Voorbeschouwing Italiaanse verkiezingen: een dubbeltje op zijn kant

-

Upload

kbc-economics -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of Voorbeschouwing Italiaanse verkiezingen: een dubbeltje op zijn kant

-

7/30/2019 Voorbeschouwing Italiaanse verkiezingen: een dubbeltje op zijn kant

1/8

1 | I t a l i a n e l e c t i o n s

KBCECONOMIC RESEARCH (GCE)

ECONOMIC UPDATES

SIEGFRIED TOP

19FEBRUARY 2013

Update on Italy

Parliamentary elections: a close call

Executive summary

The elections of 24/25th February will be closely watched, as they are a good test for Italyswillingness to continue economic and fiscal reforms.

The Centre-Left (Bersani) is likely to win the nation-wide elected Chamber, and form a reform-friendly government with the Centre (Monti), although the Centre-Right (Berlusconi) has gained

momentum in the polls.

The specific electoral system may however complicate the government formation, as a coalitionrequires to win both the Chamber and the regionally chosen Senate. Financial uncertainty may

temporarily rise, if the new coalition would have no strong majority. Still, a post-election coalition

of the Centre-Left and Monti could also secure a majority in the Senate for the pro-reform parties.

Economic growth has disappointed again in Q4 (-0.9% qoq) and has contracted over the last 6quarters. Unemployment has risen to 11.2%. In the short term, fiscal consolidation and political

uncertainty puts domestic growth under pressure, but structural economic reforms should

enhance growth over the medium term. The higher unemployment rate can e.g. be partially

explained by a much higher labour participation.

Italy remains fiscally sustainable, as it is moving to a 5% primary balance surplus and will remaincovered by the ECBs OMT. A (partial) victory of Centre-Right could bring back the phantom of

2011, when Berlusconi reneged the ECB-deal and investors lost confidence in Italian debt.

However, Italian debt has been partially renationalized and Italian financial institutions and

citizens now hold over 63% of the debt. The high private Italian wealth still continues to provideboth a strong domestic investor base and gives the government sufficient taxing power.

-

7/30/2019 Voorbeschouwing Italiaanse verkiezingen: een dubbeltje op zijn kant

2/8

2 | I t a l i a n e l e c t i o n s

Update on Italy

Parliamentary elections: a close call

Elections or Euro-referendum?

On the 24th of February, Italy heads to the polls.

The elections were called two months earlier

than foreseen after the resignation of

technocrat Prime Minister (PM) Mario Monti,

who was just over a year in office. Monti had

lost his majority in the Parliament, after the

party of former PM Berlusconi withdrew its

support to the technocratic government late

2012, in prospect of the upcoming 5-yearlyParliamentary elections. These elections are

important both for Italy and the EMU, as they

can also be seen as a referendum for the

significant change in policy that took place

under Monti. His government introduced

various structural reform programmes in the

field of fiscal discipline, labour market, and

competitiveness (e.g. Salve Italia, Cresce Italia),

which helped to restore Italian policy credibility.

Since the start of the Monti reforms and the

announcement of the ECBs OMT-programme

(in which the ECB gave an implicit guarantee for

EMU governments debt), Italy has slowly

moved out of the market turmoil. European

leaders will thus closely watch the elections, in

the hope for a convincing victory of the pro-

reform parties. However, the Italian political

and electoral system has some specific

characteristics, that could lead to a less

favourable outcome, and pose a threat to the

ongoing reform.

A specific electoral system

Italy has a long tradition of political instability.

Between 1945 and 1994, 50 different

governments were formed, mostly coalitions of

3 to 4 parties, led by the strong Christian

Democratic Party. This changed after 1994,

when the Christian Democratic party collapsed

after several corruption allegations. Silvio

Berlusconi won the 1994 elections with a pre-

election made coalition (or cartel), and

gradually and with intermissions started to

dominate the Italian political landscape since.

Berlusconi also introduced a new electoral law,

which will despite attempts to reform it in

2012 again be applicable in the upcoming

elections.

First of all, the current electoral law is strongly

biased towards large parties and coalitions, as

there are high electoral thresholds and a

winner-takes-it-all principle is used both in the

lower (Chamber) and upper house (Senate). The

Italian Chamber is elected on a nation-wide

basis and has a threshold of 4% for individual

parties and 10% for coalitions (and 2% for

parties inside coalitions). The party/coalition

that wins the elections automatically receives

54% of all seats in the Chamber, votes of partiesbelow the threshold are proportionally divided.

In the Senate, seats are allocated on a regional

principle. Each of the 20 Italian regions can vote

for a party or coalition, with a high threshold of

8% for parties and 20% for coalitions (and 3%

for parties inside eligible coalitions). If a

coalition does not meet the threshold, the

individual party threshold (8%) will count. The

winner in each region also obtains 55% of the

seats allocated to that specific region. It is thusnot unlikely that the majority in the House and

the Senate differ.

This different election approach in the Chamber

and the Senate pose a second issue. Italy has a

form of perfect bicameralism, meaning that

both branches of Parliament have comparable

-

7/30/2019 Voorbeschouwing Italiaanse verkiezingen: een dubbeltje op zijn kant

3/8

3 | I t a l i a n e l e c t i o n s

powers. Both assemblies can introduce new

laws, and need to vote for the laws introduced

by the other assembly. A new government thus

also needs a majority in both houses.

This electoral system has allowed a certain

stability, as no coalition talks were necessary (a

voter chooses a pre-made coalition), and the

average lifetime of governments increased.

However, it has also led to a strong increase in

often quite diversified coalitions and

consequently single-coalition governments,

which, intrinsically, have made the political

landscape even more fragmented, as most

coalitions proved not to be stable and coalition-

structures made the number of new, issue-

specific parties boom.

A final specificity of the electoral system is the

voting right. Every citizens can vote, even

Italians who live abroad (a limited number of

seats are allocated to them). However, the vote

is officially called a duty, yet not compulsory.

Although historically the participation rates are

high (~80%), the non-voting party is now

estimated at around 35/40%.

The current electoral landscape

As the political system strongly benefits

coalitions, most parties have allied themselves

in three large blocks. Next to that, two smaller

parties may also have an influence on the

election result.

Centre-Left (PD/SEL): The Democratic Partyof Pier Luigi Bersani consists of leftist and

green parties, and has been leading in the

polls since early 2012. The party is ingeneral supportive of the reform

programmes started by Monti.

Centre-Right (PdL/LN): The Freedom Partyof Angelino Alfano has renewed its alliance

with the Lega Nord, with Silvio Berlusconi

again as front-runner, although he is not a

candidate to become the new Prime

Minister. Most likely candidates are Alfano

or former finance minister Guido Tremonti.

PdL from its side wants to revert most of the

Monti reforms, while Lega Nord looks for

more autonomy of the (northern) regions.

Monti for Italy coalition: Before endDecember, it was uncertain whether Monti

would have another run for PM. Monti was

asked by PdL to lead a broad right

coalition, but refused and chose for a

coalition with smaller, centrist parties who

would support his reform-friendly, but

rather conservative programme.

5 Star Movement: This anti-establishmentparty of comedian Beppe Grillo obtained

some strong results in the communal

elections of 2012. His programme is very

anti-EU and anti-Euro, and he was long the

most influential opponent of the

technocratic Monti-government, but lost

momentum as Berlusconi came to the fore.

Still, M5S will probably be well over the

thresholds and obtain seats in both houses,

but is unlikely to join any coalition.

Civil Revolution: a new coalition of leftistand green parties, that stand for new

politics, and have made anti-corruption as

their main programme point. PM candidate

Antonio Ingroia is a famous anti-mafia and

anti-drugs investigator. Civil Revolution is

likely to take away some votes from the

Centre-Left, but is unlikely to be above the

thresholds.

What will be the outcome?

Up to December 2012, the elections seemed to

be a non-issue, as the Centre-left was well in the

lead (up to 40% of votes in polls), while the

centre and the right of the spectrum were very

divided. However, this outlook changed as new

coalitions were formed in the months ahead of

-

7/30/2019 Voorbeschouwing Italiaanse verkiezingen: een dubbeltje op zijn kant

4/8

4 | I t a l i a n e l e c t i o n s

the election and opinion polls started to suggest

that the Centre-Right found back its historical

strength in the person of former PM Berlusconi

(see graph 1). From the other hand, the Centre-

Left lost some support as some of its candidates

are linked to the Banca Monte dei Paschi-scandal, and another broad left coalition (Civil

Revolution) gained some strength with its anti-

corruption programme. The recent two months,

Berlusconi started a large media-offensive,

accusing Monti of pushing Italy into a severe

recession and putting heavy financial burdens

on the Italians. The economic crisis has stirred

more regionalist sentiments in the north, adding

to the success of Centre-Right (with Lega Nord).

From the other side, both business leaders and

more conservative forces (e.g. the catholicvote) continue to support Monti. Since the 9

th

of February, however, a polls black-out began,

so that all eyes will now be on the initial results

on Monday the 25th

.

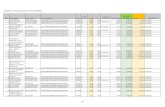

Graph 1: Polls show momentum for Centre-Right

In the House of Representatives, we still expect

a win of the Centre-Left. This would thus secure

a majority in the House, which may be

reinforced if Bersani asks Monti to join his

coalition. Centre-Left would thus have a large

majority in Parliament. However, the picture is

more complicated in the Senate. Regional polls

suggest that some (mostly northern) regions will

see a Centre-Right victory (e.g. Veneto). There

are also some important swing states, e.g. like

Lombardy, Campania and Sicily, were it is a very

close call. Given the majority system (55% of

seats go to the winner), it is not unlikely thatCentre-Right outnumbers Centre-Left in the

Senate. What is more, given the high threshold,

Montis coalition is unlikely to obtain a high

number of seats in the Senate. However, his

individual party may cross the single party

threshold and thus still obtain a limited number

of seats in the Senate (probably less than 10% of

seats).

An import factor will thus be the non-voting

party. The protest vote remains undecided,

but is traditionally more or less moderate.

Although Berlusconi and more radical coalitions

have been trying to capture these votes, it is our

assumption that in the end, the Centre will

capture more seats than the current polls

suggest, which would be enough to provide a

majority for Center and Center-Left in the

Senate too.

Financial uncertainty may rise

Under Monti, a broad range of reforms was

announced and (partially) implemented. Mainly

in the first 6 months of his legislature, significant

improvement was made in restoring fiscal

sustainability and introducing growth-friendly

measures. This has partially restored investors

confidence in Italian government bonds,

although bond spreads have remained very

elevated until the Summer of 2012, as the

Spanish financial sector and government were

under severe distress. This changed significantly

after the announcement of the Outright

Monetary Transaction (OMT)-programme of the

ECB, which give an implicit central bank

guarantee to government bonds, at least as

these governments comply to the Fiscal

Compact and, if assistance is effectively needed,

demand a precautionary programme from the

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Week to 10jan

Week to 17jan

Week to 24jan

Week to 1feb

Week to 8feb

Five Star Movement

Monti for Italy

Centre-Right (PdL and Lega Nor t)

Centre-Left (PD/SEL)

* Weekly average of all recognized polls

-

7/30/2019 Voorbeschouwing Italiaanse verkiezingen: een dubbeltje op zijn kant

5/8

5 | I t a l i a n e l e c t i o n s

ESM and accept the fiscal and economic reform

conditionality involved. This statement made

the Italian (and Spanish) bond spreads relax (see

graph 2), and helped to restore market access.

However, the uncertainty around the Italian

elections has partially revived the fears about

the Italian willingness to reform and the

sustainability of Italian government debt, which

stands at 126% of GDP. Most recently, fears

have also mounted about the Italian real

economy, which remains in a depressive state.

Graph 2: Bond yields remain volatile

Worries about the economy and

continuation of reforms

Over the last quarters, the Italian economic

situation has further deteriorated. In the 4th

quarter, the Italian GDP contracted again by

0.9%, the 6th

negative quarter in a row. Italian

GDP has now fallen deeper than in the recession

of 2008-2009, and last years recession was

deeper than e.g. in Spain. This was mainlydriven by weakness in consumption and

investment, as was also reflected in weak

consumer and producer confidence over the last

year.

Graph 3: Economic growth remains depressed

(Real GDP growth Q4 2007=100)

Since early 2013, producer confidence picked up

again in Germany, and, to a lesser extent, inSpain, in line with a world-wide improvement in

producers and exporters confidence. However,

French and Italian producer confidence

indicators continued to move downwards,

suggesting that their economies will not recover

in the first quarter of 2013 yet. In our base

scenario, the Italian economy will turn the

corner in the second half of 2013.

Graph 4: Producer confidence (PMI composite) still

weak

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Government10Ybondyields,in%

Germany

Italy

Spain

92

94

96

98

100

102

104

Germany France

Italy Spain

40

45

50

55

60

65

Above50=expansion,below50=contraction Spain Italy

France Germany

-

7/30/2019 Voorbeschouwing Italiaanse verkiezingen: een dubbeltje op zijn kant

6/8

6 | I t a l i a n e l e c t i o n s

The main culprit for the recession remains weak

domestic demand. The reforms implemented by

the Monti government will have positive effects

in the medium term, but on the short term, they

have negative effects on the real economy. The

increase in the standard VAT rate (from 20% to21%, halved from the original 2%), in excise

duties on fuel and in taxation on property are

necessary for fiscal consolidation, but weigh

negatively on consumption, and are one of the

main themes in the elections. Berlusconi already

announced to pay back part of these taxations,

in order to give the Italians back money to

spend.

Other reforms, such as the labour market

(Fornero-) reform, the liberalization of closed

services and product market regulation, and the

pension reform should have a positive impact

on the medium-term, but are hard to explain to

the electorate. The immediate impact of the

greater flexibility through labour market reform

leads e.g. to a higher unemployment rate, which

has risen from around 9% at the start of Montis

mandate to 11.2% end 2012. This increase can

however to a large extent be explained by the

increase in labour participation, particularly

amongst women, which in the medium-termwill be beneficial to economic growth.

Graph 5: Unemployment rises as labour force

increases

More reforms are needed still, but the Centre-

Left already announced to resist excess

flexibility, thus partially reversing the Fornero-

reform. Another measure to boost economic

growth is the enhancement of productivity and

labour efficiency, as Italian competitiveness still

clearly lacks behind other EMU countries. E.g.

Spain, Ireland and Greece realized serious wagemoderation over the recent crisis years. The

recent increase in producer confidence and

export demand in Spain and Ireland may reflect

this improved competitiveness.

Graph 6: Unit labour costs remain high in Italy

Since 2008, relative unit labour costs (ULC)decreased by over 20% in Ireland and 15% in

Spain, while those in Italy sunk by merely 5%

(see graph 6), thus remaining in line with France

and Germany (of which ULC in the latter had

decreased significantly in the 5 preceding years).

Late 2012, a new contract was signed between

the social partners, the Guidelines to increase

productivity and competitiveness in Italy. Under

these guidelines, national collective bargaining

agreements will reflect economic trends andhave no implicit indexation. Moreover, a

stronger emphasis is put on individual or local-

level contracts, which gives employers greater

flexibility. The reduction in taxation of labour

will also decrease labour costs for firms. Further

reforms to improve competitiveness could be

expected if the Centre-Left (with or without

22000

22500

23000

23500

24000

24500

25000

25500

26000

Workersin'1000

Labour force

Employment

75

80

85

90

95

100

105

Q12008=10

0

Italy Spain

Ireland Germany

France

-

7/30/2019 Voorbeschouwing Italiaanse verkiezingen: een dubbeltje op zijn kant

7/8

7 | I t a l i a n e l e c t i o n s

Monti) comes to power, albeit economic

reforms will probably proceed at a slower level.

Table 1 : Economic outlook

2012 2013 2014

GDP growth (in %) -2.2 -1.2 1.0Unemployment rate 10.8 11.4 11.3

Current account

balance (in % GDP) -1.4 -1.3 -1.1

Fiscal sustainability under scrutiny

One of the main accomplishments of the Monti

government was bringing back in line public

finances. Consecutive reforms brought the

Italian primary balance (net of interestpayments) from 0.1% of GDP in 2010 to an

expected 3.8% surplus in 2013, and 5% in 2015.

A new constitutional fiscal rule (golden rule)

should further strengthen discipline. Through

this fiscal adjustment, government debt, which

stood at around 126.4% of GDP, should be

stabilized, and is expected to decline below

120% in 2015. Moreover, announced asset sales

should be worth around 1% of GDP yearly, and

allow an even faster debt reduction.

Graph 7: Government finances sustainable, but no

room for deviations (all in % of GDP)

Financial markets have given Italy the benefit of

the doubt in 2012. One of the important

features of Italy differentiating it from other

peripheral economies - is the very high net

wealth of the Italian residents. Net foreign

liabilities are stable around 20% of GDP,compared to the 90 to 100% negative NIIP in

Spain, Portugal, Ireland and Greece. Last year,

the issuance of a solidarity bond (similar to the

Leterme bond in Belgium) was a success, and

indicated that Italian debt can be rolled-over

using these domestic savings. Italian banks

(using the LTROs) also emerged as major

investors in sovereign bonds. As a result, only

36% of Italian debt is now non-domestically held

(down from 52% in 2010).

However, deviations from the current targets (a

sustained primary balance surplus of 5% of GDP)

will not be tolerated by investors in Italian debt

and the European Commission, Council and the

ECB. The latter is particularly important, as the

ECB has implicitly guaranteed the debt of

European problem countries (mainly Italy and

Spain) through its Outright Monetary

Transactions (OMT)-programme. A deviation

from fiscal austerity and structural reforms after

the elections could bring Italy back to thesituation of August 2011, when the ECB bought

Italian debt under its former SMP-programme

with similar conditions. At that time, PM

Berlusconi reneged the deal with the ECB, that

then had to refrain from further action, with a

rapid loss of investor confidence as a result.

However, under our base scenario, a win of

Centre-Left with potential support by Monti and

the Centre, the current sustainable fiscal stance

will be retained. In that case, the ECBs OMT

remains as a credible backstop in case the

eurocrisis flares up again.85

90

95

100

105

110

115

120

125

130

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6Net borrowing

Cycl.-adj. primary balance

Gross gov. debt (RHS)

-

7/30/2019 Voorbeschouwing Italiaanse verkiezingen: een dubbeltje op zijn kant

8/8

8 | I t a l i a n e l e c t i o n s

Disclaimer

This publication is prepared by KBC Group NV, or related KBC-group companies such as KBC Bank NV,KBC Asset Management NV, KBC Securities NV (hereafter together KBC).

The non-exhaustive information contained herein is based on short and long-term forecasts forexpected developments on the financial markets and the economy. KBC cannot guarantee that these

forecasts will materialize and cannot be held liable in any way for direct or consequential loss arisingfrom any use of, or reliance on, this document or its content.

This publication is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended to be an offer, or thesolicitation of any offer, to buy or sell the securities or other financial products/instruments referred toherein. The document is not intended as personalized investment advice and does not constitute arecommendation to buy, sell or hold investments described herein.

This publication contains KBC proprietary information. No part of this publication may be reproduced inany manner without the prior written consent of KBC.

The information, opinions, forecasts, and estimates herein have been obtained from, and are basedupon, sources believed reliable, but KBC does not guarantee that it is accurate or complete, and itshould not be relied upon as such. All opinions and estimates constitute a KBC judgment as of the dateof the report and are subject to change without notice.

This publication is provided solely for the information and use of professionals (such as journalists,economists, and professional investors) who are expected to make their own investment decisionswithout undue reliance on this publication. Professional investors must make their own determinationof the appropriateness of an investment based on the merits and risks involved, their own investmentstrategy and their legal, fiscal and financial position.