Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

-

Upload

asuncion-merino -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

0

Transcript of Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 1/15

The Cinderella Complex: Narrating Spanish Women's History, the Home and Visions ofEquality: Developing New MarginsAuthor(s): Robina MohammadSource: Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Jun.,2005), pp. 248-261

Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers)Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3804522 .

Accessed: 22/02/2011 11:24

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black . .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Blackwell Publishing and The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are

collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Institute of BritishGeographers.

http://www.jstor.org

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 2/15

The

Cinderella

complex

- narrating

S p a n i s h

w o m e n s

h i s t o r y

t h h o m

n d

v i s i o n s

o

equal i ty:

eveloping

n w

margins

Robina

Mohammad

This paper examines

the development

of feminism

in

Spain

within the

context

of

political

transformations.

It

focuses

on one

particular

strand

of

feminist

thinking:

/equality

feminism'.

The paper traces the

evolution

of

equality

feminism and

its

institutionalization,

supported

by the production

and dissemination

of a

feminist

history of the Franquista dictatorship (1936-1939). Yet, under scrutiny such narratives

maintain

a

silence on the social,

political and geographical

diversity

of

women's

experiences

prior to, during and

beyond

the

Franquista

dictatorship. Drawing

on

women's

oral testimonies

(recorded

in the city of Mdlaga,

Andalucia)

the

paper

animates

the

silences

of this feminist

history

in

Spain

and the limits of state

feminist

ideology.

key

words feminism state

equality

hegemony

ideology

silences

Mdlaga

South

Asian

StudiesProgramme,National

University

of

Singapore

email:

sasrm~nus.edu.sg

revised manuscript received 22 December 2004

Introduction

In Spain, a

strand of feminism

known

as equality

feminism

has

become institutionalized

in

the

state

apparatus. This paper

considers the

implications of

this for

workingclass

women. In

particular, t specifies

equality

feminism's

classifications

of labour

as

paid and

unpaid, public

and

private,

masculine

and feminine and examines their socio-spatial and

political

underpinnings

and

consequences.

Equality

feminism

(or socialist

feminism

as

it is

sometimes

referred

to) developed in

Spain

in the late

1960s

against the

backdrop of the

Franquista

dictatorship

(1939-1975) and was

heavily

influenced by

feminist

scholars

Betty Friedan and

Simone De Beauvoir.

After

the death of General

Franco

in

1975, the

dictatorship

volved into a liberal

democracy,a

process

which saw

the

curtailment of

the most

radical

currents

involved

in the

struggle

for

democracy

and the

reinstitution of

the bourbon

dynasty

with

King Juan

Carlos as

head of state.

Under pressure

from

equality

feminists,

the

socialist

government

that

came

to power

in

a

landslide

victory

in the

1982 elections

established

a state

department

for

women.

The

Instituto

de la Mujer (Institute

for

Women)

was

given the

mandate

to

develop

gender

equality.

Spanish

State Feminism's

(SSF)

govern-

ance

of the gender

'problem'

is coherent

with

the

liberal'

ideology

of the

democratic

state

of which

it

is a part. Its location within the state has provided

equality

feminism

with a

powerful

platform

from

which to disseminate

(and

universalize)

its

vision

of

what

counts

as women's

oppression,

the

con-

ceptualization

of women's equality

and how

the

latter

might be

achieved.

The

distinction

of public/private,

defined

in

spatial

terms

as 'la casa

o la

calle'

(literally,

the

house or

the street),

that underpinned

Franquismo's

gendered

ideology

is

also

key

to SSF discourse.

I

examine

how

this distinction,

aligned

with the

modern/traditional

binary,

became

central to

hege-

monic feminist

representations

of the home. For

TransInst Br

GeogrNS 30 248-261 2005

ISSN 0020-2754

?

Royal

Geographical Society (with The

Institute of British Geographers)

2005

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 3/15

The

Cinderellacomplex

this I

draw on

two

interviews with

feminists

work-

ing

within the

municipal

state women's

office in

Malaga, the

Delegacion

Municipal de

la

Mujer,

and

two

from the

regional state

women's

office

in

Andalucia,

the

Instituto

Andaluz de la

Mujer. I

supplement these interviews with an extensive

study

of

literatures

(many

of them

produced

and/

or

funded by the state

offices) that relate to and

inform

the

production

and

circulation of

everyday

narratives about

women's

place

in

Spanish

society.

Then,

drawing

on an

in-depth

intergenerational

study

of 44

working-class

women aged

between 19

and

72,2 located in

Malaga

Town

(Andalucia),'

I

consider

the extent to which

women's

subjectivities

have

been

produced

within SSF

discourse with

reference

to

understandings of

gender

equality,

freedom, home and work. I show how SSF's con-

ceptualization of

gender

equality

serves to

valorize

some

women while

marginalizing others.

Pursuing

what

Squires (1999)

refers to as

a

'strategy of

inclusion',

SSFseeks to

make women

equal to men.

In

this vision,

equality

between men and

women

requires not only

the

development of

equality of

opportunities but also

the

production of

a

model

of

Spanish

womanhood

capable

of

taking up these

opportunities. Thus

part

of

its

aim

involves the

transformation

of

women.

However,

this

strategy

leaves the

structures within

which

inequalities

are

produced unquestioned.

Retaining a centre

supports

a

periphery.

Those women who have

the

capacity

for

achieving equality

according

to

SSF's vision

are

centred,

but

those

who

refuse

it

or

those less

cap-

able

of

this

transformation, such as the infirm

and/

or

disabled

women

unable

to

engage

in

paid

work,

remain

relegated

to the

periphery.

I

argue

that

in

keeping with

liberal

ideology, SSF

discourse on

the

one hand

promotes

women's

autonomy, free-

dom and

liberty. Yet

on

the other

hand,

it

limits

and

controls, by

prescribing

a

particular model of

womanhood and valorizing it over others. Finally,

the

focus of SSF

discourse,

in

keeping

with

certain

hegemonic strands

of

Anglo-American 'second

wave'

feminisms,

has been almost

exclusively

on

the

inequities produced

by gender.

But

as

critiques

of

the

latter

have

pointed

out,

the

man/woman

binary that this

privileges has

generated

new

oppressive

fictions

even

as

it

has

sought

to

address

existing

ones. The structure

of the

paper

is

as

fol-

lows:

I

begin by

tracing Friedan and

De

Beauvoir's

influence

on

feminist agendas

in

Spain

(Amoros

1986; Folguera

1988) and

the

emergence

and

insti-

tutionalization

of

equality

feminism.

I

then

discuss

249

SSF's post-dictatorship

re-narration

of

Franquista

history,

within a liberal

framework, against

which

women's equality

has been

conceptualized.

Draw-

ing on interview

data

I examine

the extent

to

which

this history

as a collective

memory has been

pro-

ductive of women's subjectivities. From the basis

of respondents'

experiences

I

highlight

the

partial

nature

of this collective

memory.

Puertas adentro4

(behind

closed

doors):

queens

and/or slaves

of the home.

Equality

feminism

in

Spain

[The]existence

of a regime

which denied

citizens virtually

all forms

of meeting

and

association

made it. ..

[difficult

to organize

resistance

movements

in

the late-1960s

and so] much more difficult for the ideas and actions

launched

by women

in other parts

of Europe and

North

America

to catch on

in Spain. (Threfall

1985, 45)

Equality

feminism

developed

within the women's

movement

gathered

pace

as

part

of an

oppositional

movement

in

Franquista Spain

in

the late

1960s.

Although

the anti-democratic

environment

aimed

to

inhibit all forms

of

opposition,

socio-economic

transformations

encouraged

the

new

generation

of

women

to

question

their

own

position

in

Spanish

society.

As Escario

et al. note:

For the first time, women were reflecting more on their

rights

than their duties

and obligations.

(1996,

50; see

also

Morcillo

1988;

Scanlon

1990)

Internationally,

in

the

Anglo-American

world a

second

wave

of feminism

was

at

its

height.

In

the

United

States

civil

right

struggles

were being

fought

and

won;

closer

to

home students were

agitating

in

Paris,

France.

In

Spain,

the

numbers

of

feminist

texts

that had

been

filtering

in and

circulating

llegally

since

the

early

1960s

(Borreguero

et

al.

1986;

Morcillo 1988;

Scanlon

1990)

were on the

rise, encouraging women to recognize as illusionary

the choices

offered

them

by

the

Franquista

regime

(LUpez-Accotto

1999).

These

texts

were to

have

an

important

influence

not

only amongst

feminists but

all women

who

in

those

years

began,

for

the first

time,

to feel a

sense

of rebellion

against

their

traditional

role.

(Escario

et al.

1996, 50)

Most

notable

of these texts

were

Betty

Friedan's

The

feminist

mystique first

published

1963)

and

Simone

De Beauvoir's

Le

deuxieme

exe

(The

second

sex,

first

published

in

1949) (Thornham

2001).

A

Spanish

copy

of

the latter

found its

way

into

Spain

from

Argentina

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 4/15

250

in 1962.

Circulating

clandestinely,

as Cafias

notes

in

an

article

commemorating the

fiftieth

anniversary

of

the

book,

it

quickly became known

as

the

feminist

bible. It

was passed

from hand

to

hand.

[I]n it many Spanish women encountered a profound

reflection

(with

respect to

the

condition of

women) on

what

they already

knew

intuitively.

(1999a,

32;

my

translation.

See also

L6pez

Pardina 1999)

What

was

already

known

intuitively

was

further

developed

and

formulated

through the

lens

offered

by

Betty

Friedan.

Friedan's The

feminist

mystique

(1963),

focusing on

the

experience of

housewives in

the

United

States in the

1950s,

argued that

patri-

archal

American

society saw

the

roles

of

housewife

and

mother

as the

'natural'

destiny of

women

because of theirbiologicalcapacity for reproduction.

This

destiny is

further

naturalized

by the

seductive-

ness

of the

ideologies of

love

and

romance

circulated

through

the

media,

promoted

by

capitalist

consump-

tion

as

well as

by

'experts' in

medicine

and

health

guiding

women towards

particular

feminine

ideals

(see

Jacobs

Brumberg

1998).

Friedan

(1963) argued

that

this

undermined

women's ambition

to

excel

in

the

public,

professional

worlds,

drawing them

instead

towards

the

limited and

alienating

private domain

of

the

home

through

marriage and

motherhood.

Writing at

the height

of

Fordism

when

the dis-

tinction between the

spaces of paid and

domestic

labour

was

most

marked, Friedan

contrasts

both

the

forms

of

labour

-

domestic and

paid, as well

as

the

sites

in

which these

activities are

under-

taken.

She

points

out that

against

the

tedious

monotony

of

domestic

labour,

undertaken

for love

and

largely

unrecognized

or

recognized

in

ways

that

do

not

count, paid

work is

mentally

stimulat-

ing.

Moreover,

it

has

marked

temporal

boundaries,

offers

a

wage

and

financial

autonomy,

promotion

and a

recognized

status.

Yet

for Friedan

crucially

the site of domestic work itself - the home - is par-

ticularly

alienating

and

disempowering. The home

removes

women

from the

apparently

transparent

public

sphere

and

makes them

less

visible.

They

are

disenfranchised by

their exclusion and

invisi-

bility

from

the

arenas

of

institutional

politics

and

government,

and

the labour

market,

denying

them

full

participatory

citizenship.

These

ideas

found

resonance

in

a

Spain

in

which a

national

form

of

Catholicism, as

the state

ideology, per-

suaded

boys

and

girls

towards

separate destinies

that

were also

spatialized.

The 'natural'

destiny

for

men

was the

public

world, and

for

women,

the pri-

RobinaMohammad

vate

space of the

home and the

twin roles of wife

and

mother (Riera

and

Valenciano

1991).

However,

feminist

currents

in

Spain

were divided over

what

counted

as

oppression.

For example,

in contrast

to

equality

feminism,

difference feminism

views 'the

spaces of [women's] personal, lived experience as

the only legitimate

starting-point'

(BrooksbankJones

1997,

11). Difference feminism

celebrates

the spaces

of

the

home,

of

the

'vida cotidiana'

(everyday

life),

the very spaces

that

equality

feminism

sought

to

negotiate

women's

release

from.

Feminist

currents

were

also divided

over the

means for developing

women's empowerment.

From

equality

to state

feminism

McBride Stetson and Mazur reflect on how

The

most

striking

consequence

of over 25 years

of

women's movement

activism has been

the

array

of

institutional

arrangements

inside democratic

states

devoted to

women's policy questions.

(1995, 1)

However, feminists

have

been unable to

come

to

any agreement

about

the role of the state

in

the

achievement

of their objectives.

Marxist

and Radical

feminists

view the

state as

an

instrument

of

capitalism

and

patriarchy respectively

(see

Elshtain

1983;

MacKinnon 1989).

In

the

Spanish

context,

radical

feminists regard

man as the oppressor,

rather

than a patriarchal, socio-political-economic

system,

thus they

ruled out the

possibility

of col-

laboration

on

projects

of

resistance

that

involved

an

engagement

with

institutional politics.

Differ-

ence feminists,

who

privilege

women's knowledges

and

viewpoints,

believed

that

any

engagement

with formal political

structures would

inevitably

and irrevocably

transform feminists themselves,

compromising

the commitment

to their

own

and

collective

autonomy.

By contrast,equality

feminism's

liberal view does not see the state as an instrument

of

oppression,

but rather

as

a

facility

that can be

used

by any

group

able

to

develop

the

political

capital

to

promote

its own vision

of the world.

State

power

can be harnessed

to

develop equality

between men

and women

(Riera

and Valenciano

1991).

It

is

this

position

that enabled

equality

feminism

to achieve

hegemony

over alternative

feminist

visions

through

its

institutionalization

with

the

establishment

of

the Instituto de

la

Mujer (the state

women's office)

in

1983.

Taking

their cue from

the national

state, regional

and

municipal

authorities

also set up women's

offices.

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 5/15

The Cinderella

complex

In

Andalucia,

for

example, the

regional

state

women's

department, the

Instituto

Andaluz de la

Mujer,

was formalized

in 1988.

Mdlaga's

Delegaci6n

Municipal de la

Mujer was

established

more

recently in 1994.

At this point I should note that by SSF I do

not

simply refer to

the formal

political

apparatus

of the

state, but to

the network of

agencies and

technologies

through

which

governance is achieved.

Governance

draws together and

produces

'a profu-

sion

of

shifting alliances between

diverse authorities'

(Rose and

Miller 1992, 174),

all those

involved in

knowledge

production,

including

academics, jour-

nalists,

teachers,

medical and

health

authorities,

experts

on

populations, the

physical

and

social

environment,

industry and

economy. Such

authori-

ties form a complex web that imbricates state and

non-state

actors

in

such a

way that it blurs

the dis-

tinction

between

state and civil

society. Fentress

and

Wickham argue

that 'social

groups

construct

their own

images of

the world by

establishing an

agreed

version of the

past' (1992,

ix-x) achieved

through

research and

knowledge

production. Thus

funding research on

gender issues and

dissemina-

tion of

the findings is

key to

governing the problem

of

gender

inequality.

So, Lambea Pefia

notes

how

the

Instituto Andaluz

de la

Mujer started business

'with a

study of the

social situation

of Andalucian

women in order to diagnose reality' (1999, 24);

the

Instituto de

la Mujer also

stresses the

need 'to

make a

reliable diagnosis of

the situation'

(1997,

17).

Connected by a

shared vision,

and an informal

commitment

to cooperation

and

coordination

of

initiatives,

state women's

offices have

at their

disposal

extensive

technologies to

mould Spanish

womanhood in

ways that

parallel the

dictatorship.

The Instituto

de

la

Mujer's

Equality

Plan

stresses

that

education

is the basic

instrument

to

achieve

equality

of

opportunity

...

an

essential element for the

autonomy

of

women,

so

they

are able

to

develop

their own

opinions

...

(Instituto

de la

Mujer

1997, 15)

Women

must

develop their 'own

opinions',

but

must

do so

in

accordance

with

equality feminism's

vision, so the

Proposal for Action

26

in

the

Instituto

Andaluz

de la

Mujer's (1995)

Equality Plan

(current

at

the

time of

writing) calls for:

Campaigns

of awareness and

training

in

non sexist

orientation

[to

be]

directed to

families

and

students

with

the

objective

of

transforming

their

attitudes

to

their future

choice of

profession.

251

State

women's

offices

draw

on experts in

a

range

of

fields

to direct

women.

Both

the

Instituto

Andaluz

de

la

Mujer

and

the Instituto

de

la

Mujer

publish

extensive

material to

inform

and

guide

women,

ranging from

books

(produced

from

a variety

of

disciplinary locations) to free guides and booklets

advising

women on

a range

issues such

as

em-

ployment

(for example,

a guide to

reconciling

family

and working

life), domestic

violence,

sexual

health

and

educational

choices.

At

the same time,

their involvement

in

the

production

of knowledges

allows state

women's

offices

a

privileged

role

in

the production

of a collective

memory

of

women's

history

which

acts as

a basis for

the formulation of

gender

equality

programmes

and

provides

legitimation

for

equality

feminism.

Re-narrating

Franquista

Spain:

women

as 'other'

Fentressand

Wickham

argue that

individual memory

becomes

transformed

into a social

or collective

memory 'essentially

by

talking about

it'

(1992,

ix-x).

Yet

it

is

not simply

having

a voice

that is sig-

nificant

in this process,

but being

heard.

It

is the

narratives

of

the privileged,

of

those

who have the

status

and

resources,

to

circulate,

normalize and

universalize particular

knowledges

or versions

of the

past.

At

the

same

time as Summerfield

points

out,

local and particular

accounts

[of

the past]

cannot escape

the

conceptual

definitional

effects

of

powerful

public

representations

...

[thus

p]ersonal

narratives

draw

on

the

generalised

subject

available

in discourse

to

con-

struct the particular

personal

subject. (1998,

15)

Thus, for

young women,

public

representations

act

as a memory

of the Franquista

years.

Yet

powerful

public

representations

also

work on

the

memories

of older

women

who

have lived

experience

of

the

Franquista years. The collective memory prompts

and

guides

recollections,

infusing

and

enhancing

personal

memories

of

lived

experiences.

It

is able

to animate

and

re-configure

recollections

into

new

constellations,

endowing

experiences

with

new

meanings.

At

times

it

may

even

overwrite those

memories.

Thus the

act of remembering

is

highly

ideological.

Lorde

Enders,

with reference

to

historiography,

notes

how

after the end

of the

dictatorship hegem-

onic

power

belonged

to the centre

and

liberal

left.

The '[f]ormer

winners were

now losers,

and their

story

rested

in

the

hands

of their

political

enemies'

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 6/15

252

(1999, 389).

It is in this

context

that

re-narrations,

whether

self-consciously

propounding

equality fem-

inism

or

otherwise, have a

tendency to

conceive

the

dictatorship as a

regime that

disrupted

Spain's

'natural'

progression from

'tradition'

to

'modernity'

with profound implications for women. Women's

distinctiveness

and

differences

from men

were

reinforced by a

dictatorship,

ideologically commit-

ted to

'tradition'.

Under the

command of

General

Franco,

Nationalists seized

power in

1939 and

emerged

victorious

in

a

bloody

civil

war fought

against the

democratically

elected,

liberal left

regime

of the

Second

Republic

(1931-1936).

In this

narration the

Second

Republic

becomes a

regime

that

liberated women

from tradition to

modernity.

Alted, for

example, notes

the

'favourable climate'

for women, during the Republicand even during the

Civil War

in

the Republican zone. This

'translated

into a

series of

conquests on

three

fronts:

juridical

equality with men ...

equality

of

opportunities

with

respect

to

education5 ...

[and]

protective labour

legislation...' (1991,

301). During this

period

women

were

granted

suffrage.

Moreover,

they were to be

liberatedfrom the

home

through the

divorce legisla-

tion

(Moxon-Browne

1989). It is against

these

Repub-

lican reforms

that

the

Franquista egime is

constructed

as a

'return to

the past';

'returning

women'

(Aline

Barrachina

1991, 211;

see also Carerra

Sudrez

and

Vinuela Suirez 2001) to the home, pushing women,

back from

'modernity' to 'tradition'

given

that

the

ideology of

the

[Franquistalregime with

respect

to

women

was

based on the exaltation of

their traditional

roles of

wife and

mother

confined to

their homes.

(Riera and

Valenciano 1991,

40)

Thus the

dictatorship

reversed the

progressive

re-

forms

made

under the

Republican

regime.

National

Catholicism6

provided

an

ideological

framework

for the

reproduction

of

the nation

(Nash

2000).

It

put the Catholic family, characterized by gender

divisions

and

hierarchy,

at the base of

Franquista

society,

as the

vehicle for a

conservative

national

regeneration.As

the

preamble to the

Labour Charter

of

1938

stated,

the

family

is the

'primary natural

and

basic

unit

of

society

and at the

same time

a

moral

institution'

(quoted in

Del

Campo

1991, 88).

Historically

speaking,

the

relegation of women

to the

home, as studies

have

shown, is not new.

In

Spain

'[t]he home

was a

feminine

space, [that

was]

completely

enclosed' (Ortega

L6pez 1988,

43).

Spanish

women,

as

women

elsewhere in

Europe

and beyond, were directed towards the home less

Robina

Mohammad

by

the state

and

more

by

economic necessity.

In

this sense,

marriage

acted

as a

refuge,

a tactic

for

survival (Scanlon

1986).

The

significance

of

mar-

riage

in

turn

imposed on women a life enclosed

behind

the walls of

the house

[which

they

left only]

for

pious

visits

to

the

Church; [other

than

that they

remained

within

the

four

walls of

the home]

hidden

from the view

of strangers,

in the

Arabic mode

... (OrtegaL6pez

1988, 43)

Marriage

not

only

naturalized

the

home as the

place

of

married women

through

their

roles as

housewives

and

mothers,

but it

also

prepared

the

ground

to contain

women,

not

yet

married,

to the

space

of

the

home

and reinforce

the worlds

beyond

it

as

essentially

masculine.

Catholicism

stressed

the centrality

of

women's

virginity/heterosexual

purity to marriage which became a measure of

women's

value in the

marriage

market.

In turn

this encouraged

constraints

on

single

women's

geographical

and

temporal

mobility.

At this

point

it is important to

bear

in mind

that the

Second

Republic, despite

legalizing

divorce,

did not

seek

to

address

in

any

substantial,

material

way

women's

economic dependency

on

marriage.

But the collective

memory foregrounds

the

ways

in

which

the Franquista

state sought

to

retain

women

in

the

home

through

a

variety

of direct and

indirect measures. As Scanlon points out

'La

mujer

de su casa'

[the

women

of the

house]

was

an integral part

of

Catholic

and traditional

Spain

that

Republic[an

policies]

had intended

to destroy

and

which

the

Nationalists endeavoured

to restore.

(1986,

337)

For

this the

Franquista

regime

drew on

the

Seccion

Feminina (the

Franquista

state's

de facto women's

office)

which

acted

as a

'political

instrument to

organise

women and

to transmit

the

thinking

and

values

of

the

new

state'

(Riera

and

Valenciano 1991,

43).

More specifically

its

role

is remembered

as one

of 'exhort~ingi .

..

women to reduce themselves to the

home

and to

the

Church'

(Pardo

2000,

dust

jacket).

Franquista policies

encouraged

women to leave

paid

work

upon

marriage,

and to

have

more chil-

dren.

From

1942,

women

employees

in the

public

sector

were offered

a

carrot,

'la

dote',

a financial

gift,

to leave

paid

work

upon

marriage.

'Once confined

[within

the home] they

were much

easier

to

control'

(Carbayo

Abeng6zar

1998, 35).

Married women

could

only legally

engage

in

paid

work

with

the

formal

permission

of their

husbands.

In

addition,

legislation

was

put

in

place to

bind women more

closely

to the home through motherhood. On the

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 7/15

The

Cinderella

omplex

one

hand,

the

regime

called for

sexual

abstinence

and

was

vigilant

against the

sin of

solitary

sexual

pleasures

for

daughters in

the

parental

home

(see

Ortero

1999b). On

the

other,

as

wives, it

insisted on

their

participation in

conjugal

relations for

the pur-

poses of procreation. The regime's plan to increase

population

numbers saw

the

re-establishment of

Mother's

Day

(Ortero

1999a).

Women

were

reminded

that

'making

Spaniards

makes Spain

great'

(Seccidn

femenina,

quoted

in

Ortero

1999a,

111).

Pro-natalist

policies

were put in

place by

a

regime

that

'[riejected

[birth

control]

in a

rhetoric

that

chastised

the moral

decadence of

the

Republican

period'

(Nash

2000,

298). The

sale,

purchase, adver-

tising and

use of

contraception was

prohibited and

abortion

was

criminalized. At

the

same time

the

establishmentof the FamilySubsidy in 1938(offered

on a

sliding

scale

to

family

heads,

usually

male)

was a

measure to

persuade

women to

have

chil-

dren.

General

Franco's

own

ministers had

to set an

example to

the

nation, so

they were

all

fathers of

numerous

children (de

Miguel

1976).

These

policies

also

sought

to

ensure

that

wives

and

mothers

from

poor

families would

not be

forced

by

the burden

of

poverty to

enter

the labour

market

(de

Miguel

1976;

Nash 1999

2000).

A

wife's

engagement in

for-

mal

paid

work,

however, was

further

undermined

by

the

threat of

withdrawing the

family

subsidy

from her husband

(Roig 1989).

These

measures

were

introduced at

least

in

part

to

contain

women to the

feminine

sphere.

But

as

Shubert

notes, it

was

middle- and

upper-class

women,

far

more that

working-class

women who

'found

their world

and

especially

their contacts

with

men

severely

restricted'

(1992,

214).

It

is

in

this

context

that

Friedan's

analysis found

common-

sense

appeal

amongst

educated,middle-class

women,

in

a

country

that

until

the

economic

miracle

of

the

1960s

was

sharply

polarized

in

socio-economic

terms. It is against this narration of Franquista

policies that

equality feminists

identified 'the

two

great

problems that ...

had

to

[be]

confront[ed

-],

matrimonyand

maternity'

(Carbayo

Abeng6zar

1998,

25).

Sociologist

Ma

Angeles Duran

reminds women

from

the

pages of

the

Instituto

Andaluz de la

Mujer's

journal

Meridiana,

hat

it is

very difficult

for

women to

obtain a

real freedom

while

they

[women]

continue to

[make

up]

the

majority

of

those

who take

charge

of non

remunerated work

[in

the

home] that is

necessary

to

maintain

the

country

in

the

levels

of welfare and

comfort

that

are

in

place

at

present ...

[in

other

words] while

women

assume,

as

253

occurs

in

reality, 80 per cent [of

the

responsibility]

of non

remunerated work

and

only

30

per

cent of

remunerated

[work]

their access to liberty [will

be] very

reduced ... (Durdn1999, 9)

To attain freedom women

must be released from

the home

so that they can flood

out

and

become

visible

in

the public, masculine

arena

(Durdn

1987;

Vargas

1995). Thus the projectof

SSF

aims to

loosen

and break the chains

that

link

and bind

women to

the home,

at

both

the

legal

and

ideological level.

From the

'Other' to the

'Same'

While Friedan

(1963)

offers a framework

through

which to conceptualize

the 'problem' of gender

inequality, De Beauvoir provides

a clear direction

for its resolution. De Beauvoir confirms that the

meaning

of 'woman'

is

not innate,

in

that

it

does

not

have an inherent

nature. She insists that

womanhood is socially

constructed

in

relation

to

the

meaning of man. Woman

is that

which

is not

man.

If

man is the 'Same'

then she is

his

'Other'.

She

is

placed

in a violent

hierarchy

that

locates

her

as

the subordinate of

man. So

[wioman

... [must become] like man,

in

order

to escape

the debilitating

and

endlessly disempowering

impact of

femininity

as

the

condition

of otherness.

Refusing

this

condition becomes, for De Beauvoir, the definitive

feminist

project.(Evans 1997,

45)

A

refusal of

this condition

not

only depends

on

legislative changes

but

requires

a

transformation

of

women. The role

of

SSF, therefore,

is also one

of

'making up'

women

as citizens

capable

of

being

modern, equal, independent

and

liberated (Rose

and

Miller

1992).

Brooksbank

Jones

notes how 'no

study

of

Spanish

women

can avoid

...

[the]

binary

[of

tradition and

modernity]' (1997, vii).

Just as

the

issue of

women's

equality

vacillates

around

and between these two poles, so too does national

identity. Historians,

for

example,

have

identified

at

least two

Spains:

the

inward-looking Spain

of

traditionalist

Catholic values

...

[and a

liberal7]

Spain

of

progress

and

free

thought

which looked

to

Europe

...

(Carr1980, 12)

The

latter

viewed

'regeneracionismo'

or

national

regeneration

n

terms

of

development,

modernization

made

synonymous

with

Europeanization (Holman

1996).

In

1977,

with the end of

the

dictatorship,

the

desire

for liberal

regeneration

saw

the

disbanding

of the Secci6n

Femenina

(Loree

Enders

1999),

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 8/15

254

and

supported the

institutionalization

of

equality

feminism. The

development of

democracy was

key

to

a liberal

regenerationof the

nation. Thus

equality

feminism

was able to

purchase

support for

its

institutionalization

(Escario et al.

1996) by linking

its project to democracy and national advancement.

Just as

Liberal Spain

seeks inclusion

amongst the

advanced

nations of

Europe, so SSF

seeks

the

inclusion of

women within

the arenas that

they

have

hitherto been

excluded from

(Instituto de la

Mujer

1997).

Collectively

this is

imagined

as

a

linear journey, a

transformation

from 'tradition'

to

'modernity'

(see, for

example, Borreguero

et

al.

1986),

from difference to

sameness.8

Transformations

Now

I

don't

have to be a woman

anymore.

I

need never

become

a

mother. Being a

woman

has

always been

humiliating, but I used

to

assume there was no

exit.

Now

the

very

idea 'woman' is up for

grabs. 'Woman'

is

my slave name;

feminism will

give me freedom to

seek

some other

identity altogether.

(Snitow 1990, 9)

Mujer,

liberate de la cocina

y unite.'

(Woman,

liberate

yourself from the

kitchen and

unite) (Escario

et al.

1996,

271)

Escario et

al's (1996)

study documents

the

history

of

the

women's

movement in Spain from

the late

1960s. I will draw on it to examine the initiatives of

equality

feminists, who with

a

zealous enthusiasm

(note

how De

Beauvoir's

The second sex was

termed the

'bible' of

feminism; Cafias

1999a, 32)

sought to reach

out to

women and

transform their

consciousness.

Having

identified

matrimony and

maternity as the

problems

to be

addressed,

consciousness-raising

initiatives by feminists

involved

cautioning women

that

marriage was a form

of dependence and

only

those who

engaged in paid

work were

able

to

become equals. They were advised that '[in some

way

[through marriage]

you have sold

yourself

to

the

person

who

[financially] supports

you' (Escario

et

al.

1996, 67).

Moreover,

women were called

on

to

reject

motherhood

because children

were seen

to

encourage

their

dependence on

men. As an

example

of

this,

in

recounting

her

experiences,

one feminist

noted how

she was

pregnant when

our

debate

on

the

rejection

of

maternity/motherhood

took

place: it was

[constructed

as]

the

fruit and the

origin

of all

our

problems

and

it

had

to

be

refused.

That

discussion

seemed brutal

to

me.

(Escario

et al.

1996,67-8)

Robina

Mohammad

These

ideas and

demands

led to a conflict

of

interests

with women

who had

male

partners

and

children,

so

that

There were

women

who came

and said

I can

not

continue listening to you because it is turning my

family

life up side

down. (Feminist,

quoted

in

Escario

et

al. 1996, 165)

L6pez-Accotto,

in her account

of

the

development

of feminism

during

the 1970s, registers

how

the

different

'histories, desires

and

needs

...

led to

not a few

misunderstandings'

(1999, 117),

but this

recognition

did little

to

challenge

the idea

of a

universal

sisterhood

in which

all women

share

a

common

experience

of

patriarchal

oppression

and

common goals

of modernity

and

equality (for

a

critique

of this in the context of Third World feminisms see

Spivak

1988;

Mohanty

1998).

For

equality

feminism,

the difficulties

in

appealing

to women across

differ-

ences becomes

merely

a

problem

of

communication

that

in

time

can be resolved

by

developing

the right

language

to represent

the reality

of women's

opp-

ressed

lives. By 'dressing

it

up'

as something

familiar,

equality

feminism

could

be

made

meaningful

for

women.

But

if 'traditional'

women

stubbornly resist

new

ideas,

change and

'progress',

then newer gen-

erations

will

be

more open

to

it

and have

a

greater

potential

to be 'modern'

and

equal.

Development

ndprogress

As

with

the

Spanish

liberal regenerationist

discourse

of the

nineteenth

and

early

twentieth

centuries,

SSF

associates

modernity

with the future,

with national

and

personal

'advancement'

(Romero

Perez

1999).

Progress

and

youth

are made

synonymous,

while

tradition

is

associated

with

the

past,

with backward-

ness, with

constraints

and

age.

As Carrasco10

t al.

note,

'egalitarian

attitudes',

regarded

as a

feature

of the

'modern',

'continue being

strongest

amongst

the youngest' (1997, 75). Borreguerroet al's (1986)

collection

of studies

mark and

celebrate women's

journey

to

the

'modern',

the

slow,

but

sure,

emerg-

ence of 'a

new

woman

who,

day by day,

is

gaining

ground'

(Capel

1986, 27).

In their study11 of

moth-

erhood and

women's participation

in

paid

work

(funded

and

published

by

the

Instituto de la

Mujer),

Violante

and

Quintana

argue

that these 'new'

women

'mark

..,

a

profound

change

in

mentality

which manifests itself

in

the

modernisation

and

progress

of

Spanish

society' (1992,

88).

As

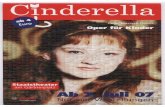

a

flyer

(Plate

1)

for

the

Instituto

Andaluz de

la Mujer's

campaign

remarks of

these

women:

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 9/15

The Cinderellacomplex

mas preparada

para

el

futuro

prepard

Ir the

future)

m

5

parti~ci

ativa

Om~s

moidrnma_

(moe

m

era

(mote em e)y

Plate 1

Source: Instituto Andaluz de la

Mujer

(translation

added)

[S~he

s a more

independent

woman with a

higher

level

of

education,

who not

only

searches

for,

but desires

remunerated

work,12

who is

sexually

more

free

[and]

less

likely

to abide

by

ancestral

concepts

and

the

Church.

(Capel

1986,

27)

Moreover,

it is the

desire to want to do remunerated work ...

[that

in

turn]

is

breaking

in a

dizzying

manner and without

any

order,

the feminine moulds of our civilisation.

This

fact is the result

of an

important change

of

mentality produced by

their

[women's]

conformation

to

industrialisation and modernisation of our

society

...

(Violante

and

Quintana

1992,

3)

Those women who have conformed are

responsible

for

the

high

increase

in rate of women's

[economic]

activity

[that]

...

constitutes a relevant indicator of the

process

of modernisation

in

the

Spanish society.

(Instituto

de la

Mujer

1993,

30)

Modern,

middle-class

women,

viewed as

key

to

national

progress

and therefore

an

important

national

asset,

are

targeted by equality programmes.

As

politi-

cian

and

scholar, Senator Victoria

Camp points

out:

When

we talk about

women's

liberation

we have in

mind

those women who can allow themselves to

choose between

working

and

not

working

-

middle

and

upper

class women. We have in mind literate

women who can be

interested in

jobs

other

than

cleaning

and

caring

for children.

(1994,

57)

255

. . .

.

. . . o . . . . . . . .

.W

~

j

Plate

2 The

same

opportunities,

equal

-

equal

They

are

visualized

by

the

Instituto

Andaluz

de

la

Mujer

flyer (Plate

2) promoting

equality

in

the

home

and

at

work.

Note

how those portrayed

are

all able

women

who

are either studying

or in

paid

work. They

seem

more European

than

Spanish

and

are likely

to be secular

rather

than

religious.

Yet

while

it is important

to celebrate

the

'very

important

rise

...

principally

[during

the 1970s

and 1980s],

in

the rate

of

non

single

women's

participation

in

labour

activity'

(Violante

and

Quintana

1992, 88),

the

home

continues

to wield

a

strong

grip

on

women.

This

is

particularly

so

for

those

with

the

responsibilities

of

motherhood

and/

or

caring

for the

sick,

elderly

or

disabled.

A

study

by

the

Cabinet

Office

Women's

and Equality

Unit

(2001)

in

Britain

shows

how

women's

association

with the home is difficult to break. The pay gap

between

men and

women

persists

(although

to a

lesser

degree)

even

for

those

who

are

more skilled

and

have elected

to remain

childless

(Cabinet

Office

Women's

and

Equality

Unit

2001).

Nevertheless,

part

of resisting

the hold

of the home

for

'modern'

women

translates

into

a

resistance

to

motherhood.

'Modern'

women

are

more likely

to be

single

and

if

married,

childless (for

a discussion

of

the rela-

tionship

between single

life,

modernization

and

national

advancement

see

Alborch 1999).

The

sharp

fall

in

Spain's

birth rate,

now

the lowest

in

Europe,

(Otamendi

1999;

Cafas

1999b

1999c

1999d)

is

not

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 10/15

256

only an

indicator

of the

availability

of

contracep-

tion

and

information, and

economic

peaks

and

troughs

(Garrido

1993), but

also the

lower

social

value

placed

on

motherhood and

mothering. The

refusal or

deferral

of

motherhood

enables

women

in their quest for the colonization of masculine

spaces

(Violante

and Quintana

1992).

Disjuncture:

breaking he

chains

My

respondent

Cristina, aged

38,

is

married and in

part-time, paid

employment. She

is

classified, and

importantly

classifies

herself, as a

modern

woman.

Thus,

when

we

asked

Cristinahow

her life

compared

with

that

of her

mother's,

she

stressed

that 'my

life

is

much

better

than

that of

my

mother'.

Matilde'3

then

questions

her

about

why this

is so. Her

response is that her life is different:

firstly

in

the

objectives that

mark

you,

the

desire to

break

with

the

established.

I

am

concerned to

participate

in

breaking the

things I

see

that are

most

traditional.

It

is no

surprise,

therefore, that

when

she is asked

if

she

feels that

having

children is

important,

she

replies '. .

. yes.

For

those that

want

them'.

'Are

they

important

to you?', Matilde

persists.

No.

I

believe that

a woman

today

is

not fulfilled

by

motherhood

alone.

I

have been married

almost

13

years

and I am still fulfilling myself personally. I haven't

noticed

a

lack of

anything.

Her

refusal of

motherhood cannot

be

understood

as

separate

from

her

quest

to

break with

what

she

views

as the

most

traditional

elements of

society.

'Traditional'

women are

perceived

as

economically

dependent,

with

the

values

of

self

sacrifice,

passivity

and

obedience

cultivated

in

them

by

the 'hated

regime' (di

Febo

1979;

Scanlon

1986;

Morcillo

1988;

Loree

Enders

1999,

378; Morcillo

Gomez

1999;

Nash

2000).

If

these women

represent

femininity

then, young 'modern' women vehemently decline

any

association with it.

This is

evident

in

the

attitudes of

my

respondents towards

the

feminized

home and

'work'.

It

is

particularly

notable

amongst

those

aged

45 and

under,

including those

who have

had

closer

encounters with

the

Franquista

state and

/

or

whose

subjectivities

have

been

produced

to a

greater

degree

within SSF

discourse.

Boundaries,

bounded,

a bind

Young

generations

[of

women] who have

been

educated

within

models of

equality

[are]

better

prepared

(trained)

Robina Mohammad

and are [accustomed to]

an

environment

that is

more

competitive

in

every respect,

without

doubt, they have

a very different

attitude

from their

mothers

towards the

world of work. (Sarasia 1995, 6)

In this section I look at women's attitudes to the

home defined

with

respect

to forms of work.

I

note a high level of consensus particularly amongst

women aged 45 and under,

which

progressively

declines amongst older

women. With

respect

to

work

in

the home

and outside

of

it,

two

points

are raised constantly by

the

youngest respondents.

These are made here by Mata, aged 23, the

daughter of Benita (aged 55). Comparing forms of

work that are defined

geographically, she firstly

notes the nature and, by

implication, the status of

two types of work:

There are

differences

[in

the

two forms of

work]

in

the

first place

work

in

the house

does not

pay

and work

outside the home pays.

She is conscious

that

only

the

work

located outside

of the home is rewarded monetarily

but that

there

are

no

such

rewards for

domestic work.

This,

as

I will

discuss shortly, is

not

only significant

for

financial concerns,

but

also

has

implications

for

women's sense

of

self-worth.

Mata

continues

on

to

argue

that there are no

inherent benefits derived

from domestic work either.

You

...

don't

enjoy [the

work]

in

the house as much as

work

[outside

of

it. I

wouldn't

want

to be a

housewife]

because

it would bore me to

be

in

the house all

day

always doing

the same

thing.

At

[paid]

work

at

least

you

have more

activities

[to

do].

This is

a

common

view amongst the younger re-

spondents. Mona, aged 21,

for

example, argues

that

if I

have to do the cleaning every day,

it

would

weigh

[me]

down.

All

afternoon

in the house alone would

bore me.

Nena, aged 33, argues: 'the way

I

see

it

is that

it

[housework]

is

very

routine or

it

is the same old

drag'.

Of the

respondents

aged between

19 and

33, only Nena,

who

is

married,

undertakes

responsibility

for

housework,

while the

others,

who are all still

living

in

the

parental

home

(at

the

time of

interview),

depend

on their mothers.

Moreover, only

Mata and Nena have experience of

paid

work.

Cristina, aged 38,

referred to

earlier,

has

experi-

ence of both domestic and

paid

work.

She is the

8/15/2019 Mohammad Cinderella Complex TIBG 2005

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/mohammad-cinderella-complex-tibg-2005 11/15

The

Cinderella

complex

only

postgraduate

amongst my

respondents

and

betrays a

greater

internalization of SSF

discourse.

While Mata,

Mona, Nena

and Yessica,

aged 25,

simply

point to the

routine

nature

and

dullness of

domestic work,

Cristina argues

that working

in

the

home is not only

always the

same [but] work in

the home is

[also]

mechanical.

Moreover work

in

the home

conditions

you.

How

can

I

explain? Work

in

the

house

conditions

your

psychic structure.

It

closes

your [mind].

Cristina's

views are

reiterated by

respondents

from

Violante and

Quintana's

(1992)

study. They

show how

the home is

experienced

by women as

a

container that hems them

in

within

its four

walls,

producing an

environment

that is

mentally stifling,

blocking personal

development.

Alongside the lack

of reward

promised by domestic

labour

undertaken in an

alienating

environment,

there is also a

third issue put

forward by

Violeta, a

feminist, working

within

the

municipal

state women's

office.

While she

acknowledges

that

today '[y]ou

can

opt to be a

housewife, you can

freely opt

to be

whatever you want',

she warns

that:

a

woman

who retains the

mentality, that

[even]

today

she can

remain within the

heart of the

home

dedicating

her self

only to

being

a

housewife, mother and

wife,

[she] perpetuates the situation

of

inequality

more and

more.

Why?

Because from

this perspective

you

are

not able

to demand the

sharing of tasks

within

the

house.

[So]

from this

perspective

she

[the

housewife]

is

limiting

[herself].

The woman

who limits

herself to the

house allows

herself to be

made a slave

to it. This

commonly

held view is

exemplified

by Yessica,

whose father

has

been

the breadwinner

while her

mother gave

up paid work to raise a

family of four sons

and a

daughter and

continues to

act as cook,

server

and

launderer to her

grown up

children,

including

married sons. Yessica declares:

I

am

clear

that

I

do not want

a life like my

mother

has

lived.

I

don't want to

be a slave of a

house.

In

the

end,

getting out of the house

serves

as an

escape

and

you

can

liberate

yourself

from

the problems that

you

have

in

the

house.

Thus,

a

release

from the

home enables women to

escape

an

alienating

environment and shed the

domestic

burden that

they have

hitherto undertaken

partly

because

it

was

their

given

role

in

society

and

partly

as a labour

of

love,

seduced

by

the

ideologies

of love and

romance.

257

Yet

in contrast

to young

women,

older

women,

particularly

those aged between

60

and

72,

who

as

wives

and mothers

have greater

experience

of

the

domestic

environment

as well as

paid work

in and

outside

of

the home,

rarely

speak about

the

home

as site of containment. Rather, they recall the

parental

and

marital home

as a

haven from poverty,

which articulated

with

state

repression

(Herr

1971;

Grugel

and Rees 1997)

during

the

early

post-Civil

War period

to generate

hardship

and

fear. Mdlaga

had been

resistant

to

the Nationalist

uprising

in

1936 and

remained

a republican

stronghold.

It

suffered

from

sustained

attack

by

the

Nationalists,

who

relied

on foreign

intervention

to

bring

it

down

(Barranquero

Texeira 1993).

Historian

Barranquero

Texeira points

out

how the

persecution

continued

after the Civil War when

groups

of

Falangistas

(fascist)

soldiers, [and]

the Civil

Guard

walked

the streets

and

it was not

difficult for

some

one to

shout 'he is

a red' so that they

would

be

immediately

detained. (1993,

217)

The

Civil Guard's

role

was to

weed out

any opp-

osition

to

General

Franco as

well

as other illegal

activity.

In these conditions

the home

provided

a

refuge.

Santana, aged

71,

recalls

for example

how:

My

father [was

involved

with]

the party,

the socialist

class that therewas, it again, seemed to me that he would

die,

because

he listened

to the

news

[on

the radio]

...

He

was

the first to have

a radio

and

the

people

of

Churriana [a

rural

locality

on the

outskirts

of

Malaga]

came

to

listen

to

it at

night

...

They

put

it in

a

small

room

that

we

had

at

the top,

because

the Civil Guard

[on

patrol]

used

to

come

at

night

and

any

one who had

a radio ...

would be

imprisoned.

My

father

and all the

other

men would

squeeze

into

this room

to

listen.

The

women

used

to

stay

below knitting

and whenever they

heard

beatings

or

noise, my

mother

would

say [to

us]

run

up.