone,

they are refused jobs in the city’s demanding international economy or in the sur-

rounding Dutch-speaking areas). A job in the periphery is also often very difficult to

reach from the city centre using public transport.

The jobs that remain offer disproportionate prospects on insecure and low incomes.

Temporary work increased by almost 200% in the Brussels Capital Region from

4.3% of paid work in 1992 to 12.6% in 2006, whilst this share only increased by

77% for the country over the same period. Temporary work is highly sensitive to

economic fluctuations and therefore offers little security of income.

c. Multicultural Brussels: inclusion or conflict?

The fast diversification of the Brussels population altered the character of the city

considerably. The foreign population in Brussels comes from all over and comprises

((grand) children of) earlier guest workers, Euro officials, multinational expats, refu-

gees and illegal immigrants; some of whom are extremely rich and some extremely

poor. This diversity leads to problems and conflicts including mutual racism and

discrimination, riots and other expressions of abhorrence towards “the other”; origin

and colour also seem to have a significant influence on the opportunities for climb-

ing the social ladder.

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

4

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

The inclusion of all these different groups in a common urban project is no simple

challenge for the future. The one-sided vision on the ‘integration’ of guest workers in

and by a Belgian francophone middle-class-determined society from the 1970s to

the 1990s is no longer appropriate. Brussels is evolving towards a multifaceted di-

versity where adjusting to the multicultural reality is becoming a more realistic per-

spective than adapting to a monocultural host city. At the same time, the noncom-

mittal way in which integration is being dealt with in Brussels is also dangerous.

Having no duty to integrate is actually the same as not having compulsory education

in the sense that the weakest groups are deprived of chances to work their way up

in society. Furthermore, there is also the threat of the spectre of communitarisation:

in all this diversity, how do you maintain a shared ‘imagined community’ that makes

mutual solidarity possible and prevents groups from voluntarily shutting themselves

off from repression or calling for repression against others?

d. Towards a repressive welfare state?

After the Second World War, Belgium developed an extensive welfare state with a

social security system that, up to the end of the 1970s, had the ambition of eradi-

cating poverty in society. Today, this ambition is needed more than ever as Brussels

has so far not succeeded in guaranteeing decent housing for everyone. The pres-

sure on the housing market mainly affects the lower realms of society and requires

large-scale investments in the social rented sector; however, social housing policy

continues to lag behind.

Brussels education policy is also no longer able to create more social equality. Both

Flemish and French-speaking education score very badly in international compari-

sons when it comes to offering equal opportunities (PISA comparison) and therefore

form an important factor in reproducing inequalities in Brussels society. This is dam-

aging for the future, especially in an immigration city such as Brussels, where thou-

sands of young newcomers arrive each year requiring extra efforts to be made.

Where the efforts in Brussels for combating social inequalities are thin on the

ground, it seems that investments in repressing weaker groups increase. The home-

less in the consumer-based city centre are deported to Neder-over-Heembeek and

illegal immigrants are not even safe from the Department of Federal Immigration on

public transport. The seemingly legitimate demand for public order from prosperous

groups that are returning to the city centre is increasingly being aimed at the pres-

ence and the objectionable behaviour of certain groups (allochtonous youngsters,

the homeless and street prostitutes).

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

5

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

II. Questions-issues

1. Which policy?

The main problem therefore consists in significantly decreasing the social inequali-

ties to a level where each inhabitant of the city has the guarantee of being able to

live in a decent way. This is a question of social justice that the city should be able to

guarantee to all its inhabitants, in the first instance comprising decent affordable

housing, access to an income that provides decent food, clothing and household

goods (or direct access to these means of existence), access to decent healthcare,

education, culture and mobility.

a. Integration through the market?

These living conditions are primarily assured in our capitalistic society through ac-

cess to the employment market and remuneration for the work done that is high

enough to provide the required income security. However, even in one of the most

competitive regions of the world economy, the employment market offers no guar-

antee for improving the fate of the poorest population, nor does it guarantee quick

integration and the upward social mobility of newcomers to the urban Community.

b. Integration through reciprocity?

Other paths do exist for combatting social inequality. Direct mutual solidarity and

reciprocal help between people via social networks is a matter of life and death for

some in our society. In order to make this reciprocity possible, people try to live in

the vicinity of their family and ethnic groups remain living together. It is no coinci-

dence that this has been the reason why all sorts of initiatives have also focussed on

the structure of society and social cohesion. However, social networks do not bring

universal happiness. Mutual solidarity is conditional and limited to members of the

network; people who are in need of solidarity within their network do not always

have much room for negotiation in exacting this solidarity. Furthermore, social net-

works are often intrinsically linked with identitarian processes which often make

them socially selective, which in turn excludes the weakest groups from the strong-

est networks.

c. Integration thanks to the government?

The government’s redistribution policy, particularly in the construction of the welfare

state in the previous century, is a more extensive alternative. By levying taxes and

collecting social security contributions, the government centralises part of the pro-

duced wealth and distributes it once again according to politically-determined rules.

The most important instruments in this are the (increasingly less) progressive tax

rates, the social security that provides supplementary or substitute incomes and

access in kind (mainly for healthcare, but also for housing in some countries) on the

basis of the collected contributions from employees and employers and/or taxes.

The government is also able to act in a regulatory way on the employment market in

an attempt to steer the division of incomes at the source: possible ways include

monitoring discrimination, stimulating jobs for groups that have little chance on the

market (e.g. the low-skilled), but also regulating working time, the level of the wages

and working conditions. Finally, the government also takes care of a number of col-

lective consumer goods and services: information, communication and transport

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

6

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

resources, trade, schooling and training, culture, recreational infrastructure, safety

and healthcare.

2. On which levels?

The government’s redistribution task is organised on different levels. The debate

about which task is best handled at which level is both complex and age-old, and is

also often embroiled in communautaire issues in Belgium. The question here is

which role the Brussels governments can play in this jumble.

The regulation of the employment market is under much pressure: cities and nation-

states are played off against each other as competitors and are left with little room

to put forward social needs in employment market policies. Another way could be to

extend the European level, because this level still transcends the logic of competi-

tion to some extent, but pressure from below is needed for this; from the city, where

the tension between competition and solidarity is the most tangible. In order to

make Brussels more social, it needs to join together with other cities in unambigu-

ously pleading for a more social Europe. The same issues arise on the level of social

security, which has historically been developed on the level of the national state.

Regions (not only Flanders) are demanding to have more of an impact on social

security so that redistribution flows can be directed into their own competition strat-

egy. With a low employment level of city inhabitants, a large number of commuters

and high levels of unemployment, this is not a beneficial path for Brussels to take.

Should Brussels not rather plead for this redistribution system to be raised to the

European level, making it a core element of social Europe?

The city is traditionally the locus of collective consumption. However, Brussels is

confronted here with a double field of tension. The city’s care hinterland extends

beyond the Region’s administrative borders, roughly corresponding to the regional

employment basin. However, because the financing of this service is largely done

through the Region and the Brussels municipalities, many users (the commuters)

contribute less to its financing. External financing (which is not exclusively borne by

the commuters) is only for ‘personal matters’ (from the communities) and from spe-

cific funds such as Beliris or the Grootstedenbeleid (from the federal government).

On the other hand, tension surrounds internal redistribution: which Brussels resi-

dents benefit from collective consumption? The problem of the Brussels municipali-

ties arises here. There are 19th century working-class districts from the first belt as

well as more prosperous districts from the second belt in the majority of the munici-

palities; there are social housing estates and private residential neighbourhoods. It

should be evident that the necessary solidarity is developed on this level and that

the municipal policy relating to collective consumption therefore works in a redis-

tributive manner. The problem is more that municipalities have good reasons for

taking other paths than that of solidarity. The Brussels municipalities are competitors

in fiscal terms and use housing policy and spatial planning to pass on the poorest

inhabitants to one another and to attract the richer inhabitants (a sort of spatial

Blame Game). By attracting people with high-end jobs and elbowing out people

with low-end jobs, an attempt is also being made to increase the value of property.

This enables the municipalities to increase their incomes from the supplementary

taxes on the income tax and also on the property tax. In this context, urban renewal

is usually an operation that provides benefits on both levels. Gentrification in one’s

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

7

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

own territory is a desirable evolution, whilst the addition of new social housing is

avoided like the plague. The question is therefore one of how the fiscal competition

between municipalities can be changed into distributive justice. This would involve

poorer municipalities receiving more resources, and also that these resources are

actually used in tackling the inequality and not for improving their competitive posi-

tion.

The municipalities, the Region, the Brussels hinterland, Belgium and Europe are all

involved in the battle against social inequality in the city. It all boils down to allowing

these different levels to work together and to prevent competition emerging within

and between these different levels.

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

8

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

III. Policy options

1. Institutional changes as politics of scale for the poor?

As the production of wealth is extensive enough in Brussels, the question is one of

how this wealth can be fairly distributed across the population. This redistribution

can not be viewed in isolation from the institutional structure of the Belgian state. So

what are the institutional paths that can now be taken for achieving fairer redistribu-

tion?

a. Increasing the size of the region?

The call for increasing the city region is great as this would mean that the expense

of collective consumption could also be carried by the broad shoulders in the pe-

riphery. The realisation of an institutional city region is not simple and is a source of

political ideological conflicts. This is increasingly hampered in a Belgian context due

to the communautarian issues. However, the most important question is whether

this will counteract socio-economic polarisation. Even if the resources available to

Brussels were to increase, then there is still no guarantee that these increased re-

sources would actually be used to close the social gap in Brussels. An expansion of

the city region would also primarily involve an extension of the political power that

the rich suburban citizens have over the centre. In terms of spatial planning, mobility,

trade and investments, political parties that are also popular within the rich periphery

of Brussels, have so far utilised the Brussels resources more in favour of the city

users than those who actually live there. Instead of using redistribution, socio-

economic tensions are mainly combatted through repression.

This does not do away with the fact that it is essential to hold the city users partly

responsible for the city’s future; firstly by obliging them to contribute to the costs of

the collective consumption that they benefit from in the city and to compensate

them with a vote in the matters that concern them in the city. In a more structural

way, the integration of city users within the urban community demands umbrella

institutions within which people can negotiate with each other about the future of

the city, from three structural interest positions: the poor and the newcomers who

live in the central area of the city, the Brussels middle-class who reside in the better

(parts of) the Brussels municipalities and the city users.

b. Making the municipalities smaller?

An alternative to the expansion of Brussels is the preservation or even contraction of

the Region in order to create a really urban region. This would at least make the

poverty visible – and not concealed by averages that ignore the internal differences.

Furthermore, poor city residents would be given a say in the institutions that are

their mouthpiece, through which they can develop and defend their interests and

requirements. Perhaps this would enable redistribution from the Brussels suburbs to

the Brussels Region to be enforced; for example through local taxes that are partly

paid at the place of work instead of at the place of residence. The same reasoning is

also valid for the internal municipal differences. If we were to have around 30 homo-

geneous clearly-defined municipalities in Brussels, then as well as Sint-Joost-ten-

Node, there would be another fifteen that could epitomize and defend the interests

of the poor. The central districts and the most vulnerable inhabitants in the Region

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

9

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

would be supported on three levels: internally, the political representatives would

find it necessary to take account of the population without a vote as this is the larg-

est group; the problems of the central neighbourhoods would be represented more

strongly at the level of the region and also on a federal level; new local politicians

would build up expertise in defending these interests; finally, because of the (weak)

solidarity mechanism between the Brussels municipalities that is built into the Mu-

nicipalities Fund, the redistribution of resources between rich and poor municipalities

would increase.

In terms of administrative efficiency, the amalgamation of the smallest municipalities

could also obviously be considered or a redistribution of powers between munici-

palities and Region, or even collaboration between municipalities on certain matters

via intermunicipalities. Only the first option conflicts with the advantages of more,

homogenously defined municipalities in the Region. Increasing the number of Brus-

sels municipalities does not prevent powers or new forms of intermunicipal collabo-

ration from being redrawn. However, it seems important to examine these proposals

against the capacity of these institutions to guarantee redistribution at multiple

scales.

2. An open region with a new solidary policy

Solidarity should not only be organised on the correct scale levels, but it should also

have a political and social basis. Presently, Brussels is a divided city that lacks such

a basis. Brussels is no longer an ethnically homogenous, bilingual city and the ex-

ternalisation of a Belgian nation. However, the city is also no longer imprisoned in a

homogenous national culture that expects newcomers to integrate before receiving

solidarity. This lack of national culture means that Brussels appears as an ‘open’ city

to newcomers. Being incorporated in the urban community does not need to mean

that one acculturalises or assimilates. Policy needs to adjust to this reality: instead of

wanting to continue administering Brussels as a part of French-speaking Belgium or

Flanders, the Brussels openness should be exploited and a resolute choice should

be made for an international future.

However, openness also implies possibilities for a way out. Transnationality means

that people can also quickly withdraw themselves from solidarity links in one place

when they come out better in another place; situational solidarity is becoming less

common and is often being substituted by solidarity within transnational networks.

The cultural, institutional and socio-spatial structures make it perfectly possible to

shut oneself off to the poverty and misery of other groups. How the population of

Brussels, in all its diversity, can be encouraged to take part in solidarity and com-

mitment over and beyond group boundaries is an important challenge for the future,

where classical recipes of social structure and social cohesion will not be sufficient.

3. Working on the future generation’s future

Solidarity will be essential for safeguarding the future of Brussels. The Brussels

translational population is pre-eminently young and therefore forms the future of the

city. However, an important number of these young people are also poor, receive

insufficient schooling, are not able to find work and live in impoverished conditions.

An open city not only has a cultural significance, but also means that everyone re-

ceives sufficient chances for personal development and for climbing up the social

ladder. Training, employment and housing are therefore the key sectors.

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

10

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

This means that Brussels politicians need to pay less attention to the quantitative

aspects of job creation, and focus more on the quality of the jobs: which jobs do we

want in Brussels for Brussels residents? This also calls for deliberate investment in a

fundamental quality and affordability of housing and that gentrification, rather than

being a threat to the poor inhabitants of the inner city, should be the basis of a redis-

tributive policy on a regional level. The combination of soft gentrification (in which

newcomers share the diversity of the city with the existing population) and social

housing development in the same neighbourhood offers perspectives for improving

access to services including education. This type of social mix is a possible strategy

for creating a basis for a balanced spatial distribution of services (collective con-

sumption) and equal access to these services. This would enable the social and

ethnic segregation to be tackled in schools. The provision of good schooling and

training, where multilingualism is seen as a trump card for an international city,

where newcomers are actively taken care of and where equal opportunities are

given as much attention as performance, are all essential for guaranteeing the

openness of Brussels in the future.

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

11

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.

References

FAVELL A. (2001) Free movers in Brussels Brussels: a report on the participation

and integration of European professionals in the city, report for the Brussels-Re-

gion Government, IPSoM Working Paper 2001/7, Katholieke Universiteit Brus-

sel, Nov 2001, pp.81.

Observatorium van gezondheid en Welzijn van Brussel-Hoofdstad

http://www.observatbru.be

KESTELOOT C. (1999) "De la ségrégation à la division: l’évolution et les enjeux fu-

turs de la structure socio-spatiale bruxelloise", in WITTE E., ALEN A., DUMONT

H. & ERGEC R. eds. Het statuut van Brussel, Larcier, Brussel, p.155-189. also

available in english as: KESTELOOT C. (2000) "Brussels: postfordist polarization

in a fordist spatial canvas", in MARCUSE P. & VAN KEMPEN R. eds., Globalizing

cities: a new urban spatial order? Blackwell, Oxford, p.186-210.

VANNESTE, D., ABRAHAM, F., P. CABUS & L. SLEUWAEGEN (2003) Belgische

werkgelegenheid in een mondialiserende economie, Gent: Academia Press.

VANDERMOTTEN, C. (2009) "De Staat van de Brusselse economie twintig jaar na

de oprichting van het Gewest", in DEJEMEPPE e.a. (eds.), Brussel over 20 jaar,

p. 265-296.

THYS, S. (2009) "Werkgelegenheid en werkloosheid in het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk

Gewest: feiten en uitdagingen", in DEJEMEPPE e.a. (eds.), Brussel over 20 jaar,

p. 297-328.

VAN CRIEKINGEN M. (2006) "What is happening to Brussels' inner-city neighbour-

hoods?", Brussels Studies n°1,

http://www.brusselsstudies.be/PDF/Default.aspx?lien=EN_27_BS1_english.pdf&

IdPdf=27

KESTELOOT C., MISTIAEN P. & DECROLY J.M. (1998) "De ruimtelijke dimensie van

de armoede in Brussel: indicatoren, oorzaken en buurtgebonden

bestrijdingsstrategieen", in VRANKEN J., VANHERCKE B. & CARTON L., mmv.

VAN MENXEL G. . eds., 20 jaar OCMW, naar een actualisering van het maat-

schappijproject, Acco Leuven, p.125-155. Aussi en français : KESTELOOT C.,

MISTIAEN P. & DECROLY J.M. (1998) "La dimension spatiale de la pauvreté à

Bruxelles: indicateurs, causes et stratégies locales de lutte contre la pauvreté",

in VRANKEN J., VANHERCKE B. & CARTON L., mmv. VAN MENXEL G. eds.,

20 ans CPAS, vers une actualisation du projet de société, Acco Leuven,

p.123-153.

Brussels Studiesthe e-journal for academic research on Brussels

12

Chr. Kesteloot, M. Loopmans, “Citizens’ forum of Brussels. Social inequalities”,Brussels Studies, Synopsis nr. 16, 3 March 2009.