Ind. zone 1

Transcript of Ind. zone 1

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

1/20

Journal of Environmental Management (2001) 61, 281300doi:10.1006/jema.2000.0413, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on

Industrial-waste management indeveloping countries: The case of

Lebanon

M. El-Fadel*, M. Zeinati, K. El-Jisr and D. Jamali

This paper presents a critical assessment of the existing Lebanese industrial sector, namely the current status and classification of industrial establishments based on a comparative synthesis and analysis ofrecent nationwide surveys and studies pertaining to industrial-waste management. Characterisation of solid and liquid industrial wastes generated, including hazardous wastes, is presented together with current and projected waste loads, recycling opportunities, and export/import practices. Institutional capacity andneeds pertaining to the enforcement of relevant environmental legislation, staffing and resources, monitoring

schemes, and public participation are critically evaluated. Finally, realistic options for industrial-wastemanagement in the context of country-specific institutional economic and technical limitations are outlined.The industrial sector in Lebanon consists of small-scale industries (84% employ less than 10 persons),

primarily involved in light manufacturing (96%). These industries which are distributed among 41 ill-defined zones and deficient in appropriate physical infrastructure, generate solid, liquid, and hazardous wasteestimated at 346730 tons/year, 20 169600 m3 /year and between 3000 to 15 000 tons/year, respectively.

Although the growth of this sector contributes significantly to the socio-economic development of thecountry (industry accounts for 17% of the gross domestic product), in the absence of a comprehensiveenvironmental management plan, this expansion may not be sustained into the coming millennium. The

anticipated expansion will inevitably amplify adverse environmental impacts associated with industrialactivities due to rising waste volumes and improper waste handling and disposal practices. These impactsare further aggravated by a deficient institutional framework, a lack of adequate environmental laws, and laxenforcement of regulations governing industrial-waste management.

2001 Academic Press

Keywords: industrial/hazardous-waste management, institutional framework, developingcountries, Lebanon.

Introduction

In the last decade the global economy hasundergone radical changes which have hadsignificant implications for the future devel-opment and operation of industrial estab-lishments, particularly in developing coun-tries. These changes include the move from

centrally planned economies into marketeconomies, the establishment of large eco-nomic blocks, liberalisation of internationaltrade and rapid advances in the fields of sci-ence and technology. These are further exem-plified through the introduction of the ISO14 000 standards for environmental control

Email of corresponding author: [email protected]

* Corresponding author

Department of Civil and

Environmental Engineering

Faculty of Engineering and

Architecture, AmericanUniversity of Beirut, Bliss

Street, P.O. Box 11-0236,

Beirut, Lebanon

Department of Social and

Public Policy, University of

Kent, Canterbury, UK

Received 17 November

1999; accepted 8

December 2000

as well as other total quality managementcontrol measures (ESCWA, 1996; UNIDO,1997). Furthermore, industrial reform poli-cies, in developing economies, tend to empha-sise accelerated industrialisation (UNIDO,1995b). The driving force behind this trend isthe realisation that greater socio-economicdevelopment including enhanced employ-

ment opportunities, higher incomes, and bet-ter standards of living can best be attainedthrough rapid industrial expansion (UNIDO,1995a).

In response to global changes, many coun-tries, especially developing economies, ini-tiated industrial restructuring programs topromote the private manufacturing sector.While new policies are being adopted and

03014797/01/040281C20 $35.00/0 2001 Academic Press

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

2/20

282 M. El-Fadel et al.

implemented by governments around theworld to face the challenges of the new inter-national environment, many countries haveyet to introduce changes of this sort.

Lebanon experienced nearly 2 decades ofcivil unrest (19751990), during which mostof the countrys physical infrastructure wasseverely damaged, especially electricity andtransmission lines, road networks, telecom-munications facilities and water supply andsewerage. Post-war reconstruction and devel-opment projects have focused on rehabili-tating and upgrading basic physical infras-tructure and enhancing the performance ofnational strategic sectors.

Reconstruction efforts were mainly finan-ced through regional and international loansand grants in addition to foreign invest-ment on a build operate transfer (BOT)basis. The industrial sector was of courseone of the beneficiaries, and its recovery has

been remarkable as evidenced by the factthat 30% of existing industrial units wereestablished between 1990 and 1994 (MoIP,1994). This trend is indicative of the vital-ity and resilience of this economic sector,which is expected to continue to exhibit astrong future growth. However, this initialrecovery remains shaky in view of nationalconstraints and regional instability. Indeed,the Lebanese industrial sector still suffersfrom inadequate planning, deficient physicalinfrastructure in certain areasparticularlyindustrial zoningand the absence of a com-

prehensive outlook concerning industrial-waste management. Current undertakings inwaste handling have mainly been directedtowards improving and upgrading munici-pal solid-waste management. The constraintsfaced in the collection, treatment and disposalof other waste types in addition to legislativeand institutional deficiencies remain issuesof concern (Tebodin, 1998b).

This paper evaluates the existing condi-tions of the industrial sector in Lebanonwith emphasis on various classificationsof industrial establishments. Characterisa-

tion of solid and liquid industrial/hazardouswastes is presented together with current andprojected waste loads. Institutional capac-ity and needs pertaining to the enforce-ment of relevant environmental legislation,staffing and training programs and monitor-ing schemes are critically evaluated. Finally,management options are evaluated taking

into consideration country-specific institu-tional, economic and technical limitations.

Sources of information

Several nationwide surveys and studies per-taining to industrial and hazardous waste

management in Lebanon have been con-ducted since 1990. A list of these surveysand studies with a synopsis of their principalobjectives and scope of work is presented inTable 1.

The first post-war nationwide industrialcensus (as outlined in Table 1) was completedin 1995 and was divided into two phases. Theobjective of the first phase, conducted in 1994,was to collect baseline data on the total num-ber of existing industrial establishments,their geographical localization, the number ofsalaried employees, their juridical form andnationality (MoIP, 1994). The second phasefocused on data related to production volume,employment, workforce salaries, added value,investments and stocks (MoIP, 1995). Laterstudies relied on this census to characteriseand estimate waste generation quantitiesand volumes (ERM, 1995a; Dar Al-Handasah,1996, 1997; Tebodin, 1998a,b). In 1996, theexisting legal framework pertaining to theclassification of industries was reviewed, andan improved framework was developed onthe basis of environmental and health zoning

categories (IDAL/FUGRO, 1996). However,this framework has not been implementedto date.

A recent characterisation and assessmentof the Lebanese coastal zone area includedan evaluation section on industrial impactson this zone (ECODIT-IAURIF, 1997). Also anational industrial waste-management planwas proposed in 1997 covering a wide range oftopics related to the industrial sector includ-ing, identification of existing sources, quan-tities, and volumes of various types of indus-trial waste through site visits; estimation of

current and projected waste loads; assess-ment of industry-related institutional struc-tures and methods for improving their capa-bilities (training and staffing requirements);drafting monitoring plans, and outlining thelegal and social implications of the proposedmanagement plan (Dar Al-Handasah, 1996,1997).

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

3/20

Industrial-waste management in developing countries 283

Table 1. Summary of recent industrial and hazardous-waste management surveys and studies in Lebanon

Reference Principal study objective/Scope of work

MoIP (1994) First nation wide census of Lebanese industry since 1970. Itsobjective was to determine the total number of existingindustrial establishments, their geographical localization,number of salaried employees, their juridical form andnationality

MoIP (1995) Collect data on: production volume, employment, workforce

salaries, added value, investments and stocksERM (1995a) Assess the state of the environment including a section covering

industrial activities and estimates of industrial-waste types andgeneration rate

Dar Al-Handasah (1996) Collect data for a national industrial-waste-management planIdentify existing sources of industrial-waste through site visitsCharacterize industrial-waste types, quantities and volumes

through a nationwide sampling of industrial companiesPropose a national monitoring plan for waste dischargeIdentify institutional structures related to industry and propose

methods for improving their capabilities

IDAL/FUGRO (1996) Update and improve the existing legal industrial classificationframework

Dar Al-Handasah (1997) Propose a national industrial-waste-management planEstimate current and projected waste loadsEstimate incurred costsDefine staff training and qualification requirements of responsible

authoritiesIdentify legal and social implications of proposed management

plan

ECODIT-IAURIF (1997) Assess environmental impacts along the Lebanese coast,including industrial zones

Provide recommendations for sustainable development of thecoastal zone by providing a basis for a future comprehensivecoastal zone management plan

ETEC (1998) Propose a national plan for the collection of used oilsRecommend collection methods and treatment optionsDefine socio-economic and environmental impacts of proposed

planERM and Issa Consulting (1998) Develop a strategy for the introduction and implementation of a

national hospital-waste-management plan including design oftreatment/disposal facilities and transport routes, andassessment of environmental impacts of proposed sites

Tebodin (1998a) Identify major industrial pollutants nationwide through site visitsto several industries in six industrial zones selected by theMinistry of Environment

Estimate industrial emissions into the atmosphere, water bodiesand the generation of hazardous solid wastes through the useof the World Banks Decision Support System (DSS) forIntegrated Pollution Control (IPC)

Tebodin (1998b) Estimate current and future industrial and hazardous wastevolumes

Identify treatment and disposal optionsEvaluate institutional structures and legislation related to industry

and present methods for improving their capabilitiesPropose strategies for a national industrial and hazardous-waste-

management scheme

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

4/20

284 M. El-Fadel et al.

The most recent study identified treatmentand disposal options for hazardous waste,including cost estimates, proper monitor-ing instruments, and an outline of anupdated legislative and institutional frame-work (Tebodin, 1998a,b). Note that hospitalrisk waste (ERM and Issa Consulting, 1998)and waste oil (ETEC, 1998) assessment stud-ies were conducted separately. Despite occa-sional shortcomings in the published data,the information provided in these surveysand studies provide the basis for designingand implementing a sound industrial-waste-management plan.

The studies and surveys were conductedfollowing various methodologies including:(1) census of country-wide industrial estab-lishments to gather basic background data;(2) distribution of standardised question-naires, primarily to establishments with arelatively large workforce (producing the

majority of the waste stream) to gather datapertaining to waste-management practices.Note that the samples were selected to berepresentative of different industry types andproportional to the distribution of industriesacross counties; (3) site reconnaissance vis-its and inspections of selected industries to

verify waste-management practices and vali-date estimates. Establishments were selectedfrom a list compiled by the Ministry ofEnvironment (MoE) or perceived to be themajor contributors of industrial-hazardous-waste generation based on responses to ques-

tionnaires; (4) interviews with managers ofindustrial establishments to assess waste-management practices; (5) sampling, test-ing, and analysis of selected waste sources,wastewater effluents, and gaseous emissionsat a limited number of industrial estab-lishments that were anticipated to producehazardous materials; (6) application of theWorld Banks Decision Support System forIntegrated Pollution Control (DSS IPC) toestimate industrial/hazardous-waste gener-ation and release into the atmosphere andwater bodies.

Characterisation of theindustrial sector

The industrial sector in Lebanon is charac-terised by small-scale establishments mainly

involved in manufacturing (96%) (MoIP,1994). The 19941995 national industrialcensus identified more than 22 100 opera-tional industrial establishments, employingapproximately 145 000 workers. The cen-sus did not cover publicly owned industriesincluding, those involved in power generationand distribution, storage of petroleum prod-ucts, potable water treatment and supply,telecommunications, and ports.

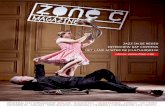

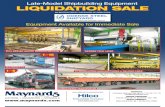

The establishments surveyed varied insize, from small backyard industrial com-panies employing less than five persons1 tolarger labour intensive industries employingmore than 250 workers2 (MoIP, 1994, 1995).These industries are distributed amongst41 zones within six counties (IDAL/FUGRO,1996) (Figure 1), and are generally clusteredaround major cities and towns. Heavy pri-mary industries are virtually absent from theLebanese industrial scene. Large-scale indus-

tries, characterised by a large work forceand output, include the cement plants, fer-tilizer factories and sugar refineries. Otherimportant segments of the industry sectorinclude food products and beverages (202%),furniture (163%), fabricated metal products(139%), wearing apparels and furs (136%),non-metallic mineral products (76%), andwood products (66%) (Figure 2).

Industrial establishments fall under oneof 24 subcategories based on the Interna-tional Standard Industrial Code (ISIC). Thelarge number of small-scale industrial com-

panies can be primarily attributed to thepreference of skilled labor to establish theirown low capital costs businesses due to thelow wage scale in the country (Dar Al Han-dasah, 1996). Note that approximately 65%of the industrial establishments are singleownership type (personal enterprises) withthe remaining of a general partnership type(MoIP, 1994).

It is evident from Figure 1 that the spatialdistribution of industrial zones varies acrosscounties with the counties of Mount Lebanon,Beirut and the North maintaining the high-

est number of industrial zones. The lowernumber in other counties can be attributed to

1 This category represents 68% of all existing industrialestablishments, rising to nearly 84% when consideringindustrial companies employing less than 10 personsand together employ a total of 553% of the workforce.2 This category represents only 02% of total industrialestablishments, but employs 109% of the workforce.

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

5/20

Industrial-waste management in developing countries 285

LakeHoms

Medit

errane

anSea

268280

86 72191

104

361

535

173 199 172283

215

636

382

684

41 113

270

517

218300 338

147

1442

17971761

1331

569 502

487

777

1000

458367

292

N

NorthLebanon

Bekka

MountLebanon

Syria

Qaroun Lake

Nabatieh

SouthLebanon

Food products and beverages

Furniture and other manufacture products

Wearing apparels, furs

Fabricated metal products, except machinery

Other non-metallic mineral products

Wood and wood products

10 0 10 Kilometers

5, 9.8

24, 45

3, 9

8, 18

1, 5.4

Beirut

0, 12.6

Figure 1. Distribution of industrial zones in Lebanon. County border ( ), Industrial zones: class A ( ),class B ( ), class C ( ), river ( ). Figures in boxes are (i) number of zones, (ii) percentage of industries.

their location near the southern internationalborders where political instability prevails.High industrial growth is expected in theseareas with the onset of a Middle East peaceagreement particularly that the counties of

Beirut and Mount Lebanon are relativelysaturated with limited land area left forfuture expansion. Note that no provisionswere made to allow for the establishmentof industrial zones in Beirut proper. Thisimplies little room for development or evenreplacement of any of the currently existingindustries in case of closure.

Classification of industries

In Lebanon, there are 209 types of estab-lishments classified into one of three classes

(Ministry of Environment, Lebanon, 1994).However, a new classification system, util-ising ISIC criteria, was recently proposedby the government (IDAL/FUGRO, 1996)to expand the existing classification systemfrom three to five classes based on relativedegrees of threat to the environment andpotential local disturbance. The new classes

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

6/20

286 M. El-Fadel et al.

Agriculture, hunting and forestry

5000

Construction work

Number of establishments

0 4000300020001000

Mining and quarryingFood and beverages

Tobacco products

Wearing apparelsTextiles

Leather productsWood and wood productsPulp and paper products

Printed matter and recorded mediaCoke and refined petroleum productsChemicals and manmade fibers

Rubber and plasticOther non-metallic minerals

Basic metalsFabricated metal productsMachinery and equipment

Electrical machinery productsRadio and communication equipment

Medical, optical, watches and clocks

Other transport equipmentFurniture and other goods

Motor vehicles and trailers

Figure 2. Distribution of industries sorted in accordance to the International Standard Industrial Codesubcategory classification.

Table 2. Current and proposed industrial classes

Proposed ISIC based Description Existing equivalentclassification Lebanese classes

1 Serious threat to the environment and health 12 Threat to the environment and health 13 Limited threat to the environment and health 24 Insignificant threat to the environment and health 35 No threat to the environment and health (in general) 3

IDAL/FUGRO (1996).

range from serious threat to the environment

and health to no threat. Table 2 pro-vides a comparative equivalency between thenewly proposed ISIC classification systemand the existing classes. Note that basedon the ISIC classification, only two typesof Lebanese industries would be classifiedas Class 1, namely refined petroleum prod-ucts, and pesticides or other agro-chemicalproducts (IDAL/FUGRO, 1996).

Based on the above classes, an evaluationsystem of industrial areas was developedconsisting of four areas denoted A-Area, B-area and C-area and Buffer Zones (Figure 1).

The criteria used for evaluation includedenvironmental, geographical, planning andeconomical aspects. Each area is reservedfor a given industrial class (Table 3). Thefourth area consists of buffer zones andis located within A, B and C areas andaround residential areas. In some cases,more than one class of industry may exist

in the same industrial area. For instance,

A-Areas are reserved for class 1 industries,however, class 2 industries may be allowedin these areas if class 1 industries do notcompletely occupy the available space. Thedrawback is that this may hinder futureexpansion of industry classes that wereoriginally designated for the area.

The majority of the industrial areas fallunder the C-Area class, which consists pri-marily of Class 3 industries that pose lim-ited threats to the environment and health(Figure 3). Based on industrial zone classifi-cation only one zone was classified as A-Area

(Figure 1).

Current and projectedindustrial waste loads

Estimates of industrial liquid effluents andsolid-waste loads are presented in the

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

7/20

Industrial-waste management in developing countries 287

Table 3. Proposed industrial area classification

Class Description

A-Area Reserved for Class 1 industries which can cause serious threat to theenvironment and/or serious disturbance to their surroundings. Class 2industries may be allowed in these areas if Class 1 industries cannot fillup the area

B-Area Reserved for Class 2 industries which can cause threat to the environmentor which can cause disturbance to their surroundings. Class 3 industriesmay be allowed in these areas if Class 2 industries do not fill up the area

C-Area Reserved for Class 3 industries which can cause no, or almost no, threat tothe environment or disturbance to its surroundings. In these areasClass 2 industries can be allowed if they are presently operating in thearea. New Class 2 industries must be located in A or B-Areas

Buffer Zones These buffer zones are located within A, B and C-Areas and aroundresidential areas or other sensitive locations

IDAL/FUGRO (1996).

A-area2%

C-area67%

B-area31%

Figure 3. Distribution of industrial areas accordingto class.

following section together with projectionsup to the year 2020. Hazardous-waste projec-tions are estimated separately.

Non-hazardous solid industrial

waste

In the absence of waste generation and pro-

duction statistics, the amount of solid wastegenerated was estimated using waste mul-tipliers based on employment statistics. Amean generation rate of 8 kg of industrialwaste per employee per day was used for alltypes of industrial facilities except for textilesand wearing apparels, for which a generationrate of 2 kg per employee per day was adopted

(Dar Al-Handasah, 1997). In contrast, indus-trial waste multipliers in several Europeancountries (Williams, 1998) range betweentwo to four times those used for Lebanon.Note that waste-generation multipliers will

vary depending on the type of industry, variations in manufacturing processes, andeconomies of scale (Rhyner and Green, 1998).Future industrial solid waste loads were pro-

jected assuming an industrial growth rateof 8% up to year 2000 and 5% for theperiod 20012020 (Table 4). Other importantassumptions include: (1) industrial employ-ment will reach 350 000 by the year 2020;(2) no new industries would be permittedwithin the City of Beirut; and (3) half of thenew industries would be located in Mount

Lebanon.Note that the assumption that futureindustrial-waste quantities increase linearlywith the degree of industrialisation tendsto overestimate future waste production. Itis reasonable to assume that the projectedquantities of waste produced may be signifi-cantly reduced with the introduction of newtechnology, waste minimisation schemes andinitiation of recycling and reuse of industrial-waste material. However, a quantification ofthis reduction is not possible in the absenceof relevant historical trends.

Non-hazardous liquid industrial

waste

In determining industrial wastewater flows,it was assumed that each employee con-tributes 300 l/day to the total flow (Dar

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

8/20

288 M. El-Fadel et al.

Table 4. Industrial solid waste loads

County Regional share of Industrial solid waste generatedindustrial employment (kg/day)a

1994 2020

Beirut 0121 110 073 110 073Bekaa 0065 69 693 883 883Mount Lebanon 0602 644 152 2 167 341Nabatiyeh 0025 27 262 46 847

North Lebanon 0129 137 848 720 756South Lebanon 0058 61 662 162 010

Total for entire country 1000 1 050 690 4 090 909

Dar Al-Handasah (1997).aGeneration rate of 8 kg of industrial waste per employee per day except for textiles and wearingapparels, for which a generation rate of 2 kg per employee per day was adopted.

Al-Handasah, 1997). Since actual wastewaterflow arising from industrial activities isnot directly proportional to the number ofemployees, existing and future wastewa-ter loads were estimated based on derived

water consumption rates for every indus-trial establishment, accounting for their sizeand type. Three size categories were used forthis paper:

Industry Number of employees

Light 100

Since a significant number of industriesadopt dry processes, generating minimalquantities of liquid waste, the estimation

of industrial wastewater loads consideredonly the proportion of the industries in eachsector that do generate liquid waste. Overall,the industrial wastewater flow for the entirecountry was reported to constitute 12% of thetotal estimated wastewater generated fromdomestic and commercial activities. Thiscontribution varies significantly according tocounty, due to varying densities of industrialzones. Hence, the contribution of industrialwastewater to total wastewater in 1994ranged between 3%, for the county of Beirutand Nabatieh, to 21% in Mount Lebanon. In

2020, this contribution is expected to rangebetween 1%, in Beirut, to 23% in the Bekaa(Table 5).

These projections are based on similarassumptions governing non-hazardous indus-trial solid-waste generation rates. Determin-ing the contribution of industrial wastewaterto the total wastewater stream is critical for

the selection of an adequate and cost effectivetreatment and disposal method. If co-disposalfollowing pretreatment at the source is therecommended option for industrial waste-water management, then industrial waste-

water must not exceed 1520% of the totalto ensure proper performance of treatmentfacilities (Dar Al-Handasah, 1997).

The volumes of solid and liquid wasteestimated above are not purely industrialin nature since the waste generation rateper worker per day (28 kg or 300 l for solidor liquid waste) includes waste categoriessimilar to municipal solid waste (MSW) suchas plastics, paper and cardboard, and glass.These projections are, however, valuable forestimating the contribution of industries tototal waste volumes.

An alternative method to estimate waste volumes relies on chemical and physicalcharacteristics distinct from MSW (Tebodin,1998b). In this context, industrial-waste cat-egories were identified as a function ofthe generation source or type of industry.Only four waste categories were proposedand they include hazardous waste, non-hazardous and/or recyclable waste, construc-tion and demolition waste and putrescentwaste. Derived volumes for each source andtype of waste were partly based on site visitsand questionnaires, and partly using existing

data from recent surveys (Tebodin, 1998a).The overall distribution of industrial waste

volumes using this method is presented inTable 6.

An estimated 188 850 tons of mediumto high impact waste are generated inLebanon each year. This is significantlyless than the total mixed industrial waste

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

9/20

Industrial-waste management in developing countries 289

Table 5. Industrial wastewater loads

County 1994 2020

Wastewater Industrial Wastewater Industrialgenerated wastewater generated wastewater

m3/d (percent of total) m3/d (percent of total)

Beirut 2754 3 2754 1Bekaa 5279 10 422 159 23Mount Lebanon 43 914 21 107 584 17Nabatieh 698 3 1479 2North Lebanon 6084 6 34 378 11South Lebanon 2391 6 3269 3

Totals for entire country 61 120 12 191 623 12

Dar Al-Handasah (1997).

Table 6. Current (1998) industrial waste-generation estimates

Category Source/type Quantity Remarks(ton/year)

Hazardous waste Pesticides manufacturing 326 Mainly packaging waste andsludge contaminated withpesticides

Industrial waste containing

heavy metals

1166 From waste paper recycling,

printing, ceramics industry(pigments), metalgalvanizing, non-ferrometal recycling

Industrial oily waste 1018 Residues from waste oilrecycling, oily sludge,residues from solventsrecycling

Industrial paints, resins,dyes, adhesive residues

538 Mainly from paint, andwooden and metalproducts manufacturing

Polychlorinated biphenols 40Tanneries 250 Hazardous due to chromium

contentNon-hazardous

waste orrecyclablewaste

Various process wastewith heavy metalcontents belowhazardous waste limits

1292 Scrap leather, wood andpaper waste, waste fromtextile, printing andferro-metal industry

Sludge fromasbestos/cementmanufacture

2400 Dumped at private landfills

Used lubricating oils 10 000End of life vehicles 6300 Recyclable partsEnd of life vehicles 700 Non-recyclables, this can be

hazardous waste,depending on the type ofcar dismantling

Industrial mixed waste(non-process related)

20000

Car tires 14 000Construction and

demolitionwaste

Ceramic industry (tiles,flags), cement industry

73000 Around 71 000 tons/year ofthis waste is dumped atprivate landfills (cementindustry)

Putrescent waste Food and beveragemanufacturing

17820

Slaughterhouses 40 000

Total 188 850

Tebodin (1998b).

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

10/20

290 M. El-Fadel et al.

volume, estimated at 347000 tons per year(Table 4). This difference provides someindication on the relative volumes of lowto high-impact industrial wastes (includinghazardous wastes) and the uncertainties inestimating accurate waste-generation quan-tities.

Hazardous waste

Accurate statistics on the quantities andtypes of hazardous wastes produced inLebanon are difficult to obtain. Reliablemethods for estimating quantities generatedare non-existent, except through comprehen-sive field surveys. In order to estimate thecurrent and forthcoming volumes of haz-ardous industrial waste, a tentative list ofpotentially hazardous industrial wastes gen-erated was compiled by Tebodin (1998a). Thelist included asbestos, acids, alkalis, organic

solvents, waste oils and tannery wastes. Annex III of the Basel Convention (UNEP,1999) specifies 14 different properties whichrender a material potentially hazardous;however, the most frequently reported andused characteristics in practice are explosiv-ity, flammability, corrosivity and reactivity(La Grega et al., 1994). In the absence of aclear national definition and primary data,hazardous waste generation in Lebanon wasestimated using three different methods:

Country Gross Domestic Product (GDP);

Employment statistics; DSS IPC model.

When GDP values are correlated to the indus-trial status of a country, it is suggestedthat hazardous waste generation would bein the order of 1000 tons per billion US$ GDPin developing countries; 2000 tons in newlyindustrialized countries; and approximately5000 tons in countries with developed indus-tries (World Bank, 1989). An inter-countrycomparison of hazardous waste generation

to GDP within the Organization of EconomicCooperation and Development (OECD) is pre-sented in Figure 4. For Lebanon, using US$10 billion GDP in 1996 (EIU, 1996), corre-sponding hazardous waste would be in theorder of 10 000 to 20 000 tons per year, theequivalent of 29 to 58% of total industrialsolid waste. The percent range of estimatedhazardous waste produced is comparable tosome OECD countries based on numbersreported by Petts and Eduljee (1994).

An average of 15 000 tons was adopted topromote a broad estimate of the amountof hazardous waste generated. This valuewas projected over the next 20 years usingthe same industrial growth rates previouslydefined to estimate industrial/hazardoussolid-waste generation. The resulting trendin hazardous-waste generation in Lebanonusing the GDP approach is shown inFigure 5.

The estimates in Figure 5 assume thatindustrial growth is proportional to indus-trialisation. This can be justified only forthe short-term because the market for

manufactured products in developing coun-tries results in continuous economic growth

Australia

0

10

G

enerationGDP(kg/US$1000)

57.23

Austria

USA

Belgium

Canada

Denmark

Finland

France

Germany

Greece

Iceland

Ireland

Italy

Japan

Luxembourg

Netherlands

NewZealand

Norway

Portugal

Spain

Sweden

Switzerland

Turkey

UK

6

4

2

8

Figure 4. Inter-country comparisons of hazardous-waste generation within the OECD (Yakowitz, 1993).The USA estimate includes large quantities of dilute wastewater not reported in other OECD countries.

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

11/20

Industrial-waste management in developing countries 291

0

80 000

Year

Hazardouswaste

(1000t

onsperyear)

60 000

40 000

20 000

1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

15 00022 040

28 100

35 900

45 800

58 500

Figure 5. Hazardous-waste generation based onthe GDP approach.

at elevated rates compared to developednations. Note that the highest industrial-growth rates are observed in companies thatwere the most pollution intensive (ESCAP,1994). In the long term sucha rate is expectedto diminish particularly as waste minimisa-tion strategies are adopted.

As an alternative, hazardous waste gener-

ation can be estimated using employmentstatistics (Dar Al-Handasah, 1997). Thisapproach yields an estimate of approximately16 900 tons of hazardous industrial waste,which is consistent with the value obtainedusing the GDP approximation. Current andfuture estimates for seven hazardous wastetypes based on existing industry types andemployment data are presented in Figure 6.

Finally, the DSS IPC model (World Bank,1998) was applied using a sample of 200

industries which produce significant quan-tities of industrial wastes (Tebodin, 1998b).The resulting volume of hazardous wastewas estimated at less than 3000 tons peryear (Table 7). This assessment, however,reflects only sources that can be collected andhandled separately, leading to an amountthat is significantly less than that estimatedthrough the previous two approaches.

At present, there are no provisions forthe separate collection of special waste aris-ing from households. As a consequence, thiswaste will be mixed with other municipalwaste and disposed of in municipal sani-tary landfills. With respect to hospital riskwaste, estimated at 4000 tons per year, a pro-posed management plan includes separatecollection, treatment and disposal techniques(ERM and Issa Consulting, 1998).

Management of industrial andhazardous waste

While industrial-waste management is apressing need in Lebanon, the bulk (morethan 90%) of wastes generated can be clas-sified as non-hazardous waste most of whichis similar to domestic municipal waste (Dar

Al-Handasah, 1997; Tebodin, 1998a). Indus-trial activities, which require special atten-tion from an environmental perspective, are

Figure 6. Estimated hazardous-waste generation based on industry types and employment data.1995, ; 2020, .

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

12/20

292 M. El-Fadel et al.

Table 7. DSS IPC Estimated hazardous-waste generation by source

Hazardous waste category 1998 quantity 2008 quantity 2020 quantity(ton/year) (ton/year) (ton/year)

Heavy metals 1166 1200 1482Oily waste 1018 1500 2652Paint, resins, dyes etc. 538 600 803Incineration residues 1478a 3252Waste water sludge 3171a 6976

Total 2722 7949 17 185

Tebodin (1998b).aBased on expected governmental plans for waste management options.

undertaken by cement production and man-ufacturing industries involved in metal prod-ucts, food processing, tanneries and textilefinishing (Tebodin, 1998b). Waste generatedfrom these activities is potentially hazardousdue to high sulfur and heavy metal (zinc,cadmium, mercury, chromium and copper)effluent content. As such, they require spe-

cial treatment and disposal techniques. Atpresent, most waste arising from the indus-trial sector is released into the surroundingatmosphere, discharged into adjacent waterbodies (rivers, streams, sea), stored on site,disposed of in privately owned landfills, incin-erated in the open, or dumped haphazardly(Dar Al-Handasah, 1997; ECODIT-IAURIF,1997; ERM, 1995a; Tebodin, 1998b). Suchpractices resulted in environmental stressesparticularly along the coastal zone wherethe industrial zones are spread (ECODIT-IAURIF, 1997; ERM, 1995a). The man-

agement of industrial waste faces severalconstraints typical of developing countries,including (ERM, 1995a,b):

the majority of the industry is small-scalein nature and fragmented all over thecountry leading to difficulties in collection,separation and proper disposal;

low awareness amongst waste generatorsabout environmental and health hazardsassociated with improper handling andexposure to certain wastes and their chem-ical constituents;

inadequate access to information on properwaste management and best availabletechnologies;

lack of enforcement of existing waste-management regulations;

cash stripped firms which are unlikelyto voluntarily invest in costly pollutionprevention and minimisation technologies

in the light of lax enforcement of legislationand lack of monetary or tax incentives;

absence of efficient and effective industrialinformation systems to support or guidepolicy and decision-making.

Recycling of industrial waste

Recycling and/or recovery practices for indus-trial liquid effluents or solid waste productsare currently not widespread in Lebanonand will not significantly alter or reducewaste loads within the next couple of decadesbecause of the absence of a market forrecyclable materials. At present, recyclingis limited to a few companies and is car-ried out on an ad hoc basis mainly in themetal processing, paper, plastic manufac-turing industries (Dar Al-Handasah, 1996).In addition, an estimated 2000 tons per

year of mineral waste oil or about 711%of total waste oil generated nation-wide,3

are recycled (Tebodin, 1998a) and approxi-mately 90% of the 7000 tons of lead acidbatteries discarded annually from vehiclesand uninterrupted-power-supply systems arerecycled (Tebodin, 1998b). Quantitative dataconcerning other recycled material are notavailable.

Import and export of industrial

waste

At present, Lebanon can be depicted as aclosed system with respect to the flow ofwaste. Export of waste is not practiced as

3 Plans for future expansion have been proposed for therecovery and reuse of waste oil (Arnaout, 1997; ETEC,1998).

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

13/20

Industrial-waste management in developing countries 293

most of the waste is not of a suitable qualityto be sold in the regional or internationalmarket as secondary waste material. Dur-ing the years of civil unrest, industrial andhazardous wastes were imported from sev-eral industrialised nations and improperlydisposed of throughout the country. Publiccondemnation resulted in re-exporting mostof this waste back to the countries of ori-gin. Moreover, recent regulations banned theimport of waste for the purpose of final dis-posal (Ministry of Environment, Lebanon,1997a,b). Nevertheless, importing waste oilfrom neighboring countries to be recycledin a centralized facility as part of a futurenational strategy for recovery and reuse ofwaste oil has been proposed (ETEC, 1998) toimprove economic sustainability of the wasteoil recovery plan. Furthermore, the genera-tion of pesticides and PCB related wastes arerelatively insignificant therefore it is more

economic to export such wastes for treatmentand disposal.

Legislative and institutionalframework

Lebanon has a substantial body of envi-ronmental related laws, however most dateback to the 1930s and are in need of updat-ing and consolidation (El-Fadel et al., 2000;ESCWA, 1999; ERM, 1995b). While exist-

ing environmental regulations are aimedat minimising nuisance and the protectionof public health, they are deficient withregards to standards pertaining to wastemanagement. In addition, existing standardsdeal primarily with domestic municipal solidwaste. While, there is a law related to haz-ardous materials (Lebanon, 1988), it lacksclarity in terms of waste classification and israrely applied. This law predates the 1989Basel Convention,4 which defines propertiesand tests for classifying materials as haz-ardous (UNEP, 1999) and as a consequence,does not conform to its classifications ordefinitions.

Deficient institutional support capabili-ties constitute a major limitation in most

4 Lebanon is a signatory to the Basel Convention andratified it on December 21, 1994. It became effective onMarch 3, 1995.

developing countries and must be enhancedas a prerequisite for private sector competi-tive growth (UNIDO, 1995a).A recent institu-tional reform effort in Lebanon culminated inthe creation of the Ministry of Environmentin 1993 (Ministry of Environment, Lebanon,1993), and contributed (at least conceptually)to strengthening the institutional capacityfor the design and implementation of sound

environmental policies. For example, a recentdecision, issued by the MoE, sets various air,soil, and water standards for the protection ofthe environment (Ministry of Environment,Lebanon, 1996).

Recent legislation

A national strategy for the management ofindustrial waste requires addressing legisla-tive deficiencies. A comprehensive national

Environmental Framework Law (EFL) iscurrently awaiting parliamentary approval.In addition to other provisions related toenvironmental protection and managementthe EFL includes sections on waste man-agement requirements. Specifically, the EFLconsists of 102 articles grouped into sevenmain divisions that will provide a legisla-tive framework for the subsequent draft-ing of individual decrees to shape thenational environmental management strat-egy. Unlike laws, decrees address environ-mental issues at the micro level, by set-

ting clear standards, guidelines and defin-ing permissible management practices. Theobjectives of relevant EFL decrees concern-ing waste management are summarised inTable 8.

Responsible authorities

The management of industrial activities inLebanon is the responsibility of the Ministryof Industry (MoI) which was created in 1997

(Ministry of Industry, Lebanon, 1997) andwas formerly a directorate general under theMinistry of Industry and Petroleum. Whilethe MoI is responsible for registering andlicensing industrial establishments in coor-dination with other ministries, it has noauthority to reject a license application foran industry (ERM, 1995a). Industrial waste

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

14/20

294 M. El-Fadel et al.

Table 8. Objectives of the EFL waste management related decrees

Decree Objective

Waste definitions andclassifications

To define waste categories and allow the differentiation betweenmunicipal and industrial/hazardous waste. Adoption of the BaselConvention definition since Lebanon must use this classification ininternational contacts

Integrated waste management To provide guidelines and rules for both private and publicorganizations dealing in waste-management activities: collection,transport, storage, sorting, reuse, treatment and disposal

To identify permit requirements for various types of wastemanagement firms (collection, transport, storage, treatment ordisposal)

To limit the number of waste treatment companiesProduct legislation To regulate and ban the use of specific materials or substances that

complicate waste treatmentNational fund for environmental

protectionTo support investment in cleaner production technologies, waste

recycling and treatment methodologiesTo incorporate clearly defined tasks, project identification

procedures, conditions and managementStandards for atmospheric To ensure that industrial wastes are disposed of properly

emissions, wastewater effluents, To account for a comprehensive waste-management programwater and soil protection especially for the hazardous waste generating industry

EIA and permitting To adopt the polluter pays principleMonitoring and enforcement To set high/severe levels to deter infringement

Fines and sanctions

management on the other hand, falls withinthe scope of the Ministry of Environment,although the main executive institution isthe Ministry of Interior (Dar Al-Handasah,1997). Other ministries and public agencieshave industrial-waste-management respon-sibilities, resulting in the fragmentation ofauthority and low level of accountability.Table 9 depicts a matrix for the role of

various ministries and public authorities inindustrial-waste management. It illustratesfunctional gaps and the overlap in responsi-bilities.

Despite the apparent attempt at integrat-ing the environmental management systemunder a separate environmental protectionministry (MoE) with independent adminis-trative functions and resources, the insti-tutional framework for environmental man-agement remains fragmented and weak.This is because the MoEs broad mandaterelating to environmental issues5 overlaps

with those of a number of other ministries

5 Including the power to: (1) formulate general environ-mental policy and propose measures for its implemen-tation in coordination with other concerned agencies;(2) protect the natural and man-made environment inthe interest of public health and welfare; and (3) con-trol and prevent pollution, irrespective of the source,(Ministry of the Environment, Lebanon, 1993, 1997c).

or governmental agencies as depicted inTable 9.

Resources and staffing

Low levels of technical and managerial capa-bilities constitute a major limitation in mostdeveloping countries (UNIDO, 1995c). In thiscontext, Lebanon is no exception as the avail-

able resources6

and staffing7

levels are suchthat the MoEs capacity for environmentalmanagement is very limited (World Bank,1996). The low salaries offered in the pub-lic sector in general, do not help in main-taining motivated inspectors which restrictsthe Ministrys ability to have a real impacton the coordination of various sector initia-tives and on facilitating the integration andenforcement of environmental laws and poli-cies (ERM, 1995b). As such, the MoE lacksprovisions for an environmental monitoringand enforcement unit with an acute shortage

of qualified technical personnel who can con-duct monitoring operations associated withwaste management.

6Annual budget of US$ 5 million in 1995 reduced to lessthan US$ 2 million in 1999.7 Thirty-eight full-time employees out of 139 specified bylaw and an unspecified number of contractors dependingon budget and grant availability.

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

15/20

Industrial-waste management in developing countries 295

Table 9. Industrial-waste-management matrix

Functiona MoE MoI Interior Public Finance Labor IDALb LIBNORc Munici Directoratehealth and Social -palities of urban

affairs planningd

Policy setting X XLicensing procedures O O O O O OHealth/safety

Public health protection O Occupational safety O

Monitoring O X XClassification

Industry type X O OLand use/industrial O O

zonesWaste disposal O X

managementProduct quality control OLegislation

Regulation and codes O OStandard setting Waste definition X

Enforcement XInvestment O

encouragement

Introduction of X O Xtechnology

aLevel of implementation of function: medium (), low (O), non-existent (X).bInvestment Development Authority of Lebanon, is an independent public authority.cLIBNOR (Lebanese Norms and Standards Institution) operates under the tutelage of the MoI.dThe directorate functions under the Ministry of Public Works.

Environmental monitoring

Monitoring is an essential part of develop-mental activities to ensure environmentalprotection. Monitoring data provide a use-ful tool for raising public awareness andcan even be used as the basis for a public-alert system in environmental-managementschemes. Such a system relies on a monitor-ing network to alert the responsible authoritywhen levels of pollution come to be per-ceived as having serious health effects. InLebanon, environmental monitoring is stillin its infancy and replicable methods forevaluating environmental stresses are stilldeficient, which is typical of most develop-ing countries. This is attributed to intensiveresource requirements, as well as high capi-

tal, operational and maintenance costs asso-ciated with environmental monitoring. Giventhe limited human and financial capacity ofthe MoE, comprehensive environmental mon-itoring to environmental release standards isnot foreseen in the near future. This impliesthat there is a need to insure that the imple-mented strategies are financially sustainable

in addition to being environmentally sound.If funds can be raised for specific areas ofimplementation then these assets can bemobilised to secure both human and tech-nical resources to implement the requiredmitigation measures and policies. Munici-

palities in coordination with the MoE canimplement these activities with the over-all responsibility for monitoring under thelatter. In addition, there is a potential forincreasing the involvement of private sectorassociations, institutions, and NGOs in envi-ronmental management (ERM, 1995b; WorldBank, 1996). This involvement may promotesustainability, but it is likely to remain defi-cient in the absence of proper institutionalsupport mechanisms (UNIDO, 1995b).

Public participation,

Non-governmental organisations,

and information dissemination

Education and information disseminationplay an important role in changing the publicperception concerning proper environmental

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

16/20

296 M. El-Fadel et al.

management. Environmental education is vital to raise the overall level of aware-ness and mobilise public opinion when alocal community is faced with a pollut-ing industry. At times, the most effectiveway to deal with polluting industries thatescape governmental control is to mount anaggressive campaign involving the local com-munity and the media to force industriesinto compliance. Non-Governmental Orga-nizations (NGOs) can play a vital role inbringing flagrant violations to the attentionof responsible authorities (ERM, 1995b). Dur-ing the last decade about 65 environmentalNGOs were created in Lebanon (ESCWA,1999); many are involved in raising aware-ness on current environmental issues, expos-ing environmental threats, protecting nat-ural reserves and habitats, and preventingexcessive pollution. In addition, a few inter-national NGOs have established offices in the

country and coordinate efforts and activitieswith their local counterparts.

Discussion and Conclusion

The industrial sector in Lebanon is rel-atively small with 84% of all industrialunits employing less than 10 workers.More than 22 000 industrial establishmentsgenerate a heterogeneous stream of no-impact, low and high impact substances.

An estimated 347 000 tons of solid waste,20169600m3 /year of liquid waste and bet-ween 3000 and 16 000 tons of hazardouswaste are generated annually from 41 poorlydelineated industrial zones and currentlydisposed of without any control measures.Country-specific options for industrial-wastemanagement require pre-treatment at sourcefor the majority of industrial waste effluentsand secured landfilling for hazardous waste.Waste minimisation technologies should beadopted and industry owners and managersencouraged to initiate material recycling and

reuse. While the development and construc-tion of waste treatment and disposal facilitiesis essential to manage the waste generated,it is imperative to address the necessaryinstitutional needs and introduce effectivelegislation with proper standards for environ-mental protection and pollution prevention.The systematic enforcement of regulations

and policies is also crucial to the success ofindustrial-waste management. Sound moni-toring practices are necessary to ensure thatfuture regulations are developed on the basisof accurate data and waste trends.

Management options

In assessing management options, it isimportant to note that neither the gov-ernment nor the industries are able toimmediately introduce and sustain radi-cal changes which necessarily entail highinvestment costs. While the post-war recon-struction drive has burdened the Lebanesegovernment and its resources, the major-ity of industries still face numerous obsta-cles that impede production. Despite theexistence of various technologies that can

mitigate and reduce environmental impactsassociated with industrial wastes (both atthe source of generation or at a centralwaste-treatment facility), their implementa-tion requires financial resources that existingsmall and medium scale industries cannotafford. Imposing additional financial burdenswill inevitably marginalise the industriesfurther. However, newly established indus-trial companies that utilise more advancedtechnology can implement pollution controland waste minimisation options. Technicalmanagement practices should therefore aimat reducing pollutant levels sufficiently toachieve compliance standards. Fortunately,the bulk of industrial waste in Lebanonrequires only minimal treatment to renderit adequate for regular disposal. Therefore,the most cost effective waste-managementstrategy should be based on pre-treatmentat the source followed by proper disposal(engineered landfill for solid wastes and co-disposal with municipal wastewater for liquideffluents). Pre-treatment options based onpollutant type and characteristics are well

established (WEF, 1994; LaGrega et al.,1994).

Following pre-treatment of waste, the pre-ferred treatment/disposal option will dependon the volume and composition of waste,environmental standards (Williams, 1998) aswell as the availability of adequate tech-nical and financial resources. Hazardous

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

17/20

Industrial-waste management in developing countries 297

Table

10.

Preferredwaste-treatment/disposaloptions

Treatment/disposaloption

Wastecategory

Typeofwas

te

Approximatequantity(1998)

Feasibility/limitation

Landfilling

Hazardouswaste

Wastecontainingheavymetals

1166

Cheapandfeasible

Industriallyoilywaste

1018

lowavailabilityinurbanareas

Industrialpaint,resins,dyes

,residues

538

Incinerationflyashandbottomslag

Notquantified

Industrialwastewatersludge

Notquantified

Incineration

Infectiouswaste

Hospitalwaste

4000

Expensive

co

mbustibles

Cartires

14000

Lackoftechnicalexpertise

Publicopposition

Economyofscale

Export

Hazardouswaste

Pesticides

326

Expensive

PCB

40

Co-disposalwithMSW

Non-hazardouswaste

Lowheavymetalcontentwaste

1290

Cheapandfeasible

Industrialmixedwaste

20000

Increasedgenerationofhighstrength

Wastewatersludge

Notquantified

leachate

Endoflifevehicle

700

Specialhouseholdwaste

3000

On-sitestorage

As

bestoswaste

Sludgefromasbestos/ceme

ntmanufacturing

2400

Limitedcapacity

Non-hazardouswaste

Ceramic/cementindustrywaste

73000

Phosphoricacidgypsum

Recyclingschemes

Recyclablewaste

Usedlubricatingoils

10000

Economyofscale

Endoflifevehicles

6300

Lackoftechnicalexpertise

Industrialrecyclablepackag

ingwaste

Notquantified

Agriculturalapplications

Pu

trescentwaste

Foodandbeverageproduction

32000

Cheapandfeasible

Municipalwastewatersludg

e

80000

Healthimpacts

Industrialwastewatersludge

6000

Soildegradation

ModifiedfromTebodin,1998b.

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

18/20

298 M. El-Fadel et al.

waste requires separate treatment, han-dling and disposal methods. In this con-text, several treatment and disposal optionscan be considered simultaneously, includ-ing reuse and recycling; physical, chemicalor biological treatment; landfilling, incinera-tion and export (World Bank, 1989; Freeman,1998). A synopsis of country-specific pre-ferred treatment-disposal alternatives under

current economic conditions is presented inTable 10.

Institutional considerations

Evolving the necessary institutional infra-structure encompasses a wide range ofrequirements including: (1) appropriate finan-cial services; (2) training facilities; (3) devel-opment of quality standards; (4) industrialinformation systems; (5) promotion of invest-ment and technology inflow; and (6) research

and development (UNIDO, 1995b). Thegrowth and expansion of small and mediumindustries, particularly in developing coun-tries, is largely dependent on the availabilityof proper institutional support and financialresources (UNIDO, 1995a). Moreover, theestablishment of clear institutional respon-sibilities is essential to ensure the effectiveimplementation of policies and reduce thepotential for conflicts of interest. It is notpossible to develop an operational waste-management system and recover incurred

costs in the absence of a proper institu-tional setup (Tebodin, 1998b). This involvesa dramatic reform in the current institu-tional setup, and introducing appropriatere-organisation and regulations. This seemsto be unacceptable to many policy-makers,particularly in developing countries, whererigid social, cultural, political and economicstructures prevail (ESCWA, 1996). Figure 7depicts a proposed framework for waste man-agement taking into consideration existingcountry-specific institutional characteristics.

The MoE would be the natural entityto assume the responsibility in initiatingand executing proposed actions of a waste-management plan. This will require theunfailing cooperation and support of theother ministries in drafting, implementingand enforcing the decrees within the Envi-ronmental Framework Law. Although it isevident that a grace period will be requiredfor existing industrial establishments to com-ply with proposed environmental standards,the imposition of punitive measures on law-breakers should be enforced as a deterrent tofuture violations.

Acknowledgements

Nationwide surveys and studies on industrialwaste management in Lebanon were funded by theMediterranean Environmental Technical Assis-tance Program (METAP), World Bank, German

Ministries of Public Health/Labor

Protect public health/safety

Ministry of Industry

Devise a national industrial management strategy

Simplify industrial permitting requirements

Implement industrial information management systems

Monitor industrial establishments

Environmental education/awareness

Ministry of Environment

Propose national environmental policy

Municipalities/Governorates

Licensing requirements

Update waste-management legislation

Environmental monitoring

Set standards (air quality, wastewater effluent, water, soil)

Set clear definitions for waste types and hazardous materials

Establish proper waste disposal methods/techniques

Require EIA procedures in industrial licensing

Promote waste minimisation and recycling

Environmental education/awareness

Environmental monitoring

Ministry of InteriorEnforce legislation and regulations

NGOs/public

Environmental monitoring/education

IDAL/Directorate of Urban Planning

Industry type classification

Land use zoning for industry

Figure 7. Proposed inter-relation of institutions in industrial-waste management.

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

19/20

Industrial-waste management in developing countries 299

Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) and theEuropean Commission.

References

Arnaout, S. (1997). Options for Vehicle WasteOil Management in Lebanon. Transtec/FitchnerConsortium, Ministry of Environment. Beirut,Lebanon.

Dar Al-Handasah. (1996). National IndustrialWaste Management Plan. Phase I Report: Prepa-ration of the National Industrial Waste Manage-ment Plan. Volume 1: Main Report. Ministry ofEnvironment. Beirut, Lebanon.

Dar Al-Handasah. (1997). National IndustrialWaste Management Plan. Phase II Report:

Preparation of the National Industrial Wastemanagement Plan. Volume 1: Main Report.Ministry of Environment. Beirut, Lebanon.

ECODIT-IAURIF (1997). Regional Environmen-tal Assessment Report on the Coastal Zone of

Lebanon. Final Report to Council for Develop-ment and Reconstruction. Beirut, Lebanon.

El-Fadel, M., Zeinati, M. and Jamali, D. (2000).Framework for environmental impact assess-ment in Lebanon.Environmental Impact Assess-ment Review 20, 579604.

Economic and Social Commission for West Asia(ESCWA) (1996). Industrial Strategies and Poli-cies in theESCWA Regionwithin the Contextof aChanging International and Regional Environ-ment. (E/ESCWA/ID/1995/7). New York: UnitedNations.

Economic and Social Commission for West Asia(ESCWA) (1999). Evaluation of the Adequacy of

Environmental Legislation and StrengtheningImplementation Methods in the ESCWA region.(E/ESCWA/ENR/1999/5). New York: United

Nations.Economic and Social Commission for Asia and thePacific (ESCAP) (1994). Manual for HazardousWaste Management, 2 vols. New York: UnitedNations.

Environmental Resources Management (ERM)(1995a). Lebanon: Assessment of the State of the

Environment. Ministry of Environment. Beirut,Lebanon.

Environmental Resources Management (ERM)(1995b). Lebanon: Identification of Policy Opti-ons. Ministry of Environment. Beirut, Lebanon.

Environmental Resources Management (ERM)and Issa Consulting. (1998). Feasibility Study

for the Collection and Treatment of HospitalWaste. Council for Development and Reconstruc-tion. Beirut, Lebanon.

European Intelligence Unit (EIU) (1996). CountryProfile, Lebanon 19961997. London: EIU.

Etudes Techniques (ETEC) (1998). Plan Directeurde la Gestion et de la Collecte des HuilesUsagees: Recommendations des Modes de Col-lecte et M ethodes de Traitement, Impact Socio-Economique et Environnemental du Plan Natio-

nal. Ministry of Environment. Beirut, Lebanon.

Freeman, H. (ed.) (1998). Standard Handbook ofHazardous Waste Treatment and Disposal, 2ndedn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Investment Development Authority of Lebanon(IDAL) and FUGRO (1996). Classification of

Industries and Industrial Zones. Beirut, Leba-non: IDAL.

LaGrega, M., Buckingham, P. and Evans, J.(1994). Hazardous Waste Management. New

York: McGraw Hill.

Lebanon (1988). Law Number 64 Dated 12 August1988, Protection of the Environment Against Pollution From Hazardous Waste and ToxicSubstances. Official Gazette. Beirut, Lebanon.

Ministry of Environment, Lebanon (1993). Law Number 216 Dated 3 April 1993, Creation ofthe Ministry of Environment. Official Gazette,Beirut, Lebanon.

Ministry of Environment, Lebanon (1994). Decree 4917 Dated 24 March 1994, Amendment of Decree 21 of 1932, The Classification of Haz-ardous, Detrimental to Health and NuisanceCausing Establishments. Official Gazette,Beirut, Lebanon.

Ministry of Environment, Lebanon (1996). Deci-sion 52/1 Dated 29 July 1996, Standards and

Limits for the Prevention of Air Water and SoilPollution. Official Gazette, Beirut, Lebanon.

Ministry of Environment, Lebanon (1997a). Deci-sion 71/1 Dated 19 May 1997, Organizationof Waste Importation. Official Gazette, Beirut,Lebanon.

Ministry of Environment, Lebanon (1997b). Deci-sion 161/1 Dated 31 October 1997, Amend-ment of Decision 71/1 of 19 May 1997. OfficialGazette, Beirut, Lebanon.

Ministry of Environment, Lebanon (1997c). Law667 Dated 27 December 1997, Amendment of

Law 216 Dated 3 April 1993 Pertaining to theCreation of the Ministry of Environment. OfficialGazette, Beirut, Lebanon.

Ministry of Industry, Lebanon (1997). Law 642 Dated 2 June 1997, Creation of the Ministry ofIndustry. Official Gazette, Beirut, Lebanon.

Ministry of Industry and Petroleum (MoIP) (1994).Report on Industrial Census, First and Prelimi-nary Phase. Ministry of Industry and Petroleum,Directorate of Industry. Beirut, Lebanon.

Ministry of Industry and Petroleum (MoIP) (1995). Report on Industrial Census, Phase II: FinalResults. Ministry of Industry and Petroleum,Directorate of Industry. Beirut, Lebanon.

Petts, J. and Eduljee, G. (1994). Environmental Impact Assessment for Waste Treatment and Disposal Facilities. Chichester: John Wiley andSons.

Rhyner, C. R. and Green, B. D. (1988). Thepredictive accuracy of published solid wastegeneration factors. Waste Management and

Research 6, 329338.Tebodin (1998a). Industrial Pollution Control,

Lebanon. The World Bank, UNIDO, Ministryof Environment. Beirut, Lebanon.

Tebodin (1998b). Industrial and Hazardous WasteManagement Strategy for Lebanon. Ministry ofEnvironment. Beirut, Lebanon.

-

8/3/2019 Ind. zone 1

20/20

300 M. El-Fadel et al.

United Nations Environment Program (UNEP)(1999). Basel Convention on the Control ofTransboundary Movement of Hazardous Wasteand Their Disposal (with Amended Annex Iand Two Additional Annexes VIII and IX,

Adopted at the Fourth Meeting of the Conferenceof Parties in 1998). Secretariat of the BaselConvention No. 99/001. New York: UnitedNations.

United Nations Industrial Development Orga-

nization (UNIDO) (1995a). Industrial Policy Reforms: The Changing Role of Governmentsand Private Sector Development. Backgroundpaper. UNIDO Secretariat, ID/WG.542/21(SPEC.)

United Nations Industrial Development Organi-zation (UNIDO) (1995b). Recent Industrial Poli-cies in Developing Countries and Economies inTransition: Trends and Impacts. Backgroundpaper prepared by Katherin Marton, UNIDO,ID/WG.542/22 (SPEC.)

United Nations Industrial Development Orga-nization (UNIDO) (1995). Governments and

Industrialization: The Role of Policy Interven-tion. Background paper prepared by SanjayaLall, UNIDO, ID/WG.542/23 (SPEC.)

United Nations Industrial Development Orga-nization (UNIDO) (1997). Country Support

Strategy: Lebanon. Arab Countries Bureau.Vienna: UNIDO.

Yakowitz, H. (1993). Waste management: whatnow? What next? An overview of policies andpractices in the OECD area. Resources, Conser-vation and Recycling 8, 131178.

Water Environment Federation (WEF) (1994). Pretreatment of Industrial Wastes, Manual ofPractice No. FD-3. Alexandria, Virginia: WaterEnvironment Federation.

Williams, P. (1998). Waste Treatment and Dis-posal. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.World Bank (1989). The Safe Disposal of Haz-

ardous Wastes. The Special Needs and Prob-lems of Developing Countries, 3 vols. (R. Bat-stone, J. Smith and D. Wilson eds). Techni-cal Paper Number 93. Washington DC: WorldBank.

World Bank (1996). Lebanon: Environmental Strategy Framework Paper. Natural Resources,Water and Environment Division, Middle EastDepartment, Middle East and North AfricaRegion. Washington DC: World Bank.

World Bank (1998). Decision Support System forIntegrated Pollution Control. Software for Edu-cation and Analysis in Pollution Management.

User Guide. Environment Department, Wash-ington DC: World Bank.