Hoofdartikel Judicial Psychology Serie De fusie van ...Hoofdartikel Judicial Psychology Serie De...

Transcript of Hoofdartikel Judicial Psychology Serie De fusie van ...Hoofdartikel Judicial Psychology Serie De...

Hoofdartikel Judicial PsychologySerie De fusie van gerechtshoven (deel 2)

rechtstreeks 2012 - nr 2

Recent verschenen

2012 – nr 1 De ProeftuinDe fusie van gerechtshoven (deel 1)

2011 – nr 4 Sharia(&)rechtspraak:rechtsontwikkelingen in de moslimwereld & Nederland

2011 – nr 3 Blind vertrouwen:de norm van rechterlijke integriteit

rechtstreeks 2012 nr 2

Raad voor derechtspraak

omslag rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:46 Pagina 1

omslag rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:46 Pagina 2

Judicial Psychology

De fusie van gerechtshoven (deel 2)Ontmoeting van bedrijfskundige concepten met de fuserendegerechtshoven

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 1

rechtstreeks 2/2012

2

RedactieProf. mr. J.D.A. (Hans) den Tonkelaar Vice-president rechtbank ArnhemHoogleraar Rechtspraak Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen

Dr. S. (Suzan) VerberkAdviseur wetenschappelijk onderzoek Raad voor derechtspraak

RedactieadresRedactie RechtstreeksRaad voor de rechtspraakAfd. OntwikkelingPostbus 906132509 LP Den HaagE-mail: [email protected]

UitgeverSdu Uitgevers bv, Den Haag

Oplage4650 exemplaren

ISSN 1573-5322

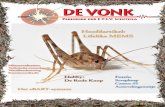

OmslagbeeldDe foto's op het omslag zijn overgenomen vanStock.XCHNG en raadpleegbaar op www.sxc.hu.

AbonnementenRechtstreeks wordt gratis toegezonden aan hen die totde doelgroep behoren. Wie meent voor toezending inaanmerking te komen wordt verzocht zijn naam, post-adres en functie kenbaar te maken aan het secre ta riaat vanRechtstreeks (rechtstreeks@recht spraak.nl).

AdresmutatiesSdu KlantenservicePostbus 200142500 EA Den Haagtel. 070-3789880of via: www.sdu.nl/service

RetourenBij onjuiste adressering verzoeken wij u gebruik temaken van de adresdrager en daarop de reden van retournering aan te geven.

© Staat der Nederlanden(Raad voor de rechtspraak)Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, ineen voor anderen toegankelijk gegevensbestand wordenopgeslagen of worden openbaar gemaakt zonder voor-afgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de Raad voorde rechtspraak. De toestemming wordt hierbij verleendvoor het verveelvoudigen, in een gegevensbestand toegankelijk maken of openbaar maken waarvoor geengeldelijke of andere tegenprestatie wordt gevraagd enontvangen en waarbij deze uitgave als bron wordt vermeld.

Colofon

Rechtstreeks is een periodiek van de Raad voor de rechtspraak en richt zich op de praktijk ende ontwikkeling van de rechtspraak in Nederland. Het blad stelt zich ten doel wetenschap-pelijke inzichten en bijdragen aan het publieke debat over de rechtspraak ter kennis te brengen van allen die beroepshalve bij de rechtspraak betrokken zijn. Opname in Rechtstreeksbetekent niet dat de inhoud het standpunt van de Raad voor de rechtspraak weergeeft.

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 2

3

Inhoud

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Inhoud

Redactioneel / 5

Over de auteurs / 7

Column Justitia / 9Alex Brenninkmeijer

Beschouwing Inleiding op ‘Judicial psychology’ van J.J. Rachlinski / 11Eric Rassin

Hoofdartikel Judicial Psychology / 15Jeffrey J. Rachlinski

Serie De fusie van gerechtshoven (deel 2)Ontmoeting van bedrijfskundige concepten met de fuserende gerechtshoven / 35Leny de Groot-van Leeuwen en Hans den Tonkelaar

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 3

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 4

Rechters, het zijn net mensen. Dat leertalthans het Engelstalige hoofdartikel van dehand van Jeffrey J. Rachlinski. Rachlinski iseen sociaal psycholoog verbonden aan deCornell Law School en de Erasmus Univer-siteit Rotterdam, waarbij hij de rechtspraakals belangrijk onderzoeksveld heeft gekozen.Op 8 december jongstleden gaf hij een presentatie over de psychologische val -kuilen bij rechterlijk besluitvormingsgedragtijdens ‘De dag van het oordeel’, eengeslaagde bijeenkomst georganiseerd doorde SSR en de Raad voor de rechtspraak.Gelet op het enthousiasme onder de aan -wezigen, vroegen zijn inzichten eromgedeeld te worden met een groter rechterlijkpubliek. Rechtstreeks leek ons daartoe hetmedium bij uitstek.

Het hoofdartikel vormt een weerslag van deinzichten die Rachlinski en zijn collega’s deafgelopen jaren hebben opgedaan over dedenkfouten waaraan ook rechters niet blijkente ontkomen. Maar wie denkt dat JudicialPsychology van Jeffrey J. Rachlinski zichver van huis afspeelt en over leuke hersen-brekertjes gaat, heeft het mis. Twee rede-neermethoden staan in het artikel centraal:een die is gebaseerd op intuïtieve kennis eneen gebaseerd op zuiver rationele kennis.Beide wijzen van redeneren, zo wordt aande hand van onderzoeksresultaten betoogd,

raken direct het rechterlijk werk. Ook hetwerk van de Nederlandse rechter!

Eric Rassin heeft zijn essay opgezet als kritische inleiding op het lezen van Rachlinski’s artikel. ‘Als jurist kan ik mevoorstellen,’ schrijft hij, ‘dat de lezer eendrempel ervaart als het gaat om een Engels-talig stuk waarin centraal staat dat er vanalles fout gaat tijdens het werk.’ En ver -volgens legt hij uit waarom Rachlinski tochgelezen moet worden. Als redactie sluitenwij ons hierbij aan. Daarbij merken wij nogop dat zowel Rassin als Rachlinski voor-beelden aan het strafrecht ontlenen, maardat de inzichten die hieraan kunnen wordenverbonden, even zo relevant zijn voorbestuurs- als civiele rechters.

In het tweede deel van de reeks over de fusievan gerechtshoven Leeuwarden en Arnhempassen Leny de Groot-van Leeuwen enHans den Tonkelaar de kernbegrippen, diein het vorige nummer door Allard van Rielgeïntroduceerd werden, toe op de situatievan de beide hoven. Ondanks gesignaleerdeverschuivingen in doelstellingen en accen-ten bij de behandeling van de HerzieningGerechtelijke Kaart in het parlement en hetvoortdurend aanwezige risico van bezuini-gingen, vormt het startpunt van dit artikelde genuanceerd-optimistische visie van de

rechtstreeks 2/2012 redactioneel

5

Redactioneel

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 5

hofpresidenten. Zij zien de fusie vooral alseen window of opportunity. De mogelijk -heden die de fusie biedt, worden in het artikel belicht.

Maar dit nummer opent met een columnvan Nationale Ombudsman Alex Brennink-meijer. Lichtvoetig geschreven, beeldendook, waar de departementale Justitia, deklassieke Justitia van het NOS-journaal enhet vignet van de Rechtspraak aan de ordekomen, maar ernstig waar de Rechtspraakop haar verantwoordelijkheid in onze maat-schappij wordt aangesproken. Brennink -meijer geeft het stokje door aan Kees vanden Bos. Van hen beiden verscheen onlangs,in NJB 2012, 21, het artikel ‘Vertrouwen inwetgeving, de overheid en de rechtspraak.De mens als informatieverwerkend individu’. En met deze laatste woorden is decirkel van deze nieuwe aflevering rond.

Hans den Tonkelaar Suzan Verberk

rechtstreeks 2/2012 redactioneel

6

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 6

Over de auteurs

Alex BrenninkmeijerDr. A.F.M. Brenninkmeijer is per 1 oktober 2005 en voor een tweede termijn ingaande 1 oktober 2011 door de Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal benoemd tot Nationale ombudsman. Hij is in 1987 gepromo-veerd aan de Universiteit van Tilburg op een onderzoek naar de betekenisvan onafhankelijke rechtspraak in de democratische rechtsstaat. Tot zijnbenoeming als Nationale ombudsman was Alex Brenninkmeijer rechterbij verschillende rechterlijke colleges. Zo was hij van 1995 tot 2002vicepresident bij de Centrale Raad van Beroep (sociale zekerheid enambtenarenrecht). In 1992 werd hij hoogleraar burgerlijk procesrecht aande UvA, in 1995 hoogleraar staats- en bestuursrecht bij de UniversiteitLeiden en kleedde hij de Albeda-leerstoel voor arbeidsverhoudingen bijde overheid en ADR (Alternative Dispute Resolution). Daarnaast was hijredacteur van verschillende juridische bladen en is hij thans hoofd -redacteur van het Handboek Mediation en het Tijdschrift voor Conflict-hantering.

Leny de Groot-van LeeuwenProf. dr. L.E. de Groot-van Leeuwen is hoogleraar Rechtspleging, voor-zitter van het gelijknamige onderzoeksprogramma en bestuurslid van hetonderzoekscentrum Staat en Recht van de Faculteit der Rechts geleerd -heid van de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. Zij publiceerde in boekenen tijdschriften over de juridische beroepen en de legitimiteit van recht-spraak.

Jeffrey RachlinskiProf. dr. J.J. Rachlinski holds a B.A. and an M.A. in psychology from theJohns Hopkins University, a J.D. from Stanford Law School, and a Ph.D.in Psychology from Stanford. In 1994, Rachlinski joined the faculty atCornell Law School. He has also served as visiting professor at the University of Chicago, the University of Virginia, the University of Pennsylvania, Yale and Harvard. He is currently also Erasmus Professorof Empirical Legal Studies at the Erasmus University School of Law. Rachlinski’s research interests primarily involve the application of cognitive and social psychology to law with special attention to judicialdecision making.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Over de auteurs

7

Foto: R

ob van

Hilten

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 7

Eric RassinProf. mr. dr. E. (Eric) Rassin studeerde Nederlands recht en gezondheids-wetenschappen. Thans is hij aangesteld aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam als rechtspsycholoog. Daarnaast verzorgt hij op freelancebasis pro justitia rapportages.

Prof. mr. J.D.A. (Hans) den Tonkelaar en dr. S. (Suzan) Verberk zijn deredacteuren van Rechtstreeks.

rechtstreeks 2/2012

8

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 8

JustitiaAlex Brenninkmeijer

9

colu

mn

‘De president van de rechtbank resideert inhet Paleis van Justitie en waakt over debelangen van Justitia.’ Deze beschrijvingvan het werk van de rechter klinkt in dezetijd als een anachronisme. Het kan verkeren.De wetgever heeft de president inmiddelsomgedoopt tot voorzitter van het gerechts-bestuur, dan wel tot ‘voorzieningenrechter’,een gerechtsgebouw is een – marktconform– kantoor in plaats van een paleis, zoals hetGerechtshof te Leeuwarden en het beeld-merk van Justitia werd in de jaren negentigopgeëist door het toenmalige ministerievan Justitie. Destijds heb ik protest aan -getekend tegen deze beeldroof.

Justitia – grafisch verbeeld als een Justitiaop de vlucht – stond voor alles wat onderhet ministerie viel, van vervolging door hetOpenbaar Ministerie tot gevangeniswezen,van de toelating tot de uitzetting vanvreemdelingen en wat niet meer. Het kanverkeren. De keus van de wetgever om ‘depresident’ te verbannen uit het rechts bedrijfis niet geslaagd en uit de berichten in demedia blijkt de president nog dagelijksrecht te spreken. De bouwstijl van nieuwegerechtsgebouwen laat ik vanwege de her-ziening van de gerechtelijke kaart maar inhet midden.

Belangrijker is de vraag hoe het staat metJustitia. Het ministerie is inmiddels omgedoopt tot dat van Veiligheid en Justitie dat zich tooit met het ‘Rijkslogo’ dat voor ieder ministerie gelijk is. Het ministerie van Veiligheid en Justitie over-woog nog recent om via een ongekendeverhoging van het griffierecht 25 procent tekorten op de goede werken van Justitia.Het ministerie leek op deze wijze Justitiaachter financiële tralies te willen plaatsen.Dat is voor ons openbaar bestuur wellichtwel zo veilig, want Justitia zit met haar onafhankelijke rechtspraak dat bestuur kennelijk te vaak in de weg.

‘De Rechtspraak’ heeft bij de vernieuwingvan de rechterlijke organisatie in de jarennegentig gekozen voor een logo dat goedgenoeg is voor een doorsnee reclame -bureau. Dat is een gemiste kans en ik pleitervoor dat in deze onzekere tijden ‘derechtspraak’ het beeld van Justitia claimt alsbeeldmerk. Beelden zijn belangrijk. Als tv-camera’s de rechtspraak in beeld brengendan komt veelal een verbeelding van Justitia op het scherm. Justitia, al dan nietmet blinddoek, zwaard en weegschaal,wordt in brede lagen van de bevolking herkend als de herkenbare en unieke

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 9

verbeelding van de rechtsprekende functie.En niet alleen herkend, maar veelal alszodanig ook gewaardeerd. Justitia is nietalleen een sterk beeld in onze samenleving,maar ook een functie die als essentieelwordt aanvaard. Ondanks incidentele rechterlijke dwalingen en soms geslaagdewrakingspogingen is het vertrouwen in derechtspraak groot.

Is de naam van Justitia en haar verbeeldingzo belangrijk voor de rechtspraak? Ik meenvan wel. Rechtspraak is niet alleen een juridisch technische kwestie. Het gezag vande rechter is mede afhankelijk van beeld-vorming in de ‘mediacratie’ waarin wijleven. In deze tijd waarin door de politiekvaak druk wordt gezet op onafhankelijkerechtspraak, is het belangrijk dat de recht-spraak tegenspel biedt. Niet alleen tegen-spel met mooie missies, nota’s en adviezen,maar ook maatschappelijk, door de rol vanJustitia helder zichtbaar te maken. Rechter-lijke uitspraken kunnen maatschappelijkeimpact hebben, maar moeten dan dooreffectieve communicatie en met aanspre-kende beelden over het voetlicht gebrachtworden. Het beeld en het verhaal van Justitia gaan in het Westen terug tot eenculturele traditie van eeuwen, een traditiedie nog steeds mensen kan aanspreken.Mijn advies aan de Rechtspraak is om dieculturele traditie levend te houden. En zoekdaarbij ook aansprekende gezichten dievoor Justitia spreken. Persrechters kunneneen goede rol vervullen in concrete zaken.Maar als het om meer algemene kwestiesrond ‘de Rechtspraak’ gaat, is het

ongelukkig wanneer het verhaal van Justitianiet op gezaghebbende wijze door eenvaste vertegenwoordiger voor de cameragebracht wordt. Plaats daarbij overal waarde camera rechtspraak in beeld wil brengeneen verbeelding van Justitia en zet haar opiedere brief en ieder vonnis. Voeg daarbijhet adagio van de Engelse collega’s: ‘Justice must not only be done but it mustseen to be done’.

Het stokje van deze estafette geef ik dooraan Kees van den Bosch, hoogleraar socialepsychologie aan de Universiteit Utrecht.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Justitia

10

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 10

Inleiding op ‘Judicial psychology’ van J.J. Rachlinski

Eric Rassin

Het afgelopen decennium hebben psychologen zich in toegenomen mate gewaagd aan kritiek op het functioneren van Justitie. In Nederland waren rechterlijke dwalingen zoals diein de Schiedammer parkmoord aanleiding daartoe. Maar de toegenomen interesse in derechtspsychologie is niet beperkt tot Nederland. Inmiddels is er dan ook een aanzienlijkehoeveelheid internationale literatuur met relevantie voor de rechtspraktijk. Eén van deinzichten die deze literatuur biedt, is dat rechters, net als andere mensen, ten prooi vallenaan allerlei denkfouten, vooroordelen en gebrek aan kennis. Tegen deze achtergrond is hetfrappant dat artikel 338 Wetboek van Strafvordering het volgende dicteert: ‘Het bewijs datde verdachte het ten laste gelegde feit heeft begaan, kan door den rechter slechts wordenaangenomen, indien hij daarvan uit het onderzoek op de terechtzitting door den inhoud vanwettige bewijsmiddelen de overtuiging heeft bekomen’. Sommigen zien in deze bepalingeen extra waarborg. Immers, het bewijs moet niet alleen wettig zijn, maar ook nog eensovertuigend. Voor anderen is het fenomeen overtuiging echter problematischer. Hoe rakenrechters overtuigd? Zijn daar richtlijnen voor? Kan het proces van overtuigd raken wordengeverbaliseerd en gedoceerd aan studenten? Kan dat proces worden gecontroleerd? Het antwoord op dit soort vragen lijkt negatief. Volgens Cleiren zien sommige rechters de rechterlijke overtuiging in het licht van ‘intuïtie, Fingerspitzengefühl, ervaring en praktischewijsheid’ (Cleiren 2010, p. 259-267). Dat zijn termen die voor menig wetenschapper al teabstract zijn. Sterker nog, van ‘intuïtie’ moeten veel academisch psychologen niets hebben(Grove 2000, p. 19-30).

Waar de klinische intuïtie volgens academisch psychologen op termijn plaats zal moetenmaken voor protocollen, richt Rachlinski in het hoofdartikel zijn pijlen op de rechterlijkeintuïtie. Rachlinski betoogt niet dat de op intuïtie gebaseerde overtuiging moet verdwijnen,maar wel dat rechters haar stelselmatig dienen te controleren met expliciete rationele overwegingen. De rechterlijke intuïtie behoeft volgens Rachlinski controle omdat hij nietbeschermd is tegen ‘hidden influences on judicial decision making’. Om te beginnen definieert Rachlinski intuïtie als de snelle, geautomatiseerde kennis die we hebben: een eer-ste indruk, een niet-pluis-gevoel, een snelle conclusie ten aanzien van een simpel probleem.Deze intuïtieve kennis (systeem 1 genoemd) wordt afgezet tegen de welbewuste, over-

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Inleiding op ‘Judicial psychology’ van J.J. Rachlinski

11

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 11

dachte, liefst zuiver rationele kennis (systeem 2). Vervolgens fileert Rachlinski systeem 1door te bespreken in hoeverre het allerlei ongewenste invloeden impliceert, althans toelaat.Zo kunnen negatieve emoties zoals angst, boosheid en wraakgevoelens worden genoemd.Deze emoties staan in de weg aan de gedistantieerde, objectieve rol die de rechter heeft alshet gaat om beantwoording van de schuldvraag. Maar, zo betoogt Rachlinski, een volledigemotieloze rechter is evenmin wenselijk, alleen al omdat een dergelijke rechter zijn oordelenmet weinig overtuiging zal presenteren. Rachlinski laat vervolgens zien dat systeem 1 er insommige gevallen naast zit: het resulteert in ronduit foute conclusies. Interessant is dat wedesondanks behoorlijk zeker zijn van de juistheid van die (foute) conclusies. Een ander probleem is dat het intuïtieve denken gevoelig is voor wat heet ‘framing’. Hoe iets wordtgepresenteerd doet ertoe. Zo klinkt het voor veel mensen aantrekkelijker om mee te doenaan een loterij met een winkans van 30% dan aan een variant waarbij er 70% kans is dat menniets wint. Dit terwijl beide loterijen in werkelijkheid hetzelfde doen. Een iets serieuzervoorbeeld. Wie interesse heeft in de criminologische vraag naar de oorzaken van criminali-teit zal al snel in de literatuur terechtkomen over sociale processen (maatschappelijkeonvrede, verkeerde vrienden), disfunctionele leergeschiedenis, overvloed aan testosteron,(nor)adrenaline en wellicht psychopathie en antisociale persoonlijkheidsstoornis. Wie devraag spiegelt (waarom houden sommige mensen zich niet aan de regels?), komt echter inheel andere literatuur terecht, bijvoorbeeld die over serotonine, problemen met inhibitie endelay of gratification. De manier waarop een opdracht is geformuleerd, heeft kortom eensterke, soms onbedoelde invloed op de subsequent gekozen oplossingsstrategie. En het isinteressant om de vraag op te werpen of rechters ook ten prooi vallen aan dit fenomeen.Rachlinski betoogt in zijn artikel in ieder geval dat het ook voor rechters lastig is om aandergelijke framing-effecten te ontsnappen. Nauw samenhangend met het framingeffect is dat mensen nogal eens moeite hebben metstatistische wetmatigheden. Zo denken sommigen dat de kans om blind een rode knikker uiteen zak te trekken groter is als het gaat om een zak waarin 10 rode en 90 blauwe knikkerszitten, dan wanneer er 1 rode en 9 blauwe in zitten. Het verband tussen dit soort voorbeeldenen de moeilijkheden bij de interpretatie van NFI-rapportages is snel gelegd. Menig lezerweet hoe moeilijk het is om het verschil te onderkennen tussen de conclusie dat ‘de kansom dit DNA-profiel te vinden aannemend dat de verdachte de dader is, duizend keer zogroot is als de kans om het niet te vinden’ en die dat ‘de kans dat de verdachte inderdaad dedader is duizend keer zo groot is als dat hij dat niet is’.

Rachlinski gaat verder uitgebreid in op verankering. Oftewel: bij het nemen van beslissingenworden we, zonder het in de gaten te hebben, beïnvloed door informatie die in werkelijk-heid irrelevant is. Een laatste en niet te missen gevaar voor het intuïtieve denken is de confirmatiebias, ofwel tunnelvisie: de neiging om hypothesebevestigend te werken, met alsultieme uitkomst dat men een vals positieve conclusie trekt. Welbeschouwd behoeft het

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Inleiding op ‘Judicial psychology’ van J.J. Rachlinski

12

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 12

weinig betoog dat wanneer men alleen maar oog heeft voor bewijs voor een hypothese, terwijl tegenbewijs van tafel wordt geredeneerd, men een reële kans loopt om onterecht toteen bevestigend oordeel te komen.

Als jurist kan ik me voorstellen dat de lezer een drempel ervaart als het gaat om een Engels-talig stuk waarin centraal staat dat er van alles fout gaat tijdens het werk. Ondanks het feitdat het lezen ervan wellicht wat meer dan gemiddeld inspanning kost, is de inhoud van hetartikel de extra inspanning waard. Het artikel mag dan op Amerikaanse leest geschoeid zijn,dit maakt de relevantie voor de Nederlandse rechtspraak er niet minder om.Het kraken van enkele kritische noten kan in deze inleiding natuurlijk niet achterwege blijven. Om te beginnen moet het mij van het hart dat Rachlinski ten onrechte uitvoerigingaat op Wasons kaartselectie test als manifestatie van confirmatiebias. Die test is uiter-mate interessant, maar heeft geen betrekking op de confirmatiebias, maar op problemenmet logisch redeneren. In Wasons publicatie komt het woord confirmatiebias ook niet voor(Wason 1968, p. 273-281). Van groter gewicht is Rachlinski’s keuze om intuïtie gelijk te stellen aan systeem 1. Watintuïtie is, is uiteindelijk een definitiekwestie en het kan goed worden betoogd dat intuïtiemeer is dan ‘de eerste indruk’. Rachlinski gebruikt de Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) alsmaat voor intuïtie versus rationaliteit. Bij deze CRT is het echter per definitie zo dat hetintuïtieve antwoord onjuist is en het rationele correct. In werkelijkheid werkt onze ‘intuïtie’soms feilloos. Zo hebben we slechts een seconde nodig om iemands emoties af te lezen aanzijn/haar gelaatsuitdrukking. Daar komen geen rationele, weloverwogen gedachten aan tepas. Kortom, wie dweept met psychologische tests die intuïtie als fout definiëren en ratioals correct, kan niet anders dan concluderen dat intuïtie inferieur is aan ratio. Hiermee hangtsamen dat de vraag kan worden gesteld of problematische emoties, framing, gebrekkiginzicht in statistiek en confirmatiebias exclusief problematisch zijn voor systeem 1. Ik zoude stelling aandurven dat de beschreven invloeden onverminderd optreden bij het wel -bewuste systeem 2. In dat geval is het (hoewel nog steeds terecht) ietwat selectief om systeem 1 te bekritiseren vanwege de genoemde fenomenen. Immers, als beide systemen ingelijke mate gebukt gaan onder dezelfde fouten, is het oneerlijk om alleen systeem 1 daaropaan te vallen. Tot slot mocht men hopen dat er ietwat meer aandacht ware geweest voor deremedies voor de geschetste problemen. Voor zover mij bekend, zouden die gezocht moetenworden in protocollen ter vergroting van de transparantie van rechterlijke beslissingen.Immers, aangezien veel van de geschetste cognitieve tekortkomingen hardnekkig zijn enzich buiten onze bewuste beleving manifesteren, biedt samenwerking met kritische collega’sde beste kans om ze te compenseren (Tavris & Aronson 2011). Na deze kritische kanttekeningen nodig ik de lezer welgemeend uit om Rachlinski’s betoogte lezen en ter harte te nemen.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Inleiding op ‘Judicial psychology’ van J.J. Rachlinski

13

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 13

LiteratuurCleiren, C.P.M. (2010). ‘De rechterlijke overtuiging: Een sprong met hindernissen’. RM Themis, 5/6, 259-267.

Grove, W.M., Zald, D.H., Lebow, B.S., Snitz, B.E. & Nelson, C. (2000). ‘Clinical versus mechanical prediction: A meta-analysis’, Psychological Assessment, 12: 19-30.

Tavris, C. & Aronson, E. Er zijn fouten gemaakt (maar niet door mij): Waarom we dwaze overtuigingen, slechte beslissingen en kwetsend gedrag rechtvaardigen. Amsterdam: Nieuwezijds, 2011.

Wason, P.C. (1968). ‘Reasoning about a rule’. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (20): 273-281.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Inleiding op ‘Judicial psychology’ van J.J. Rachlinski

14

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 14

Judicial Psychology

Jeffrey J. Rachlinski

Judge Jerome Frank once remarked that ‘when all is said and done, we must face the factthat judges are human’ (Frank 1949, p. 410). Judge Frank also suggested that all judgesshould submit to psychoanalysis. Doubtless this suggestion was a product of its time, andneed not be taken literally today. But taken together these two statements support a need forjudges to engage in self-examination. In particular, Frank’s embrace of Freudian psycho -analysis as applied to judges reflects a need to understand the hidden motives of judicialdecision making. Although subjecting judges to Freudian psychoanalysis is apt to be an adhoc, imprecise way of understanding judicial motives, contemporary psychological researchhas shed light on some hidden influences on judicial decision making. This essay describessome of the findings of this research and offers suggestions as to its meaning for themodern judge.

Frank’s concern with judges’ hidden motives seems uncannily prescient. Contemporaryresearch on judgment and choice suggests that unconscious influences are an important partof human judgment. When making complex choices, people commonly rely on simple rulesof thumb, or mental shortcuts, that psychologists term ‘heuristics’ (Tversky & Kahneman1974, p. 1124-1131). People might deliberately rely on these processes, but by and large,they seem to operate without conscious awareness (Kahneman 2011). These heuristics canbe surprisingly accurate, but are a potential source of erroneous judgment. It would be surprising if judges were any different, and research suggests that they are not (Guthrie etal. 2001, p. 777-830). Accurate judging requires that judges become conscious of their decision making strategies and engage in careful, deliberative assessments of the casesbefore them (Guthrie et al. 2007, p. 1-44).

In this article, I review the tension between the heuristic sources of reasoning and deliber -ative reasoning as it applies to judging. I then discuss research suggesting that judges commonly rely on heuristic-based reasoning that can lead to poor judgment. I will also discuss settings in which judges seem to overcome or avoid reliance on common misleadingheuristics. I conclude by briefly identifying strategies judges might employ for reducingtheir reliance on misleading heuristics.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

15

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 15

1 Two Systems of ReasoningContemporary research in psychology has produced several lines of research that supportthe thesis that human beings use two different strategies for making decisions: intuitive strategies and deliberative strategies (Kahneman 2011). Psychologists sometimes refer tothese different strategies as different “systems”: System 1 (for the intuitive strategies) andSystem 2 (for the deliberative strategies). System 1 consists of judgments that are intuitive,associative, affective, heuristic-based, and rapid. System 2 consists of judgments that thatare deliberative, rule-based, calculating, precise, and slow. Although psychologists debatewhether the notion of two “systems” aptly characterizes the mind (Keren & Schul 2009,p. 533-550), few dispute the notion that some cognitive strategies are rapid and intuitivewhile others are slow and deliberative (Kahneman 2011). The concept of dual-process reasoning might be best thought of as a useful metaphor than a perfectly accurate model ofhuman judgment.

For judges, System 1 seems like a troublesome way of deciding cases. It is difficult to seehow justice can be served in the courts if judges rely on simple mental shortcuts that in alllikelihood lead to errors in judgment. System 1 is also the emotional system of reasoning.Most scholars and judges worry about the role of emotion in judgment (Maroney). Negativeemotions in particular, like anger and fear would seem to have no proper place in judicialdecision making. Even empathy can be problematic if it leads judges to favor some litigantsunfairly or create the perception that they do. Justice Sotomayor summed up the concernsabout emotion in judicial reasoning in her confirmation hearings by stating that: ‘Judgescan’t rely on what’s in their heart. It’s not the heart that compels conclusions in cases, it’sthe law’. Judges who lack or suppress system 1 would therefore seem to make the bestadministrators of justice.

The notion that judges should suppress intuitions, however, is likely to be impossible.Because the intuitive system of reasoning is rapid, intuitive judgments are inevitable (Kahneman 2011). The initial impressions created by intuitive judgments can then influenceor even guide subsequent deliberative reasoning. Because intuitive reasoning often operatesin an unconscious fashion, it can influence judgment without a judge’s awareness. Further-more, because intuitive reasoning produces highly confident judgments, judges might noteven feel the need to reason more carefully about the cases that they must decide. To besure, certain professions – notably engineers – seem to learn either to suppress their intuition or develop good intuitions, judging is not likely to be the same.

Neither is it desirable for judges to suppress their intuition. Judges sometimes need to makeconfident, assertive rulings. They need the parties before them to know that they can makean assertive decision to show the parties that they are in control of the proceedings. A timid

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

16

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 16

judge, it is said, is a lawless judge.1 Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio confirms this obser -vation with research on people with poorly developed intuitive and affective systems ofjudgment (Damasio 1994). These people are terrible decision makers. When faced with achoice, they can articulate detailed aspects of every option, but cannot seem to make achoice. Commonly their decisions produce regret and anxiety. Decision making seems torequire an intuitive component in order to create the confidence needed to make a finalcommitment to one choice or another. Judges would be ill served by trying to ignore theirintuitions.

A better model of judging would combine the best aspects of both the intuitive and deli -berative strategies. Judges would perhaps be well served by following the decision makingstrategy chess grandmasters use when playing tournaments. Chess grandmasters have set ofwell-developed intuitions about chess. When presented with a chess board, they willinstantly have an intuition about an appropriate next move – and in nearly all cases it will bea good move. Reliance on intuition would allow chess grandmasters to beat most players,but they would lose to other grandmasters if they relied solely on their intuition. In tourna-ments against other grandmasters, great chess players examine their intuitions about movescarefully, slowly, and deliberatively. In so doing, they are checking their intuition to see if itis misleading or has some flaw. Roughly half the time, they find a flaw in their intuition anduse a different move. The other half the time, they decide to follow their intuition. Judgeswould be well served by a similar strategy. Intuition is inevitable and remarkably accurate,but to ensure that they are making accurate decisions, judges must also check their intuitionwith careful, deliberative processes.

Do judges already know this? Some professionals, such as engineers or mathematicians,seem more naturally prone to rely on deliberative thinking than others. Legal reasoning hasstrong deductive, rule-oriented components. As such, the profession of judging mightattract people who are more prone to rely on deliberative reasoning. Alternatively, trainingand experience as a judge might teach judges to distrust intuition and rely on deliberation.

My collaborators, Chris Guthrie and Andrew Wistrich, and I have assessed this question(Guthrie et al. 2001, p. 777-830). Over the past 13 years, we have gathered data on the reasoning styles of several thousand trial judges in the United States, Canada, and morerecently also the Netherlands. We have described our methods in detail elsewhere (Guthrieet al. 2001, p. 777-830). Briefly put, we attend judicial education conferences at which weadminister brief questionnaires containing hypothetical scenarios that request legal judgments. In some cases we present judges with logical problems without any legal context.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

17

1 Wilkerson v. McCarthy, 336 U.S. 53, 65 (1948), Justice Frankfurter: ‘a timid judge . . , is intrinsically a lawless judge’.

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 17

We design questions (or borrow questions developed by others) that identify the reasoningprocesses that judges use.

One of the sets of questions we commonly administer to judges is a set of mathematicalproblems known as the ‘cognitive reflection test’ (CRT). The CRT is a simple, three-itemtest developed by Shane Frederick to assess people’s propensities to rely too heavily onintuition (Frederick 2005, p. 25-42). The CRT consists of three items:(1) A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How muchdoes the ball cost? _____ cents

(2) If it takes 5 machines 5 minutes to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machinesto make 100 widgets? _____ minutes

(3) In a lake, there is a patch of lily pads. Every day, the patch doubles in size. If it takes 48days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how long would it take for the patch to coverhalf of the lake? _____ days

Each of the three CRT items has a correct answer that is easy to understand, but each alsohas an intuitive, but incorrect, answer that almost immediately comes to mind to mostpeople (Frederick 2005, p. 25-42).2

The CRT items are simple in that ‘their solution is easily understood when explained, (. . .)[but] reaching the correct answer often requires the suppression of an erroneous answer thatsprings “impulsively” to mind’ (Frederick 2005, p. 27). Most people are unable or unwillingto suppress that impulsive response, however. In 35 separate studies involving 3,428 respondents, Frederick found that subjects, on average, got 1.24 of the three items correct,though responses varied across the subject pools (Frederick 2005, p. 27). For example, students at the University of Toledo obtained an average score of 0.57, while students at

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

18

2 Note that much of this paragraph and the next two are also reported in Guthrie et al. 2007, p. 1-44.

Most people think that 10 cents is the correct answer to the first problem. Though intuitive, this answer is wrong, asa bit of reflection shows. If the ball costs 10 cents, and the bat costs one dollar more, this means that the bat costs$1.10. Adding those two figures together, the total cost of the bat and ball would be $1.20, not $1.10, as specifiedby the problem. The correct answer is thus five cents. That is, the ball costs five cents, the bat costs $1.05, andtogether, they cost $1.10. Similarly, most people respond to the implicit numeric alliteration of the second questionwith the answer of 100. This answer is also wrong because if five machines make five widgets in five minutes, thismeans that each machine makes one widget in that five-minute time period. Thus, it would take only five minutesfor 100 machines to produce 100 widgets (just like 200 machines would make 200 widgets in that same five-minuteperiod). The third question combines the ‘one half’ with the 48 to make it seem like 24 is the right answer, but thisis also wrong. The correct answer, obvious upon reflection, is 47 days. If the patch of lily pads doubles each dayand fully covers the lake on the 48thday, it will cover half the lake the day before. Thus, the correct answer is 47days, not 24 days.

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 18

Massachusetts Institute of Technology obtained an average score of 2.18. Among all of thesubjects tested, only 17% got all three questions correct; nearly twice that many (33%) gotall three questions wrong.

The CRT illustrates the operation of two systems of reasoning in three respects. First,people perform poorly on the CRT, even though the questions are easy. The problems arenot like those on a test of intelligence, which tax the deliberative system’s abilities. Rather,they test the willingness to engage the deliberative system. Second, the intuitive answers arethe most common wrong answers provided. This shows that the source of the wrong answerslies with the reliance on the intuitive system. Third, people who select the intuitive answersbelieve that the problems are easier than those who answer correctly. In the bat-and-ballproblem, for instance, subjects who provided the intuitive response predicted that 92% ofpeople would solve the problem correctly. By contrast, subjects who responded correctlypredicted that only 62% of people would do so (Frederick 2005, p. 27). The intuitive systemproduces highly confident judgments, and hence those who rely on intuitive judgment aremore confident.

If judges are, by nature, deliberative individuals, they should perform much more like Massachusetts Institute of Technology undergraduates on the CRT than like ordinary adults.Our results, however, suggest that judges are not like engineers (Guthrie et al. 2007, p. 1-44).Table 1, below, presents the results of the CRT among judges and among several groups ofundergraduate students.

Table 1 Average Score on the Cognitive Reflection Test Among Judges and Others

Group Average CRT Score

MIT students 2.18Dutch Trial Judges 1.91Military Judges (US) 1.64Canadian Trial Judges 1.64Dutch Appellate Judges 1.59Carnegie Mellon students 1.51Harvard students 1.43Administrative Law Judges (US) 1.33Florida Trial Judges 1.23Web-based participants 1.10— State Appellate Judges 0.95Michigan State University 0.79

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

19

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 19

Judges vary widely in terms of their responses on the CRT. Dutch, Canadian, and U.S. Military judges score well on the CRT. Administrative judges and trial judges in Floridaalso score well relative to most adults, but also get most of the problems wrong. On thewhole, most groups of trial judges respond similarly to well-educated undergraduates atelite universities. That is, they rely on misleading intuitions, even when a moment’s reflec-tion would produce an accurate judgment.

In addition to the overall finding that judges are not like engineers, Table 1 reveals someinteresting differences among the judges. The U.S. Military judges score is perhaps notsurprising. More so than most judges, military judges are apt to have had backgrounds inscience, math, and engineering. Furthermore, the military judges preside exclusively overcriminal cases that arise from the code of military justice, which is highly detailed. OtherU.S. judges handle a wide variety of cases, including common law disputes and statutes thatare less detailed than the code of military justice. Similarly, although the Dutch judges arenot apt to be scientists either, they are civil law judges, not common law judges. Perhaps theexperience of applying the civil law, as opposed to the common law, tends to facilitate judges’ willingness to suppress their intuitive responses. Neither of these accounts explainsthe high scores of the Canadian judges, however.

The comparatively lower performance of the appellate judges is also interesting. Appellatejudges would seem to be more likely to use deliberative reasoning strategies than trial judges.The appellate process has several features that are conducive to deliberative reasoning: itinvariably includes a written back and forth among litigants, it does not usually requireimmediate decision and it usually involves deliberation with other judges. Each of theseshould facilitate a deliberative approach, so it is puzzling that the appellate judge shouldscore lower on the CRT. One possible explanation might be that the deliberative nature ofthe appellate process is precisely the problem. Appellate judges do not normally make snapjudgments of the sort we are asking for in these problems. They are also used to evaluatingmore detailed information, presented from two different perspectives. In effect, the CRTdoes not match their usual skill set. Appellate judges might be more deliberative, but theCRT does not give them the decision making cues that they are accustomed to relying upon.

Obviously, the CRT provides a limited window into judicial reasoning, at best. The resultssuggest that most judges are roughly as willing as well-educated adults to rely on misleadingintuition, but the problems are not set in legal contexts. In a series of studies, however, myco-authors and I have found that judges also commonly rely too heavily on intuitive reasoning while making judgments in legal settings. We provide several examples of suchsettings, below.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

20

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 20

2 Misleading Intuition in Legal SettingsIn a series of studies, we have found that judges sometimes rely on misleading intuitivedecision making strategies when evaluating legal cases. Specifically, we have found thatjudges rely on the framing of lawsuits, are distracted by the format of the legal question,rely on misleading numeric reference points, rely on information that is inadmissible, andsuffer from the confirmation bias.

A. Framing EffectsMost people categorize decisions involving financial outcomes into ones that involveimprovement from the status quo (gains) or deterioration from the status quo (losses) (Kahneman & Tversky 1984, p. 341-350). This categorization, or ‘framing’, of decisionoptions influences how evaluate their choices, and especially influences their willingness toincur risk. People tend to make risk-averse decisions when choosing between options thatappear to represent gains, and risk-seeking decisions when choosing between options thatappear to represent losses (Kahneman & Tversky 1984, p. 341-350). For example, mostpeople prefer a certain $100 gain to a 50% chance of winning $200 but prefer a 50%chance of losing $200 to a certain $100 loss (Tversky & Kahneman 1992, p. 297-323).

For those confronting gains, risk aversion is a reasonable perspective. Most economists contend that individuals with limited wealth should generally avoid risk and prefer certainty.The folk aphorism that ‘a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush’ is sound advice (although people might be excessively risk-averse, playing it safe even when gambling ismore sensible). The approach people take with respect to losses, however, is not consistentwith sound economic strategies. Risk-seeking decisions are costly. Research on framingsuggests that people become excessively attached to the possibility that they might not loseanything. Consequently, the gamble that includes an outcome that retains the status quobecomes intuitively appealing, even though selecting it is economically costly.

Framing effects influences people’s assessments of civil lawsuits because litigation producesa natural frame (Rachlinski 1996, p. 113-185). In most lawsuits, when plaintiffs evaluatesettlement offers, they choose between certain accepting an amount with certainty and gambling that further litigation will bring them greater returns. In effect, plaintiffs chooseamong gains. When defendants evaluate settlement offers, they choose between accepting aloss with certainty and gambling that further litigation will produce smaller losses. In effect,defendants choose among losses. Thus, if litigants frame lawsuits the way ordinary peopleframe decisions, plaintiffs will prefer settlement to litigation and defendants will prefer litigation to settlement. Obviously the amount in controversy and the likelihood of victorywill matter as well, but research on framing suggests that plaintiffs and defendants are aptto view the economics of lawsuits differently.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

21

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 21

To demonstrate this phenomenon, consider the following lawsuit, which we have given tolaw students, judges, and lawyers (all in the United States) (Guthrie et al. 2001, p. 777-830):

Imagine that you are presiding over a case in which a plaintiff has sued a defendantfor $200,000 in a copyright action. Both the plaintiff and the defendant are mid-sizedpublishing companies with annual revenues of about $2.5 million per year. They arerepresented by competent attorneys who have not tried cases before you in the past.You believe that the case is a simple one, but it presents some tough factual questions.There is no dispute as to the amount at stake, only as to whether the defendant’sactions infringed on the plaintiff ’s copyright. You believe that the plaintiff has a 50%chance of recovering the full $ 200,000 and a 50% chance of recovering $0. Youexpect that should the parties fail to settle, each will spend approximately $50,000 attrial in litigation expenses. Assume that there is no chance that the losing party at trialwill have to compensate the winner for these expenses.

The materials then state that, ‘[t]he case is approaching a trial date and you have scheduleda settlement conference’. Half of the judges reviewed the case from the plaintiff ’s perspec-tive, in which the choices involved potential gains. These judges read the following: ‘Youhave learned that the defendant intends to offer to pay the plaintiff $60,000 to settle thecase. Do you believe that the plaintiff should be willing to accept $60,000 to settle thecase?’ Thus, the judges learned that the plaintiff faced a choice between a certain $60,000gain or an expected trial verdict of $50,000; i.e., 50% x $200,000 judgment + 50% x $0judgment – $50,000 attorney fees = $50,000.

The other half of the judges reviewed the case from the defendant’s perspective, in whichthe choices involved potential losses. These judges read the following: ‘You have learnedthat the plaintiff intends to offer to accept $140,000 to settle the case. Do you believe that thedefendant should be willing to pay $140,000 to settle the case?’ Thus, the judges assignedto this condition learned that the defendant faced a choice between a certain $140,000 lossor an expected trial outcome of -$150,000; i.e., 50% x -$200,000 judgment + 50% x $0judgment – $50,000 attorney fees = -$150,000.

Both conditions thus presented the same essential option – avoid a risky outcome at trial byaccepting a settlement that was $10,000 above the expected value of a trial. In an intellectualproperty dispute of this sort, the parties are essentially splitting the $200,000. The circum-stance of being in the position of a plaintiff or a defendant should not change their perspec-tive, but it does for all three groups, as Table 2 shows, below:

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

22

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 22

Table 2 Settlement Rate by Condition and Subject Group

% Settling by Perspective

Plaintiff (Gain) Defendant (Loss)

Law Students 77% 31%Lawyers 44% 23%Judges 40% 25%

The framing of the settlement decision affected each of the three different groups who evaluated it. Although the litigants in this problem assessed settlement offers that were identical in terms of their expected economic value, the materials created the illusion thatthe plaintiff faced a choice between potential gains, and that the defendant faced a choicebetween potential losses. From the defendant’s perspective, the possibility of paying nothingto the plaintiff is hard to resist. The settlement seemed relatively more attractive to partici-pants evaluating from the plaintiff ’s perspective than from the defendant’s perspective. Consistent with the psychological literature on framing, the law students, lawyers, and judges were all more likely to favor a settlement for the plaintiff than for the defendant.

The low settlement rate overall is somewhat surprising because the settlement exceeded theexpected value of litigating in both versions of the problem. But the settlement offer alsoconceded most of the bargaining window to the adversary. Most of the lawyers and judgesthus likely perceived the offer as unfair or otherwise unreasonable, and rejected it. Most ofthe participants who evaluated the offer thus expressed a costly intuition against settlement.This was especially prominent among the parties evaluating the case from the defendant’sperspective. The prospect of accepting a loss seemed intuitively unappealing to the defen-dants.

The results suggest that judges are not likely to correct this error, either. Even though thedata on settlements show that defendants seem most resistant to settlement, and would thusbenefit most from judicial encouragement to settle (Guthrie et al. 2001, p. 777-830), thedata in our study suggest that judges who try to facilitate settlement are apt to lean moreheavily on plaintiffs.

B. Format EffectsContextual cues manipulate intuitive responses. Seemingly irrelevant aspects of a decision-making problem can direct a decision maker’s attention to different aspects of a multi-facetedproblem. In an example provided by psychologist Seymour Epstein, research participants

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

23

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 23

had an opportunity to win $20 if they could draw a red jellybean from an urn filled with redand white jellybeans while blindfolded (Kirkpatrick & Epstein 1992, p. 534-544). Epsteingave the participants a choice of drawing from an urn filled with 1 red and 9 white jelly -beans or an urn filled with 10 red and 90 white jellybeans. Even though the chances of success are identical, most participants chose to draw from the urn with the larger numberof balls. Many participants even preferred the larger urn when only it contained only sevenred jellybeans. The intuitive system induces people to see more chances to win in the largeurn, while blinding them to the fact that there are also more chances to lose. Just as in theCRT, people must recognize that their intuition is misleading and rely instead on some basicmathematics to see the urns as identical.

Epstein’s “jellybean phenomenon” translates directly into an important legal context – thatof involuntary civil commitment. In most jurisdictions, mentally disturbed individuals canbe confined against their will if a judge determines that they pose a danger to themselves orto others. The greater the likelihood of violence, the greater will be the justification for aninvoluntary commitment. This risk can be conveyed in different format which might triggerdifferent intuitive responses from judges. Informing a judge that 1 out of 10 individuals willcommit a violent act will have a different effect than telling a judge that 10 out of 100 individuals will commit a violent act. Researchers have demonstrated that this exact varia-tion influences clinicians’ judgments (Slovic 2000, p. 271-96). If this effect even influencesexperts, then it seems unlikely that judges will be able to resist it.

Judges are vulnerable to the kind of misleading intuitive phenomena that the format of aquestion creates (Monahan & Silver 2003, p. 1-6). Monahan and Silver provide an exampleof this in a study involving trial judges from across the United States attending a judicialeducation conference. These judges evaluated a hypothetical case of a mentally disturbedindividual to evaluate for civil commitment. The researchers asked the judges to identify thethreshold probability of violence that they felt would be necessary to justify a civil commit-ment. For half of the judges, they offered five choices: 1%, 8%, 26%, 56%, and 75%. Theother half chose between the following options: 1 in 100, 8 in 100, 26 in 100, 56 in 100, and75 in 100. The probabilities in all five offered choices were identical, but the variation produced different reactions. Judges who assessed percentages selected a modal thresholdof 26%, but judges who assessed frequencies selected a threshold of 8 in 100. The ‘8 in100’ choice implies that 8 people might be at risk from a decision not to inter the individualand makes it clear to judges that if made such decision on a regular basis, a fairly largenumber of people might become victims of violence. The percentage format does not seemto focus judges’ intuitions in the same way.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

24

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 24

Format can influence judges in other contexts. Andrew Wistrich, Chris Guthrie, and I askeda group of judges attending a national educational conference in the United States to sentence a hypothetical defendant who had been convicted of voluntary manslaughter. Thematerials described the crime (a stabbing in a bar fight) and the defendant’s criminal history(which was minimal). We asked the judges, ‘regardless of the sentencing system in yourhome jurisdiction, what sentence do you think is appropriate for this defendant’. The materials then provided a blank space for the judges in which to provide a sentence. For halfof the judges, this blank was followed by the word ‘years’ and for the other half, it was followed by the word ‘months’. In effect, we asked judges to sentence the defendant on oneof two different scales – months or years.

The scale affected the judges. The judges who sentenced in years imposed an average sentence of 9.6 years, while the judges who sentenced in months imposed an average sentence of 67 months – which corresponds to only 5.6 years. In the United States, somestates (and the federal criminal system) administer sentences in months, while others doleout punishment in years. Our national sample of judges, therefore, included judges who hadto identify a sentence using an unfamiliar scale. Judges who normally sentence in yearsmight have had have difficulty using months and vice versa. The deviations that such unfamiliarity might have produced, however, had a systematic effect. Judges used to sentencing in years were unwilling to inflict an appropriately large number of months.

C. AnchoringThe fact that judges have difficulty working in unfamiliar scales suggests that numericjudgments might be generally troublesome for judges. In particular, a phenomenon knownas anchoring might influence judge’s judgment.

Anchoring refers to the tendency to rely on numeric reference points to make numeric judgments (Tversky & Kahneman 1974, p. 1124-1131). Although this tendency might bereasonable in some settings, numeric reference points influence judgment, even when theyobviously convey no information and even when they are completely ludicrous (Ariel2010). In one demonstration of this, undergraduates were asked to identify the average priceof a textbook in the bookstore. Half of these subjects were first asked whether the averageprice was greater or less than $7,128.53 (reported in: Plous 1993, p. 146). Although all ofthe participants indicated that the average price was below that absurd estimate, those whowere first given this anchor provided higher estimates than those who were not. In anotherdemonstration, researchers had undergraduates guess the year in which Attila the Hun wasdefeated in Europe by writing down the last three digits of their phone number, adding 400to the result, placing the letters ‘A.D.’ after the result and then first guessing whether the

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

25

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 25

year was before or after the result (Russo & Schoemaker 1990). Even though this anchor istransparently unrelated to the event, subjects’ estimates of the year of Attila’s defeat correlated with their phone numbers.

Anchoring poses a potentially important source of erroneous judgment in the courtroom.When imposing criminal sentences and identifying civil damage awards, judges must makenumerical estimates reliably, even though doing so is difficult. A reasonable criminal sentence must incorporate a wide range of factors, including the defendant’s personal history, criminal record, and nature of the offense, into a single numeric assessment. Civildamages require translating a qualitative assessment of life and limb into a monetaryamount. Several mock jury studies show that a lawyer’s request for a particular damageaward can have profound effects on a jury’s awards, even when these requests are ludicrous(Chapman & Bornstein 1996, p. 519-540). These factors suggest that numeric requests fromlitigants, irrelevant information about a case, or even numeric amounts involving othercases might affect judges.

Several studies show notable effects of numeric anchors on judges. In one study (Guthrie etal. 2009, p. 1477-1530), we asked administrative law judges in the United States to identifyan appropriate damage award for a hypothetical civil rights violation filed with a cityhuman rights commission. We gave the judges a full page of details about the case andinformed them that under the relevant facts and law, they should make an award for themental anguish a plaintiff suffered after being fired for her ancestry (she was Mexican-American). All of the judges evaluated a piece of somewhat absurd testimony that the plain-tiff offered. Half were told that the plaintiff had stated that she recently saw a case similar tohers on a ‘court television show where the plaintiff received a compensatory damage awardfor mental anguish’. The other half saw the same testimony, except that the number‘$415,300’ was included before the word ‘compensatory’. Just as happened with under -graduates given an arbitrarily high anchor for the average price of textbooks, judges exposedto the high anchor in our study gave much higher estimates of damage awards. Judges exposed to the anchor gave a median award of $50,000 while those not exposed gave amedian award of only $6,250.

We have also found that anchoring affects sentencing decisions. In a study involving a groupof newly appointed trial judges, we asked the judges to sentence two different criminal defendants, who had been found guilty of unrelated crimes. One of the defendants wasfound guilty of assault with a deadly weapon – a crime that carried a maximum penalty of 3 years. The other defendant was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter – a crime that carried a maximum penalty of 15 years. Half of the judges first read about the defendantconvicted of assault, followed by the manslaughter, whereas the other half of the judges

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

26

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 26

read the cases in the opposite order. Although the crimes were unrelated, the order mattered.Judges who sentenced the manslaughter case first assigned this defendant an average of 8.6years, whereas judges who sentenced the manslaughter case after the assault case onlyassigned an average of 6.1 years. Contemplating the lesser sentenced made a lengthy sentence seem less appropriate to the judges. Judges who sentenced the assault case firstassigned an average of 1.2 years, whereas judges who sentenced the assault case after themanslaughter case assigned an average of 1.6 years. Contemplating the lengthy prison sentence for the manslaughter case made a short sentence for the assault case seem tooshort. The unrelated sentencing decision provided an anchor for the judges that influencedtheir assessment of the appropriate prison sentence. Sometimes the law itself provides an anchor. We found that reminding federal judges in theUnited States of the jurisdictional minimum amount for certain types of civil cases in thefederal courts ($75,000) reduced otherwise large damage awards (Guthrie et al. 2001, p. 777-830). This jurisdictional minimum was well known to the judges and reminding them of theamount conveyed no information to the judges about the case at hand. In a study involvingCanadian trial judges, reminding the judges of the maximum damage award for non-eco -nomic injuries doubled the average damage award in a personal injury case – from $40,000to $100,000. Similarly, in another study, disclosing settlement offers to judges influencedthe damage awards they assigned, even when the materials reminded judges that such offersare not admissible (Wistrich et al. 2005, p. 1253-1345).

Civil law judges are not immune from anchoring effects. In a study done in Germany,researcher asked judges to sentence a criminal defendant after first considering whether thesentence should be higher or lower than the sum of two dice rolled in front of the judges(Englich 2006, p. 188-200). Even though the dice provided a transparently uninformativereference point, it still influenced the judges’ sentencing decisions.Numeric reference points appear to change judges’ reactions to cases. In civil and criminalcases, high and low numeric reference points influence judges’ numeric judgments. Thesereference points act as anchors that influence how judges process cases, even when they arearbitrary, irrelevant, or even absurd.

D. Inadmissible Information Disregarding salient, relevant information is difficult (Wistrich et al. 2005, p. 1253-1345).The human brain incorporates and relies on important new information quickly and efficiently. This is part of the function that the intuitive reasoning processes perform. Whenever a judge encounters information that is inadmissible at a trial, or otherwise mustbe excluded from the record, they must ignore it and base their decision solely on the recordbefore the court. This might be difficult if the information to be ignored reveals someimportant weakness in the case or unsavory characteristic of the litigant.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

27

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 27

In our research, we have found that in general, judges find deliberately disregarding in -admissible evidence difficult, although they are able to manage it in some circumstances(Wistrich et al. 2005, p. 1253-1345). To assess judges’ ability to ignore inadmissible infor-mation, we conducted a series of studies in which trial judges in the United States eithermade a decision without being exposed to inadmissible information, or decisions in whichthey are exposed to such information, asked to rule that it is inadmissible, and then makethe same ruling. Judges who ignore the irrelevant information should reach the same decisions when they are exposed to the inadmissible evidence as judges who are neverexposed to the information.

We identified five circumstances in which judges were unable to ignore relevant, inadmis -sible evidence. First, as noted above, we found that settlement offers influenced judges’ ultimate damage awards, even though we reminded the judges that such offers are notadmissible evidence.

Second, we found that in a civil case, judges were unable to ignore information protected bythe attorney-client privilege. In our scenario, half of the judges learned that a plaintiff in acontract dispute admitted to his attorney that he was lying about a critical fact in the case.Although roughly half of the judges who never learned this information stated that theywould issue a judgment for the plaintiff, only one quarter of the judges stated that theywould be willing to do so when they learned that the plaintiff was lying about the merits ofthe case. Even though these judges asserted that they would not allow the protected infor-mation into the record, being exposed to the evidence nevertheless influenced their judgment.

Third, we found that judges were unable to ignore the past sexual history of a victim in asexual assault case. Half of the judges who had not heard about the victim’s history werewilling to convict the defendant, whereas only one in five were willing to do so when theylearned that the victim had a history of promiscuity – even though they had also ruled thatsuch evidence was not admissible. In this study, as in the study involving attorney-client privilege, nearly one-quarter of the judges admitted the testimony, even though doing sowas not consistent with the rules of evidence.

Fourth, we exposed half of a group of judges sentencing a criminal defendant for drug possession to information that suggested that the defendant was both trafficking and givingthe substance to a minor, who was supposedly his girlfriend. The information, however, wasobtained after a confidentiality agreement with the prosecution that prohibited the prosecutorfrom using it. The judges exposed to this information all agreed that it could not be usedagainst the defendant, but they also sentenced the defendant to a longer prison term.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

28

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 28

Finally, we found that judges reviewing a civil case assigned a lower damage award to plain-tiff who had an old criminal record than judges who were not exposed to this evidence, eventhough the record was largely irrelevant and the judges ruled it to be inadmissible.

These data suggest a serious problem for judges who act both as gatekeepers for evidenceand who must also decide the ultimate outcome of the cases. Such judges might have diffi-culty deciding cases solely on the record. The intuitive system will process negative infor-mation, regardless of whether it is meant to be admitted into evidence or not. This difficultydemonstrates an advantage for systems that rely on juries, as inadmissible evidence can bekept away from the jury. But the judge who both compiles the record and decides the casemust, of necessity, review the evidence to determine whether it is admissible.

Although there is no obvious inoculant to undo the effect of exposure to inadmissible testi-mony, our research identified two circumstances in which exposure to highly relevant, butinadmissible evidence did not influence judges. First, judges evaluating whether a criminaldefendant was guilty of a bank robbery were able to ignore an inadmissible confession. Thatis, those judges learned of the confession and ruled it inadmissible were as likely to convictthe defendant as those judges who had never been exposed to the confession. Second, judges asked to make a decision as to whether the police had probable cause for a searchwere not influenced by knowledge that the search had uncovered incriminating evidence.That is, the same percentage of judges concluded that probable cause was present in fore-sight (before the search had been conducted) and in hindsight (after the judge knew that thesearch had uncovered incriminating evidence). Given the pervasive influence of outcomeknowledge on judgment – which psychologists term the hindsight bias – this result is surprising. Subsequent research has replicated this result with a variety of scenarios withmany different kinds of judges (Rachlinski et al. 2011, p. 72-98).

Overall, the results suggest a somewhat mixed picture of how judges react to inadmissibleevidence. Several of the studies show that judges rule to suppress information and then relyon it. But two studies, both involving constitutional issues, show judges to have uncannyability to ignore highly relevant information. Taken together, the studies suggest that judgesare aware of the potential problem of exposure to inadmissible evidence. They try to inter-pret the rules of evidence in ways that will allow them to admit the inadmissible evidencewhen they are apt to rely on it, and can even ignore inadmissible evidence in certain settings.Nevertheless, judges do not entirely set aside evidence that is inadmissible and highly relevant.

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

29

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 29

E. Confirmation Bias3

The intuitive system can affect the kinds of evidence that people examine. For example,people suffer from a confirmation bias in assessing their beliefs (MacCoun 1998, p. 259-287). That is, people search actively for evidence that can support an existing belief andavoid efforts to uncover evidence that might disconfirm an existing belief. Scientists knowthat they must submit their hypotheses to tests that might disconfirm their theories, butlegal professionals lack this kind of training. Nevertheless, the confirmation bias can beespecially troublesome in legal settings.

The clearest demonstration of the confirmation bias is the Wason card-selection task, firstreported nearly fifty years ago (Wason 1966, p. 131-151). In this experiment, participantsface four cards, and are told that each of them has a letter on one side and a number on theother. The cards read as follows: ‘E’, ‘P’, ‘4’, and ‘7’. The participants are then asked to testthe hypothesis that ‘if there is a vowel on one side of the card, then there is an even numberon the other side’. They are then asked to turn over those cards – and only those cards – thatare required to test this hypothesis. Most participants correctly turn over the card showingthe letter ‘E’, but they also commonly select the card showing a ‘4’, or all of the cards. Thecard showing the ‘P’ is transparently irrelevant, as the hypothesis does not make any claimsregarding what might be on the other side of consonants. The card showing a ‘4’, however,is also irrelevant. Finding a vowel on the other side of this card would seem to support thehypothesis, but the consonant would not undermine the hypothesis, which makes no claimabout what lies on the other side of consonants. Because the ‘4’ card cannot either confirmor disconfirm the hypothesis, there is no need to turn it over. The card showing a ‘7’, how -ever, is important. If a vowel is on the other side of this card, then the hypothesis is false.Thus, the ‘E’ and the ‘7’ are the correct answer, although typically fewer than 10% of theparticipants choose only these two cards.

The results of the Wason task suggest that people look for evidence supporting their beliefs,but avoid evidence that might disconfirm them (MacCoun 1998, p. 259-287). People fail toappreciate the importance of investigating the possibility that their theories are wrong.Numerous studies of motivated reasoning and inference suggest that the confirmation biasis just as pronounced, or more, when the beliefs are important (MacCoun 1998, p. 259-287).People engage in a kind of wishful thinking that leads them to avoid evidence that willprove their beliefs to be mistaken.

Confirmation bias can create serious problems within the legal system. A fact finder suffering from the influence of the confirmation bias will allow an initial theory to influence

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

30

3 Much of this section is also reported in Rachlinski 2012.

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 30

how they gather and process subsequent information. An adversarial process might combatthe influence of the bias by allowing parties to expose the fact finder to disconfirming evidence. The confirmation bias likely poses the greatest risk to prosecutors and to judgesin inquisitorial systems because initial beliefs will guide further inquiry. A prosecutor orjudge might fail to consider looking for the kind of information that would undermine theirinitial belief that a particular suspect is guilty. Several studies in which subjects asked to actas prosecutors in reviewing a case file demonstrate that people avoid looking for discon -firming evidence and discount the importance of such evidence when they encounter it(Rassin et al. 2010, p. 231-246).

Trial judges also suffer from confirmation bias. In one study, we gave trial judges in theUnited States the original version of the Wason card-selection task, as described above.Only 9% got the problem right. As with other groups, most judges indicated that they wouldneed to turn over the even-numbered card to test the hypothesis that the cards containingvowels on one side have even numbers on the other. Other judges indicated that they wouldneed to overturn all four cards. As with our results on the CRT, these results suggest thatjudges do not suppress their intuition on abstract problems.

As with other reasoning problems we have investigated, we are more concerned with problemsthat have realistic content. For the confirmation bias, realistic content is particularly impor-tant, because in some settings, researchers have found that contextual cues can lead peopleto identify the correct solution (Cosmides & Tooby in: Barkow & Tooby (Eds.) 1992). Aswith the CRT, an abstract problem might not be a fair test for determining whether judgessuffer from the confirmation bias in a more realistic setting. Thus, we also tested an analogof the Wason card-selection task in a legal setting with trial judges. We asked the judges toimagine that they were presiding over a gender discrimination complaint. The plaintiff hadalleged that in the company she works for, ‘male supervisors only promote male employees’.This is intended as the analog to the statement that ‘if there is a vowel on one side of thecard, then there is an even number on the other side’. To create an analog to the cards, weinformed the judges that the plaintiff had partial information on four instances of promo-tions within the company: a male supervisor who promoted an employee of unknown gender; a female supervisor who promoted an employee of unknown gender, a maleemployee who was recently promoted; and a female employee who was recently promoted.The materials then informed the judge that the unidentified gender in each of these decisionscould only be obtained through further litigation. Although the materials indicated that thejudges could order that these identities be uncovered, doing so would be expensive, and sothey should only issue the order if the identities were relevant. The logical structure of theproblem is identical to the Wason card selection task, with ‘supervisors’ substituted for ‘letters’ (with ‘male’ as ‘vowel’ and ‘female’ as ‘consonant’), ‘employees’ substituted for

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

31

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 31

‘numbers’ (with ‘male’ as ‘even’ and female as ‘odd’). If context facilitated correct responses, this familiar context should have helped judge identify the correct response.

In our study, context was little help to the judges. Only 14% of judge in the United Statesidentified the correct answer. This represents at best a modest improvement over the 9%accuracy rate we observed with the original version. As with the original version of the problem, most of the judges recognized that they needed to investigate the decision made bya male supervisor; if he had promoted a female employee, the theory would be wrong, justas finding an odd number on the other side of the vowel would prove the theory wrong inthe original version of the problem. Judges also tended to seek the gender of the person whopromoted the male employee, just as they tended to think that the letter on the other side ofthe odd number was important. Several of the judges also incorrectly stated that all fourdecisions needed to be investigated, just as several in the original version indicated that allfour cards needed to be turned over.

Dutch judges performed much better on this task, as fully 32% chose correctly. (We did notgive the original Wason card-selection task to these judges.) To be sure, this means that themajority of judges still got the question wrong. The Wason card-selection task, however, ischallenging; one in three correct answers is an excellent showing. Furthermore, the superiorperformance of the Dutch judges relative to the U.S. judges is a notable result. The U.S. judges work within an adversarial system in which the parties choose what evidence to putbefore them. They rarely make choices about what evidence to pursue. By contrast, this taskis much more common for the Dutch judges. Although numerous other differences betweenthe groups might also account for the result, the superior performance of a group of judgesfor whom the bias is potentially more pernicious is encouraging.

Overall, these results suggest that the confirmation bias might be an important influence onjudges. To be sure, the study involved only a single setting – and not even the false con -viction setting. Judges might react differently to different problems. But the results are sufficient to warrant some concern that judges generally do not easily or naturally seekinformation that might disconfirm allegations.

3 ConclusionJudges have a strong intuitive side. In several contexts, judges seem to prefer intuitive judgments, even though intuition leads them astray. Judges also showed some resistance tomisleading intuitive judgments in some settings. The results suggest that judges can suppressmisleading intuition if they are given ways to do so. Some aspects of legal systems promotedeliberation, such as schedules, checklists and multi-factor tests. Sentencing guidelines areone example of the kinds of structured decision making that might induce a greater level of

rechtstreeks 2/2012 Judicial Psychology

32

rechtstreeks 2012-2 31-07-12 09:49 Pagina 32

deliberative reasoning. Being exposed to competing arguments also might trigger a judge tosecond guess her intuitive reaction to a case. Being forced to explain one’s decision, parti-cularly in writing, might also facilitate deliberative styles of reasoning that avoid misleadingintuitive judgment. Relatedly, group decision making might also slow judges down andinduce them to think deliberatively. Such mechanisms have their costs, of course. Writtenopinions take far longer to craft, adversarial systems tend to be more expensive than judge-directed systems, and sentencing guidelines tend to constrain judicial discretion too tightly.

Overall, this research does not suggest that intuition is to be avoided or wholly suppressed.Judicial intuition is apt to be accurate in many settings. The lesson of the research, however,is that judges need to question their own intuition, even when it seems to a judge that theirinitial reaction to a case is accurate. The error these studies suggest is not with judicialintuition itself, but with excessive confidence in judicial intuition. Judges must stop andthink to check their intuition against reality. Legal settings that facilitate this effort willlikely encourage sound legal judgments, while those that encourage judges to rely on theirintuition will be prone to error.

LiteratuurAriel, D. Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions, Revised & Expanded Edition, New York:Harper Perennial, 2010.