Carolus Linnaeus 1707 - 1778 · Het systeem van naamgeving werkte Linnaeus later uit, in 1751, in...

Transcript of Carolus Linnaeus 1707 - 1778 · Het systeem van naamgeving werkte Linnaeus later uit, in 1751, in...

Carolus Linnaeus 1707 - 1778

Carolus Linnaeus werd geboren op 23 mei 1707 in het plaatsje Rasholt in de Zuid-Zweedse provincie Småland. Als kind al had hij belangstelling voor plant en dier, aangezet door zijn vader en moeder, Nils Ingemarsson en Christina Brodersonia. Zijn vader was dominee, zijn moeder een domineesdochter. Deze eenvoudige achtergrond en de weidse vlucht van zijn wetenschappelijk werk hebben hem een bijna mythische reputatie verleend.

De Zweedse samenleving waarin hij geboren werd, was gelovig, agrarisch, met een open blik en gekleurd door het noordeuropees klimaat met korte krachtige zomers en lange strenge winters. Kern van het religieuze en seculiere leven waren kerk en pastorie. De gloriedagen van het Koninkrijk Zweden waren toen voorbij, zijn macht en invloed verzwakt.

Linnaeus leefde in het tijdperk van de Verlichting. Deze periode in de ontwikkeling van de Europese cultuur duurt van ± 1650 tot aan de Franse revolutie, die in 1789 begint. Het kenmerk van de geest van de Verlichting is, dat de ratio, de rede, het verstand, erkend wordt als het primair maatgevend instrument in onderzoek en waarheidsvinding, en niet langer het dogma. Ook Linnaeus is wat dat betreft een kind van zijn tijd, getuige zijn classificatie van organismen, die hij stoelde op sexualiteit wat toen betrekkelijk nieuw en omstreden was.

In zijn jeugd heette hij Carl Nilsson. Nu kennen wij hem vooral onder de naam Carolus Linnaeus. En ook wel als Carl von Linné, de naam die hij aannam bij zijn verheffing in de adelstand in 1757. Daarnaast werd hem de naam ‘Vorst der botanici’ toegedicht. En ook: ‘Plinius van het Noorden’, met een verwijzing naar de romeinse militair, letterkundige en amateur-wetenschapper, geboren AD 23. Of ‘de tweede Adam’ naar de bijbelse Adam die in het paradijs plant en dier een naam gaf.

Wij kennen hem ook als L. Deze hoofdletter met een punt erachter is de toevoeging aan de wetenschappelijke naam van plant of dier. Bijvoorbeeld, Quercus robur L.. Dit is de zomereik. De strekking van deze toevoeging L., de auteursnaam, is dat Linnaeus als eerste deze boomsoort beschreef en er de wetenschappelijke naam aan gaf. Nu, 300 jaar na Linnaeus’ geboorte, telt de auteurslijst ongeveer 40.000 namen.

Eén plantje vernoemde Linnaeus naar zichzelf. Het heet Linnaea borealis L.. In Nederland is het zeer zeldzaam. Hij ontdekte het op zijn reis door Lapland in 1732 en beschreef het in zijn Flora lapponica. Met dit linnaeusklokje wordt hij vaak afgebeeld o.a. op het schilderij dat door Martin Hoffman in 1737, tijdens Linnaeus’ Nederlandse periode op het buiten Hartecamp geschilderd werd. Niet zoals gedacht en verwacht werd, zou Carl in dezelfde roeping treden als zijn vader en theologie gaan studeren. In plaats daarvan werd het medicijnen. Plantkunde bestond in die tijd nog niet als zelfstandige studie. Het maakte deel uit van de geneeskunde. Een geneeskunde die wij primitief zouden noemen en die nog met één been in de traditionele en soms bijgelovige volksgeneeskunde stond, getuige Linnaeus’ aantekeningen van zijn eerste studies die een mengeling zijn van volksgeloof en /wijsheid en modern inzicht en observatie.

Na zijn gymnasiumtijd in Växjo gaat hij allereerst, in 1727, naar de universiteit van Lund. Het jaar daarop naar de oudere universiteit van Uppsala. Daar studeert hij tot aan zijn vertrek naar de Nederlanden in 1737. Tijdens die periode van ongeveer tien jaar maakt hij studiereizen naar de Zweedse provincies Lapland en Dalarna. Het manuscript met de vrucht van zijn reizen en studies in de wereld der natuur - planten, dieren en gesteenten - neemt hij mee als hij, met Petrus Artedi, naar de Republiek reist. Hij arriveert daar op 17 juni 1735 in Harderwijk, waar een kleine universiteit was. Die zelfde maand nog promoveert hij daar tot doctor in de medicijnen met een dissertatie over koorts.

De naam van het manuscript dat hij meenam vanuit Zweden is: Systema Naturae. De eerste gedrukte versie ervan verschijnt in 1735, als hij in Nederland is. De visie, daarin neergelegd en nadien gepreciseerd, doorschijnt zijn gehele werk. Deze visie wordt gekenmerkt door het principe ‘divisio et denominatio’. Dat wil zeggen dat het onderzochte wordt verdeeld en geordend op grond van verschillen en overeenkomsten en dat aan de deelverzamelingen van het systeem een naam wordt gegeven. Deze deelverzamelingen worden taxa genoemd; enkelvoud: taxon.

Bij zijn indeling van het rijk der planten baseerde hij zich primair op overeenkomsten en verschillen in de voortplantingsorganen, de bloemen met hun meeldraden en stampers. Dit sexuele systeem werd aan het eind van de zeventiende eeuw ontdekt. Linnaeus heeft erop voortgebouwd en het zijn gehele leven toegepast al was hij zich bewust van de kunstmatigheid en onvolkomenheid ervan. In moderne classificatiesystemen wordt het criterium ‘sexualiteit’ niet langer als maatgevend toegepast.

Een eeuw na Linnaeus, in 1865, formuleerde Johann Mendel de wetten van de erfelijkheid. Daarvóór, in 1859, publiceerde Darwin zijn ‘On the origen of species by means of natural selection’, waarin de evolutietheorie ontvouwd werd. En een eeuw daarna, in 1953, werd de de struktuur van het dna, door Watson en Crick ontdekt, de dubbele helix waarop de erfelijke code van organismen is geschreven. Tezamen waren en zijn zij richtingbepalend voor de wetenschappelijke visie op de levende natuur. Het systeem van naamgeving werkte Linnaeus later uit, in 1751, in zijn hoofdwerk, de Philosophia botanica. In dit invloedrijke werk formuleerde hij het principe van de binomiale nomenclatuur dat het fundament is geworden van de de taxonomie - de wetenschap van het naamgeven. Het houdt in dat de latijnse, wetenschap-pelijke naam van een soort - een plant, dier of ander organisme - bestaat uit twee delen. Bijvoorbeeld, Triticum spelta L., dit is spelt, een tarwesoort. Of Brassica oleraceae L., kool.

In 1734 verloofde hij zich met Sara Lisa Moraea, dochter van mijnarts Moraeus in Falun. Dit engagement stelde Linnaeus materieel in staat zich internationaal te oriënteren en de centra van wetenschap in West Europa te bezoeken. De Republiek was in het tijdperk na de gouden eeuw één van deze centra. Met ambitie, vaardigheid en een aangeboren neiging tot het nuttige verwierf hij daar een vooraanstaande wetenschappelijke positie.Hij ontmoette er eminente collega’s, waaronder Boerhave, en zag zijn werk gepubliceerd, daarin bijgestaan door de natuurhistoricus Johan Burman. Hij maakte reizen naar Frankrijk en Engeland, maar verbleef meestal als lijfarts en hortulanus op Hartecamp. Hij schreef er de Hortus Cliffortianus, naar George Clifford, bankier en eigenaar van het buiten. Petrus Artedi kwam om bij een nachtelijke val in het water van een Amsterdamse gracht. Diens publicatie, Ichtyologia, werd in 1738 postuum door zijn vriend bezorgd.

In 1739 trouwde hij, kort na zijn terugkeer vanuit Holland. Zijn dralen daarbij zal ertoe bijgedragen hebben dat het met de romantiek in het huwelijk niet zo vlotte. Over zijn terugkeer naar Zweden in 1738 schrijft hij nochtans: ‘reisde rechtstreeks naar Falun om zijn zoetelief te begroeten, die haast vier jaar op haar beminde Odysseus had gewacht’. Dit citaat kenmerkt Linnaeus door zijn gebruik van de derde persoon enkelvoud, ook als hij over zichzelf schrijft. En door zijn link naar de klassieke mythologie. Linnaeus was een begaafd en productief schrijver van publicaties, dissertaties, brieven en reisverslagen. Het meeste ervan in zijn moedertaal. Naast Zweeds sprak Linnaeus geen levende taal.

Na zijn terugkeer bleef hij in Zweden, tot aan zijn dood in 1778. Eerst was hij arts in Stockholm. Enkele jaren daarna, in 1741, werd hij benoemd tot professor in de geneeskunde te Uppsala èn werd hij directeur van de botanische tuin inclusief de menagerie. In de jaren erna bezette hij tal van wetenschappelijke sleutelposities, onderzoekend, educatief en bestuurlijk. Hij maakte nog drie studiereizen. Zijn talrijke leerlingen zwermden uit over de wereld. Hij had één zoon, Carl. Deze volgde hem op, overleed echter kort na zijn vader.

Carolus Linnaeus 1707 - 1778

Carolus Linnaeus was born on the 23th of May of the year 1707 in the village of Rasholt in the South Swedish province of Småland. From his birth and childhood on he was nurtured with an interest in nature. His father’s name is Nils Ingmarsson, his mother’s Christina Brodersonia, he a parson and and she a parson’s daughter. This unsophisticated background coupled with his far reaching influence on science gave him an almost mythical reputation.

The Swedish society he was born into was religious, agricultural, with an open mind, coloured by the North European climate with bright and intense summers and long dark winters. The nuclei of religious and secular life were church and parsonage. Politically seen, the days of glory of the kingdom of Sweden were over, it’s power and influence weakened.

Linnaeus lived in the age of Enlightenment. This period in the development of European culture begins around 1650 and ends with the French revolution in 1789. The sign of the spirit of the Enlightenment is the ratio, the reason, the sense being recognized as the prime guiding instrument in research and finding the truth, and no longer the dogma. In this respect Linnaeus too is a child of his age, considering his classification of organisms which he rooted in sexuality which in those days was a relatively new and controversial concept.

In his youth he was called Carl Nilsson. Now, above all, we know him as Carolus Linnaeus. And also as Carl von Linné, which name he adopted when he was elevated to nobility in 1757. He was also given the name ‘Ruler of botanists’. And: ‘Plinius of the North’, which refers to the roman soldier, writer and scientist, born AD 23. Or ‘the second Adam’, the first one being the Adam who, in paradise, gave the amimals and plants a name.

We also know him as L.. This capital letter followed by a dot is an addition to the latin, scientific name of a plant or animal. E.g. Quercus robur L.. This is the English oak. The meaning of the addition, the author’s name, is that Linnaeus defined this tree- species and gave it it’s scientific name. Now, 300 years after Linnaeus’ birth, the list with authors, has about 40.000 names.

There is one little plant which Linnaeus named after himself. It is called Linnaea borealis L.. In the Netherlands this is a very rare plant. He discovered it on his travel to Lapland and described it in his Flora lapponica. With this twinflower he has often been depicted, among others on the painting Martin Hoffman made in 1737 when Linnaeus stayed at Hartecamp, near Leiden and Amsterdam.

According to tradition, Linnaeus should have studied theology and become a parson, as his father was. Instead, helped and stimulated, he took up medicine. Botany was subordinate to medicine in those days. We would call this medicine primitive, standing with one leg in traditional and sometimes supersticious popular medicine, witnessing Linnaeus’ virginal notes which are a compound of popular belief and wisdom and modern vision and observation.

After his schoolyears at the Växjo gymnasium he enters Lund university in 1727. The next year, in the more ancient university of Uppsala. There he studies until his stay in the Netherlands in 1737. In those ten years, he makes travels to the Swedish provinces of Lapland and Dalarna. The manuscript with the fruit of his studies and travels in those years on plants, animals and minerals, he takes with him when he goes to the Netherlands, together with Petrus Artedi. On the 17th of June he arrives at Harderwijk, the seat of a university. That same month he receives his promotion with a medical thesis on fever.

The name of the manuscript he took with him from Sweden is: Systema Naturae. The first printed version comes out in 1735, when he is in the Netherlands. It’s vision and revision are a lead in his work and life. A main principle is the ‘divisio et denominatio’. Which means divide and give a name. What is examined, on the basis of similarity and difference, is given a name and a place in the appropriate taxon, a grouping of similar organisms.

In his classification of the world of plants he grounds himself on similarities and differences of the sexual organs, the flowers with their stamen and carpels. This sexual system was discovered at the end of the 17th century. Linnaeus built further on it and applied it all his life though he was aware of it’s artificiality and incompleteness. In modern systems of classification this criterion of sexuality is no longer the measure of things.

One century after Linnaeus, in 1865 Johann Mendel formulated the laws of heridity. About the same time, in 1859 Darwin published his ‘On the origen of species by means of natural selection’ in which he unfolded the theory of evolution. And again, one century later, in 1953, Watson and Crick discovered the structure of the dna, the double helix on which the genetic code of organisms is written. Together they set the trend for the scientific vision on living nature.

In his main work, the Philosophia botanica, published in 1751, Linnaeus elaborated his system of giving names. In this influential book he formulated the principle of binomial nomenclature which became the foundation of taxonomy - the science of giving names. It implies that the latin, scientific name of a species - a plant, an animal or other organism - is composed of two parts. E.g. Triticum spelta L., this is spelt, a wheat species. Or Brassica oleraceae L., which is cabbage.

In 1734 he became engaged to Sara Lisa Moraea, daughter of the doctor of the Falun mine. This engagement materially enabled

Linnaeus to have an international outlook and visit the centres of science in Western Europe. In this period after the golden age, the Netherlands were one of these centres. With ambition, skill and an inborn tendency for the usefull, he obtained a prominent scientific position there.

Here he met eminent colleagues, among whom Boerhave and saw his work published with the help of the natural historian Johan Burman. He travelled to France and England but most of the time stayed as a personal physician and conservator at the Hartecamp manor. There he wrote his Hortus Cliffirtianus, named after George Clifford, banker and owner of the estate. Petrus Artedi died after fatally falling into the water of an Amsterdam canal. After his death his publication, Ichtyologia, was attended to by his friend.

Shortly after returning from the Netherlands he married. Probably having postponed this too long was a reason why romance in the marriage was not a big issue. Nevertheless, on his return to Sweden he writes: ‘travelled straight away to Falun to meet his sweetheart, who had been waiting for almost four years for her beloved Ulysses’. This quote characterizes Linnaeus, using the third person singular when he is writing about himself. And also by his linking to classical mythology. Linnaeus was a gifted and productive writer of publications, dissertations, of records of his journeys and of letters. Most of them in his native language. Save Swedish, Linnaeus did not speak another living language. After he had returned he stayed in Sweden until he died in 1778.

At first he was a physician in Stockholm. A few years later, in 1741, he was appointed professor of medicine in Uppsala and director of the botanical garden including the menagerie. In the following years he held many scientific key-positions in research, education and administration and made three more study travels. His numerous pupils swarmed off all over the world. He had one son, Carl, who succeeded his father, but died soon after him.

Brassica

Brassica, kool, is één van de geslachten in de familie der mosterd-achtigen, de Brassicaceae. Al in de antieke wereld was het een belangrijk land- en tuinbouwgewas en dat is het nog steeds. De origine ervan ligt in Europa en Azië. Nu wordt het overal ter wereld geteeld. Vele soorten binnen het geslacht zijn voedsel voor mens en dier. Andere worden geteeld als grondstof voor biobrandstof.

Kool is één- of tweejarige, soms overblijvende, kruidachtige plant. Eénjarig wil zeggen dat de plant in één groeiseizoen de volledige levenscyclus van kiem tot zaad doorloopt en daarna afsterft. Een tweejarige doet daar twee jaar over waarbij in het eerste jaar een bladrozet wordt gevormd dat in het erop volgende jaar uitgroeit tot de volwassen plant. De bloem is viertallig, reden waarom de familie der Brassicaceae ook wel de Cruciferae, kruisbloemigen, wordt ge-noemd. De kleur van de bloem is geel of wit. De bloem is twee-slachtig wat betekent dat de bloem zowel mannelijke en vrouw-elijke voortplantingsorganen bevat, de meeldraden en de stampers.

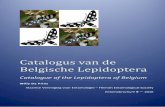

Een model van de verwantschappen binnen het soortenrijke geslacht Brassica staat bekend als de driehoek van U, vernoemd naar Nagaharu U. Dit is de japanse naam van Woo Jang-choon, een koreaans botanicus die in Japan onderzoek deed. In 1935 publiceerde hij zijn theorie over evolutie en relaties van het geslacht Brassica. Hij schetst daarin een driehoek, met op de hoekpunten Brassica oleracea L., Brassica rapa L. en Brassica nigra L., elk met hun specifiek genoom, dat resp. 18, 20 en 16 chromosomen telt. De kruising van telkens twee van deze soorten heten Brassica napus L., Brassica juncea L. en Brassica carinata A. Br.. Ze zijn de genetische combinaties van de drie eerstgenoemde soorten en hebben resp. 38, 36 en 34 chromosomen.

Het geslacht Brassica omvat meer dan dertig soorten. Eén van deze soorten, Brassica oleraceae L., is de bron van veel van onze

consumptiekool, bijvoorbeeld rode kool en spruitjes. Het scala van vormen, kleuren en smaken binnen de soort Brassica olercea L. is zó groot dat er zeven groepen in onderscheiden kunnen worden. Deze diversiteit ontstond in de loop der millennia door kruising en selectie, die deels natuurlijk en spontaan plaatsvond en voor een ander deel door menselijk handelen werd bereikt. Van de zeven groepen is Brassica oleracea var. capitata L. de grootste.

De naam Brassica oleracea var. capitata L.. is samengesteld volgens het systeem dat Linnaeus in 1751 in zijn Philosophia botanica publiceerde. Brassica, het traditionele latijnse woord voor ‘kool’, is de naam van het geslacht; oleracea, wat ‘groenteachtige’ betekent, is de soortaanduiding. Het var. is de afkorting van het woord variëteit. Dit taxon, dat wil zeggen deze onderscheidbare en benoemde deelverzameling, bevindt zich één trede lager in de classificatie dan het taxon species, soort. Het latijnse capitata betekent ‘met een kop voorzien’.

De gewoonte om wetenschappelijke werk te schrijven in het latijn begon ongeveer 1500, met de herontdekking van de klassieke oudheid en de opkomst van het humanisme. Wetenschappers met een verschillende moedertaal konden hierdoor hun werk uitwisselen.Tijdens de Verlichting, tweehonderd jaar later, begint de tegen-beweging die het schrijven in de landstaal beoogt. Voor het systematische werk van Linnaeus bleef het latijn het meest geschikt.

De grote verschillen in vorm, kleur, smaak, teelt en resistentie tegen ziekten en plagen, van de diverse koolsoorten en -rassen wekken verbazing als je bedenkt dat dit alles uit dezelfde bron voortkomt. Alleen al binnen de groep Brassica oleraceae var. capitata L., wat met een algemene naam sluitkool wordt genoemd, zijn er honderden rassen. Tot deze groep behoren de rodekool, witte kool, boerenkool en savoiekool. Wat deze groep onderling verbindt is dat geselecteerd wordt op het blad als eetbaar bestanddeel van de plant. In een tweede groep, Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera DC., ligt de nadruk op de ontwikkeling van de zijknoppen op de stengel, met spruitkool als resultaat. In de groep

Brassica oleracea var. botrytis is het een opeenhoping van onontwikkelde bloemknoppen die gewenst is. Bloemkool behoort tot deze groep. Koolrabi, tenslotte, behoort tot de groep Brassica oleraceae var. gongyloides. In deze groep is het de stengel die verdikt werd tot een met blad bezette knol. De verscheidenheid van vorm, kleur, en smaak waarover wij nu kunnen beschikken kwam tot stand door menselijke kennis, vernuft, geduld en economisch handelen. De eigenschap van een bepaald ras, de speciale combinatie van erfelijke eigenschappen die door kruising en selectie werd bereikt, is echter niet stabiel. Bij spontane voortplanting zal deze eigenschap bij alleen maar een deel van de nakomelingen teruggevonden worden. Om de gewenste eigenschappen te behouden, vinden zaadwinning en veredeling plaats binnen een zeer gespecialiseerde bedrijfstak.

Nu, in onze tijd, waarin de ordening van de levende natuur, de visie op de oorsprong van het leven en het inzicht in de erfelijke eigenschappen onbetwistbaar deel uitmaken van de wetenschap, vindt er een volgende onwenteling van menselijk ingrijpen in de natuur plaats die verder gaat dan het traditionele kruisen en selecteren. Deze omwenteling is vergelijkbaar met die, welke informatie- en communicatietechnologie in de samenleving teweeg brengen. De mogelijkheid die zich nu aandient, het direct ingrijpen in het genoom en te combineren wat van nature niet combineer-baar is, is onderwerp van een maatschappelijke discussie met zeer extreme standpunten.

De pro-argumenten, als het gaat om planten, worden ingegeven door het perspectief van opbrengstvergroting van gewassen en de mogelijkheid om ziekten en plagen op een nieuwe manier te voorkomen en te bestrijden. Dit bezien tegen de achtergrond van een groeiende wereldbevolking. De contra-argumenten zijn gebaseerd op ethische en religieuze overwegingen, op angst, en ook op het besef van het ontbreken van voldoende inzicht in de consequenties en risico’s van een dergelijk ingrijpen. Niet alleen voor de mens in het natuurlijk systeem, maar ook voor sociale en economische systemen.

Brassica

Brassica, cabbage, is one of the the genera in the mustard family, the Brassicaceae. It has been an important agricultural and horticultural crop ever since the antique world. It’s origin is in Europe and Asia. Nowadays it is grown all over the world. Many species of the genus are food for man and animal. Other ones are grown to produce biofuel.

Cabbage is an annual, bi-annual or perennial plant. Annual means that the plant completes it’s lifespan from germ to seed within one growing season. For a bi-annual it takes two years to do the same, forming a rosette in the first year developing into the adult plant in the second.Because the flowers with four petals and are reminiscent of a cross, the family of Brassicaceae is also called Cruciferae, meaning cross-bearing. The colour of the flowers is yellow or white. The flowers are bi-sexual which means that they contain both male and female organs of reproduction, the stamen and carpels.

A model of the relationships within the genus Brassica is commonly known as the triangle of U, named after Nagaharu U. This is the Japanese name of Woo Jang-choon, a Korean botanist who worked in Japan. In 1935 he published his theory on the evolution and the relationships within the genus Brassica. He describes a triangle with on it’s corners Brassica oleracea L., Brassica rapa L. and Brassica nigra L., each with it’s specific genome with respectively 18, 20 and 16 chromosomes. The crossing of each pair of these species are called Brassica napus L., Brassica carinata L. and Brassica carinata A.Br.. They are the genetic combinations of the first three and have respectively 38, 36 and 34 chromosomes.

The genus Brassica counts more than 30 species. One of these, Brassica oleracea L. is the source of much of the cabbage we eat, e.g. red cabbage and Brussels sprouts. The range of forms, colours and tastes within the species Brassica oleracea L. is so wide that within it seven groups can be distinguished.

This diversity developed during the course of millennia by crossing and selection, partly naturally and spontaneously, and for an other part by man. Of these seven groups Brassica oleracea var. capitata L. is the largest.

The name Brassica oleracea var. capitata L. is put together according to the system Linnaeus published in his Philosophia botanica in 1751. Brassica, the traditional Latin word for ‘cabbage’ is the name of the genus; oleracea which means ‘vegetable-like’ is the name of the species. Var. is the abbreviation of the word variety. This taxon, i.e. this distinguishable and named group, is one step lower in the classification than the taxon species. The Latin capitata means ‘with a head’.

The custom to use Latin to write scientific work began around the year 1500 with the recovery of classical antiquity and the rise of humanism. Scientists with a different native tongue could exchange their work by means of this dead language. During the Enlightment, two hundred years later, there is a counter-movement propagating to write in the original language. For Linnaeus’ systematic work however Latin remained the most suitable.

The big differences in colour, form, taste, cultivation, resistance to diseases of the various species and strains of cabbage is amazing when one realizes that all this comes from the same source. When one only looks at the group Brassica oleracea var. capitata L., called by the general name ‘headed cabbage’, one finds hundreds of strains. To this group belong red cabbage, white cabbage, kale and savoy. What connects this group is that selection was aimed at the development of the leaves as the edible parts of the plant. In a second group, Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera DC., the accent is on development of the side-buds of the stem, with Brussels sprouts as the result. In the group Brassica oleracea var. botrytis L. we see undeveloped, crowded, abnormal flower-buds. To this group belongs cauliflower. Kohlrabi, finally, with it’s enlarged stem belongs to the group Brassica oleracea var. gongyloides L..

The variety of form, colour, taste of which we can dispose of now was achieved by human knowledge, ingenuity, patience and economic objectives. The properties of a strain, this special combination of heriditary qualities which was obtained by crossing and selection is not stable. When spontaneously propagating it will dissolve again in the population and will be found back only in a limited number of the offspring. To maintain these qualities this proces of artificial selection has to continue. This is done in a very specialized branch of industry.

Now, in our time, when classification of living nature, vision on the origin of life and understanding of heridity are undisputedly part of science, there is a next revolution of human intervention in nature which goes beyond the classical crossing and selection. The impact of this revolution can be compared with the one which information and communication technology cause in society. The techniques to combine artificially what by nature cannot be combined are subject to a broad discussion with very extreme standpoints.

The pro-arguments in this discussion, when plants are concerned, are inspired by the perspective of a greater productivity of crops and the possibility to prevent and fight diseases and pests. Seen against the background of a growing world population. The contra-arguments are founded on ethical and religious considerations, on fear and on the realization of lack of sufficient understanding of the possible consequences and risks of this intervention. Not only for man in the natural system, but also for social and economic systems.

Carolus Linnaeus 1707 - 1778

Brassica nigra

Brassica carinata Brassica juncea

Brassica oleracea Brassica napus Brassica rapaModel van verwantschappen binnen het geslacht Brassica. Driehoek van U, 1935. Model of relationships within the genus Brassica. Triangle of U, 1935.

De ‘klassieke’ variëteiten van kool. The ‘classical’ varieties of cabbage.

Brassica oleraceae L.

var. viridis boerenkool kroezend blad kale curly leafvar. gemmifera spruiten vergrote stengelknoppen Brussels sprouts enlarged stem budsvar. capitata sluitkool rode, witte en savoye, blad headed cabbage red, white and savoy, leafvar. botrytis bloemkool gemuteerde bloemknoppen cauliflower mutant flowerbudsvar. italica broccoli onrijpe bloemknoppen broccoli unripe flowerbudsvar. gongyloides koolrabi tot knol verdikte stengel kohlrabi tuber-like enlarged stemvar. costata portugese kool blad met dikke, vlezige nerven portuguese cabbage leaf with thick fleshy venation

De meeste zijn wintergroenten, het seizoen is eind maart grotendeels voorbij. Savoyekool is een zomergroente. Most of them are vegetables of wintertime; by the end of march the season is over. Savoy cabbage is a summer vegetable. Enkele ‘moderne’ variëteiten van kool. Some of the ‘modern’ varieties of cabbage.

Brassica alboglabra chinese broccoli stengel, blad, bloem Chinese broccoli stem, leaf, flowerBrassica campestris var. Chinensis chinese kool blad Chinese cabbage leafBrassica pekinensis paksoi stengel, blad paksoi stem, leaf

Bassica napus, koolzaad

Brassica oleraceaRaphanus sativa

R. s. x B. o.

n = 8BB

n = 17BBCC

n = 18AABB

n = 9CC

n = 19AACC

n = 10AA

MILESTONES

MIJLPALEN

LinnaeusM

endelD

arwin

Watson &

Crick

19501750

1850classificatie van levende organismenbinomiale nomenclatuurclassification of living organismsbinomial nomenclature

ontdekking van de struktuur van het dnadiscovery of the structure of the dna

wetten van de erfelijkheidlaws of heredity

evolutietheorietheory of evolution

Linnaeus

Bach

Goethe

Voltaire

Mozart

Haydn

Diderot

Thomas Jefferson

Montesque

Rousseau

Aam Smith

George Washington

David Hume

Newton

Lavoisier

Hegel

Kant

Schiller

1707 - 1778

1685 - 1750

1749 - 1832

1694 - 1778

1756 - 1791

1732 - 1809

1713 - 1784

1743 - 1826

1689 - 1755

1712 - 1778

1723 - 1790

1732 - 1799

1711 - 1776

1643 - 1727

1743 - 1794

1770 - 1831

1724 - 1804

1759 - 1805

TIJDGENOTEN

CONTEMPORARIES

1650

1700

1750

1800

Petrus ArtediBoerhave

Johannes Burman

George Clifford

Hartecam

p

DE NEDERLANDEN

THE NETHERLANDS

Here lies poor Artedi, in foreign land pyx’dNot a man nor a fish, but something betwixt,Not a man, for his life among fishes he pastNot a fish, for he perished by water at last

George Shaw (1751-1813)

George Clifford neemt Linnaeus in dienst. Johannes Burman bemiddelt hierin. Hij is botanicus aan de Hortus in Amsterdam en hoogleraar botanie. George Clifford employs Linnaeus, with the help of Johannes Burman. Burman is professor of botany and conservator of the Horticultural Garden in Amsterdam.

Linnaeus is lijfarts van Clifford en hortulanus van Hartecamp. Met het classificatiesysteem van de Systema Naturae als leidraad maakt hij een inventarisatie en beschrijving van de plantenverzameling van Clifford, de Hortus Cliffortianus. Linnaeus is Clifford’s personal physician and the conservator of the gardens of Hartecamp. On the basis of the Systema Naturae Linnaeus makes an inventory and description of the plant collection, the Hortus Cliffortianus.

Vóór Linnaeus op het toneel verscheen was deze plantenverzameling geordend volgens het systeem van Boerhave, de Index alter plantarum. Before Linnaeus this collection was arranged according to the system of Boerhave, the Index alter plantarum.

Boerhave is arts en botanicus van de Hortus in Leiden, hoogleraar medicijnen, botanie en chemie. Door zijn tijdgenoten en leerlingen wordt hij de ‘praeceptor Europe’ genoemd, leermeester van Europa. Hij kende Clifford en stimuleerde diens interesse in planten. Boerhave is physician and botanist of the horticultural garden in Leiden, professor in medecine, botany and chemistry. He is called ‘praeceptor Europe’, the teacher of Europe, by his contemporaries and students. He knew Clifford and stimulated his interrest in plants.

Het buiten Hartecamp ligt bij Bennebroek aan de trekvaart tussen Haarlem en Leiden. In Linnaeus’ tijd werd het bewoond door George Clifford, koopman en bankier.

The Hartecamp manor is near Bennebroek on the canal between Haarlem and Leiden. In Linnaeus’ time it was inhabited by George Clifford, merchant and banker.

Plattegrond uit ‘Hortus upsaliensis’ van Samuel Nauclér. Plan from

‘Hortus upsaliensis’ by Samuel Nauclér.

Botanische tuin van Uppsala. Botanical garden of Uppsala.