Air Navigation Services - Universiteit Leiden

247

Transcript of Air Navigation Services - Universiteit Leiden

Air Navigation ServicesCross-border provision of air navigation

services with specific reference to Europe: Safeguarding

transparent lines of responsibility and liability

Cross-border provision of Air Navigation Services with specific reference to Europe: Safeguarding transparent lines of responsibility and liability PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof. mr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op donderdag 29 november 2007 klokke 11.15 uur door Niels van Antwerpen geboren te Nieuw-Vennep, in 1975

Promotiecommissie promotores: prof. dr. P.P.C. Haanappel

prof. mr. L.J. Brinkhorst

co-promotor: dr. P.M.J. Mendes de Leon referent: dr. F.P. Schubert (CEO Skyguide, Geneva) leden: prof. B. Havel (DePaul University, Chicago) prof. dr. S. Hobe (University of Cologne) prof. mr. J.H. Nieuwenhuis mr. R.D. van Dam (EUROCONTROL, Brussels) Een handelseditie zal verschijnen bij uitgeverij Kluwer Law International te Alphen a/d de Rijn onder ISBN 13 - 9789041126887

For I dipt into the future, far as human eye could see, Saw the Vision of the world, and all the wonder that would be; Saw the heavens fill with commerce, argosies of magic sails, Pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales; Heard the heavens fill with shouting, and there rain’d a ghastly dew From the nations’ airy navies grappling in the central blue; Far along the world-wide whisper of the south-wind rushing warm, With the standards of the peoples plunging thro’ the thunder-storm; Till the war-drum throbb’d no longer, and the battle-flags were furl’d In the Parliament of man, the Federation of the world. There the common sense of most shall hold a fretful realm in awe, And the kindly earth shall slumber, lapt in universal law. From Locksley Hall (1842) Alfred, Lord Tennyson

II__

Acknowledgements As Leonardo da Vinci said: ‘when once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return’. I was fortunate in tasting air- and space law and related policy through the post- graduate teaching program of the International Institute of Air and Space Law (Leiden University) by joining its first advanced masters of law program in air- and space law in the summer of 2000. The atmosphere of the institute, its network and, not less important, the classmates of the first year’s teaching program, have heavily contributed to the thoughts and enthusiasm that lies behind this study. Trying to mould ideas and building paradigm shifts is definitely a challenge and a constant struggle with oneself and, not less important, one’s laptop computer. The colleagues of KLM Royal Dutch Airlines have been of great support. I wish to express my indebtedness in particular to Jan-Ernst de Groot, Barbara van Koppen, Irene Schoute, Ben Berends and the entire team of the Corporate Legal Services. In relation to the subject to this study, I would like to thank Dr. Tissa Abeyratne, Jiefang Huang and Nicolas Banerjea-Brodeur for their spontaneous assistance to show me the way to various ICAO documents. Furthermore, in order to obtain the most topical information and further insides in the field of European air navigation services, Ann-Frédérique Pothier of EUROCONTROL has been of great support. Also, I thank Prof. Dr. Paul Dempsey of the Institute of Air- and Space Law (McGill University) for making himself available to exchange views and observations on the topic of this study and the beloved Maria D’Amico for her great help and organisational support within McGill University. Lastly, I would like to express my indebtedness to Peter van Fenema and George Tompkins Jr. who were always available to provide advice, joy and laughter. I must also mention the help of Paula van der Wulp and Judith Sandriman for managing the organisational challenges at the Leiden University and Anna Rich for her loyal support over the years and making herself available for making the final corrections. Also I would like to express my gratitude to Frank Manuhutu who was always there to exchange views, host dinner parties and drinks as well as Jeroen Vink for the cover design. I shall of course, never forget the love, support and patience of my parents, the pater familias Theo van Antwerpen and my friends during all these years that have made the research bearable. Niels Arnoud van Antwerpen Leiden, November 2007

Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................. II

TABLE OF CASES ..............................................................................................................................VI

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................................IX

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................11 1.1 TECHNOLOGY AND TRAGEDIES........................................................................................................11 1.2 THE MID-AIR COLLISION NEAR ÜBERLINGEN (LAKE CONSTANCE)...................................................15 1.3 OBJECTIVE AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS............................................................................................19 1.4 DIVISION OF CHAPTERS ....................................................................................................................22 CHAPTER 2 THE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK ..........................................25 2.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................25 2.2 PRINCIPLES OF INTERNATIONAL (AIR) LAW.....................................................................................25

3.4.3 Enforcement .........................................................................................................................64 3.5 PRELIMINARY REMARKS..................................................................................................................65

IV Table of contents PART 2 THE INTERRELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EUROCONTROL AND THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY

(INCLUDING EASA) ..................................................................................................................66 3.6 EUROPEAN COMMUNITY, EUROCONTROL AND EASA................................................................66

3.7 CONCLUDING REMARKS ...................................................................................................................80 CHAPTER 4 CROSS-BORDER PROVISION OF AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES.............85 4.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................85 4.2 CROSS-BORDER AND EXTRA-TERRITORIAL PROVISION OF AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES ..................86

4.6.1 Amending the Chicago Convention....................................................................................129 4.6.2 The Regional Air Navigation Plan (RANP) .......................................................................130 4.6.3 Positioning the RANP in international law.........................................................................134 4.6.4 The RANP as a multilateral vehicle ...................................................................................140

5.3.1 Luxembourg .......................................................................................................................156 5.3.2 Belgium ..............................................................................................................................156 5.3.3 The Netherlands..................................................................................................................157 5.3.4 Germany .............................................................................................................................160 5.3.5 Austria ................................................................................................................................162 5.3.6 Switzerland .........................................................................................................................163 5.3.7 Ireland.................................................................................................................................164 5.3.8 United Kingdom .................................................................................................................164

Table of contents V 5.4 THE ORGANISATION OF AIR NAVIGATION SERVICE PROVIDERS IN THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY..167

5.4.1 Air Carrier Transportation: Operating License and Route License ....................................167 5.4.2 Air Navigation Services: Certification and Designation.....................................................169 5.4.3 Service Provision Regulation – Entry into Force ...............................................................171 5.4.4 The Organisation of Air Navigation Service Providers ......................................................172 5.4.4.1 Principal Place of Operation and Registered Office (Ownership and Control) ................................ 172 5.4.4.2 Regulatory........................................................................................................................................ 173 5.4.4.3 Liability............................................................................................................................................ 174

5.5 LIABILITY FOR (CROSS-BORDER) AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES ......................................................174 5.5.1 Traditional Liability Concepts............................................................................................174 5.5.2 The Draft Convention on the Liability for Air Traffic Control ..........................................176 5.5.3 Inter-State Liability Concepts for Cross-Border Service Provision....................................178

5.6 TOWARDS A HARMONISED CROSS-BORDER LIABILITY REGIME FOR THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY ................................................................................................................181

5.6.1 Conceptual Liability Framework: Inter-State Liability and Third Parties on the Ground ..182 5.6.2 Contractual liability framework for the benefit of aircraft operators..................................188 5.6.2.1 The Airways Corporation of New Zealand ...................................................................................... 189 5.6.2.2 Draft contractual framework for GNSS (CNS/ATM) ...................................................................... 191 5.6.2.3 Airports and Airlines........................................................................................................................ 194 5.6.2.4 Preliminary Remarks........................................................................................................................ 195

5.7 CONCLUDING REMARKS ................................................................................................................197 CHAPTER 6 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .............................................201 6.1 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................................201 6.2 ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS FOR CROSS-BORDER PROVISION OF AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES ...................202 6.3 STRENGNTHENING THE RULEMAKING ROLE OF EUROCONTROL IN THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY ................................................................................................................205 6.4 THE ESTABLISHMENT OF TRANSPARENT LINES OF STATE RESPONSIBILITY BY ALLOCATING RESPONSIBILITY TO THE SUPERVISING AUTHORITY UNDER A MODEL DELEGATION AGREEMENT ....207 6.5 THE REGIONAL AIR NAVIGATION PLAN AS MULTILATERAL VEHICLE FOR CROSS-BORDER ARRANGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................209 6.6 ESTABLISH TRANSPARENT LINES OF (INTER-STATE) LIABILITY FOR THE PROVISION OF CROSS-BORDER AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES..................................................................................210 6.7 EXTRAPOLATING THE CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS BEYOND EUROPEAN AIRSPACE....212 APPENDIX I: MODEL AGREEMENT FOR CROSS-BORDER PROVISION OF AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES..........................................................................215 APPENDIX II: STRUCTURE OF PROPOSAL (GRAPHIC) .....................................................220

SAMENVATTING (SUMMARY IN DUTCH) ...............................................................................221

Table of Cases International Court of Justice Case Concerning the Aerial Incident of 3 July 1988 (Islamic Republic of Iran v. United States of America)…………………………………… 137 Case of the S.S. “Wimbledon” (United Kingdom, France, Italy, Japan v. Germany)……………………………………………………………………………….. 28 Chorzów Factory case (Germany v. Poland)……………………………………………… 100 Interpretation of the Statute of the Memel Territory (United Kingdom, France, Italy, Japan v. Lithuania)……………………………………… 94 Lighthouses in Crete and Samos (France v. Greece)……………………………………… 93 European Court of Justice Flaminio Costa v. Ente Nazionale Energia Elettrica (Costa v. Enel)…………………….. 57 N.V. Algemene Transport- en Expeditie Onderneming Van Gend & Loos v. Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen (Van Gend en Loos)……………………… 56 Germany Bashkirian Airlines v. Bundesrepublik Deutschland…………………………….... 15-19, 106 The Netherlands Vereniging Bewonersgroep Tegen Vliegtuigoverlast v. Dagelijks Bestuur van de Deelgemeente Hillegersberg-Schiebroek (Rotterdam Airport-case)……………………… 40 New Zealand Airways Corporation of New Zealand Ltd. v. Geyserland Airways Ltd. and White Island Airways Ltd……………………………………………………….…….. 189 United States of America Beattie et al v. United States of America (1984)…………………………………………... 92 Beattie et al v. United States of America (1988)…………………………………………... 92 Blumenthal v. United States of America (1960)………………………………………….... 89 D’Aleman v. Pan American World Airways (1958)……………………………………….. 89 Faat v. Honeywell Int’l (2005)…………………………………………………………….. 17 Richards v. United States of America (1962)……………………………………………… 89 Smith v. United States of America (1993)…………………………………………………. 93

VII

Table of International Conventions and Other Agreements The treaties referred to in this study are listed in alphabetical order in accordance with the abbreviations listed below, including the place and date when they were concluded. Accession Protocol Protocol on the Accession of the European Community to the

Eurocontrol International Convention relating to Co-operation for the safety of air navigation of 13 December 1960, as variously amended and as consolidated by the Protocol of 27 June 1997 (Brussels, 8 October 2002)

Amended Convention Protocol Amending the “EUROCONTROL” International

Convention Relating to Co-operation for the Safety of Air Navigation with Annexes 1, 2 and 3 (Amended Convention), 1430 UNTS 279

Antarctic Treaty Antarctic Treaty, 1 December 1959, 402 UNTS 71 ASECNA Convention Convention relative à la création de l’Agence pour la

Sécurité de la Navigation Aérienne en Afrique et à Madagascar [The Convention on the creation of the Agency for the Safety of Air Navigation in Africa and Madagascar], as amended in Dakar, 25 October 1974 (Unpublished)

Chicago Convention Convention on International Civil Aviation,

7 December 1994, 15 UNTS 295 Convention on the Law of United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the Sea 10 December 1982, 21 ILM 1261 COCESNA Convention Convenio Constitutivo de la Corporación Centroamericana

de Servicios de Navigación Aérea [The Agreement to Constitute the Central American Corporation for Air Navigation Services] (Tegucigalpa, 26 February 1960)

EC Treaty Consolidated Version of the Treaty Establishing the

European Community, 2002 OJ (C 325/3-159) EEC Treaty Treaty Establishing the European Economic Community, 25 March 1957, 298 UNTS 3 (also referred to as

Treaty of Rome) ESCS Treaty Treaty Establishing the European Coal and Steel

Community, 261 UNTS 140 EURATOM Treaty Treaty Establishing the European Atomic Energy

Community (EURATOM Treaty), 298 UNTS 167 EUROCONTROL Convention “EUROCONTROL” International Convention Relating to (1960) Co-operation for the Safety of Air Navigation,

523 UNTS 117

VIII Joint Financing Agreement Agreement on the Joint Financing of Certain Air Navigation (Greenland) Services in Greenland as amended by the Montreal Protocol of 1982 (ICAO Doc 9585) Joint Financing Agreement Agreement on the Joint Financing of Certain Air Navigation (Iceland) Services in Iceland as amended by the Montreal Protocol of

1982 (ICAO Doc 9586) Liability Convention Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by

Space Objects, 29 March 1092, 961 UNTS 187 Montevideo Convention Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States,

26 December 1933, 165 LNTS 19 Montreal Convention Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules for

International Carriage by Air, 28 May 1999 (ICAO Doc 9740)

Montreal Protocol The Protocol to Amend the Convention on Damage Caused

by Foreign Aircraft to Third Parties on the Surface, 23 September 1978 (ICAO Doc 9148)

Outer Space Treaty Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the

Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and other Celestial Bodies, 10 October 1967, 610 UNTS 206

Revised Convention Protocol consolidating the EUROCONTROL International

Convention Relating to Co-operation for the Safety of Air Navigation of 13 December 1960, as variously amended, Brussels, 27 June 1997 (EUROCONTROL, September 1997 Edition)

Rome Convention Convention on Damage Caused by Foreign Aircraft to Third

Parties on the Surface, 7 October 1952, 310 UNTS 181 Route Charges Agreement Multilateral Agreement Relating to Route Charges,

12 February 1981, 1430 UNTS 123 Vienna Convention on the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 23 May 1969, Law of Treaties 8 ILM 679 Warsaw Convention Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules Relating to

International Carriage by Air, 12 October 1929, 137 LNTS 11

IX

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms AASL Annals of Air and Space Law ADIZ Air Defence Identification Zone AEA Association of European Airlines Air Law Air and Space Law AJIL American Journal of International Law ANS Air Navigation Services ANSP Air Navigation Service Provider ATC Air Traffic Control ATFM Air Traffic Flow Management ATM Air Traffic Management ATS Air Traffic Services CADIZ Canadian Air Defence Identification Zone CANSO Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation CDM Collaborative Decision Making CEATS Central European Air Traffic Services Upper Area Control Centre CHICAGO Chicago Convention CFMU Central Flow Management Unit CNS Communication, Navigation and Surveillance DOHSA Death on the High Seas Act EANPG European Air Navigation Planning Group EASA European Aviation Safety Agency EC European Community ECAC European Civil Aviation Conference ECR European Court Reports EJIL European Journal of International Law ENPRM Eurocontrol Notice of Proposed Rule Making ERA European Regions Airline Association ESARR Eurocontrol Safety Regulatory Requirement ETS European Treaties Series EUROCONTROL European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation FAA Federal Aviation Administration FABs Functional Airspace Blocks FBA Functional Blocks of Airspace FIR Flight Information Region FTCA Federal Tort Claims Act FUA Flexible Use of Airspace GNSS Global Navigation Satellite System GPS Global Positioning System IATA International Air Transport Association ICAO International Civil Aviation Organization ILM International Legal Materials JALC Journal of Air Law and Commerce LJIL Leiden Journal of International Law LNTS League of Nations Treaty Series LoA Letters of Agreement Maastricht UACC EUROCONTROL Maastricht Upper Area Control Centre MET Meteorological Services NILR Netherlands International Law Review NUAC Nordic Upper Area Control centre

X OJ Official Journal of the European Union PICAO Provisional International Civil Aviation Organization PIRG Planning and Implementation Regional Group RAN Meeting Regional Air Navigation Meeting RANP Regional Air Navigation Plan RU Regulatory Unit of EUROCONTROL RVSM Reduced Vertical Separation Minima SES Single European Sky SESAR Single European Sky ATM Research programme SRC Safety Regulation Commission of EUROCONTROL TCAS Traffic alert and Collision Avoidance System UNTS United Nations Treaty Series ZLW Zeitschrift für Luft- und Weltraumrecht

11

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Technology and Tragedies In the old days pilots depended on daylight and clear visibility in order to operate a flight. They used landmarks such as rail-tracks, rivers and roads, to navigate the aircraft to their final destination. There was no supporting radio connection from the ground and controllers at airports, if at all available, limited their services to the waiving of flags or providing guidance through signage or lightning signals to provide pilots with particular landing- or take-off instructions. From the 1930s, airport control towers were gradually equipped with radio equipment that allowed direct contact with pilots. Radio aid was improved and subsequently also used for en-route air navigation services enabling pilots to plot their position by using radio beacons on the ground. The introduction of radar after the Second World War enabled ground personnel to identify and to plot the position, heading and air speed of aircraft. With the improvement of radio communication, this gradually resulted in a worldwide system of air navigation services. According to the annual report issued by EUROCONTROL’s performance review commission of 2006, which covers the airspace of the member states of EUROCONTROL, there were no less than 9,2 million controlled general air traffic flights in 2005. Traffic increased by 3.9 per cent compared to the previous year.1 A long-term prediction of the number of flights up to 2025 shows a trend of sustained traffic growth. Depending on scenarios with higher economic growth and lower fuel price, the number of flights range from 1.6 times to 2.1 times higher than the total number of flights in the year 2003, which were around 8, 3 million controlled flights.2 The growth of air traffic requires the generation of sufficient airspace capacity without jeopardising aviation safety. Various techniques and organisational developments have been implemented and pursued in order to provide sufficient capacity to meet the air traffic demand. First of all, EUROCONTROL’s Central Flow Management Unit (CFMU) has made a big contribution by enhancing the flow of air traffic throughout the European continent.3 The CFMU monitors capacity variations, delays, conflicts and unused air traffic control slots on an ongoing basis. Based on the outcome of this comparison, air traffic control slots are allocated, updated and (if applicable) re-routings are offered to aircraft operators in order to avoid overload of particular air navigation sectors as well as unnecessary flight delays. By optimising the use of the available airspace capacity and by offering alternatives to aircraft operators the CFMU safeguards the smooth flow of traffic throughout European airspace.

1 EUROCONTROL, Performance Review Commission: Performance Review Report: An Assessment of Air Traffic Management in Europe during the Calendar Year 2005 (April 2006), at 5. EUROCONTROL is an international organisation which has as objective the development of a seamless pan-European air traffic management system. For additional information on the member states of EUROCONTROL and the organisation’s institutional structure, see Ch. 3.3.4. The Performance Review Commission is one of the advisory bodies within the institutional structure of EUROCONTROL. 2 EUROCONTROL, Long-Term Forecast of Flights 2004-2025 (December 2004), at 3. 3 The CFMU is an operational unit of EUROCONTROL and became operational in 1996. It matches flight-plans of aircraft operators with the available air navigation service capacity. For additional information, see EUROCONTROL, Central Flow Management Unit: Making Optimum Use of Europe’s Airspace (2001). See also EUROCONTROL, CFMU Operations: Executive Summary - Edition 2002 (2002) and EUROCONTROL, Basic CFMU Handbook: General & CFMU Systems - Edition 8 (2002).

12 Introduction

Another newly emerging technology that has been used to enlarge the available capacity of airspace to the airspace users is the implementation of Reduced Vertical Separation Minima (RVSM) in forty-one states on the European continent as of January 24, 2002. Aircraft operate along pre-defined air traffic corridors where ground-based air traffic control ensures a safe separation of aircraft. The RVSM makes it possible to reduce the vertical separation between aircraft and six additional air traffic corridors were introduced which allows more aircraft to fly in the same volume of airspace. The total volume of air traffic that can ultimately fly through a single corridor is still limited and there remain crossings of particular corridors. This continues to put a heavy burden on the ground-based controlling system that have to separate aircraft at such crossings. The introduction of a satellite based Communications, Navigation and Surveillance/Air Traffic Management (CNS/ATM) system could break through this traditional pattern. By enhancing onboard instruments and by facilitating an interchange with satellite systems aircraft could eventually operate in an area of airborne separation systems rather then having to rely on the traditional ground-based controlling systems and fixed airspace routings. In this case, aircraft would no longer have to fly along the pre-defined routings, which would boost the available airspace capacity as aircraft could use all remaining airspace. This system presupposes a redistribution of tasks between traditional ground-based and airborne traffic systems in the aircraft. It would enable the aircraft operator to define the most efficient routing for their aircraft, rather than being bound to pre-defined routings.4

Beside the introduction of new technology, the traditional organisation of airspace blocks should also been taken into account. A revision of the airspace blocks could be a way to increase available airspace capacity. One of the achievements on the European continent has been the launch of Flexible Use of Airspace (FUA) where airspace is no longer designated for exclusive military- or civil purpose but considered as a single continuum to be used flexibly on a day-to-day basis. Airspace segregation, for example military training in a particular portion of airspace, is temporary and based on real use by the military for a specified period. Outside the time intervals used by the military, the airspace it can be used for civil purposes, which boost airspace capacity. The flexible use of airspace, CFMU, RVSM or CNS/ATM are only partial solutions to the problem in Europe. The main obstacle is the overall organisation of controlled airspace. The national air navigation service providers traditionally offer services in the airspace over the territory of the state where they are based and restrict their air navigation service provision to the airspace boundaries that coincide with the territorial boundaries of the state. Based on EUROCONTROL’s statistical reference of 2006 there were no less than 69 area control centres providing air traffic control to aircraft in the upper airspace.5 En-route air navigation inefficiencies alone are estimated to cost airspace users between Euro 880 million and Euro 1.4 billion per annum. The main component of the cost of fragmentation is that many national air navigation control centres operate below their optimum economic size. Other major reasons for the cost of fragmentation are the multiplication of ATM systems (piecemeal procurement, sub-optimal scale in maintenance) and duplication of associated

4 Within the United States of America this concept is commonly referred to as free flight whereas in Europe the concept is referred to as free routing. Although in principle they both refer to CNS/ATM, the difference is that in European airspace the aircraft will remain subject to clearances by air navigation service providers whereas this is not the case in the free flight environment developed in the United States of America. For additional information, see F.P. Schubert, ‘Pilots or Controllers: Who’s liable in the free flight environment’, 2002 (February) Avionics Magazine. See also J. Terlouw, ‘Air Traffic Control from the Cockpit’, 2003 (September) CANSO News. 5 EUROCONTROL, Report commissioned by the Performance Review Commission: The Impact of Fragmentation in European ATM/CNS (April 2006), at 28.

Chapter 1 13

support (training, administration and research and development).6 There are national initiatives to mitigate the adverse impact of fragmentation costs by way of the corporatisation and privatisation of national air navigation service providers. However, they tend to limit themselves to projects within a single air navigation service provider and do not focus on the efficient flow and routing of aircraft beyond the national airspace.7 Under the umbrella of the Single European Sky, the European Community tries to break through the current organisation of air navigation services. The main objectives of the Single European Sky initiative are firstly to improve safety; secondly overall efficiency; closely related to the latter is the third objective; optimise airspace capacity, and fourthly to minimise air traffic delays. The last objective of the Single European Sky is to establish a harmonised regulatory framework. This is of a different nature to the preceding objectives and should be considered as an enabler of the first four objectives.8 In terms of the aforementioned first objective, the enhancement of safety, the aim is to improve the levels of safety so that the risk per flight, i.e. the accidents and risk-bearing incidents attributed to ATM, decrease, whereas the volume of air traffic increases. With respect to the second objective, efficiency, this should be considered as a twofold objective. The first goal is to improve cost-effectiveness by reducing the unit costs of the air navigation service providers. Cost-inefficiencies arise from low productivity of the systems and high support costs, mainly due to the already previously mentioned fragmentation of the air navigation systems, duplication of infrastructure and small-scale facilities preventing full exploitation of scale effects. A reduction in unit costs will have an impact on the operating costs of the airline industry that are picking up the bill for the provision of air navigation services. At the same time, the objective efficiency has a second goal as this objective also aims to improve the flight-efficiency of the airline industry. The improvement of flight-routing will lower flight-times and increase the airline’s operating efficiency in terms of connection times but also lower its operating costs as there will be a reduction in fuel burn. Consequently, the reduction in fuel burnt and emissions will have an environmental impact. Although major improvements have already been made in respect of the third and fourth objectives, this being the optimisation of airspace capacity and reducing air traffic delays, the expected growth of general air traffic and the expected increased demand for air navigation services by very light jets makes the capacity and demand balance particularly fragile.9 One of the cornerstones of the Single European Sky is the establishment of Functional Airspace Blocks (FABs) which envisages that there are ultimately blocks of controlled airspace that are defined irrespective of the underlying national state boundaries. Within such FABs, the provision of air navigation services should no longer be exclusively the domain of air navigation service providers that are based within the territory of that state, but it should be allowed to have air navigation service providers that have their principal place of operation in the territory of another state.10 This kind of provision of air navigation services is commonly referred to as the cross-border provision of air navigation services. In 2005, EUROCONTROL and the European Community launched the Single European Sky ATM Research Programme (SESAR) that covers civil- and military aviation players, legislators, industry operators and users, both ground and airborne. The parties will define, commit to and ultimately implement a pan-European program that eliminates the so-far

6 Ibid., at 55-56. 7 See Ch. 5.3. 8 EUROCONTROL, Performance Review Commission: Evaluation of the Impact of the Single European Sky Initiative on ATM Performance (December 2006), at 7-8. 9 Ibid., at 15-16 and 24-27. 10 For additional information on the requirements that should be met under the Single European Sky Regulations to for air navigation service providers, including the requirement of principal place of operation, see Ch. 5.4.2.

14 Introduction

fragmented approach to air navigation services and supports the Single European Sky legislation. Within this context, the parties focus on the transformation of the overall European air navigation system by synchronising plans and actions of the different partners and resources. The first part of SESAR is a definition phase. By early 2008, there should be a European ATM Master Plan based on future aviation requirements identifying the actions and needs to achieve the objectives. This will be followed by a development phase (2008-2013) which covers development, validation work and preparation of regulatory measures to implement the master plan. Finally, there is the deployment phase (2014-2020). In this phase, there should be management of the changes in the European ATM, which will result in an optimal outcome.11

Notwithstanding the technological improvements and organisational developments, the European continent has also been witnessing major aircraft collisions that were interrelated with the provision of air navigation services. This study is exclusively focusing on damage resulting from air navigation service provision. Accidents or incidents connected with contributory negligence between pilots and air navigation service providers, such as in the Tenerife disaster of 27 March 1977 where in dense fog two Boeing 747 aircraft of Pan American World Airways and KLM Royal Dutch Airlines collided and where communication misunderstandings between the air traffic controller and the pilots of the KLM aircraft played an important role, will not be discussed. The first accident that solely relates to the provision of air navigation services involves the collision of a Spanish chartered Coronado 990 aircraft and a DC-9 aircraft from Iberia. On 5 March 1973 amidst a strike by the civil air traffic controllers in France the aircraft collided in mid-air near the French city of Nantes. The pilot of the Coronado was able to land the damaged aircraft, but the DC9 exploded, killing all sixty-eight people on board. The French air force, that had been providing air navigation services during the strike, denied that there was a link between the accident and the strike.12 This mid-air collision has been considered the first European mid-air collision caused by air navigation services.13 Three years later, on 10 September 1976, there was another mid-air collision of two aircraft in the airspace over the former Republic of Yugoslavia. The accident occurred near the small town of Vrbovec, between a Trident aircraft of British Airways and a DC9 operated by Inex Adria. All crew and passengers, one hundred and seventy-six people, were killed. As the accident occurred whilst the aircraft were under air traffic control from the Zagreb-based air navigation service provider, the accident is commonly referred to as the Zagreb mid-air collision.14 In the evening from 1-2 July 2002, there was a mid-air collision in the airspace over southern Germany. In contrast to the previous mid-air collisions, this accident involved cross-border provision of air navigation services as the aircraft, whilst flying through German airspace, had been under the air traffic control of a Swiss based air navigation service provider. The merits of the accident shall be separately discussed in Chapter 1.2. On other occasions, mid-air collisions have been avoided. For example on 18 February 2004, two jet-aircraft that were subject to air traffic control were on a collision course near the French city, Rheims. A collision was avoided by the swift response of the crew of Swiss International Airlines and KLM Royal Dutch Airlines. The pilots took evasive action based on their on-board Traffic alert and Collision Avoidance Systems (TCAS). If both aircraft are fitted with the TCAS system and the TCAS detects that the aircraft are on a potential collision

11 EUROCONTROL, SESAR: Single European Sky ATM Research (February 2006). 12 ‘1973: Mid-Air Collision kills 68’, BBC News on the Web: On this day 5 March 1973. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday> (Visited 1 May 2007). 13 P. Domogala, ‘The Zagreb Collision Revisited’, (2001) 40 The Controller 26. 14 For additional information, see P. Marn, Comparative Liability of Air Traffic Services, (unpublished), thesis of 15 October 1980 submitted to the Institute of Air and Space Law of McGill University, Montreal.

Chapter 1 15

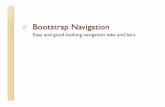

course, the computer system on the aircraft will ultimately advise the pilot of one aircraft to descend whereas the system on board the other aircraft will at the same time advise its pilot to climb. The Swiss aircraft and KLM aircraft came within 15 and 35 seconds of colliding.15 The range of technological and organisational improvements and the mid-air collision tragedies serve as a grim introduction to this study on cross-border provision of air navigation services. After revisiting the peculiarities concerning the cross-border provision of air navigation services surrounding the mid-air collision near Überlingen and explaining why this tragic collision is of importance for this study (1.2) the objectives and research questions of this study will be specified (1.3) which will be followed by the division of the Chapters (1.4). 1.2 The mid-air collision near Überlingen (Lake Constance) The merits of the case surrounding the mid-air collision near Überlingen (Lake Constance) and the court ruling by the German District Court are important with respect to the leitmotiv of this study, which focuses on the cross-border provision of air navigation services whilst safeguarding transparent lines of responsibility and liability. This is because the opinion of the District Court can be mirrored in similar situations where states allow cross-border provision of air navigation services in the airspace over their territory by an air navigation service provider that is based in and subject to the supervision of the authorities of another state. On the evening of 1 July 2002, two jet aircraft collided in mid-air at an altitude of 34.890 feet (around 10.600 meters) in the airspace over southern Germany. The accident occurred north of the German city Überlingen, near Lake Constance, and involved a Boeing 757 freighter of DHL International Ltd., on its way from Bergamo, Italy, to Brussels, Belgium, and a Russian charter flight, a Tupolev TU154, operated by Bashkirian Airlines, which was heading from Moscow, Russia, to Barcelona, Spain. The aircraft were flying at the same altitude and, as illustrated in Figure 1.2 below, approach and collided at a 90-degree angle.

Figure 1.2 Collision of the Boeing 757 and the Tupolev TU154.16 Based on bilateral arrangements between Switzerland and Germany, the Swiss based air navigation service provider, Skyguide, was the provider of air navigation services in this portion of airspace over the South-German territory. Therefore, a Swiss-based air navigation services provider was in charge of the provision of air navigation services to the aircraft involved. Whilst monitoring the two en-route aircraft in German airspace, the air traffic controller was at the same time also monitoring a delayed Airbus aircraft (“Airbus”) that was approaching Friedrichshafen airport.

15 ‘Incident in French airspace’, Press Release by Swiss International Airlines of 18 February 2004. 16 This figure has been copied from the Bundesstelle für Flugunfalluntersuchung [German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation], Investigation Report on the Accident (near) Überlingen/ Lake of Constance/ Germany on 1 July 2002 (AX001-1-2/02) of May 2004, at 72.

16 Introduction

The air traffic controller instructed the Tupolev to descend to 350.000 feet and continued his work by concentrating on the Airbus flight operations. The Boeing and Tupolev were both equipped with airborne Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance Systems (TCAS) and at the same time that the air traffic controller was monitoring the flight operations of the Airbus, the airborne Traffic alert and Collision Avoidance Systems (TCAS) alerted the crew of the Boeing and the Tupolev that they were flying on intersecting flight paths. The TCAS instructed the crew of the Tupolev to climb, which was contrary to the instructions of the air traffic controller and, at the same time, the TCAS instructed the DHL aircraft to descend. Because the Airbus’s call to the air traffic controller overlapped with the TCAS report by the Boeing (its crew reporting that it was going to descend) the air traffic controller did not receive this message. Furthermore, the controller was firm in his belief that the ‘descend’- instruction issued to the Tupolev was responded to in time and therefore had left the aircraft unattended, concentrating on the Airbus operations.17 The Tupolev was confronted with conflicting information and followed the air traffic controller instruction to descend, whereas its TCAS system had advised it to climb. The air traffic controller had not realised that the Boeing had already started to descend and gave another instruction to the Tupolev to expedite descent. The latter instruction was given by the air traffic controller, as the crew of the Tupolev had not verbally replied to the first air traffic control instruction.18 On the Russian cockpit voice recorder, the investigators were able to destillate that the co-pilot pointed out the conflict between the TCAS warnings and the instructions of the Skyguide staff. The TCAS system subsequently advised the Tupolev to increase climb, increase climb but five seconds after this message it came to a collision, albeit that at the very last moment the Tupolev crew noticed the recognisable Boeing and abruptly tried to in vain to initiate a climb. Because of automated systems air traffic controllers in Germany had noted the collision course of the aircraft and have tried to notify their Swiss colleagues.19 All 71 crewmembers and passengers of both aircraft, of which 49 were children, were killed. What made the accident even more dreadful was the murder of the Swiss air traffic controller who was on duty on the night of the mid-air collision. He was stabbed to death in 2004 by a Russian relative whose wife, son and daughter had been killed in the aircraft crash.20 Skyguide accepted full responsibility for the errors made within its organisation and took immediate precautionary safety measures.21 Furthermore, at the request of Skyguide and together with the governments of Germany and Switzerland, Skyguide created a compensation fund for the financial relief of the bereaved.22 Payments would be made for loss of income, including additional compensation, on the assumption and in accordance with standards that would have been applied if the relatives had been based in Switzerland bearing

17 Ibid., at 85. 18 Ibid., at 70-71. 19 Ibid., at 44. 20 ‘Swiss Confirm Russian Father Held’, BBC News on 1 March 2004. < http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/3522105.stm> (Visited 3 May 2007). 21 ‘Skyguide Apologizes to the victims’ families’, Press Release by Skyguide of 19 May 2004. 22 Skyguide, Annual Report (2003), at 15.

Chapter 1 17

a Swiss nationality.23 There are reports that the compensation fund has paid out one hundred and fifty thousand US dollars per deceased.24

The Russian based aircraft operator, Bashkirian Airlines brought a claim against the Federal Republic of Germany and the German District Court of Konstanz released its opinion in July 2006.25 According to Bashkirian Airlines, the German state should indemnify the company for damage to its aircraft and indemnify the company for damage claims against the airline by third parties, including but not limited to those persons legally representing the estate of the passengers and crew on board the Tupolev, claims from DHL International Ltd. for the loss of the Boeing freighter aircraft and, last but not least, claims that could be brought against the airline by Honeywell Ltd.26 The District Court had to assess whether the Federal Republic of Germany was liable for these damages. This, despite the fact that the air navigation service provider was a Swiss-based entity operating under the supervision of the Swiss authorities. The merits of the case are therefore closely connected to the leitmotiv of this study: how to pursue cross-border provision of air navigation services whilst safeguarding transparent lines of responsibility and liability? First, the District Court had to decide what law should be applied and what was the competent forum to deal with the case. As the accident had occurred in German airspace, the District Court held that, in terms of applicable law and competent forum, the case had to be decided in a German court and would be subject to the national laws of Germany.27 Next, the District Court had to judge whether the German state was liable for damages that had arisen from the mid-air collision. For this analysis, the District Court considered the national laws of Germany and the available bilateral cross-border arrangements between Germany and Switzerland. Because of German law, the court argued that there was liability for the German state as far as it concerns acts of an agent performing an official function on its behalf. The performance of

23 ‘Flugunfall vom 1 Juli 2002 bei Überlingen’, Presseerklährung von Dr. Alexander von Ziegler, Vertreter des Entschädigungspools (gebildet durch die Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, die Bundesrepublik Deutschland und Skyguide) [Aircraft accident of 1 July 2002 near Ueberlingen, Press Release by PD Dr. Alexander von Ziegler acting as representative of the compensation fund (This fund was created by Switzerland, Germany and Skyguide)]. 24 ‘Überlingen, Weiter Streit um Schadenersatz, Zwei Jahre nach der Flugzeugkatastrophe’ [Überlingen, Additional fights over compensation: Two years after the Aircraft catastrophe], Stuttgarter Zeitung On-line of 1 July 2004. <http://www.stuttgarter-zeitung.de>. ‘Skyguide erzielt Teileinigung, Rund 150.000 Dollar Schadenersatz pro Opfer’ [Skyguide reaches agreement on liability division around 150.000 US Dollars per victim], Neue Zürcher Zeitung AG of 30 June 2004. <http://www.nzz.ch>. 25 Bashkirian Airlines v. Bundesrepublik Deutschland, (2006) with the District Court of Konstanz (Landgericht Konstanz 4. Zivilkammer) under case number 4 O 234/05 H. 26 Ibid., at 10-12. The manufacturers Thales and Honeywell have manufactured TCAS systems on board the aircraft. Damage claims were brought against Thales and Honeywell in the United States. In Faat v. Honeywell Int’l, (2005) WL 2475701 (D.N.J. Oct. 5, 2005) the District Court of New Jersey dismissed the claim against Honeywell on the basis of forum non conveniens, subject to the following conditions: 1) Plaintiffs were ordered to refile their claims in the Court of First Instance in Barcelona (Spain); 2) All defendants must submit voluntarily to the Court of First Instance in Barcelona and to furnish the Plaintiff’s counsel with the details of their process agent; 3) All defendants agreed voluntarily to waive any statute of limitations or personal jurisdiction defences in Spain; 4) All defendants agreed to satisfy any final judgement rendered against them by the court in Spain; and 5) All defendants agreed to be bound by their responses to discovery requests which had already been serviced on them in the New Jersey litigation. If the defendants materially breached any of these conditions, plaintiffs would be permitted to refile their actions before the District Court in New Jersey. 27 See Bashkirian Airlines v. Bundesrepublik Deutschland (case number 4 O 234/05 H), supra note 25, at 16-18. The German court declares itself competent to deal with the matter and holds that the material laws are those of Germany based on lex loci delicti.

18 Introduction

air navigation services in German airspace is deemed an official (public) task and liability claims for air navigation services are channelled to the German state.28 Whereas according to the national law of Germany air navigation services in German airspace are to be exclusively provided by the German air navigation service provider DFS, in reality these services were provided by the Swiss-based air navigation service provider. According to the District Court, the fact that services were being provided by Skyguide did not alter the nature of the services being offered for which, in case of failure, due to German law triggers the liability of the German state. In the interpretation by the court of German laws, with respect to the performance of its services, the Swiss based provider should be considered as the agent performing the air navigation services on behalf of the German state.29 Therefore, the German state because of its national law is the actor bearing liability for the damages arising from the accident. The District Court also examined the bilateral arrangements that were concluded between Germany and Switzerland for the sake of cross-border provision of air navigation services. The court, whilst examining a treaty (which had not been signed) and a Letter of Agreement that had been concluded at the level of the German and Swiss air navigation service providers, came to the conclusion that the states had not concluded a treaty.30 Notwithstanding the non-existence of a bilateral agreement, the District Court continued by elaborating on the fact that treaties only have a binding effect between states and that the content hereof has no binding effect on the individuals of a state. Had the parties agreed on a provision dealing with liability in a treaty and had such arrangement been incorporated into the national laws of Germany, the outcome could have been different.31 The court ruled in its partial judgement that Germany has to indemnify Bashkirian Airlines for third-party damage claims. The court has yet to rule on the other aspect of the claim lodged by the Russian carrier, which deals with the extent of damages to be awarded by the German state to

28 For further details on the organisation of air navigation services in Germany, see Ch. 5.3.4. 29 See Bashkirian Airlines v. Bundesrepublik Deutschland (case number 4 O 234/05 H), supra note 25, at 20-21. 30 Ibid., at 48-52. According to the treaty (not signed) the German state would be liable for errors made by the Swiss air navigation service provider in German airspace on the same basis as it would be liable for its own air navigation service provider. However, the District Court held that the treaty had no binding effect and the Letters of Agreement did not constitute a treaty either. 31 Ibid., at 57-58: Quote “b) Die Haftung der Beklagten nach Art. 34 GG, § 839 BGB kann im Übrigen nur durch Gesetz aufgehoben oder eingeschränkt werden (Papier in Maunz/Dürig, Art. 34 Rn 237), was auch für die subsidiäre Ausfallhaftung (§ 839 Abs. 1 S. 2 BGB) gilt (Papier a.a.O., Rn 240). Daraus folgt: Die LoA könnten selbst dann nicht die Haftung der Beklagten für das Flugzeugunglück vom 1.Juli 2002 in Frage stellen, wenn die LoA als ein wirksames Verwaltungsabkommen nach Art. 59 Abs. 2 Satz 2 GG zu bewerten wären. Verwaltungsrechtliche Vereinbarungen zwischen Hoheitsträgern entfalten Rechtswirkungen nämlich nur zwischen diesen, weil sie Ausfluss der Verwaltungs- und Organisationshoheit sind und deshalb nur exekutiv wirken (Papier a.a.O., Art. 34 Rn 283). Gegenüber Entschädigungsansprüchen betroffener Staatsbürger, wobei § 839 BGB Ausländer in seinen Schutzbereich einbezieht, haben völkerrechtliche Verträge nach Art. 59 Abs. 2 Satz 2 GG infolgedessen nur dann rechtliche Relevanz, wenn diese Vereinbarungen durch Gesetz als innerstaatliches Recht umgesetzt werden (P. Kirchhoff in Handbuch des Staatsrechts, Band III, § 59 Rn 155). Völkerrechtliche Verträge werden auch nicht allein durch den völkerrechtlichen Grundsatz der Vertragstreue in Verbindung mit Art. 25 GG zu innerstaatlichem Recht (Herdegen in Maunz/Dürig, Art. 25 Rn 8 und 9). Man kann die Rechtslage auch von der These der Beklagten (Bundesrepublik Deutschland) ausgehend betrachten und gelangt zum selben Ergebnis: Folgt man ihrer Meinung, mit den LoA seien Hoheitsrechte der Bundesrepublik auf die Schweiz übertragen und damit die eigene haftungsrechtliche Verantwortung übergegangen oder eingeschränkt worden, so wären die LoA ihrem materiellen Inhalt nach nicht nur Verwaltungsabkommen über technische Regelungen der Flugaufsicht, sondern Bundesrecht betreffende völkerrechtliche Verträge nach Art. 59 Abs. 2 S. 1 GG, die zu ihrer Wirksamkeit der innerstaatlichen Transformation durch ein förmliches Vollzugsgesetz bedurft hätten (Maunz in Maunz/Dürig, Art. 59 Rn 37).“ End of quote.

Chapter 1 19

Bashkirian Airlines.32 Germany has appealed the judgement and the partial court ruling of the District Court is not the final decision. Furthermore, beside the liability for damages, the Swiss authorities commenced criminal investigations and charged eight air traffic controllers on charges of manslaughter and negligence.33 As reflected in the opinion of the District Court, the German state is liable for damages. German national law does not allow the state to redirect the claim from Bashkirian Airlines to the Swiss-based air navigation service provider. In addition, the lack of a bilateral agreement between Germany and Switzerland prevents Germany from seeking recourse to the Swiss state to recoup any damages that it has paid towards parties like Bashkirian Airlines. It would of course be advisable for Germany to enter into a solid legal bilateral agreement with Switzerland to remedy any such discussions for the future. At the same time, the outcome of this court case also casts a shadow over the wide-scale cross-border service provision of air navigation services in general. Eventually, this could result in a slow-down of wide-scale implementation of cross-border service provision altogether. After all, on the basis of the German ruling, states may be reluctant to allow air navigation service providers that, similar to Skyguide, are based in the territory of another state and rely on the host state’s supervision to provide air navigation services in their airspace. 1.3 Objective and research questions As illustrated in Chapter 1.1, there is a continuous increase in the flow of air traffic traversing the airspace of the European Community triggering a greater demand of air navigation services. However, there are also other problem areas in the world that encounter the difficulties of matching airspace demand of the airspace users (airlines) with the availability of suitable and sufficient air navigation services such as for example in the United States of America. The Air Traffic Organization of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is guiding about 50,000 aircraft every day and the airspace in the north-eastern corridor of the United States with major international airports is one of the busiest in the world. Through airspace redesign, the FAA has increased efficiency and reliability of air navigation services in that particular aviation area. Another example of dense air traffic is the Asia-Pacific region that has seen a strong increase in commercial flights. The states in that region will in due course also have to revisit the traditional way in which their national air navigation service providers are offering air navigation services to airspace users.

32 See Bashkirian Airlines v. Bundesrepublik Deutschland, (2006) (case number 4 O 234/05 H)¸ supra note 25, at 62. The court-ruling is partial judgement (Grund- und Teilurteil). Although the German state should indemnify the Russian airline from claims of third parties, the District Court did not decide on the extent of the damage amounts claimed by the airline because of difficult questions of Russian law that had to be answered. Bashkirian Airlines was not the legal owner of the aircraft which triggered the question as to wheter or not damages can still be awarded due to the fact that the airline suffers economic loss from not being able to make use of the aircraft. The extent of the damages to be awarded shall be decided in the final court ruling of the court. 33 To the knowledge of the author the Federal Government of Germany has appealed the judgement of the District Court. See also, S. Hobe, ‘Current Liability Problems of German Air Traffic Services: Überlingen and Other More Recent Developments’, in EUROCONTROL (ed.), proceedings of the workshop: Responsibility and Liability in ATM – moving targets in a changing European Airspace, organised by EUROCONTROL in 2006, at 5. Also, P. Nikolai Ehlers, ‘Case note: Lake Constance Mid-Air Collision: Bashkirian Airlines v. Federal Republic of Germany’, (2006) 32 Air Law 75, at 79. The eight air traffic controllers faced with charges of manslaughter and negligence were all employed by Skyguide at the time of the accident and face jail sentences of up to fifteen months if found guilty. See, ‘Swiss charged over 2002 air crash’, BBC News on the Web of 7 August 2006. < http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/5253696.stm> (Visited 19 May 2007). See also ‘Swiss go on trial over air crash’, BBC News on the Web of 15 May 2007. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/6656487.stm> (Visited19 May 2007).

20 Introduction The focus of this study is on the European Community where relatively small portions of upper airspace are subject to the provision of air navigation services by multiple air navigation service providers. Contrary to, for example, the United States of America where large air navigation service corridors can be redefined within the airspace of a single state, for the European Community counts that realignment of air navigation service corridors within the airspace of a single state is only possible up to a very limited extent. In order to enhance the efficient flow of air traffic and free up available airspace in the European Community for the purposes of air navigation services, this requires another approach. One of the solutions is the provision of cross-border air navigation services as envisioned under the Single European Sky regulations. This implies cross-border provision of air navigation services by air navigation service providers in blocks of airspace that are defined irrespective of the territorial boundaries of the underlying states. Those air navigation services could even be provided by air navigation service providers, or groups of air navigation service providers, that are based in the territory of a state, other than the state in whose airspace those services are being provided. The mid-air collision near Überlingen illustrates the need to reflect and reconsider the way cross-border provision of air navigation services is being formalised. After all, the opinion of the German District Court illustrates that claims for damages are not per se directed against the air navigation service provider, but depending on the preference of the plaintiffs and subject to the applicable national law, can also be directed against the state in whose airspace the air navigation services are being provided. Besides the question as to where to file the claim, there is also the question as to what is the applicable law and competent forum according to which the liability claims should be dealt with. Depending on the circumstances of the damage inflicted because of a mid-air collision damage claims can be filed against the operator and the owner of the aircraft, airline personnel, passengers on board the aircraft (or in case of death those persons legally representing their estate), owners of cargo which was on board the aircraft, as well as by third parties suffering damage on the ground. At the same time, due to the nature of cross-border service provision where the air navigation service provider has his principal place of operation in a state other than the state in whose airspace the services are being provided, damage may be inflicted on the state in whose airspace the cross-border services are being provided and this state may also wish to claim damages. This study will focus on three main aspects dealing with the provision of cross-border air navigation services in European airspace, and more particularly the European Community. First, the international- and European legal framework dealing with air navigation services will be considered. Secondly, the question of state responsibility for the provision of air navigation services will be taken into account and, last but not least, attention is paid to the question of liability for damages inflicted by air navigation service providers. Due to the ongoing flow of position papers, documents and legal articles in the field of air navigation services, the author has made the decision to base its findings, paradigm shifts on the available resources on this topic up to 1 June 2007. For the sake of clarity, this study does not focus on the complications faced by certain air navigation service providers that are offering both civil- and military air navigation services. In The Netherlands there is a separate provision of military- and civil air navigation services. The military has its own air navigation service system that is in charge of policing national airspace. However in Germany and Switzerland the air navigation service providers are providing air navigation services both for civil- and military airspace users. The military policing of German and Swiss airspace are therefore embedded in the organisational structures of both air navigation service providers. This complicates matters if these organisations wish to expand their provision of air navigation services beyond their national airspace. After all, the state in whose airspace services are being offered may, although not being reluctant against the civil expansion of the foreign air navigation service provider in its airspace or collaboration efforts undertaken between the civil aspects of air navigation

Chapter 1 21 services, not look forward to have foreign military control and involvement in its airspace for reasons of national security. Beside brief reference to civil- and military arrangements as far as flexible use of airspace is concerned in Chapter 1.1 this study will not further elucidate this matter but will concentrate on the civil aspects related to air navigation services and will examine the international- and national legal framework for purposes of cross-border provision of air navigation services for civil aviation. In relation to the first part of this study, the international- and European legal framework dealing with air navigation services, the provision of air navigation services states have always been subject to the rulemaking- and, to a certain extent, enforcement competencies of international organisations. Besides the global international legal framework for air navigation services laid out in the Chicago Convention and the role of ICAO, there are at least three international bodies in the European Community that, up to a certain extent, have rulemaking- and enforcement competencies. These are the European Civil Aviation Conference (ECAC), the European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation (EUROCONTROL) and, last but not least, the European Community with its agency the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). To what extent have these international organisations received rulemaking- and enforcement competencies in the field of air navigation services? Within this context, this study will look closely at the interrelationship between EUROCONTROL and the European Community. Despite the different institutional structures of the two international organisations, each having its own regulatory- and enforcement mechanisms, the European Community has aceeded to the revised convention of EUROCONTROL and therefore became bound to its law-making and enforcement competencies. At the same time, the European Community incorporates rules established through EUROCONTROL rulemaking procedures in its own legal order. What is the impact of such accession on the rulemaking- and enforcement competencies of the international organisations as far as this concerns the operational efficiency of cross-border provision of air navigation services? Does the legal order of the European Community prevail over the legal order of EUROCONTROL? The second part of this study concentrates on state responsibility and, more specifically, how to establish clear lines of state responsibility in the context of cross-border provision of air navigation services. States are encouraged through the aforementioned developments and to enhance efficiency by facilitating cross-border provision of air navigation services and allow air navigation service providers to offer air navigation services in their airspace whilst the providers have their principal place of operation outside their territory (or vice versa). Meanwhile states have entered into various forms of bilateral- and multilateral arrangements to facilitate limited cross-border service provision in their airspace. Have they considered the issue of state responsibility in the arrangements they concluded? Is it possible to relieve a state from state responsibility if such state allows the provision of air navigation services in their airspace by a foreign air navigation service provider that has his principal place of operation in another state in the event the air navigation service provider fails to meet international obligations imposed on the state under the aforementioned international- or European legal framework? The last part of this study concentrates on liability for damages arising out of the provision of air navigation services. Whereas traditionally air navigation service provision was performed by air navigation service providers that formed part of the governmental structure, such providers have been transformed into corporatised and privatised entities outside the governmental structure. However, have states also considered imposing a clear liability regime on the air navigation service provider if things go wrong and, furthermore, have they considered the issue of liability if their air navigation service providers engage in cross-border service provision activities? In order to determine whether states have laid down a clear liability framework under their national law in terms of the liable actor, the laws to be applied and the competent forum, an analysis must be made of the national laws of states. Due to the

22 Introduction rearrangement of national air navigation service provision envisioned by the European Community through its Single European Sky regulatory framework, an analysis of these regulations must also be made. Beside the issue of national laws, how should questions of inter-state liability be dealt with? For the benefit of transparent lines of liability, should states enact specific inter-state liability regimes that at the same time take into account the issue of damages suffered by third parties on the ground? Moreover, is it useful for aircraft operators to engage in a contractual-based liability framework with the air navigation service providers for the benefit of transparent lines of liability in case of cross-border provision of air navigation services? An attempt will be made to answer these questions in accordance with the structure that is explained in the following Chapter 1.4. 1.4 Division of chapters Chapter 2 will start by giving a brief overview of the principles of public international law such as state, territory, sovereignty and jurisdiction, after which the international legal framework of the Chicago Convention will be set out. ICAO, through its rulemaking- and enforcement powers, has played an important role for the development of air navigation services. The organisation has implemented a harmonised framework of air navigation services and imposes obligations to which states are bound when air navigation services are provided in their airspace. Chapter 3 will analyse and evaluate the European legal framework for air navigation services, which is imposed by international bodies such as ECAC, EUROCONTROL and the European Community. On the basis of the analysis and evaluation of the regulatory- and enforcement competencies of EUROCONTROL and the European Community, this Chapter will discuss the interrelationship between the two organisations, including EASA. Also, a number of comments and observations will be made with respect to the manner in which these international organisations could co-exist in the field of air navigation. Chapter 4 will analyse the concept of cross-border provision of air navigation services and differentiate this type of provision of air navigation services from other kinds of air navigation service provision. This Chapter will discuss extra-territorial air navigation service provision over the high seas and in airspace of undetermined sovereignty and, lastly, the provision of air navigation services in autonomous entities. This Chapter focuses on the need to establish transparent lines of responsibility when states or their air navigation service providers engage in cross-border provision of air navigation services. After setting out on what basis states bear state responsibility for the provision of air navigation services in their airspace, a number of inter-state bilateral- and multilateral cross-border arrangements will be examined. To what extend have states dealt with the rationale of state responsibility when allowing a foreign air navigation service provider of another state or an international organisation providing air navigation services in their airspace? After the above analysis, this Chapter will consider whether the international legal framework laid down by the Chicago Convention allows states to delegate state responsibility when they engage in cross-border provision activities and allow a foreign air navigation service provider (subject to the regulatory and enforcement competencies of another state) to provide air navigation services in their airspace. Can states be relieved from state responsibility for cross-border provision of air navigation services and, if so, to what extent can they give binding effect to such delegation of state responsibility against third-party states? Does such possibility exist under the Chicago Convention? Chapter 5 concentrates on the establishment of transparent lines of liability. Traditionally, air navigation service was provided by governmental agencies that could be subject to state liability. However, many air navigation service providers have been subject to a first wave of restructuring where states restructured the traditional governmental agencies into corporatised or privatised entities. In this respect, states have enacted specific national laws governing their

Chapter 1 23 air navigation service providers and several national air navigation service providers and their national laws will be analysed in this Chapter. This is followed by a review of the Single European Sky regulations as these regulations are designed to trigger a second wave of restructuring of air navigation service providers in the European Community. Next, the national laws and obligations under the Single European Sky will be revisited for the purpose of establishing transparent lines of liability in case of cross-border provision of air navigation services. Which entity is liable, what laws should be applied and what is the competent forum? After the review of the traditional liability concepts embedded in the national laws of states, the issue of cross-border provision of air navigation services is taken into account. Have states considered transparent lines of liability in their national laws when their air navigation service providers engage in cross-border provision of air navigation services? Have states concluded inter-state liability agreements that deal with damage arising from the provision of air navigation services by an air navigation service provider that has his principal place of operation in the territory of another state, but causes damage to third parties on the ground in the territory of the other state? Furthermore, should aircraft operators and air navigation service providers engage in contractual agreements establishing transparent lines of liability in case of cross-border provision of air navigation services? Last, to what extent should a legislator take up action in this respect? Triggered by the consolidation developments and the regulatory restructuring that are taking place in the European air navigation services industry, this study will restrict itself to establishing transparent lines of responsibility and liability for cross-border provision of air navigation services in the airspace of the European Community. On the basis of the findings in this study, Chapter 6 will enumerate the essential elements required for cross-border provision of air navigation services and provide a number of final recommendations and conclusions on the best way to pursue cross-border provision within the European Community. This Chapter will conclude by extrapolating the conclusions and recommendations for the benefit of cross-border provision of air navigation services beyond European airspace.

25

CHAPTER 2 The International Legal Framework 2.1 Introduction Any legislative efforts in the field of air navigation services and, more specific, cross-border provision of air navigation services, should first be approached from an international angle. After all, in an effort to create a level of international uniformity in the field of civil aviation the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) has, as an international legislator, established the international legal framework for air navigation services. For the development of such a unified framework of air navigation services, ICAO relies on rulemaking- and enforcement competencies that are embedded in the founding treaty of that international organisation, the Convention on International Civil Aviation (henceforth also cited as the Chicago Convention or Chicago).34 This Chapter discusses the rulemaking and enforcement powers of ICAO in the field of air navigation services, with special reference to the cross- border provision of air navigation services. The topics that will be dealt with in this Chapter have been divided in the following manner: first, for the purpose of understanding the principles state, territory, airspace as well as the intrusion on state sovereignty because of the voluntary restriction on the exercise of national competencies by states in favor of international organisations, attention will be paid to these fundamental principles of international law (2.2). Next, the institutional structure of ICAO will be discussed by picturing the core bodies as well as the regional air navigation regions and regional bodies including their respective interrelationships (2.3.1). The global structure of air navigation services and terminology as developed by ICAO will then be dealt with (2.3.2). This is followed by the analysis and evaluation of rulemaking competencies that have been awarded by the member states to ICAO (2.3.3). In addition, the limited enforcement competencies of ICAO will be analysed and evaluated (2.3.4). Final remarks and conclusions shall serve as an introduction to the alternative developments that are taking place in the context of the European legal framework, which will be discussed in Chapter 3 (2.4). 2.2 Principles of International (Air) Law 2.2.1 State, Territory, Airspace There are no cogent standards as to what constitutes a state, but the objective criteria as enacted in the Montevideo Convention appear to represent the qualifications that should be met.35 According to the opening article of the Montevideo Convention, the state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: it should have a permanent population, a defined territory, a government exercising government authority and, lastly, a capacity to enter into relations with other states. Shaw addresses that, despite the fact that there is no rule prescribing the minimum area of territory, in order to qualify as state, it should at least possess some portion of the earth’s surface.36 The territory of the state includes the airspace above its land, national waters and territorial sea, but the vertical limit of the airspace remains unclear. Air law has defined the term airspace, thus leaving unanswered the question as to where precisely the boundary lies in relation to outer space. The boundary has been held to be between 80 and 120 kilometres, although states, for licensing space activities, have sometimes fixed an arbitrary limit in their national laws where activities over a certain altitude (100 kilometres) are subject to particular

34 1944 Convention on International Civil Aviation, 15 UNTS 295. 35 1933 Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States, 164 LNTS 19. 36 M.N. Shaw, International Law (1997), 331.

26 The international legal framework