Wan Faber Fung

-

Upload

adhy-tathu-psirius -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

0

Transcript of Wan Faber Fung

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

1/29

Perceived Impact Of Thin Female Models In Advertising:

A Cross-Cultural Examination Of Third Person Perception And Its Impact On Behaviors

Fang Wan

Vanderbilt University

Ronald J. Faber

University of Minnesota

Anthony Fung

Chinese University of Hong Kong

Introduction

Contemporary western culture extols the virtues of slenderness while promoting a fear offat (Dionne, Davis, Fox and Gurevich, 1995). In a 1997Psychology Today Body Image Survey,

eighty-nine percent of the women, and fifty-four percent of the men said they want to loose

weight, and more than sixty percent said they are dissatisfied with their overall appearance--especially their body weight, hips and abdomen (Garner, 1997). Such dissatisfaction may cause

individuals to resort to risky means to control their body weight and appearance. For example, a

national study of women found that a 1 out of 100 females is anorexic and 3 out of 100 are

bulimic (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Other attempts to control body image includesmoking, bingeing and purging, excessive exercise, dieting and surgical procedures. These

practices suggest a worrying picture of young women who are obsessed with their appearance.

Western society has been criticized for its emphasis on a slim physique and negativestereotyping of obese figures. The cultural ideals of thinness has been proposed to cause mass

dissatisfaction with body shape and weight concerns among the female population, whichultimately lead to negative attitudes toward eating, a preoccupation with weight and dieting and a

high prevalence of eating disorders (Tiggeman & Rothblum, 1988; Powell & Kahn, 1995).

However, it is unclear if this phenomenon is unique to a Western cultural context and to Westernwomen only. Do young women in Non-Western culture manifest similar patterns of weight

concerns and weight-controlling behaviors? What role do idealized images in advertising play in

the perception of body image and image-enhancement behaviors?

This paper attempts to investigate the role of thin female models in advertising in the

body image perception and image-enhancement behaviors in a cross-cultural context. It beginswith a literature review of cross-cultural studies of body image perceptions and behaviors. Itthen employs a relatively new theoretical perspective to attempt to account for a less direct

impact of the mass media on behavior. This is referred to as the third person effect . this model

will be explained and discussed in both a North American and East Asian context. Lastly, itinvestigates the relationship between the third person perception of the impact of thin female

models and image-enhancement behaviors in a cross-cultural context.

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

2/29

Cross cultural research on body image perceptions and eating attitudes:

Cross-culturalresearch on eating disorder and body image perception has been limited,the majority of this literature has dealt with whether Western norms and values of female

thinness influenced non-Western womens, (specifically Asian womens) eating patterns and

perceptions of their body image (e.g., Dolan, 1991; Ahmad, Waller & Verduyn, 1994; McCourt& Waller, 1995; Akan & Grilo, 1995; Rosenthal & Feldman, 1990). Research in this area has

focused on either women immigrated into a Western culture (e.g., Furham & Alibhai, 1983;

Lake, Staiger & Glowinski, 2000), or women exposed to Western values in their home country(Mumford, Whitehouse & Choudry, 1992).

Studies have found an increase in the incidence of eating disorders among non-Western

women entering Western society (Dolan, 1991). Two opposing explanations have been offeredfor these findings. The first attributes an increase in maladaptive eating patterns to a culture

clash experienced by individuals who migrate to a new country. This leads to pressure to adapt

to a new culture which then causes problematic behavior. Research evidence supporting this

view has shown that more traditional females (i.e., those having a stronger identity with theircountry of birth) are at a higher risk of developing eating disorders due to the difficulties

experienced in growing up with conflicting cultural values (Ahmad, Waller & Verduyn, 1994;McCourt & Waller, 1995). A recent study by Lake and colleagues (Lake, Staiger & Glowinski,

2000) compared Australian-born and Hong Kong-born University students residing in Australia

They found that Hong Kong-born subjects who demonstrated a higher level of Chinese identity(more traditional) were more affected by Western attitudes toward eating and body image than

those who were influenced by Western values.

Cultural assimilation provides an alternative view for explaining the development ofeating disorders among non-Western women. This theory suggests that non-Western women

demonstrate an increasing pattern of eating disorders when they move to a Western culture

because they need to assimilate the host society norms and values. This includes assimilating toa new image of the ideal female body shape. Some literature has indicated non-Western women

who have a higher level of assimilation of Western norms and values are at a higher risk of

developing eating disorders (Akan & Grilo, 1995).

Body image among Asian women

Much of the existing literature on the body image of Asian respondents has examined

people in Japan (Endo, 1992; Kowner & Ogawa, 1993; Shibata & Nobechi, 1991), or Asiansliving in Europe or North American (e.g., Arkoff & Weaver, 1966; Furnham & Baguma, 1994;

Hill & Bhati, 1995; Marsella, Shizuru, Brennan, & Kameoka, 1981). More recently, there is a

growing number of studies examining Chinese men and women in Hong Kong (Lee et al, 1997;Davis & Katzman, 1997; 1998; 1999). Davis & Katzman (1997) have argued that data on

women from modernizing cultures in Asia such as Hong Kong is important for cross-cultural

comparisons since these cultures are experiencing rapid social change in the face of an influx ofWestern values and ideals.

When compared to European American male and female students, Chinese-born

undergraduates in Hong Kong demonstrate a similiar pattern of dissatisfaction with various body

2

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

3/29

parts (Lee et al., 1993). Lee et al (1993) argued that young Chinese women share a similar ideal

of slimness as their Western counterparts, although dieting and eating disorders remain rare. In a

series of studies, Davis & Katzman found that Chinese women in HK held more negative viewsof themselves, their bodies and their mood when compared to Chinese women in the United

States (Davis & Katzman, 1997; 1998). They also found Chinese subjects in Hong Kong

reported significantly more body and weight dissatisfaction, lower self-esteem, higherdepression, more dieting and less exercising as compared to their counterparts in the United

States (Davis & Katzman, 1998). Davis & Katzman (1998) concluded that Asian students

mirrored gender patterns previously reported in Caucasian samples with the respect to therelation of body image, self-esteem and mood. Interestingly, researchers (Lee et al, 1996;

Katzman, 1996) found that even though the current weight of Chinese women is below the ideals

of European and American women, they were still under pressure to diet. Again, the prevalence

of body image and weight concerns in East Asia was ascribed to the increasing modernizationand exposure to European and American ideals which leads to the devaluation of the once-

sought-after fat body in traditional Asian culture (Buhrich, 1981).

The limited research evidence has shown that Chinese women in HK demonstrate asimilar pattern of body image worries and concerns compared to their counterparts in US (e.g.,

Lee et al, 1993). This study serves to further explore this issue. Therefore, the first goal of thisstudy is to determine if there are differences in body image perception and image-related

behaviors such as dieting, exercising and the likelihood of plastic surgery between young women

in the U.S. and Hong Kong.

RQ1: Do young women in Hong Kong and United States demonstrate the same level

of body image concerns and disturbance and the same intensity of engaging in

image-related behaviors?

Third Person Effect: A Theoretical Framework

Researchers have claimed that the ubiquitous ultra-thin ideal female images presented asthe norm in the media may be responsible for perpetuating highly unrealistic ideals in women

(e.g., Fallon, 1990; Harrison, 2000). These authors assume that this leads to the development of

unhealthy behaviors. In contrast, the third-person effect provides a very different explanation ofhow media images may influence such actions.

Postulated by Davison in 1983, the third-person effect is the perception that persuasive

communication will exert a stronger impact on others than on the self. As Davison (1983, p.3)

noted, individuals exposed to a mediated message typically believe that the message will nothave its greatest effect on me (the first person), or you (the second person), but on them

third persons. The robustness of the third person effect has been demonstrated across a broad

range of media using survey and experimental methods (e.g., Cohen et al., 1988; Gunther, 1991,1992, 1995; McLeod et al., 1997; Perloff, 1989; Salwen & Driscoll, 1997).

The third-person effect framework postulates an intermediate process of media impact.

Instead of assuming a direct link between media exposure and attitudes/behaviors, third-personeffect lays out a two-step persuasion process. According to this framework, media exerts

influence not through ones own interaction with media message, but through the projection of

how others may respond to those messages. To some extent, the estimation and projection of

others reactions to media messages is a constituent part of perceived social norm of media

3

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

4/29

persuasiveness (Wan, 2001). Thus people consistently demonstrate a perceptual gap between

media susceptibility of themselves and others. It is the perceived belief that the media exert an

influence on others that drives individuals to take some action (Wan, 2001).

Research on the third-person effect has found that it only exists in certain situations. When

a message is perceived negatively, or when being persuaded by it would be generally regarded asunintelligent, people estimate more that others will be more influenced than they will. However,

when a message is considered positive, people attribute themselves as equally or more effected

since they are smart enough to recognize its value (Cohen and Davis 1991; Gunther andThorson 1992).

Other perceptions or attitudes regarding the message also influence the size and direction

of the perceptual gap. Some studies have found that there is a greater disparity betweenperceived effects on the self and others when the source of the message is judged to be

negatively biased (Cohen et al. 1988; Gunther 1991) or when the audience attributes persuasive

intent to the communicator (Gunther and Mundy 1993). Other research shows that those who

consider an issue important (Matera and Salwen 1996), perceive themselves as experts (Lasorsa1989), or are highly ego-involved in the message (Perloff 1989) tend to perceive that others will

be more affected by message content.

Embedded in the third person effect framework are additional intricacies in the

relationships between self and others which can influence the perceptual gap. Research findingshave shown that different conceptualizations and definitions of others influence the direction

and magnitude of the third person effect. When others are defined in terms of geographical

closeness to the first person, the discrepancy between perceived media effects on others and the

self are not as large as when others are more distant (Cohen et al., 1988; Cohen and Davis, 1991;Gunther, 1991; Duck & Mulin, 1995). For example, Cohen et al. (1988) found that while

subjects perceived that news stories would exert a greater impact on other Stanford students

than on themselves, this difference was even greater when the self was compared with otherCalifornians and still greater when compared to the public at large. When others are

defined in terms of perceived similarity or social distance (e.g., Brosius & Engel, 1996; Eveland

et al., 1999), individuals again tend to see less difference between themselves and similar groups(closer others) than with dissimilar others (more distant groups) (Eveland et al., 1999). For

example, people tended to infer greater negative media effects on groups less similar to

themselves (average others) than with more similar groups such as friends (Brosius and Engel,

1996).

Differences in third-person effects can also be defined in terms of gender (Duck, 1997;

Wan & Wells, 2001). In a study of perceived effect of commercial advertising, Duck (1997)found that both male and female respondents perceive themselves as less influenced by

commercial advertising than othersmen in general and women in general. However, both

male and female respondents perceived womenthe subordinate group in social stereotypeasmore vulnerable than men were to the effects of commercial advertising (Duck, 1997). Wan &

Wells (2001) also defined others in terms of gender identity. Consistent with Ducks finding,

Wan & Wells (2001) found that both female and male respondents perceived ads with sexual

female images to have less impact on themselves than others. However, they found an

4

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

5/29

interesting effect of similarity of the other. A gender similar group (for male respondents, men

in general; for female respondents, women in general) was perceived to be less influenced by

sexual image ads than gender outgroup (for male respondents, women in general; for femalerespondents, men in general).

Part of the goals of this study were to examine how people would perceive the impact ofthin female models on different others. Both gender identity and social distance were used to

define others. Specifically, five different others were examined: a) female friends; b)

male friends; c) most women; d) most men; and e) my current/potential romanticpartner. These sets of others are assumed to be important agents in a persons social

interactions. They range from being close (romantic partner; female friends; male friends) to

distant (most men; most women) and from being same gender in-group members (female

friends; most women) to outgroup members (male friends, most men).

To generate specific hypotheses regarding third person effects, we need to consider the

social desirability of the medias influence. When the media content is seen as having socially

undesirable outcomes others are perceived as more vulnerable to this effect than ones-self (thirdperson effect). However, when the media content is judged to be positive, either no difference,

or a belief that the impact will be greater on ones-self than on others (the first person effect) islikely.

Social critics, media educators, and others have vehemently criticized media andadvertising for their unrealistic portrayal of female images and the negative impact those

idealized images have on young people (e.g., lowered self-esteem; eating disorder likelihood;

excessive exercising). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that susceptibility to idealized

images in advertising will be viewed as having a negative connation and be seen as sociallyundesirable. Hence, people should deny that they themselves are susceptible while being more

likely to assume that thin female models portrayed in advertising influence others. We would

then expect a classic third person effect:

H1a: Thin female models in advertising are perceived to have less impact on self

than on others (third person effect).

However, as noted earlier, the magnitude of the third person effect is moderated by social

distance. If others are more distant, the perceived impact of thin female models on them should

increase. Since, people have limited information about distant others, they adhere more to socialstereotypes to estimate the impact. In this situation, social stereotypes seem to be that thin

female models in advertising set the standards of how women should look. So, when estimating

the impact of the idealized images on these distant others, people would retrieve those socialstereotypes and infer that others are more vulnerable to the idealized images than themselves.

However, when others are relatively closer to one self, for example, friends or romantic

partner, people would attribute more similarity in abilities and thoughts to them. Therefore, wewould expect that:

H1b: The gap between perceived impact of thin female models in advertising on self

and others is smaller when others are close to self (i.e., female friends; male

5

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

6/29

friends; romantic partner) than when others are more distant to self (i.e., most

men; most women).

In addition, as discussed earlier, gender identity can also influences the third person

perception. Female respondents should think that men are more influenced by thin female

models than they themselves or other women are (Wan & Wells, 2001). This is because ingroupmembers are perceived to be more similar to others, and therefore would be similarly influenced

by media messages (Duck, Hogg & Terry, 2000). Therefore, we would expect that:

H1c: The gap between the perceived impact of thin female models in advertising on

self and others is smaller when others belong to ones gender ingroup (i.e., female

friends, most women) than when others belong to gender outgroup (romantic

partner, male friends, most men).

A cross-cultural inquiry into the third person effect

In a comprehensive review of third person effect research, Perloff (1999) summarizedvarious factors influencing the third person effect. Among these factors are message desirability,

social distance of others, media use orientations, knowledge, issue importance, self-esteem and

ego-involvement. However, he pointed out that there is a need to further examine possiblecontextual variations in the third person effect. One of the contextual factors he mentioned is

cultural context.

To date, there are no published study examining a cross-cultural difference in the third

person effect. Cross-cultural research on this phenomenon is important to determine its

universality.

Perloff (1999) speculated that third-person effects may be less pronounced in Asian

cultures. He based this belief on the fact that Eastern cultures emphasize the interrelatedness of

people with others in their social environment, while in Western culture, the focus is more on theuniqueness and autonomy of individuals. Literature in cultural psychology, especially in the area

of different self-construal in Eastern versus Western culture, support Perloff s proposition.

In general, the key differences between Asian and Western culture is the definition of

selfhood or self construal (Markus& Kitayama, 1991; Kitayama, Markus and Kurokawa, 1994;

Kim & Markus, 1999). Markus and Kitayama (1991) defined the independent construal of selfas characterized by a bounded and autonomous sense of self that is relatively distinct from others

and the environment. This view is best exemplified by North American and Western European

cultures. In these cultures, individuals strive to assert their individuality and uniqueness and

stress their separateness from the social world.

In contrast, the interdependent construal of self emphasizes the interrelatedness of the

individual to others and to the environment (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). It is only within thecontextual fabric of social relationships, roles, and duties that the self has meaning. This

construal of self is most representative of Asian cultures. Miller (1993) employed another

concept co-subjectivityto describe the interdependent self-construal in Asian culture.

6

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

7/29

According to Miller (1993), co-subjectivity in Japan is the formation of subjects through

identification with a group or community (p.482).

In a culture characteristic of interdependent self-construal, attending to others, fitting in,

and harmonious relations are valued and socially rewarded (Markus and Kitayama, 1991).

Therefore, we would expect that people from such a culture would tend to focus on the similaritybetween self and others. In contrast, in a culture characteristic of independent construal of self,

inner attributes of a person such as self-sufficiency, autonomy and actualizations of ones goals,

desires and needs are valued. Therefore, when engaging in a social comparison process, wewould expect that people from this type of culture will emphasize the dissimilarity between self

and others.

The above proposition gains some support from a cross-cultural study on unrealisticoptimism (Heine & Lehman, 1995). They found that people from cultures representative of an

interdependent construal of self do not engage in self-enhancement to the same extent as people

from cultures characteristic of an independent self. They believe that self-enhancing biases serve

to buttress ones self-assessments to help achieve a norm valued by an independent culture.However, in an interdependent culture, people realize their cultural ideals by self-effacement.

This minimizes their distinguishing, and potentially alienating, features and allows them tomaximize their sense of belongingness (Heine & Lehman, 1995).

Additional research findings with American subjects suggest that the self is judged to bemore dissimilar to other than other are to the self (Kitayama, Markus, Tummala, Kurokawa, &

Kato, 1990; Holyoak & Gordon, 1983; Srull & Gaelick, 1983). This pattern, however, is

reversed for Eastern subjects, who judged the self somewhat more similar to others than the other

is to the self. It appears that, for more interdependent subjects, knowledge about others isrelatively more elaborated and distinctive than knowledge about the self.

Applying this to third person effect leads to an expectation that there will be culturaldifferences. In Asian cultures, it is assumed people will focus on their belongingness to and

interrelatedness with others, and will therefore yield similar estimation of media vulnerability for

themselves and others. However, for Westerners, differences between the self and others will beintensified to enhance ones superiority over others. This will lead to a larger difference in

perception of the medias influence on self versus others. Thus, we would expect that:

H2: The gap between perceived impact of thin female models in advertising on self

and others is larger in an independent culture (e.g., United States) than in an

interdependent culture (e.g., Hong Kong)

Behavioral consequences of third Person Effect:

A considerable amount of research on the third person effect has demonstrated that

perceptual gaps exist for a wide range of messages and social contexts. However, explorationsexamining behavioral components of the third person effect have been meet with far more

limited success. By far, the most commonly documented behavioral impact of a gap in third-

person perceptions is a greater willingness to support censorship of content that is deemed

undesirable (Perloff, 1999).

7

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

8/29

Researchers have found that the difference between the perceived impact on others and

on ones-self is related to peoples willingness to advocate censoring media materials such as

pornography (Gunther, 1995; Rojas, Shah, & Faber, 1996), violence on TV (Gunther & Hwa,1996), advertising for controversial products (Shah, Faber, & Young, 1999; Youn, Faber, Shah,

2000) and violent and misogynic rap lyrics (McLeod et al., 1997). However, in some cases

regarding news and political communications, a behavioral effect has not been found. Forexample, third person perceptions did not predict willingness to limit press coverage of the

O.J.Simpson trial (Salwen & Driscoll, 1997). Similarly, this gap failed to significantly predict

support for an independent commission to regulate political communications (Rucinski &Salmon, 1990), or opposition to printing a Holocaust-denial advertisement (Price, Hung &

Tewksbury, 1997).

Testing whether third person perceptions predict willingness to censor media content is atbest only a small subset of the possible behavioral components of the third person effect. Yet

little evidence for other aspects of this hypothesis have previously been found.

Recently, Wan (2001) proposed that the belief that the perceived impact of idealizedimages in advertising on others can influence an individuals behaviors. These behaviors may

include dieting, exercising and the likelihood of plastic surgery. Integrating social influencetheory with the third person effect, she suggested that the third person perception be

conceptualized as the perceived social norm of media persuasiveness (Wan, 2001). That is, if

media influence is desirable for a social group, and an individual identifies with that group,he/she would comply to the group norms by acting in accordance with the media messages. An

individuals conformity to perceived norm of media influence results either from their

internalization of group norms and values, or from a simple self-presentation motive-- to project

an appropriate image in order to fit in.

It should be noted that a different psychological mechanism is predicted here than is atwork in censorship effects. In the case of the third person perception and willingness to censor, a

paternalistic motivation is perceived to be the driving force. People believe others will be

harmed by media messages and need to be protected from the effect of those messages.

However, here it is believed that the third person perception and behavior linkage is driven by adesire to conform to group norms that are thought to be shaped by media presentations. This

study attempts to empirically test this component of the third person model. Here, if ones peers

(male and female friends), romantic partners and larger social group (most men or most women)are perceived to be influenced by thin female models in advertising, then acceptance by these

groups will depend on adhering to these norms. Thus, even if advertising images do not directly

influence ones own perceptions, they can still create a need for behavioral change. Hence, it ispredicted that:

H3: The gap between perceived impact of thin female models in advertising on

self and others will predict image-related behaviors.

The final goal of this study is to test the third person model of behavioral impact in a

cross-cultural context. Since the role of others is defined differently for interdependent andindependent construal of self, there could be a cultural difference in terms of the level of social

8

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

9/29

conformity. According to Markus & Kitayama (1999), others in independent cultures serve

primarily as standards of reflected appraisal, or as sources that can verify and affirm the inner

core of the self. However, others in an interdependent culture are assigned more importance,carry more width, and are relatively more focal in directing ones behavior. To maintain a

connection to others, interdependent people are constantly aware of others needs, desires and

goals. Additionally, they are more likely to internalize the goals of others and make them theirown. Furthermore, in an interdependent culture, following norms is a core cultural goal that

fosters group harmony (Hsu, 1948). As Markus & Kitayama (1991) pointed out, in an

interdependent culture, there is a need as well as a strong normative demand to know andunderstand others thinking, feeling and action in the context of ones relationships to them.

Compared to people in an independent culture, the most important element of self-

construal in interdependent societies is the self-in-relation-to-others element. This couldintensify the pressure to conform to group norms and strengthen the relationship between

perceived social norm and ones own behavior. Therefore, compared to people in an

independent culture, people in interdependent cultures tend to demonstrate a higher level of

social conformity (Kim & Markus, 1999).

It is, therefore, theoretically reasonable to expect that the relationship between thirdperson perceptions and image enhancement behaviors will be stronger in an interdependent

culture than in an independent culture. However, the value of prior research in this area is

limited by the fact it has only examined public behavior. Most cross-cultural research on socialconformity has addressed ones expressed opinion in front of a group after the group opinion has

been presented (e.g., Huang & Harris, 1973; Meade & Barnard, 1973; Bond & Smith, 1996).

This is a very public indication of behavior. However, the behaviors examined in this study are

private in nature and lack an overt confrontation with group norms. Thus this hypothesis mustbe considered very tentative and is, instead, presented in the form of a research question.

RQ2: Is the relationship between the third person perceptions of thin female models

and image-related behaviors stronger in an interdependent culture than in an

independent culture?

Methodology:

Sample

Altogether, 505 female respondents participated in the study. Chinese respondents came

from an introductory communications class at a major university in Hong Kong. There were atotal of 122 Chinese women who participated. The questionnaires distributed in Hong Kong

were written in English, given the high English proficiency of Hong Kong students. In fact, at

many universities in Hong Kong, English is the required language for instruction. Respondentsfrom Hong Kong sample were all between the ages of 19 to 28.

The U.S. data were collected by the students enrolled in an advertising course at a

Midwest university as partial fulfillment of a course project. Members of the class whoparticipated in this project each interviewed 10 women between the ages of 18 to 30. A total of

383 U.S. women were interviewed.

9

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

10/29

Sample Comparison:

The mean age of the U.S. respondents was 21.6 , while the average age of the Hong Kong

respondents was 20.6. The average height of the Hong Kong women was 159.8m or 5 feet 3inches. Their average weight was 49.1 mg or 108 lbs. For the U.S. respondents, the mean height

was 167.8m or 5 feet 6 inches, and their average weight was 62.3 mg or 137.2 lbs. Thus, the

U.S. women were both heavier (F(1,483)=183.9, p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

11/29

Outcome measures. Three kinds of potential outcome measures were assessed in the

study. Two of these were behavioral measures (dieting and exercising) and one was a behavioral

intent measure (likelihood of having plastic surgery). Dieting was measured by a single item:How frequently have you been on a diet? The respondents were asked to choose from the

response: never, rarely, sometimes, often, and always.

Exercising was measured by two items. The respondents were asked to indicate how

frequently they engage in exercising. This question also used the response categories of

never, rarely, sometimes, often and always. The second exercise question askedrespondent on average, how many hours per week do you spend exercising? They were given

the following eight response categories to choose from: less than 1 hour per week, at least 1

hour, but less than 2 hours, at least 2 hours, but less than 3 hours, at least 3 hours, but less

than 4 hours, at least 4 hours, but less than 5 hours or more per week. We assigned the valuesranging from 1 to 8 to the response categories in this measure. A reliability test yielded an alpha

of .79 for the two exercise items. Based on this, we standardized each of these scores and

summed the standardized scores. Thus scores could range from 0 to 2. Actual scores on this

exercise scale ranged from .13 to 1.80 (standard deviation=.44).

The third behavior variable was the likelihood of performing plastic surgery. Abehavioral intention variable was used here since actual prior behavior may have been limited by

financial or other considerations. This outcome variable was assessed with two items: If I did

not like the way some feature of my face looked, I would consider having plastic surgery tochange it, and if I did not like the way some feature of my body looked, I would consider

having plastic surgery to change it. The respondents were asked to use a five-point scale with 1

indicating strongly disagree and 5 strongly agree. These two items were then averaged to

create a final index of willingness to have plastic surgery.

Body Image Disturbance. Body image disturbance was measured by five items selected

from Cooper, Taylor, & Fairburn (1987) s seventeen-item index of Body ImageDisturbance. The five chosen items were: Have you been afraid that you might become fat or

fatter? Have you limited what you eat to stay thin? Have you felt depressed about your

shape? Have you avoided wearing clothes that make you particularly aware of the shape ofyour body? Have you been particularly self-conscious about your shape when in the company

of other people? We chose the five items because they formed the subscale of negative body

image.

The respondents were asked to respond to these questions by choosing one of the

response categories: never, rarely, sometimes, often and always. Exploratory factor

analysis of the five items with Principal Component Analysis and Varimax Extraction methodyielded a single factor solution, explaining 62.7% of the total variance of the underlying

construct. The five items had reasonable reliability (alpha=.85) and were therefore averaged to

create a body image disturbance index.

Results

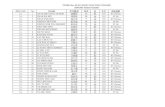

To answer the first research question, we conducted a series of ANOVA analyses with

culture as a fixed between-subject factor. The results are shown in Table 1.

11

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

12/29

(Insert Table 1. about here)

Cross-cultural differences in five dependent variables were examined. These were body

image disturbance, dieting, exercising every day, exercising hours per week and likelihood ofhaving plastic surgery. The results in Table 1 demonstrate significant main effects of culture for

three of the five variables examined. Specifically, compared to HK respondents, the U.S.

respondents reported a higher frequency of exercising everyday than HK sample (F (1, 504)=26.97,eta-squared=.05, p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

13/29

both themselves and others similarly. However, when others are phrased in a more socially

distant way (such as most men or women), respondents will perceive that thin female models in

advertising will influence others to a greater extent than themselves.

Hypothesis 1c

Hypothesis 1c stated that there would be a significantly smaller gap when the other wasones gender in-group than when the other was composed of gender out-group members. To

examine this hypothesis, two variables were created. Perceived impact of thin female models on

gender out-group (male others) was created by averaging three variables--perceived impact onmale friends, most men and romantic partner). Taking the average of perceived impact on

female friends and most women created the impact of advertising models on gender in-group.

Again, a repeated measure MANOVA was computed with one within-subject factor (social

distance of others; 2 levels: close versus distant others) and one between-subject factor (HKversus US) to examine the impact of gender identity of others and culture on the third person

gap. The results are shown in Table 4.

(Insert Table 4 here)

First, within each culture, class third person effect exists when others are women. Thenegative and significant gaps between perceived impact on self and on female others suggested

that the respondents from both HK and US agreed that the thin female models in advertising

would affect other women to a greater extent than themselves. However, when others are men,first person effect emerges for US women and HK women demonstrated no difference between

perceived impact on me and male others.

Furthermore, MANOVA analysis yielded a significant main effect of gender identity onthe third person gap (F(1,489)=417.29, Eta-squared=.46, p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

14/29

A contrast between distant and close others in terms of a third person gap is more

prominent in the U.S. sample than among HK respondents. This is indicated by the significant

interaction effect of culture and social distance of others on third person gap (F(1,489)=6.34, Eta-squared=.013, p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

15/29

partner significantly predict dieting behavior for US sample. Surprisingly, the direction of the

gaps for these others was different. The more thin female models were perceived to influence

ones-self as compared to most women, the more the respondents would diet (unstandardizedcoefficient=.21, p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

16/29

However, it is important to note that the results here represent just a single point in time.

They cannot determine the degree to which these cultures may be stable or changing. The

findings show that approximately three-fourths of the women in both cultures desire to loseweight. Thus, it may be that in a few more years, similar percentages from both countries will

endorse more extreme methods to achieve idealized looks.

This study also attempted to examine notions regarding the third person effect in the

context of perceived impact of thin female models in ads. U.S. women perceived both female

friends and most women to be influenced by media images to a greater extent than did Chinesewomen. However, the perceived impact of media images on self did not vary across these two

cultural groups. Thus, the difference in the two cultures is manifested only in expectations of the

effect on other women. This may be due to difference in interpersonal communication or in the

cultural norms and beliefs operating in each society.

In both countries, a third person effect gap existed when comparisons were made between

self and female friends, most women and most men. Surprisingly, a reverse gap appeared for

both groups when comparisons were made with romantic partner. A reverse gap was also foundfor the U.S. sample when comparisons were made with the impact on male friends. This reverse

gap for romantic partner and male friends was surprising, especially given that it occurred inboth cultures. While the reason for it is unclear, a couple of possibilities exist. It is possible that

the males these women know dont appear to pay attention to female models in ads. They dont

read fashion magazines or perhaps simple choose not to make comments about the appearance ofthese models. Alternatively, this may represent a self-protection belief system among women in

both cultures. If they believe that the males they actually know (and care about) arent being

influenced by these images, then they wont be as worried about being judged harshly by these

friends. Future research exploring what leads to these beliefs about the impact of media imageson male friends and romantic partners would be valuable.

The path analysis examining the linkage between the third person perception and imagerelated behaviors yielded interesting findings. For both the HK and U.S. women, behaviors

related to physical appearance were partly triggered by the perceptions that their romantic

partners are more susceptible to the influence of thin female models in ads than the respondentherself. This difference significantly predicted dieting among the U.S. respondents and

approached significance in predicting exercising among the HK women. For both cultural

groups, the gap in perceived influence between self and romantic partner significantly predicted

willingness to consider plastic surgery.

These findings suggest that the third-person effect can lead to behavioral outcomes

beyond just censoring media messages. This provides important additional support forDavisons original claims regarding this theory. However, the results here suggest that

behavioral effects are highly dependent on who the other is. Interestingly, in both cultures,

romantic partner was seen as the other least influenced by advertising images. The perceivedimpact of seeing thin models was considered to be less for ones romantic partner than for the

respondents themselves. However, the more ones romantic partner was seen as being

influenced relative to ones-self, the more women engaged in behaviors to try to achieve an

idealized look. This suggests that behavior is at least partially affected by an indirect influence

16

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

17/29

mediated by the belief that advertising affects ones romantic partner. Thus, the perceptions of

media influence on different others are not equally important in influencing ones own

behavior. Instead, perceived beliefs about others only exert influence when one highly identifieswith or cares about the opinions of certain others (as in this context with romantic partners).

While some differences existed, the findings here were remarkably consistent acrosscultural groups. Given previous research, this may be somewhat surprising. The lack of

cultural difference could be due to the fact that we are examining private behaviors. In contrast

to public behavior (such as express ones opinion publicly), private behaviors are less subject tonormative pressure, which may be true regardless of cultural contexts. An alternative

explanation could be a ceiling effect. The cultural ideal of female thinness and physical

attractiveness have long been valued in Western society and internalized by Western women.

When it comes to behaviors such as dieting, exercising and performing plastic surgery, women inWestern culture have already been socialized to accept a willingness to engage in these behaviors

in order to look good. The findings here may be due to the fact that Hong Kong women are

catching up on these attitudes.

The findings suggest that the use of the third-person effect theory to explain reactions to

the media and their impact on behavior is applicable across cultures, at least in this context.Future studies are needed to see if it also holds up across other forms of consumptions behaviors

and in a greater variety of cultural settings. Nonetheless, as media becomes more universal, it

does suggest that beliefs and perceptions regarding how the media affects others may be animportant determinant in how people will act. The findings here indicate that perceived effects

on some types of others matter more to respondents. Future cross-cultural applications of the

third person effect should attempt to determine if there are any cultural differences on who the

important others are in various contexts.

17

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

18/29

Reference:

Ahmad, S., Waller, G., and Verduyn, C. (1994). Eating attitudes among Asian schoolgirls: Therole of perceived parental control. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 15, 91-97.

Akan, G.E.& Grilo, C.M. (1995). Sociocultural influences on eating attitudes and behaviors,body image and psychological functioning: A comparison of African-American, Asian-American

and Caucasian college women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 18, 181-187.

Arkoff, A., & Weaver, H. (1996). Body image and body dissatisfaction in Japanese-Americans.

Journal of Social Psychology, 68, 323-330.

Bond,R., & Smith, P.B.(1996). Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Aschs(1952b, 1956) line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 111-137.

Brosius, H. B. & Engel. E (1996). The causes of third-person effects: unrealistic optimism,

impersonal impact, or generalized negative attitudes towards media influence?International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 8, 142-161.

Buhrich, N. (1981). Frequency and presentation of anorexia in Malaysia, Australian and New

Zealand,Journal of Psychiatry, 115, 153-155.

Cohen, J., Mutz, D., Price, V., & Gunther, A. (1988). Perceived impact of defamation: An

experiment on third-person effects. Public Opinion Quarterly, 52, 161-173.

Cohen, J & Davis, R.G. (1991). Third-person effects and the differential impact in negativepolitical advertising. Journalism Quarterly, 68, 680-688.

Cooper, P., Taylor, M., Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. (1987). The development and validation ofthe body shape questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6, 485-494.

Davis, Cindy & Katzman, Melaine (1999). Perfection as acculturation: Psychological correlatesof eating problems in Chinese male and female students living in the United States.

International Journal of Eating Disorder, 25, 65-70.

Davis, Cindy & Katzman, Melaine (1997). Charting new territory: Body esteem, weightsatisfaction, depression, and self-esteem among Chinese males and females in Hong

Kong. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 36, 449-459.

Davis, Cindy & Katzman, Melaine (1996). Chinese men and women in the United States and

Hong Kong: Body and self-esteem rating as a prelude to dieting and exercise.

International Journal of Eating Disorder, 23, 99-102.

Davis, C.& Katzman, M.(1998). Chinese men and women in the USA and Hong Kong: Body

and self-esteem ratings as a prelude to dieting and exercise. International Journal of

Eating Disorders,25, 99-102.

18

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

19/29

Davison, W.P.(1983). The third-person effect in communication. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47,

1-15.

Dionne, M., Davis, C., Fox, J., & Gurevich, M. (1995). Feminist ideology as a predictor of body

dissatisfaction in women. Sex Roles, 33:277-287.

Dolan, B. (1991). Cross-cultural aspects of anorexia nervosa and bulimia: A review.

International Journal of Eating Disorders, 10, 67-78.

Duck, J.M. (1997). Gender identity and the perceived impact of commercial advertising.

Working paper.

Duck, J. M., Hogg, M.A. and Terry, D.J. (2000). The perceived impact of persuasive messages

on us and them. In Terry, D.J. & Hogg, M.A (Eds.) Attitudes, Behaviors and Social

Context: The Role of Norms and Group Membership. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum

AssociatesEndo, Y. (1992). Negative ideal self as a standard of self-esteem. JapaneseJournal of Psychology, 63, 214-217.

Eveland Jr., Amy I. Nathanson, Benjamin H. Detenber, Douglas M. McLeod.(1999). Rethinking

the social distance corollary: perceived likelihood of exposure and the third-person

perception, Communication Research, 26, 275-279.

Fallon, A. (1990). Culture in the mirror: Sociocultural determinants of body image. In T.F.Cash

& T. Pruzinsky (Eds.),Body Image, Development and Change (pp.80-109). New York:

Guilford Press.Furnham, A., and Alibhai, N. (1983). Cross-cultural differences in the perception of female

body shape. Psychological Medicine, 13, 829-837.

Garner, D. M (1997). The 1997 Body Image Survey Results. Psychological Today, 30(1),33-

84.

Gunther, A.G. (1995). Overrating the X-rating: The third-person perception and support for

censorship of ponography. Journal of Communication, 45, 27-37.

Gunther, A.G. (1991). What we think others think: courses and consequences in the third-personeffect. Communication Research, 18, 355-372.

Gunther, A. G. & Thorson, E. (1992). Perceived persuasive effects of product commercials andpublic service announcements: Third-person effects in new domains. Communication

Rsearch,19, 574-596.

Gunther, A.G. & Mundy, P. (1993)Biased optimism and the third-person effect. Journalism

Quarterly, 70, 58-67.

Gunther, A.G. & Hwa, A.P. (1996). Public perceptions of television influence and opinions

19

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

20/29

about censorship in Singapore. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 8,

248-265.

Harrison, Kristen (2000). The body electric: Thin-ideal media and eating disorders in

adolescents. Journal of Communication, 51 (2), 119-143.

Heine, Steven J. & Lehman, Darrin R. (1995). Cultural variation in unrealistic optimism: Does

the West feel more invulnerable than the East? Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 68, 595-607.Hill, A.J. and Bhati, K. (1995). Body shape perception and dieting in preadolescent British

Asian girls: Links with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 17,

175-183.

Hsu, F.L.K. (1948). Under the Ancestors Shadow: Chinese Culture and Personality. New

York: Columbia University.

Huang, L.C., & Harris, M.B.(1973). Conformity in Chinese and Americans: A field experiment.

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 4, 427-434.

Katzman, M. (1996). Asia on my mind: Are eating disorders a problem in Hong Kong? Eating

Disorders: Journal of Treatment and Prevention, 3, 379-380.

Kim, Heejung & Markus, Hazel R. (1999). Deviance or uniqueness, harmony or conformity: A

cultural analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 785-800.

Kim, Heejung & Markus, Hazel R. (1999). Deviance or uniqueness, harmony or conformity: A

cultural analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 785-800.

Kitayama, S., Markus, H.R., & Kurokawa, M. (1994). Cultural views of self and emotionalexperience: Does the nature of good feelings dependent on culture? Unpublished

Manuscript, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan.

Kowner, R., and Ogawa, T. (1993). The contrast effect of physical attractiveness in Japan,

Journal of Psychology, 127, 51-64.

Lake, Amelia J. , Staiger, Petra K. & Glowinski, Huguette (2000). Effect of western culture on

womens attitudes to eating and perceptions of body shape. International Journal of

Eating Disorder, 27, 83-89.

Lasorsa, D. L. (1992). Policymakers and the Third-Person Effect, In J. D. Kennamer (Ed.),

Public Opinion, The Press, and the Public Policy, New York, Praeger, 163-175.

Lee, S. (1996). Reconsidering the status of anorexia nervosa as a western cultural bond

syndrome. Social Science Medicine, 42, 21-34.

20

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

21/29

Lee, S., Leung, T/, Lee, A.M., Yu, H., and Leung, C.M. (1996). Body dissatisfaction among

Chinese undergraduates and its implications for eating disorders in Hong Kong.

International Journal of Eating Disorders, 20, 77-84.

Lee, S., Ho, P., & Hsu, L.K.G.(1993). Fat phobic and non-fat phobic anorexia nervosa: A

comparative study of 70 Chinese patients in Hong Kong. Psychological Medicine, 23,999-1017.

Markus, H. R. & Kitayama, S.(1991). Culture and the self: Implications of cognition, emotionand motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224-253.

Markus, Hazel R. & Kitayama, Shinobu (1991). Culture and the self: Implications of cognition,

emotion and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224-253.

Maynard, Michael L. & Taylor, Charles R. (1999). Girlish images across cultures: Japanese

versus U.S. Seventeen magazine ads. Journal of Advertising, 28, 39-50.

Matera, F. R. and Salwen, M. B. (1996). Unwieldy questions? Circuitous answers? Journalists

as panelists in presidential election debates. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic

Media, 40, 309-317.

McLeod, D. M., Eveland, W. P. Jr. & Nathanson, A. L. (1997). Support for censorship ofviolent and misogynic rap lyrics: An analysis of the third-person effect. CommunicationResearch, 24, 153-174.

McCout, J.M. & Waller, G. (1996). The influence of sociocultural factors on the eating

psychology of Asian women in British society. European Eating Disorders Review, 4,

73-83.

Meade, R.D. & Barnard, W.(1973). Conformity and anti-conformity among Americans and

Chinese. Journal of Social Psychology, 89, 15-25.

Miller, Mara (1993). Canons and the challenge of gender. The Monist, 76(4), 477-493.

Mukai, Takayo, Kambara, Akiko & Sasaki, Yuji (1998). Body dissatisfaction, need for socialapproval, and eating disturbance among Japanese and American College Women. Sex

Roles: A Journal of Research, 39, pp.751-758.

Perloff , R.M.(1989). Ego-involvement and the third person effect of television news coverage.Communication Research, 16, 236-262.

Perloff, Richard M. (1999). The third-person effect: A critical review and synthesis. MediaPsychology, 1, 353-378.

Powell, A.D., and Kahn, A.S. (1995). Racial differences in womens desire to be thin.International Journal of Eating Disorders, 17, 191-195.

21

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

22/29

Price, V., Huang, L and Tewksbury, D. (1997). Third-person effects if news coverage:

Orientations toward media. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 74, 525-540.

Reiger, Elizabeth, Touyz, Stephen W., Swain, Tony & Beumont, Peter J.V. (2001). Cross-

cultural research on anorexia nervosa: Assumptions regarding the role of body weight.International Journal of Eating Disorder, 29, 205-215.

Rojas, H., Shah, D. V., & Faber, R. J. (1996). For the good of others: Censorship and the third-person effect.International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 8(2), 163-185.

Rosenthal, D.A., & Feldman, S.S. (1990). The acculturation of Chinese immigrants: Perceived

effects on family functioning of length of residence in two cultural contexts. Journal ofGenetic psychology, 154, 495-514.

Rucinski, D., & Salmon, C.T. (1990). The other as the vulnerable voter: A study of the third-

person effect in the 1988 U.S. presidential campaign. International Journal of PublicOpinion Research, 2, 345-368.

Salwen, M.B. & Driscol, P.D. (1997). Consequences of third-person perception in support of

press restrictions in the O.J. Simpson trial. Journal of Communication,47, 60-78.

Shah, D. V., Faber, R. J., & Youn, S. (1999). Susceptibility and severity: Perceptual Dimensions

Underlying the Third-Person Effect, Communication Research, 26 (2), 240-267.

Shibata, T., & Nobechi, M. (1991). The cognition of masculinity-femininity of ones own bodyin adolescence,Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology, 39, 40-46.

Tiggeman, M. & Rothblum,E.D.(1988). Gender differences in social consequences of perceivedoverweight in the United States and Australia. Sex Roles, 18, 75-86.

Wan, F. (2001). The Impact of Idealized Images in Advertising. Unpublished Dissertation,University of Minnesota.

Wan, F. and William D. Wells (2001). How women and men perceive the thin

female models in media differently: Another exploration of the third-person effect. Paperpresented to Mass Communication Division at the 51st Annual Conference of

International Communication Association in Washington, D.C., May 24-28, 2001.

Youn, S., Faber, R. J., & Shah, D. V. (2000). Restricting Gambling Advertising and the Third-

Person Effect.Psychology and Marketing.

22

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

23/29

Table 1

Culture difference in terms of image-related behaviors

US HK Between Culture Analysis

Body image disturbance 2.98

(.88)

3.05

(.74)

F(1, 504)=.59, n.s.

Dieting 2.44

(1.23)

2.32

(1.14)

F(1, 505)=.83, n.s.

Frequency of exercising 3.02 a

(1.11)

2.45 b

(.84)

F(1, 504)=26.97, p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

24/29

Table 2

Perceived impact of thin female models in advertising on self and others

US HK Between Culture

Analysis

Perceived impact of thin

female models on

Self 3.34 3.28 F(1, 499)=.24, n.s.

Female friends 3.83a 3.69b F(1, 498)=4.32, p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

25/29

Table 3

The third person gap by social distance

US HK Between Culture

Analysis

Perceived impact of thin

female models on

Self 3.34 3.28 F(1, 499)=.24, n.s.

Close others 3.30 3.35 F(1, 489)=.90, n.s.

Self vs. close others .04 -.07 F(1, 489)=2.56, n.s.

Distant others 3.73 3.69 F(1, 489)=.50, n.s.

Self vs. distant others -.40** -.41** F(1,489)=.10, n.s.

Notes:

1. Cells with italic numbers refer to mean difference between perceived impact on self and others withineach culture. ** Within-culture comparison significant at p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

26/29

Table 4

The third person gap by gender identity

US HK Between Culture

AnalysisPerceived impact of thin female

models on

Self 3.33 3.28 F(1, 499)=.24, n.s.

Gender ingroup (female others) 3.93a 3.79b F(1, 489)=5.90, p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

27/29

Table 5

Coefficients of path analysis predicting dieting behavior

Body imagedisturbance

(Direct effect)

Dieting behavior(Direct effect)

Dieting behavior(Total effect)

HK US HK US HK US

Perceived impact of thin

female models on

Self .45** .61** -.04 -.01 .45 .56

Self vs. Female friends .13 .04 .01 -.06 .16 -.03

Self vs. Most women .01 -.01 .09 .21* .10 .20

Self vs. Male friends -.05 .16* -.07 .05 -.12 .20

Self vs. Most men -.04 -.14 .07 -.06 .02 -.19

Self vs. Romantic partner .10 -.06 -.04 -.16* .07 -.22

Body Disturbance / / 1.09** .93** 1.09 .93

Total R2 (%) 18.7 36.2 48.4 46.6 / /

Notes:

1. The path coefficients reported in the cells are unstandardized estimates. . **p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

28/29

Table 6

Coefficients of path analysis predicting exercising behavior

Body image

disturbance

(Direct effect)

Exercising

behavior

(Direct effect)

Exercising

behavior

(Total effect)

HK US HK US HK US

Perceived impact of thin

female models on

Self .45** .61** .53* .003 .57 .02

Self vs. Female friends .13 .04 -.23# -.01 -.22 -.01

Self vs. Most women .004 -.01 -.17# -.004 -.16 .001

Self vs. Male friends -.05 .16* -.24* .001 -.25 -.001

Self vs. Most men -.04 -.14# .03 .02 .03 .01

Self vs. Romantic partner .10 -.07 -.21# -.01 -.20 -.01

Body Disturbance / / .09 .02 .09 .02

Total R2 (%) 18.7 36.2 7.6 .03 / /

Note:

1. The path coefficients reported in the cells are unstandardized estimates. . **p

-

7/28/2019 Wan Faber Fung

29/29

Table 7

Coefficients of path analysis predicting likelihood of plastic surgery

Body image

disturbance

(Direct effect)

Plastic surgery

(Direct effect)

Plastic surgery

(Total effect)

HK US HK US HK US

Perceived impact of thin

female models on

Self .45** .61** -.03 .15 .11 .27

Self vs. Female friends .13 .04 -.09 .05 -.05 .06

Self vs. Most women .01 -.01 .08 .09 -.08 .09

Self vs. Male friends -.05 .16* -.06 -.10 -.07 -.07

Self vs. Most men -.04 -.14# .28* .28* .27 .26

Self vs. Romantic partner .10 -.07 -.39** -.36** -.36 -.37

Body Disturbance / / .31** .19* .31 .19

Total R2 (%) 18.7 36.3 14.4 18.2 / /

Note:

1. The path coefficients reported in the cells are unstandardized estimates. . **p