Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

Transcript of Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

1/17

196 CHAPTER slx Longuoge in sociol contextsand did not present evenrs in the correct order, as if they assumed that their listenersalready undeirtood what they were talking about. From these data, Piaget concludedth"t p..schoolers are egocentric and unable to take their listeners' perspectives, that"the effort to ,rnd.rst"nd other people and to communicate one's thought objectivelydoes not appear in children before the age of about 7 or7'/" (192611974' p. 139).ft $oUa be clear that both speech act theory and Piagett cognitive developmen-tal theory srress the relevance ofcontext for using and understanding language. For thespeech acr theorisrs, conrext meant the participants as well as the task or setting andp.io, .o.r',r.rsation. For Piaget, context meant the immediate physical context as wellas characteristics of the listener (what the listener knows, etc.). fu you will see, subse-quent researchers have investigated preschoolers in many contexts to see which contex-tual factors affect the children's language. That is, they assessed specific claims andaspects of these theories.

f,nNouncE tN soclAl coNTEXTSCommunicative competence entails the appropriate use of language in social contexts.It is precisely because communicative behaviors are so contextually sensitive that it isdi{ficult to describe clear developmental progressions for each of them (though seeNew Standards Speaking and Listening Committee, 2001, for general developmentalguidelines). Preschoolers usually perform differently in laboratory experiments than inlr.ryd*y interaction and converse differently with strangers than with those who are*orl fr*ilirr, making it hard to define and assess level of comPetence. This sectiontherefore focuses on several domains which provide relatively clear information aboutdevelopment in the preschool years: nonegocentric language, requests, conversationalskills, and language varieties.

Nonegocentric LonguogeIn some of the earliest efforts to assess young childrent communicative competence, re-searchers asked whether preschoolers communicate egocentrically. Using research pro-cedures modeled after Piaget's, these researchers demonstrated that young childrenhave the capaciry to take the perspective of the listener in certain circumstances. Thesestudies investigated referential communication, the ability to describe an item from aset of similar iiems so that a listener can identify it. An everyday example of referentialcommunication is a child describing a specific snack she wants her mother to find in apantry full of food.^ o'Neill (1996) hadZ-year-olds ask a parenr for help retrieving a toy. childrenwere more likely to name rhe toy or its location or to point to it when parents did notknow its location than when they did. In other words, the children took the parenrc'knowledge inro account when communicating. In contrast, preschoolers made un-cle"r refe*rences (e .g., "this one") and used gestures in trying to communicate with a

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

2/17

Longuoge in Sociol Conlexis"talking" computer (Montanari, Yildirim, Andersen, & Narayanan,2004). As thesestudies suggest, preschoolers generally perform better in common situations than inexperimental situations (Ninio & Snow, 1999) and with familiar items (e.g., sets ofanimals) than with unusual items (e.g., abstract shapes) (Yule, 1997). Providing aneyewitness account of an accident or crime might, therefore, prove to be especiallychallenging for preschoolers.

Taking a difitrent approach to the question of egocentrism, Shatz and Gelman(1973) investigated whether 4-year-olds would speak differently depending on whotheir listeners were. The preschoolers were asked to tell both an adult and a 2-year-oldabout a toy. Speech to the 2-year-olds tended to be shorter and simpler than that toadults, and it contained more phrases to get and hold attention (e.g., hey, looh).Inter-estingly, these same 4-year-olds tended to perform poorly on a referential communica-tion task and a physical perspective-taking task.

So are preschoolers egocentric in their attempts to communicate? The answer de-pends on context, in these cases the rype of task. 7hen preschoolers are familiar witha fairly simple task and are motivated to do it, their language does not appear to becompletely egocentric. Although it may seem that this conclusion is inconsistent withPiagett theory it is not. Piaget observed that preschoolers sometimes use egocentriclanguage and sometimes use more social language. They are not inherently egocentric.Rather, they may behaue egocentrically in certain situations and are more likely to be-have egocentrically than older children and adults, especially when the cognitive, lin-guistic, and social demands on them are great.RequesfsRequests are interesting parts of communicative competence for at least two reasons.First, requests exemplify the distinctions Austin made among the three components ofspeech acts: locutionary illocutionary and perlocudonary acts. Listeners must under-stand that very indirect, vague locutionary acts (e.g., "I'm bored," "Do you rememberthat book I lent you?") and very direct, explicit locutionary acts (e.g., "Entertain me,""Give me that book') may have the same illocutionary Purpose and perlocutionary ef-fect. Adults are rhought to infer the meaning of indirect requests by considering boththeir form and the conrext of their use . Researchers are interested in whether youngchildren have this understanding and therefore investigate children's comprehension ofindirect requests.

Second, effective speakers take context into account by varying the requests theyuse in different situations. Speakers have many forms of requests at their disposal, notonly in terms of their direct and indirect structure, but in terms of whether they con-tain semantic aggrayators (words or phrases that intensify the request; e.g., "or else,""right now") or semantic mitigators (words or phrases that soften the request; e.g.,"please" or giving reasons). Researchers are thus interested in how children produce re-quests and whether they re cognize the relationship beween the forms and functions ofrequests (see Becker, 1982,1984).

197

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

3/17

198 CHAPTER slx Languoge in sociol ContextsPreschoolers' Comprehension of Indirect RequestsBoth observational and experimental studies indicate that pteschoolers respond to indi-rect requesrs as requests for action. Two-year-olds respond as appropriately to requeststheir mothers phrase as questions as to those phrased directly (Shatz, 1978), and 3- and4-year-olds respond with appropriate actions when, for instance, telephone callers ash "Isyour Daddy there?" and when someone hints, "It's noisy in here" (Ervin-Tripp, 1977).Other evidence rhar preschoolers understand indirect requests to be requests foraction is found in the way children normally refuse such requests. Garvey (1975) o6'served 36 preschool dyads. lVhen children did not want to comply with indirect re-quests, they often justified and explained in terms of their inabiliry to perform therequested act (e.g., "I cant"), lack ofwillingness (e.g., "I dont want to"), lack of obliga-tion to comply (e.g., "I dont have to"), or their inappropriateness as the person beingasked to comply (e.g., "No, you'). Their comments reveal not only that theyviewed in-direct requests as requests, but that they understood the conditions under which theycould legitimately make requests and the conditions under which they should respond.

Experiments also show that preschoolers understand the intent of indirect re-quests. Leonard and his colleagues (Leonard, 'S7.ilcox, Fulmer, 6r Davis, 1978) assessedchildrent comprehension of embedded imperatives such as "Can you X?" and "tVillyou X?" Children watched videotapes of everyday interactions in which an adult usedan embedded imperative to make a request of another adult. Children judged whetherthe listener's subsequent behavior was in compliance with the request. Even 4- and 5-year-olds performed at beter than chance on these requests, even when the requestswere that the listener stop or change a behavior. Ervin-Tlipp, Strage, Lampert, and Bell(1987) obtained similar results.It may be that indirect requests like hints are not very difficult for young childrento understand. Because some indirect requests are so common in everyday speech, theymay nor require logical reasoning or the conscious consideration of form and context(Gordon & Ervin-Tlipp, l9B4). Preschoolers may routinely hear requests such as"Lunch time" (meaning "Clean up and wash your hands"), so that their intent has be-come obvious and the response automatic.Preschoolers' Production of RequestsMany contextual factors affbct the forms of requests adults use in different situations.They include the roles of the rwo people conversing, whether the seming is personal ortransactional, whether the requested action can normally be expected of the listener,and the relative starus or power of the two people. Most of the research on children hasfocused on status.In general, like adults, children tend to address direct requests with semantic ag-gravators to listeners oflower status and indirect requests with semantic mitigators to lis-teners of higher status. For example, preschoolers are more likely to use an imperative(e.g., "Gimme an K') with a peer and a more indirect request (e.g., "May I have an X?""Do you have an X?") with an adult (Ervin-Tiipp ,1977; Gordon & Ervin-tipp,l9B4;Shatz & Gelman, 1973). During role play, they have dominant puppets enact more

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

4/17

Longuoge in Sociol Contextt 199direct requests than submissive puPPets do (Andersen, 2000). They even make moresubtle differentiations, using requests that are more indirect with more dominant, big-ger peers than with less powerful peers (fflood & Gardner, 1980).

Preschoolers are, at least ro some degree, aware of the association between requestforms and the relative status of speakers and listeners and can recognize the social mes-sages thar requesrs convey. Preschool-age children reported that direct requests with se-mantic aggravators were "bossier" than less direct requests with semantic mitigators,which were seen as "nicer" (Becker, 1986). \7hen asked to make bossy and nice requests,these children produced bossy requests that were more direct and aggravated than theirnice requests. In other words, a peer who fequests the way a higher-status Person re-quests is bossy, whereas one who requests the way a lower-status person requests is nice.Requests themselves are not inherently bossy or nice. Rather, it is the use of the formsin particular contexts by particular people that imbues them with social nuances.In summ"ry pr.r.hoolers are quite adept at comprehending and producing dif-ferent request forms. They respond appropriately to indirect requests and understandconditions of their use . They also vary the forms of their requests systematically whenspeaking with individuals who are more or less powerful than they are.Conversotionol SkillsThe abilities ro take orhers' perspectives while communicating and to use requests arecomponents of conversations, which are even more complex communicative behaviors.Conversations require children to take turns, stay on topic, and repair misunderstandings.Thking TirrnsEven young infants can alternate turns while communicating with adults. By preschool,they rarely overlap rurns. However, preschoolers lack the precise timing of turns thatolder children and adults exhibit. They tend to rely on obvious cues that a speaker isdone, rather than anticipating upcoming conversational boundaries, which often resultsin long pauses between turns (Garvey, 1984). Tirrn-taking is particularly difficult forchildren when there are more than two speakers (Ervin-Tiipp, 1979). Phrases such asthe sentence-initial "and" and fillers such as 'y knov/' help older children hold the floorand keep their turns more effectively (Garvey, 1984;Pan 6r Snow, 1999).Maintaining the TopicPreschoolers' conversations are increasingly collaborative. These children rely less andless on simple strategies like sound play, repetition, and recasts of their partners' utter-ances to keep the conversation going (Pan & Snow, 1999).They become better able toelaborate on topics and themes (Ninio & Snow, 1996). They can have discussionsabout their days activities, get into prolonged debates about the relative merits of dif-ferent television shows, and enjoy long bouts of pretend play.

Some types of conversations are particularly challenging for preschoolers, how-eyer. Conversations over the telephone pose problems even though preschoolers havemany experiences using telephones (\Tarren & Tate, 1992).

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

5/17

240 GHAPTER slx Longuoge in Sociol ContextsOne way ro maintain a face-to-face conversation is to use cohesive devices. Theseprovide ways to link talk to earlier parts of a conversation. Comprehension depends onmaking the link. For example, 4'year'old Ben asks, "W'heret Spiderman?" and hisbrother Sam replies, "He's here." The pronoun "he" helps connect parts of the conver-sation without the need to repeat a prior phrase ("spiderman is here"). Another such de-vice is ellipsis, in which a speaker omits part of what was said before. For example, Benv/onders, "Did that dinosaur fall into the volcano?"'When Sam says, "No, it didn't," themissing information ("fall into the volcano") can be found by referring to a more com-plete form earlier in the conversation. These cohesive devices as well as others such as' connectives (e.g., because, so, then) become more frequent and diverse over the preschoolyears (Garvey, l9B4) and beyond (see discussion of anaphora in Chapter 5).Giving and Responding to FeedbackIn order for a conversarion to progress smoothly, listeners must provide feedback signal-ing confusion, and speakers must respond appropriately to that feedback. Very youngchildren can repeat or verifr their utterances when asked to do so. Preschoolers can is-sue and respond to queries requesting more specific responses, as in the following exam-ple of an interaction between two 3%-year-olds, drawn from Garvey (1984, p. 46):Girl: "But... uh... driverman. Ihavetodrivethis car."&ry, "'W.hat car? This car?" (touches a wooden car)Girl: "Yes."However, preschoolers are inconsistent and often inept at asking for clarification whenothers' communication is unclear and at repairing their own speech, especially whentheir listener's feedback is not explicit or when the situation is unfamiliar or unnatural(Garvey, 1984;Lloyd,Mann, & Peers, 1998). Elementary-age children are better ableto achieve mutual understanding in conversations.It is not until later that children are able to insert "uh-huhs," "rights," "I sees,"and head nods at appropriate moments to indicate continuing attention and satisfac-rory comprehension (Garvey, 1984; Lloyd, 1992).This rype of response is referred toas backchannel feedback.

Over the course of the preschool years, children become increasingly skilled attaking rurns, mainraining the topic of conversations, and dealing with misunderstand-ings and conversational breakdown. Although preschoolers are remarkably good con-versadonalists, older children require less conversational support from adults and arebetter able to conduct coherent, sustained conversations. Indeed, such communicativecomperence can continue to develop throughout the life span (see Chapter 10 as wellas Berman, 2004; Ninio 6r Snow 7999; and Pan & Snow, 1999)'Choices omong Longuoge VorietiesAnother aspect ofcommunicative competence involves the choices speakers make amonglanguage varieties. For example, one would speak differendy while giving a formalpresenrarion at school than when playing in onet neighborhood; when talking to chess

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

6/17

Languoge in Social Contexts 241buddies about strategy rhan when talking with younger siblings about television shows;when talking with one's elderly, Cuban grandparents than with younger, EuropeanAmerican neighbors. These language varieties include registers, dialects, and lan-guages. Registers (sometimes called speech codes or style) are usually thought of as formsof language that vary according to participants, settings, and topics. Dialects are usu-ally thought of as mutually intelligible forms of language associated with particular re-gions or defined groups of people. And languages are forms that are rypically notintelligible across groups. The distinctions among these three forms are not alwaysgreat; they are often based on social and political, rather than linguistic, considerations(Linguistic Sociery ofAmerica, 2A07).The Linguistic Sociery ofAmerica notes, for ex-ample, that different varieties of Chinese are considered dialects even though speakersof these different forms cannot understand each other, and that Swedish and Norwe-gian are separate languages but users ofeach understand the other.No one language variety is inherently more appropriate than another (though lis-teners have many stereorypes and prejudices concerning them). As with other aspects ofcommunicarive competence, whether a given variery is appropriate and effective dependson the conrext in which it is used. Two examples of language varieties are those associatedwith ethnicity and gender. Keep in mind that these varieties are only asociatedwirh eth'niciry and gender; there are tremendous differences across group members.Language and Ethnicity: African American EnglishAfricanAmerican English (AAE), avariery of English spoken by manyAfricanAmer-icans, is characterized in adult usage by its phonological, syntactic (seeTable 6.1), andpragmatic features. Phonological features thatbest distinguish it from most other varieties ofEnglish include simplification processes such asconsonant reversals and fi nal-consonant clusterreduction (Bailey &Thomas, 1998). For exam-ple, the word cold reduces to cole and askchanges o ahs. Syntactic features include mul-tiple negation, as in "He ain't got no car" andsubject-verb disagreement, as in "V{hat do thissay?" (Martin 8c'Wolfram, 1998). There arealso pragmatic features such as the use ofsignifring (also referred to as sounding caP?ing,and playing the dozens). Signifring is a type ofsarcastic or witty language play that allowsusers to inidate.a verbal "war" or make indirectcomments on socially significant topics. For ex-ample, one can describe someone by saying,"He is so cool that he even stops for greenlights" (Smitherman,2007). Rap and hip-hoplanguage are related speech events. Another

Mony Africon Americons speok o voriety ofEnglish characlerized by its phonologicol,syntoctic, ond progmotic feotures.

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

7/17

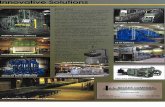

207 CHAPTER slx Longuage in Social ContextsSomple Differences between Stondord English (SE) ond Africon AmericonEnslish (AAE)

SE AAEPhonologtConsonant deletions

Final-consonant cluster reductionUnstressed-syllable deletionFinal-consonant deletionConsonant substitutionsFinal stop devoicingl{l and /v/ for medial and final /th//d/ for initial /th/

Consonant reversalsFinal /s/ + stop

SyntaxMuldple negationNon-inverted questionDeletion of auxiliarySub j ect-verb disagreementInvariant "be"Regularized possessive

goYernmenthivebadmouththese

ask

doesnt have'$7.ho is that?How do you do this?this saysShe usually drivesHe walks by himself

gov'menthibatmoufdese

aks

aint got no\flho that is?Ho',';;,6u do this?this sayShe be drivingHe walks byhisself

Source: Compiled from Bailey &Thomas (199S) and Martin & \Tolfram (1998).

pragmaric characteristic of AAE is the use of topic-associating (rather than topic-focused) narratives, which you will read more about in Chapter 10.

Like any other form ofEnglish, children's production ofAAE differs from that ofadults. Unfortunately, little research has been devoted to developmental change in theuse of this form (\Vyatt,1995). Preschoolers have been observed in pragmatic Perfor-mances such as signifring ('Wyatt, 1995). Many other characteristics that distinguishAA-E from Standard English (SE) do not emerge until after the preschool years (Battle,1 996; Terrell & Jackson, 2002) . Some of the earliest characteristics to appear are thoseinvolving the verb phrase, deletion of the auxiliary and negation (Battle, 1996;'Washington 6c Craig, 1994).In contrast, forms involving the habitual, invariant beand virtually all of the phonological features emerge rnuch later (Battle, 1996; Terrell&Jackson,2002).

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

8/17

Longuoge in Socio/ ConlextsIn addition to age, factors such as socioeconomic status and conrexr affect howoften children use AAL and which features they produce. It is more commonly usedamong working-class and low-income than middle-income African Americans andby boys more rhan girls (Craig & washington,20a4). One 5-year-old African Amer-ican girl ('Wyatt & Seymour, 1 990) used AAE features 10 percent of the time whiledescribing pictures and photos, but 43 percent of the time when discussing the char-acteristics, feelings, actions, and comments of other children. She omitted these fea-tures completely when addressing her Caucasian classroom teacher and used themapproximately 40 percent of the time when speaking to A.frican American peers. Someelementary-age African American children use AAE at home and other informal set-

tings and switch to SE in more formal, academic sertings, a tendency that is morepronounced in adolescence as children become more aware of the social significanceof SE (Battle, 1996).\,Vhy would speakers vary their speech so much across serrings, and why wouldthere be so much variation in the extent ofAAE use among speakers? Their behavior may

be due to perceptions of the efFectiveness or value of different varieties in those settings.In some settings, using a certain form enables speakers to establish and maintain socialbonds and to display cultural pride. In other settings, speakers may focus on the socialconsequences oflanguage variety for teachers' attitudes. They may also recognize that us-ing a certain variety has implications for educational and occupational access and success.Language and GenderSome research has suggested that there are feminine and masculine speech registers. Forexample, women are said to be more likely than men to use standard phonetic forms(e.g., pronouncing the final -inginwords), use polite forms such as rag questions or re-quests, react rather than initiate in conversations, and use parricular lexical items (e.g.,intensifiers, meaningless particles, politeness markers, rare color terms, expressive ad-jectives, and euphemisms). There is a great deal of controversy about whether, in fact,there are such gender dif[erences or whether these characteristics are more srereorypesor a function ofrole rather than ofgender per se.Overall, the language boys and girls produce is more similar than different. Themost consistent difference with respect to communicative competence is that younggirls tend to use more collaborative, supportiye, and mitigated speech sryles, whereasyoung boys tend to use more controlling and unmitigated speech sryles in interactionwith peers (Holmes-Lonergan, 2003; Leaper & Smith, 2004; Miller, Danaher, ErForbes, I 986; Sachs, i 987; Sheldon, 1 990) (though note rhe opposite finding for Chi-nese preschoolers by Kyratzis 6c Guo, 2001). For example, girls are more likely to asksomething like, "\7ill you be the doctor for a few minures?" and "She needs the littlepill, right?" In contrasr, boys are more likely to produce such sentences as, "Come on,be a doctor" and "Gimme your arm" (Sachs, l9B7). Similarly, preschool girls' storiesare more likely to describe stable, harmonious relationships (e.g., in families), whereasboys' stories are more likely to involve conflict, acrion, and disruption (Nicolopoulou,2002; Sheldon & Rohleder,1996).

203

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

9/17

244 GHAPTER slx Longuoge in Sociol ContextsSome stylistic differences in girls' and boys' conversations are nicely illustrated inDeHartt (1999) observations of same-sex, dyadic interactions. In the following exam-

ples, both sets of 4-year-olds are playing with a toy village.Jennifer: Could I have the table?Patricia: Okay. (gives Jennifer the table)Jennifer: Thanks. \X/hat if . . .Patricia: Oh, heret another biddy bed for me. (picks up a new piece)Jerunifer: Yeah, you got a biddy biddy bed.Patricia: Theret two biddy beds for me, for the daddy and the mommy.Jerunifer: No, that one is mine. I dropped it'Patricia: 'il/hoops. (drops a piece) Oh yeah. (gives piece back to Jennifer) Ittyours.Contrast that example with one involving two boys:Michael: (teasing) Ha ha ha ha. I gor the person. I got the person ha ha.Alan: I ha ha ha ha ha ha I got the person.Michael: (teasing) I got both of the brown dogs. I gor borh of the pups. I got

one of the pupPies'Alan: I got a brown dog. (pulls toys toward himself) Ah ha ha ha ha. I gotMichael: Hey, you have to spread 'em out (messes up Alant toys; Alan pullsthem back) and take 'em.Alan: Ah.Michael: Dont. (hits Alan on the head) Alan, ir's nor just yours. Dont be a

pig. Lett set'em up. (swings lake from play set at Michael) \(hoa,give me that. (holds hand out to block)No.lan:

There are many differences across children in the extent to which they use thesegender-related speech sryles. Moreover, their tendency to use these sgvles varies contex-tually. Preschool.., ,r. more likely to use them with peers of the same gender thanwith peers of the other gender (Killen & Naigles, 1995) and more with Peers than withsiblings (DeHart, 1996). Gender differences also become more pronounced with age,as you will learn in Chapter 10.Language of Different RolesAnother indication rhat children understand the connection between different lan-guage forms and context is the way they role-play. That is, by speaking differently*h..r.ttr.ting the roles, they reveal their knowledge of language registers. Andersen(2000) asked eighteen 4-,5-, and 6- to S-year-olds ro enact a family situation usingmorher, father, "rrd yo,r.rg child puppets; a classroom situation with a teacher andmo child puppets; and a doctor situation with a patient PuPPet and male and female

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

10/17

The Difficulty of Acquiring Communicotive Competence 205puPpets in medical attire. Children marked the different roles prosodically (mostlythrough pitch differences, bur also through inronation, volume, rate, and voice qual-iry),lexically (e.g., some use of technical medical terminology), and synracrically. Inthe family situation, for example, children used deep, loud voices as fathers, higherpitch for mothers, and even higher pitch and often nasalization or whining for chil-dren. \Vhen pretending to have the child address the father, they used more indirectrequests such as, "\7ould you button me?" rhan they did when pretending to addressthe mother. To her, they were more likely ro use direct requests such as, "GimmeDaddys flashlight" (Andersen, 2000, p. 236).,f/hen pretending to be fathers, chil-dren often used speech that was straightforward, unqualified, and forceful, and formothers they used speech that was more polite, qualified, and indirect (e.g., usingmany hints such as "Baby's sleepy''). Aronsson and Thorell (2002) observed similarbehaviors in preschool play.\fith age, children were able to use more linguistic devices to differentiate amongthe roles (Andersen, 2000). Initially, they relied on prosodic features and different speechacts, then added differentiated vocabulary and topics, and finally udlized syntax. Olderchildren were also better able to maintain these contrasts throughout their role play.As you have seen, preschoolers have many varieties of language at their disposal,including dialects and registers. M*y African American preschoolers are beginningto acquire the features ofAfrican American English and to use rhem differently in dif-ferent settings. Girls and boys are developing somewhat different styles, with girlscommunicating more collaboratively with peers than boys do. During play, youngchildren demonstrate basic knowledge of the registers associated with differenr roles.Preschoolers clearly have a command of some of the culrurally determined compo-nents of communication.

{ HE DTFFTCULTY OF ACAU|R|NGCOMMU N ICATIVE COMPETE NCEThe preceding discussion shows that children must adapt their language to difiGrentcontexts. They must learn, for example, that they may yell when they are playing out-doors but must use quieter voices inside and perhaps not even talk at all in settings suchas movie theaters and churches. Similarly, they must learn that they may discuss toilet-ing matters and details of recent illnesses with family members and physicians, bur notwith strangers, and that members of their soccer team may understand soccer jargonand expressions but that they must use other phrases with nonplayers. Not only mustchildren acquire a repertoire of communicative behaviors, they musr be able to recog-nize characteristics ofdifferent contexts and then use the behaviors that are expected,appropriate, and effbctive. This is clearly a difficult task for them.In contrast with the morphological and syntacric rules described in Chapter 5,there are usually not strict rules for communicative competence (Abbeduto & Short-Myerson, 2002; Becker, 1990). Rather, in specific contexrs, using or omitting a

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

11/17

206 GHAPTER slx Languoge in Socio/ Contextsparticular communicative behavior is seen as relatively appropriate or inappropriate''For.rrr.rpl., children do not always have to say Please in order to be polite and appro-p.i-,.. ii.t. "r. oth., ways to make polite requests' ,su"h a1 1ri18"M^y I have acookie?" The lack of hard-and-fast rules probably makes it difficult for children tolearn whether and when to exhibit different behaviors'

Another factor that makes acquisition of communicative comPetence difficult isthat many polite forms have no .le"r ref.rerrts. That is, it is not obvious what a form,rrh ^, pir)rrmeans. Furthermore, some forms, such as "thank you," that seem to have" -.*rrirrg (in this case, being thankful) _are often supposed to be used in situations*h.n th.t meaning i, .orrtr"'di.ted (such as when it is appropriate to thank elderlyAunt Gertrude fo. ihe hideous soclcs she sent for one's birthday) (Gleason, Perlmann'6r Greif, l9}4).Therefore the learning process is probably different from that de-scribed for other words in Chapter 4'Third, rhe conventions for comPetent communication in one setting (e.g',home) are often different from those in tther settings (e.g., school). To the extent thatthese conventions are diffbrenr, children may have trouble learning and adjusting to in-stitutional sertings and may also be judged negatively. The implications of this mis-match berween home and r.hool ,r. iramatically illustrated by children whose culturesare diffbrent from those of teachers and the classroom'

You will learn more about this later in the chapter'

{NrrurNcES oN THE ACaulslTloNOF COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCEAcquiring communicarive competence isdifficult, but children have some help' There"r. , ,r,rrib.r of ways families and schools contribute to the acquisition process' Fur-thermore, childrent knowledge and" their efforts to learn about communication also fa-cilitare their communicative development'

Fomily lnfluences on the Acquisitionof Communicotive ComPetenceIn general, it can be said that caregivers "so cialize" language. They use language to helptheir children become "o*p.,.ni-embers of their societies and cultures, comPetencereflected in part in the childrent language usage (schieffelin & ochs, 1996)'Virt,rily from birth, infants U.gi"io ,...ir. information about some of the com-municative behaviors that will help Ihem meet their social needs. You have probablyseen many parenrs waye the hands of their.little, preverbd infants and say things like"Say'hi' io M.r. Stanley'' or "Bye-bye, Grandpa"'

Much of the srructure of conversations may be learned in early interactions be-rween infants and caregivers, as indicated in chapter 2' Actions and talk (e'g" the use,:rf hrlto, plr^r,

^nd,thaih you) arehighlyorganized and predictable during social games

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

12/17

lnfluences on the Acquisition of Communicative Competence 207or routines such as Peekaboo and in give-and-take with objects. Such games providechildren clear and consistent information about a small number of sociJly signifi."rrtphrases. In these interactions, infants also learn about taking turns, rhe ,.rpo.rribili,i.,of both participants to keep the interaction going, how to focus on a theme or topic,and how to make the interaction cohere. Caregivers find ways to pull their infants intothe interaction, to help infants respond and participare, much as if they were having aconversation (Ninio 8a Snow, 1995).Once children exhibit some basic communicative competence, begin to partici-Pate more actively in interactions, and can anticipate sequences of behavior in the rou-tines, caregivers adapt their interactions (Becker, 1990). A number of interestingstudies have been conducted on how they do this during the preschool years.In a simple and clever study, Gleason and \7eint raub (1976) tape-recorded whathappened at two homes as trick-or-treaters arrived on Halloween .rrening. They alsofollowed two mothers and their children as they went trick-or-treating door to door.Many parents insisted that their children say "trick or trear" and "thank you," often us-ing the PromPt say.Their teaching is illustrated in the following example (Gleason &\Teintraub, 197 6, p. 134):

Girl's mother: (approaching a house) Dont forget to say "thankyou." (childrengo to door and return to sidewalk) Did you say "thank you,,,Sue, did you say "thank you"?Sue: Ya.

Girl's mother: Good.Boy's mother: Ri.lry, did you say "thank you"?Girl's mother: Did you say "trick or trear," Sue?Boy's mother: (approaching anorher house) 'lfill you remember to say "trickor treat" and "thank you"?Girl's mother: (children have walked to door; she calls ro rhem from the side-walk) Dont forget to say "thank you"

Gleason and other colleagues (Gleason er al., L9B4; Snow, perlmann, Gleason, &Hooshyar, 1990) as well as other researchers (Herot, 2002) havemade similar observa-tions. As seen on page 208, even carroonists acknowledge parental promptsorder to replicate and extend these findings I conducted a one-year longitu-dinal study of five families (Becker, 1994). Parents audiotaped everyday interactionsberween themselves and their preschoolers in their homes, particularly at the dinnertable, an important conrexr for language socialization (Blum-Kulka, 1997;Ely, Glea-son, MacGibbon, & zaretsl

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

13/17

2AB CHAPTER slx Languoge in Sociol Contexts

&t

Dolly's mother hos obviously prompted herobout oppropriote birthdoy porly expressions'

(@ Bi Keone, lnc. King Fealures Syndicote')

modeled, reinforced, occasionally posed hypothetical situations, evaluated behaviorafter rhe facr, addressed childrens comments about communication, and evaluatedothers' communicative behavior (see Thble 6'2)'one of the provocarive aspects of these findings is that most of the parents' inputwas indirect. sp.afi.rlly, p"r..r*' indirect comments on errors and omissions composedan avefageof 61 p....rrt of ,h. totd input (49-91Percent across the families). Indirect-.r.., ,..ri, a ris\y way to teach .orrr*rrr,i.r,ive competence, because children might notunderstand wh*i th.y are supposed to do. The finding that so much parental input is in-direct is counterintuiti r., b.c",rs. parents believe that displaying competence is impor-tant and a reflection of their own socialization comPetence

(Becker & Hall, 1989; Bryant'1999).One would think that parents would be explicit in order to maximize the chancesof th.i, children performing.orr..tly. Although these are not experimental findings andtherefore causal conclusions-cannot be drawn, it is likely that indirectness challenges chil-dren more cognitively and provides more information about communicative conven-tions rhan does direct,.*plicit input (Becker, 1988). In fact, mothers of preschoolersbelieve that indirect ,.rponr., plale cognitive burdens on children by helping them 'tothink rather than just prrrot" and "figure it out on [their] owri' (Bryant, 1999, p. 134) .

Parents are nor the only famlly members who socialize communicative comPe-tence. Siblings in several cultures ha-ve been observed to prompt appropriate behavior(Demuth, 1i86; Gl.rron, Hay' & Cain, 1989)' For example' a 5-year-old American

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

14/17

lnfluences on the Acquisition of Communicotive Competence 209Colegories of Poreniol lnput Regording Preschoolers' Communicolive Competence

PromptsDirect comment on omissionExplicitly point out the omitted behavior or that the child must produce this behavior; e.g., "Say'excuse me'when you cough."Indirect comment on omissionAllude to the omission; e.g., "\7hatt the magic word?"Direct comment on rror

Explicidy point out the childk error or that the child must correct behavior; e.g., "Dont talk withyour mouth fuIl."Indirect comment on enolAllude to the error; e.g., "\Mhat did you say?"Anticipatory suggestion

Suggest a behavior prior to an omission or error; e.g., "Dont forget to say'night-night' to Daddy."ModelingMod.eling

Provide the appropriate behavior before the child has the opportuniry to produce it; e.g., "Excuseme" as the child coughs.Tlaching siblirug

Modeling for the preschooler by commenting on younger siblingt behavior; e.g., Mother: "'What doyou say?" Sibling: "Thank you." Mother: "You're welcome. Very good "Parents demonstrate

Parents demonstrate prompts and behaviors as instruction; e.g., Father: "Go get my milk." Mother:"\fell, what do you say?" Father: "Please."Reinforcemeat

Verbal reinforcement following preschoolers' appropriate usage; e.g., "I like the way you say X]."Otherforms of rnpatHyp o th e t ca I s itu at o n

Pose a hypothetical situadon for didactic purposes; e.g., "'W'hat would you say if that ape came up toyou and said'hi'?"futroactiue eualuationComment on childt appropriateness well after the fact; e.g., "She said her prayers fearlier at lunch]all by herself \7ord for word, too. I'm really happy about that."Address child's comment

Respond to childt question, statement, or prompt about communicative competence; e.g., Child:"Itt a bad word, 'ugly."' Mother: "It's not a bad word, you just use it wrong."Eualuate anotlter

Seek child's evaluation of another persont behavior; e.g., "Right, Jane?"Source: Becker (1994), pp. 136-137.

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

15/17

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

16/17

lnfluences on the Acquisition of Communicotive Compelence 211ropic and take turns in such complex, triadic conversations (Barton & Tomasello,1994;Hoff-Ginsberg & Krueger, 1991). Younger siblings also have the.opportunity toobserve conversations berween their mothers and older siblings and are thereby ex-posed to a variery of communicative styles.If siblings affbct the acquisition of communicative competence, one would expectfirst-born children to differ from later-born children in their communicative skills.Hoff-Ginsberg (1998) investigated this possibility with l'l- to 2%-year-olds. Although,as previous research has shown, the first-born children exhibited more advanced lexi-cal and grammatical development, the later-born children had more advanced conver-sational skills in interactions with their mothers.

Even if they do not have siblings, preschoolers may be part of conversationswith several children and adults at the dinner table, a party, or at preschool, for ex-ample. These multiparry conversations operate differently than dyadic conversationsdo (Blum-Kulka & Snow, 2002). Multiparry conversations allow children to hearmore talk, hear greater varieties of talk, and observe and assume different conversa-tional roles. Such conversations require children to deal with participants' varyingdegrees of background knowledge and to be assertive and clever in finding ways toparticipate.This section has focused primarily on literature describing middle-class U.S.families because that is the population on which most of the research has been done.However, societies and cultures yary greatly in the pragmatic behaviors that adults so-cialize and the ways that they do so. For example, Canadian Inuit parents do not be-lieve children can reason until they are 5 years old. These mothers do not rypicallyconverse with their infants or view their vocalizations as talk. They do not drill or re-hearse language forms (Genesee, Paradis, & Crago, 2004).Insofar as those childrenultimately acquire communicative competence, it is clear that they learn by monitor-ing the conversations of speakers around them. (See Aukrust, 2004; Blum-Kulka,1997; Blum-Kulka & Snow, 2002; Rabain-Jamin, 1998; and Schieffelin & Ochs,1986, for information about the socialization of communicative competence in othercultures.)

There are several limitations in this literature that should be noted. First, causalconclusions cannot be drawn because the research is descripdve and correlational. Nei-ther experimental studies nor interventions have been done on the influences of fami-lies on the acquisition of communicative competence. Second, there are manyvariations across families with similar configurations (Mannle & Tomasello,lgBT).Not all mothers behave the same way, nor do all fathers or all siblings. For example,Davidson and Snow (1996) failed to find that middle-class, highly educated fathers ofkindergartners used more challenging language than mothers. 'We must also exercisecaurion in generalizing results of studies of relatively few families. Third, context influ-ences parental behavior to a greater extent than parental gender does (Lewis, 1997).The setting, the task, and other situational characteristics strongly affect how familymembers interact with preschoolers.

-

8/12/2019 Becker Bryant (2009) 196-212

17/17

212 CHAPTER slx Longuage in Sociol ContextsSchools' ond Peers' lnfluence on the Acquisitionof Communicotive CompetenceTeachers who provide opportunities and encourage children to talk for a wide varieryof purposes, in different situations, and with different audiences also help childrenl."rn to communicate effectively (Chall & Curtis, l99l). More specifically, childrenneed a variety of experiences communicating in order to learn the functions of lan-guage, different forms of discourse, and the conventions for using language appropri-at.ly. Val"able experiences include informal conversations between children andteachers and among children (not to mention with the principal, other teachers, Par-ents, and members of the community), games, small-group projects, storytelling, roleplaying, and the integration of communication across the curriculum (Chall & Curtis,1991). Children should not just be talked to, they should be able to develop commu-nicative competence in relevant, interesting, everyday situations. Having access to avariery of materials, interacting in small areas or centers within the classroom, and hav-ing long periods for interaction also appear to promote communicative competence inthe preschool years (Cole, 1995).

Furthermore, teachers explicitly teach some rules governing communicative be-havior specific to the classroom (Fivush, 1983). Effective teachers announce both re-strictive rules (e.g,, no screaming) and prescriptive rules (e.g., Pay attention, followroudnes) from the beginning of the school year and attempt to correct children's vio-lations of these rules. In contrast, there are other rules that children must infer from theongoing interaction. Fivush observed that teachers do not explicitly teach childrenabout turn-taking or that only teachers can initiate topics.

School also affords children the opportunity to interact with peers. Peers proba-bly affect communicative competence in a variety of ways. They may be similar to sib-lings as relatively uncooperariye conversational partners and thus contribute to thepr.rr,rr. preschoolers feel to communicate more clearly and effectively (Mannle 6CTomasello, l9B7).Interactions with peers are frequent, sustained, and emotionally en-gaging, and so provide a developmental context that promotes narrative and other.ol-o.ri."ti"eikilk (Nicolopoulou 8c Richner,2004). Peers also participate in formsof communicarion that are different from those of adult-child speech (Blum-Kulka &Snow, 2004), but, like adults, may correct peers' communicative behavior (Nakamura,2001). Their special kinds of humor and disagreements, the topics about which theytalk, and their explicit socialization about language provide communicative experiencesthat no doubt complement those experienced with adults.

Teachers can foster communicative competence in preschoolers who have diffi-culties interactingwith peers (Brown & Conroy, 2OO2). Effective intervention includestraining peers to use srrategies that engage less skilled peers in interaction. Teachers canalso use sociodramatic play to teach and prompt new skills. Finally, teachers ca{1 re-inforce communicarive competence and help introduce children to the "potentialsocial rewards of peer interactions'"