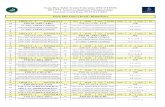

10 Art Col Dr Najib

-

Upload

leong-tuck-yee -

Category

Documents

-

view

12 -

download

0

Transcript of 10 Art Col Dr Najib

Mohamed Najib Ahmad Dawa- Batik Art in Transgression

Artist Mohamed Najib Ahmad Dawa’s journey in art is nothing short of exciting and thrilling. Not many can claim to begin life as a common struggling artist at the Central Market and Wisma Yakin at Jalan Masjid India, Kuala Lumpur before studying his way up to become the dean of USM's Centre for Art Studies. Now he assumes the helm at the National Art Gallery as the Director-General.

Equally interesting is his need to keep searching for his personal style and identity as an artist, having being born just a few years before Merdeka and lived through the formative and tumultuous years when his identity as an artist or citizen of a new nation sometimes pressed to be defined.

Just as thrilling is his taking heed of art-historian Heine-Geldern’s words with regards to identity and roots: “the past can be partly reconstructed from the present, for art proceeds from other art, contemporary forms can be traced back genetically to ancient forms.” With that, he looked into the batik motifs found in sarongs known as loccan produced in the early 1900s.

And he found that each of those sarongs is a painting by itself, containing a wealth of messages and symbols which are known only to the members of the culture. It was utterly surprising as these sarongs were common everyday clothes meant for wearing around the body. In his research, he was also surprised to come across a book in England documenting such batik cloth designs, one of which happened to come from his personal collection. From extensive research, he went on to document at least four hundred original batik motifs that have evolved in this region.

An occasion arose two years ago when he was forced to look deep into his own life. Unfortunate it may have seemed but the time taken off to fight cancer and recuperate has compelled him to seriously rethink of what he really wanted to do with his life and what he wanted to contribute to the world. He took to painting again incorporating the symbols and designs from his research, painting batik on canvas with acrylics. With clear objectives in mind, painting was now both a therapy and a means of expressions to raise the level of batik craft to profound art and to keep alive the many forgotten archetypes and symbols in our modern society.

“In this situation,” Dr Najib says, “the artwork has moved into another dimension where it is not used for “body beauty” as in the traditional context but for “visual consumption”. To the artist, the expression “visual consumption” carries the meaning of “viewing for appreciation.” But the problem arises in selecting the right motifs for the right purposes so as to function as a vehicle for messages, if not it will just merely be decoratives.

“Therefore, I have assembled all the elements found in batik and then formulated it in a way for it to function as subject matter for the painting. Elements like structures found in sarongs such as kepala kain, are a significant structure which represents the centre, or the soul of the sarong and is usually accompanied by pucuk rebung (young bamboo shoots)

motifs.”

The triangular bamboo shoots represent the male and female, who are soft and pliable at youth and strong and brave in adulthood. Pairing them side by side represents a meeting between the sexes. In conclusion, a sarong may tell the story of a person’s metamorphosis or life history!

Through his deep realisation of how rich our traditional arts are while keenly aware of how much culture has deteriorated in our everyday life, he exploited whatever motifs and designs he could and transformed them from their original medium and format to a different platform that is the gallery context. Dr Najib continues:

“Thus the use of the gallery has transformed it or transgressed it from its traditional to its contemporary context. The relationship between the words ‘transgress to contemporary’ within this context implies a break away from its traditional usage for decorating the fabric for the purpose of ‘body beauty’ (wrapping around the body) to ‘body of space’ in relation to visual arts. The qualities of the object at this stage change from the state of ‘utilitarian’ to objects of ‘contemplation’ as from ‘catwalk’ to ‘gallery space’.”